Emotional Intelligence and Personality and Implicit Aggression

Hyejoo J Lee*

Handong Global University, Korea

Submission: January 20, 2018; Published: January 29, 2018

*Corresponding author: Hyejoo J Lee, Handong Global University, Korea; Email: joanna@handong.edu

How to cite this article: Hyejoo J Lee. Emotional Intelligence and Personality and Implicit Aggression. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2018; 8(3): 555736. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2018.08.555736

Abstract

Emotional Intelligence (EI) has shown a link with various construct of personalities but previous studies presented mixed results that in some studies neuroticism showed the strongest relationship with EI while other studies did not provide any evidences of its association with EI. The present study investigates the relationship with EI using different types of personality assessment, implicit personality. Along with previous studies implicitly aggression is not correlated with self-report aggression and implicitly aggressive individuals believe they manage their emotions well while self-reported neurotic individuals do not show the relationship with EI.

Abbreviations: EI: Emotional Intelligence; CRT-A: Conditional Reasoning Test for Aggression; MEIS: Multifactor Emotional Intelligence Scale; MSCEIT: Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; TSDI: Trait Self-Description Inventory; JMs: Justification Mechanisms; TIPI: Ten- Item Personality Inventory; BFI: Big Five Inventory

Introduction

Although one single universal definition of Emotional Intelligence (EI) is still being debated over decades [1], its necessity of a modest relationship with personality is widely accepted [2,3]. One ofthe essentials of EI tests is a modest positive relationship with personality. A number of researchers explored the relationship between EI and personality, but there have been mixed results. From the most popular personality trait model, the Big Five some argued that openness to experience needs to be the strongest dimension in a relation with EI, while in Dawda and Hart's [4] study, the dimension of openness to experience had the lowest association with EI. Furthermore, some studies showed positive associations between extraversion and emotional stability, and EI [5,6]. A recent study by Joseph and Newman's [7] cascading models demonstrates that neuroticism is only a moderator: emotion perception needs to come before emotion understanding, and the emotion understanding should precede emotion regulation. Neuroticism only affects emotion regulation.

Although emotional stability has emotional construct even in its name, a concrete relationship between emotional stability and EI is still lacking. The mixed results could be due to issues with personality measures, because most of the personality measures relied on self-reports of personality [8,9]. In a field of personality research, interest in implicit motives and personality has increased and has demonstrated different predictions between implicit and explicit measures of personality [10,11]. For instance, Woike’s [12] study showed that students who tend to score high on implicit motives are more likely to remember affective experience, while those who scored high on explicit motives have a strong memory that involves self-concept. Thus, it is necessary to broaden personality measures to investigate the relationship among various facets of personality with emotional intelligence. In this present study, we will review previous studies of EI with personality; then we will introduce a new measure of implicit personality (the Conditional Reasoning Test for Aggression [CRT-A]) and present an empirical study with EI and the CRT-A.

Redundancy between EI and personality has been argued since the birth of EI, but the majority of EI researchers expect at least a modest relationship between EI and personality [13,14]. Although there is a lack of clear definition of EI, throughout this paper we adopt Mayer [15] approach, which focuses primarily on mental ability with four branches of emotions. These include the ability to perceive or identify emotions, the ability to facilitate emotions, the ability to understand emotions and the ability to regulate or manage emotions. Each of these EI branches has been expected to relate with different facets of the Big Five. From the Big Five, neuroticism seems to be closely related with EI. Adjectives that describe neuroticism are as follows: tense, moody, unstable, nervous, anxious, impulsive, depressed, vulnerable, and temperamental [16]. Since the adjectives for neuroticism are closely related to emotion-related words, it is expected to be associated with EI, especially for understanding and managing emotions.

