Are Perceived Family-Related Social Support and Paternal Age Associated with Peer Victimization in Secondary Education? A Population-Based Study

Bachler Herbert1, Nickel Marius2 and Bachler Egon3*

1Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria

2Medical University Graz, Clinic for Psychiatry, Austria

3PMU Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Institute for Synergetic and Psychotherapy Research, Austria

Submission: November 06, 2017; Published: November 27, 2017

*Corresponding author: Bachler Egon, PMU Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Institute for Synergetic and Psychotherapy-Research. Ignaz Harrer Str.79. Austria, Email: office@dr.bachler.at

How to cite this article: Bachler H, Nickel M, Bachler E. Are Perceived Family-Related Social Support and Paternal Age Associated with Peer Victimization in Secondary Education? A Population-Based Study. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017; 7(4): 555718. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.07.555718

Abstract

Background: Bullying is an important public health issue. We examined perceived family-related social support as a predictor of being a bully, peer victimization, being a bully/victim or an uninvolved pupil. In addition, characteristics of the parental health status and different demographic variables (parental separation, sibling position, death of a parent, parental age, size of the flat) were examined.

Methods: Data were obtained through a population-based cross-sectional study of N=3496 children at the age of 12.6.

Results: Male pupils show an increase of approximately 40 percentage points in the proportion of the bully and bully/victim groups. Pupils with less perceived family-related social support; pupils who have experienced a family break-up without contact to the separated parent; and pupils with a parent with poor physical or mental health show a significantly higher risk for peer victimization. Pupils with fathers of advanced age display a 41 percentage points higher risk for peer victimization.

Keywords: Bullying; Peer Victimization; Social Support; Parenting Behavior; Parental Age; Child And Adolescent Health

Introduction

Bullying is a symmetrical (single or repeated) and interpersonal form of aggressive behavior (physical, verbal, social and electronic). It takes place in preschool, during adolescence and penetrates adult working places. Bullying is a mode of aggression (dominance behavior) in the ongoing process of group organization. Bullying therefore includes different forms of aversive (competitive) behavior (striving for dominance, increase of social status, group position and self-worth, etc.) Wang, Lereya [1-2]. Victimization in the context of the school is a ubiquitous and global social and public health problem, affecting from about 10% up to more than 50% of all children World Health Organization [3]- the numbers varying according to which sets of diagnostic criteria are being used. Victimization shows peaks between the ages of 12 and 14 Liu, Graves [4]. US prevalence rates of school bullying showed that 20.8% of pupils have experienced or engaged in some sort of physical bullying, 53.6% were victims of verbal bullying, 51.4% were victims of social bullying and exclusion, 13.6% had been cyber bullied. Why is empirical research on bullying and peer victimization an important public health issue? Given its proven prevalence, peer victimization is an under estimated, yet common and substantial developmental stress factor for adolescents Gershon et al. [5]; Lereya et al. [2].

In general, the psychosocial development of children and adolescents, especially their individual vulnerability, is critically influenced by adverse and harmful experiences and by resilience factors. Slopen et al. [6] showed that timing and chronicity of exposure to childhood adversity factors influence diverse indicators of long-term health risk in childhood and adolescence. Regardless of different individual and contextual variables in the pathogenesis of mental illness, adults with higher index for childhood adversities have higher odds of mood, anxiety and personality disorders Raposo et al. [7]. There is increasing empirical evidence for a strong relationship between the individual genetic dispositions, individual stress- related epigenetic processes and the individual development of the affect regulation system Cohen et al. [8]. This reciprocal interaction of biological and psychosocial variables is the causal pathway in the development of externalizing and internalizing symptom formation in bullying and peer victimization Pascual- Sagastizabal et al. [9].

We can assume that childhood adversities in general, and peer victimization in particular, are a severe risk factor for psychobiological and interpersonal (mal)-adjustment and mental health problems Arseneault et al. [10]. Victims of persistent bullying dynamics develop temporary and permanent problems, affecting mental and social development respectively psychosomatic health GiniPozzoli et al. [11]. In a meta-analysis Lereya et al. [2] have been able to establish three key factors (predictors) which increase the risk of children becoming victims of bullying or becoming bullies themselves. These are sexual abuse, neglect and maladaptive parenting. Conversely, parenting behavior is an important mediating and protective factor in processing adversity factors, for example in the process of peer victimization (bullying). For instance, authoritarian parenting is associated with bullying and victimization at school Georgiou et al. [12]. Authoritative parenting with high scores on responsiveness, demand and support,leadschildrentobetter developments in the school, to lower rates in terms of social adjustment problems, and generally to better child outcomes Hay, Meldrum, [13]. Parental styles are therefore associated with improved or impaired social functioning. Parental behavior, family environment and executive functions of children are linked Bernier et al. [14]. On the other hand, children from families with incongruous and inconsistent paternal interactive parental behavior, low social support and low child attachment security, which we can find predominantly in families with low socioeconomic status (SES), show more mental health disorders and psychosocial problems McLaughlin et al. [15]. Generally speaking, the index of socio-familial stress is an indirect influencing factor for the development of children (cognitive ability, IQ, social adjustment, social adjustment, severity of mental health problems etc.). Socio-familial adversities act directly on the parental behavior (engaged parents, parental monitoring, enriched environment), mediating the psychosocial development of children Bornstein, Bradley [16]. Our study seeks to examine four groups (bully, victim, bully/victim and uninvolved) in relationship to perceived social support (parenting behavior), parental age and other family characteristics. Our aim was to discover parenting factors and family characteristics which will be essential for an increase or decrease of victimization and bullying. Social support (parental behavior) was operationalized and examined with respect to the characteristics of perceived good or bad communication between adolescents and parents, perceived affectionate- tender relationships between parents and children, perceived parental involvement-support and family-related supervision- monitoring. Finally, we want to derive from the empirical data further results in order to identify evidence-based guidelines for bullying (bullying recommendations) aimed at parents, teachers and physicians (GPs and pediatricians),which should allow an early detection and prevention of peer victimization.