Individuals who understand how to control their emotions will less likely to be moody and anxious. Also, people who can manage their emotions will less likely to be impulsive or vulnerable. Previous studies, however, show mixed results in predicting EI and personality, especially with neuroticism. Accumulating studies of personality have mixed evidences of EI with various measures of personality [17-27]. For instance, in Caruso, et al. [19] study, participants completed the Multifactor Emotional Intelligence Scale (MEIS) and the 16 Personality Factors which include Warmth, Reasoning, Emotional Stability, Dominance, Liveliness, Rule-Consciousness, Social Boldness, Sensitivity, Vigilance, Abstractedness, Privacy, Apprehension, Openness to Change, Self-Reliance, Perfectionism, and Tension [28]. Out of these 16 factors, only Reasoning, Sensitivity, Vigilance, and Self-Reliance showed significant correlation with an overall measure of the MEIS.

Schulte, et al. [13] argued that there is much overlap between EI and personality. They adopted NEO-Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) [16] which is a shortened version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and the MEIS, Mayer- Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Unlike Caruso, et al. [19] study showed that each facet of the Big Five was significantly correlated with EI. Individuals who are more neurotic are less likely to be emotionally intelligent. Another study that also demonstrates mixed results is Roberts et al. [24]. This study also used MEIS to explore individuals EI, and for the personality comparison, they adopted Trait Self-Description Inventory (TSDI) [29]. Roberts et al. [24] investigated various scoring systems that showed differing associations with personality. For instance, neuroticism has a significant negative relationship with each branch of EI; on the other hand, the expert scoring system did not show any significant relationships with each factor of EI in matters of perception, assimilation, understanding and managing emotions.

Another four factors of personality also presented similar evidences with neuroticism in terms of their association with two different scoring systems. Most personality factors seemed to be significantly associated with most of EI branches when scored by consensus but not based on expert scoring. Although MSCEIT is one of the widely used EI measures, it has been shown unstable in relationship with personality. EI experts expect a small too modest relationship with personality. Previous studies presented mixed results, and this could be due to using different personality tools of self-reported personality measure. Recently self-reported personalities and implicit personalities show different predictions; therefore, it is necessary to explore EI with an implicit personality measure as well.

Implicit Personality (Conditional Reasoning Test for Aggression)

Participants can fake and distort their responses to selfreported personality tests [30]. This is especially prevalent when participants or applicants need to respond to socially undesirable behavior measures (i.e. stealing, lying, and cheating). Most people are afraid of expressing their antisocial tendencies, and thus faking is one of the most prominent features of self-reported personality tests. To provide alternative and psychometrically sound measurements, James suggested a new implicit personality measurement technique-conditional reasoning [31-34]. This reasoning process is "conditional" because one's judgment regarding appropriate or acceptable actions depends on how strong a motive one has to carry out the behavior about which one is reasoning (i.e., trying to justify).

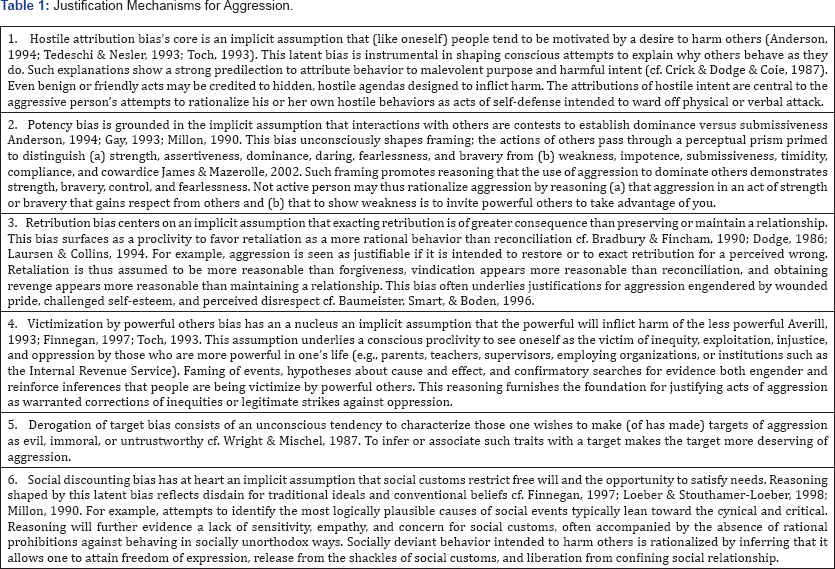

Every day, people do things based on what they believe is right or appropriate. This judgment, belief, or idea is not the same for everybody. Even in the same situation, people can make different judgments, and they act accordingly. Even if it may not seem acceptable or reasonable to others, they are ready to justify their actions. Thus, aggressive individuals and non-aggressive individuals make different decisions in the same situations, and each party has reasons for their actions which seem reasonable and rational to them. According to James [31], the reasoning biases that aggressive individuals use to make their actions appear rational and sensible are called "Justification Mechanisms (JMs)." These biases, or JMs, do not sound logical or reasonable to pro-social individuals; however, to aggressive individuals, these JMs appear sensible and rational. More interestingly, these biases are implicit, and as a result, aggressive individuals unconsciously rationalize their actions and beliefs using JMs. Six JMs are Hostile Attribution Bias, Potency Bias, Retribution Bias, Victimization by Powerful Others Bias, Derogation of Target Bias, and Social Discounting Bias. Detailed JMs are described in Table 1.

Sources: James RL, McIntyre MD, Glisson CA, Green PD, Patton TW, et al. 2005. A Conditional Reasoning Measure for Aggression. Organizational Research Methods 8: 69-99.

Interestingly enough, even though implicit and explicit measures assess the same construct of motive or personality, there tends to be no association between implicit and explicit, and it is called a dissociative hypothesis. The core of the dissociative hypothesis was proposed by McClelland, et al. [11], who suggested that a low correlation between an implicit measure and an explicit measure of the same motives indicates that the measures are tapping into different facets of motives; thus, the implicit and explicit components of motives are unrelated to each other. Mc Clelland et al. [11] primary claim of differences between implicit and explicit motives is from several decades of studies, which say that "implicit motives are based on incentives involving doing or experiencing certain things and that self-attributed motives are built around explicit social incentives or demands (p. 697]."

Thus, one can infer that implicit motives are more influenced by affective experiences and tend to be developed early in life, while explicit motives develop later in life after self-concept has been attained. Woike's [12] study supported McClelland et al. argument. In her study, participants were asked to complete TAT, which is a test assessing implicit motives to achieve, self-reported achievement motivation, and a recorded 60 consecutive days of most memorable experiences. The results showed that the implicit measure was associated with memorable experiences such as "I had a very good run this morning, "or" I did better than I expected on a test," while the explicit measure was related with more routine experiences. For instance, "I took a test," or "I wrote two papers." Contended that implicit and explicit measures demonstrated different predictions Mc Clelland et al. [11]. Implicit measures were better predicted because any experiences included affective components, while explicit measures were more associated with routine experiences.

Along with previous studies, we first of all expected no association between implicit and explicit measures of aggression in personality tests. Second, we expected implicit measures for aggression to be correlated with understanding and managing emotions. Implicitly aggressive individuals are ready to justify cognitive biases of their aggression. The biases from the JMs include affective components such as hostility, retribution, and derogation of target. Since in their cognitive system these biases are in place, they may not understand and manage their own emotions well. Third, we expect no correlation between self-reported personality and EI. In addition to aforementioned studies.

Method

Participants

One hundred and ninety-nine students (73.7% were female students, mean age = 20, SD = 1.42) participated in this study. The majority of the participants were Caucasians (89%), and 20% were majoring in social sciences including psychology, sociology, and political science. All participants received class credit.

Measure

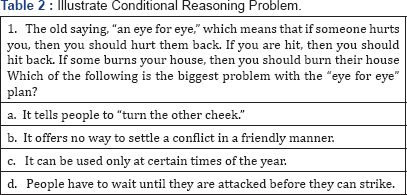

Implicit Personality Test (Conditional Reasoning Test for Aggression). The CRT-A consists of twenty-two seemingly inductive reasoning items with three bogus items to provide face validity. Each item consists of a short premise with four alternatives. Respondents are asked to read each premise and endorse one logically appealing response. In four alternatives, there are two illogical responses: one response that is seemingly logical to aggressive respondents, and one response that appears to be sensible to a pro-social personality. A sample question is presented in Table 2. In this item, the two illogical responses are alternative A and alternative C. These two alternatives cannot be inferred from the given premise, and may even be irrelevant. Respondents with at least a seventh-grade reading level clearly see that those illogical alternatives do not make sense [35].

From the remaining two alternatives, passively aggressive individuals are likely to endorse alternative D: "People have to wait until they are attacked before they can strike". According to James et al. [34], aggressive respondents favor this alternative because they have implicit retribution bias and victimization bias which says that less powerful individuals are victims of more powerful others; therefore, they are treated unequally and unjustly. Pro-social individuals will choose alternative B because they believe that people can resolve the issues through understanding. Participants who endorse a pro-social response will score +1; aggressive respondents will receive -1, and all illogical responses will score 0. Individuals who choose more than 5 illogical alternatives are dropped for further analysis. Internal consistency is not an applicable reliability index for CRT-RMS (there are two components to each item).

A Multi-Factor Emotional Intelligence Scale (MEIS)

The original measure of the MEIS [36] is a multi-factor intelligence measure which assess four areas of EI: (a) emotional identification (perception) (4 tests: Faces, Music, Designs, and Stories); (b) assimilating emotions (2 tests: Synestheisa and Feeling Biases); (c) understanding emotions (4tests: Blends, Progressions, Transitions, and Relativity); and (d) managing emotions (2 tests: Others and the Self).In the present study we only focused on understanding based on progressions and managing emotions of others and self. Responses of across 3 subtests were scored using expert scoring systems. For details of these scoring processes see Roberts et al. [24].

Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI)

The ten-item questionnaire, based on the Big Five Factor theory, assesses the dimensions of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Emotional Stability. The test asks the subjects to rate how they see themselves (Critical, Sympathetic, and Calm) at a seven-point scale where 1 means "Disagree strongly" and 7 is "Agree Strongly". There are two items for each dimension, were one is reversed, pinpointing every dimensions' extreme point (Extroversion-Introversion). Gosling, et al. [37] compared TIPI with the Big Five Inventory (BFI) and other tests measuring the Big Five, to check TIPI's usefulness. Convergent correlations were substantial, ranging from .87 to .65, all proved to be significant. The convergent correlations had a mean of .77 and exceeded the discrimination correlations, which had an absolute mean at .20, and the highest relationship were r = .36.

Results

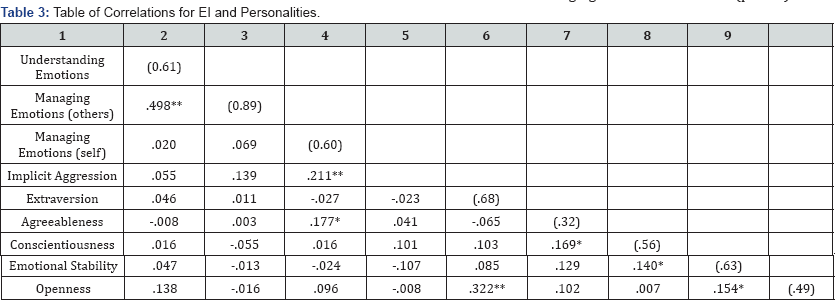

First of all, the reliabilities of the EI measures were higher than .60, .61, .89, and .61 for understanding, managing others, and managing self, respectively. On the other hand, as presented in Table 3, reliabilities of the Big Five based on the TIPI is quite low, and this may be due to a small number of items, two items for each dimension. As expected, implicit and explicit aggression (emotional stability) was not correlated, while self-reported personalities were positively correlated among themselves. Extraversion and openness to experience were highly correlated (r = .322, p < .01), as well as conscientiousness and agreeableness (r = .169, p < .05), conscientiousness and emotional stability (r = .140, p < .05), and openness to experience and extraversion (r = .154, p < .05). On the Emotional Intelligence scale, understanding emotion and management of emotion of others showed a high magnitude of correlation (r = .498, p < .01), although there was no significant association between managing self and others' emotions. More importantly, the score for implicit motives to aggression is significantly associated with a score of emotional management of self in a positive direction (r = .211, p < .01), while emotional stability showed no significant correlation with emotional management. Agreeableness showed a significant correlation with managing emotions of self .177 (p < .05).

Note: N=199, **denotes p < .01 and * p < .05.Numbers in parentheses are reliabilities.

Discussion

A moderate relationship between emotional intelligence and personality has been expected and was shown in previous articles. As the new implicit measure has been developed, the purposes of the present study were to replicate the relationship between the emotional intelligence and personality and explore the association between the implicit personality of aggression and emotional intelligence. The dissociated hypothesis was supported that there was no significant relationship between implicit and explicit personalities of aggression. Interestingly enough, there was a positive association between implicit aggression and managing one's emotions, while there was no correlation between explicitly aggressive tendencies and managing one's emotions. This needs to be investigated further. Implicitly aggressive individuals can be considered Machiavellian. Unconsciously, implicitly aggressive individuals are hostile towards others, but they are not aware of their aggressiveness.

Unlike physically or explicit aggressive individuals, passively aggressive people may be good at manipulating; they are well- controlled in their emotions or they believe they can control their emotions well. Among the self-reported Big Five traits, agreeableness was associated with managing emotions of self. Adjectives that describe agreeableness are friendly, generous, helpful, etc. and generous individuals will more likely control their emotions well. It is hard to imagine people who are friendly and generous to others to lose control of their emotions and get angry or mad at others. Much of personality research has relied on self-reported personality. If one understands his/ her personality and is willing to report honestly, then the selfreported personality test will be less problematic. However, if one is not sure how he/she acts and is less likely to report his/her negative characteristics, then the approach will be problematic. Complementary to the self-report is implicit personality measurements, which assess the unconscious level of personality through individuals’ reasoning processes. The present study utilized both self-report and implicit personality assessment to investigate their relationships with emotional intelligence and suggested interesting results. As the field of emotional intelligence is still young, more valid measures will be needed.

For the validation process, researchers in this field need to consider which personality measure, explicit or implicit; they will use to validate their new measures and need to be able to justify their actions. The present study opened a door to a new world of implicit personality and emotional intelligence. Although this study presents novel findings, it has some weaknesses. First, this study only used one unstable emotional intelligence measure. There are not many available emotional intelligence measures, and the MEIS is not well accepted by other researchers in this field due to issues with validities and reliabilities [1,24]. In the future, as more diverse emotional intelligence measures develop in their relationship with different types of personality measures, it will be interesting to explore.

References

- Cherniss C (2010) Emotional Intelligence: Toward clarification of a concept. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice 3(2): 110-126.

- Orchard B, MacCann C, Schulze R, Matthews G, Zeidner M, et al. (2009) New directions and alternative approaches to the measurement of emotional intelligence. In C Stough, DH Saklofske, JDA Parker (Eds.) Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications, New York, USA, Pp. 321-344.

- Roberts RD, Schulze R, MacCann C (2008) The measurement of emotional intelligence: A decade of progress?. In GJ Boyle, G Matthews, DH Saklofske (Eds.) The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessmen, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2: 461-482.

- Dawda D, Hart SD (2000) Assessing emotional intelligence: Reliability and validity of the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) in university students. Personality and Individual Differences 28(4): 797812.

- Van der Zee K, Thijs M, Schakel L (2002) The relationship of emotional intelligence with academic intelligence and the Big Five. European Journal of Personality 16(2): 103-125.

- McCrae RR (2000) Emotional intelligence from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. In R Bar-ON, JDA Parker (Eds.) The handbook of emotional intelligence, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Pp. 263-276.

- Joseph DL, Newman DA (2010) Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. Journal of Applied Psychology 95(1): 54-78.

- Barchard KA, Hakstian AR (2004) The nature and measurement of emotional intelligence abilities; Basic dimensions and their relationships with other cognitive abilities and personality variables. Educational and Psychological Measurement 64: 437-462.

- Van Rooy DL, Viswesvaran C, Pluta P (2005) An evaluation of construct validity: What is this thing called emotional intelligence?. Human Performance 18: 445-462.

- Frost BC, Ko CHE, James LR (2007) Implicit and explicit personality: A test of a channeling hypothesis for aggressive behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 92(5): 1299-1319.

- Mc Clelland DC, Koestner R, Weinberger J (1989) How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ?. Psychological Review 96: 690-702.

- Woike BA (1995) Most-memorable experiences: Evidence for a link between implicit and explicit motives and social cognitive processes in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68(6): 1081-1091.

- Schulte MJ, Ree MJ, Carretta TR (2004) Emotional intelligence: not much more than g and personality. Personality and Individual Difference 37(5): 1059-1068.

- Shulman TE, Hemenover SH (2006) Is dispositional emotional intelligence synonymous with personality?. Self and Identity 5: 147171.

- Mayer JD, Roberts RD, Barsade SG (2008) Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology 59: 507-536.

- Costa PT, Mc Crae RR (1992) Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor Inventory professional manual. Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JD (1994) The twenty item Toronto Alexithymia Scale_II. Convergent, discriminant and concurrent validity. J Psychosom Res 38(1): 33-40.

- Boyle G, Stankov L, Cattell RB (1995) Measurement and statistical models in the study of personality and intelligence. In International Handbook of Personality and Intelligence, Sakloske D, Zeidner M (eds.) Plenum: New York, USA, Pp. 417-446.

- Caruso DR, Mayer JD, Salovey P (2002) Relation of an ability measure of emotional intelligence to personality. J Pers Assess 79(2): 306-320.

- Davies M, Stankov L, Roberts RD (1998) Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75(4): 989-1015.

- De Raad B (2005) The trait-coverage of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences 38(3): 673-687.

- Eysenck HJ (1994) Four ways five factors are not basic. Personality and Individual Differences 13(6): 667-673.

- Peabody D (1984) Selecting representative trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52: 552-667.

- Roberts RD, Zeidner M, Matthews G (2001) Does emotional intelligence meet traditional standards for an intelligence? Some new data and conclusions. Emotion 1(3): 196-231.

- Roger D, Najarian B (1989) The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring emotional control. Personality and Individual Differences 10(8): 845-853.

- Stankov L, Crawford JD (1997) Self-confidence and performance on tests of cognitive abilities. Intelligence 25(2): 93-109.

- Warwick J, Nettelbeck T (2004) Emotional intelligence is...?. Personality and Individual Differences 37(5): 1091-1100.

- Cattell HEP (1993) The development of the fifth edition of the 16PF. In S Conn, ML Rieke (Eds.), The Sixteen Personality FactorQuestionnaire fifth edition technical manualChampaign, IL.

- Christal RE (1996) Non-cognitive research involving systems of testing and learning. Final Research and Development Status Report (USAF Contract No. F33615-91-D0010). Armstrong Laboratory, Brooks Air Force Base, United States Air Force.

- Le Breton JM, Barksdale CD, Robin J, James LR (2007) Measurement issues associated with conditional reasoning tests: Indirect measurement and test faking. J Appl Psychol 92(1): 1-16.

- James RL (1998) Measurement of personality via conditional reasoning. Organizational Research Methods 1(2): 131-163.

- James RL, Mazerolle MD (2001) Personality in work organizations. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- James RL, McIntyre MD, Glisson CA, Bowler JL, Mitchell TR (2004) The conditional reasoning measurement system for aggression: An overview. Human Performance 17(3): 271-295.

- James RL, Mc Intyre MD, Glisson CA, Green PD, Patton TW, et al. (2005) Conditional reasoning: An efficient, indirect method for assessing implicit cognitive readiness to aggress. Organizational Research Methods 8: 69-99.

- James RL, Mc Intyre MD (2000) Conditional Reasoning Test of Aggression: Test manual. Innovative Assessment Technology, Knoxville, USA.

- Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P (1999) Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence 27(4): 267-298.

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB (2003) A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality 37(6): 504-528.