Methods

Participants

A random sample from urban and rural public secondary schools was collect edit one Austrian federal state (Tyrol). The overall sample was N=3454 children at the age of 12.6 (+/- 1.3); 51% of the participants were male and 49% were female. Respondents were excluded if the questionnaire was not fully (age of the father, age of the child, bully/victim, health of the child) or not plausibly (n1=29.1%) completed, or if the child was older than 15: n2 = 789 (23%). Our final dataset included N=2637 pupils. Mean age was 12.59 (+/- 1.3) (uninvolved, N=2002, 51% female, 49% male); 12.51 (+/- 1.31) (victim, N=412, 49% female, 51% male); 12.8 (+/- 1.31) (bully/victim, N=96, 28% female, 72% male); 13.17 (+/- 1.36) (bully, N=127, 30% female, 70% male). The questionnaires were always distributed to the entire class. We surveyed 30 schools in a population-based cross-sectional study. Four school classes are socio-demographically set within a town of about 10,000 to 15,000 inhabitants; most of them (26) come from more rural regions with under10, 000 inhabitants. Teachers were instructed by an accompanying letter; a hotline was installed for further questions. Data were collected through anonymous self-report questionnaires which were distributed in the classroom. Following instructions, the pupils were asked to fill out the questionnaires simultaneously, either online on a PC (N1=3031) or in a paper pencil version (N2=423).After this procedure the questionnaires were collected.

Measures and Procedure

We used a self-completion questionnaire (TGAM - Bullying Questionnaire Tyrolean Society of General Medicine, consisting of 58 items) which included questions about bullying, victimization, personal and family resources, socio demographic variables, health outcomes, as well as items about social support (parenting, siblings, relatives, classmates, friends, teachers, etc.). Bullying and victimization were assessed by 15 items (TGAM 1-15), modeled upon the School-Mobbing Questionnaire (SMOB) Kasper, Heinzelmann-Arnold [17]. The SMOB has five subscales ("attacks on your relationships,""you are rejected by others," "attacks on the image that you have in others," "others demand things of you that you feel are offensive" and "you are experiencing violence or threats of violence") and can be answered with yes or no. It also address the frequency of peer victimization (daily, weekly, monthly; general recurrence).

The interrater-reliability is indicated as high (>.80) by the test authors. Items about engaging behavior of minors were taken from PISA (2009) with a Cronbach a of .94 Bergmuller [18]. (TGAM items 16-18). Items 19-34 (complaints from the internalizing spectrum) were taken from PISA 2009. Items 3543 about perceived social support were taken from the Berlin Social-Support Scale (BSSS). The original BSSS includes six independent subscales (perceived available support, need for support, support-seeking, actual received support, provided support and protective buffering) and measures the cognitive and behavioral dimension of social support. We used one subscale (perceived available support, with 8 items). Each two items capture qualitative aspects of parent-adolescent communication, their emotional relationship, perceived involvement-support between adolescents and parents, and perceived family-related (parental) supervision-monitoring.

All 8 items were rated according to whether social support has been given either from parents, siblings, relatives, classmates, friends, teachers or others, or whether a pupil has no perceived social support at all. All four dimensions of parental behavior were operationalized separately with two items. The perceived social support was coded as ++ = good, ~ = average and - = bad with the index p. Where perceived social support was coded as an index of the siblings was used as index for siblins: (s + = good communication with sibling, s - = bad communication with sibling ore other). Respondents had to rate their agreement with the statements on a four-point scale (strongly disagree (1), somewhat disagree (2), somewhat agree (3) and strongly agree (4)). An average mean within the range of 1-4 was calculated for the subscale. A higher score indicated a greater burden. Cronbach a for the four subscales of the BSSS ranges from 70 to 86 Schwarzer [19]. Items 4458 from TGAM assess different socio-demographic variables. We assessed family characteristics by single items (parental age, family break-up, family break-up without contact to the separated parent, level of occupation of parents, number and age of siblings, number of rooms of the flat, death of a parent and serious physical or mental illness of a parent). Gender was measured as male and female; age was written down. Grade was recorded directly. Children were classified as uninvolved, victim, bully or bully/victim. Victimization and bullying were defined as scoring higher than one point on the victim-scale and bullying-scale respectively (eight-point scale from 0 to 7; [0 to 1] = uninvolved, [2 to 7] = bullying). The objective was to estimate the population percentages of bullies, victims and bully/victims with the precision of a 95% confidence interval for each group.

Data Analysis

We used R version 3.1.1 (2014-07-10) database for our data analysis, with adjustments for stratification clustering and weighting. Descriptive statistics were obtained for the classification of the three subgroups (bully, victim and bully/ victim), parenting behavior and parental characteristics. Next we analyzed our data set with logistic regression (multinomial logistic model MNLM)in order to compare bullies, victims, bully/ victims and uninvolved pupils and address the question as to how these groups are associated with perceived parental support and different socio-demographic variables of the families. Descriptive analysis was applied to the general characteristics of the represented study group. We used logistic regression in the examination of hypotheses. We attested four models in our analysis and fitted several regression models separately for each bullying classification.

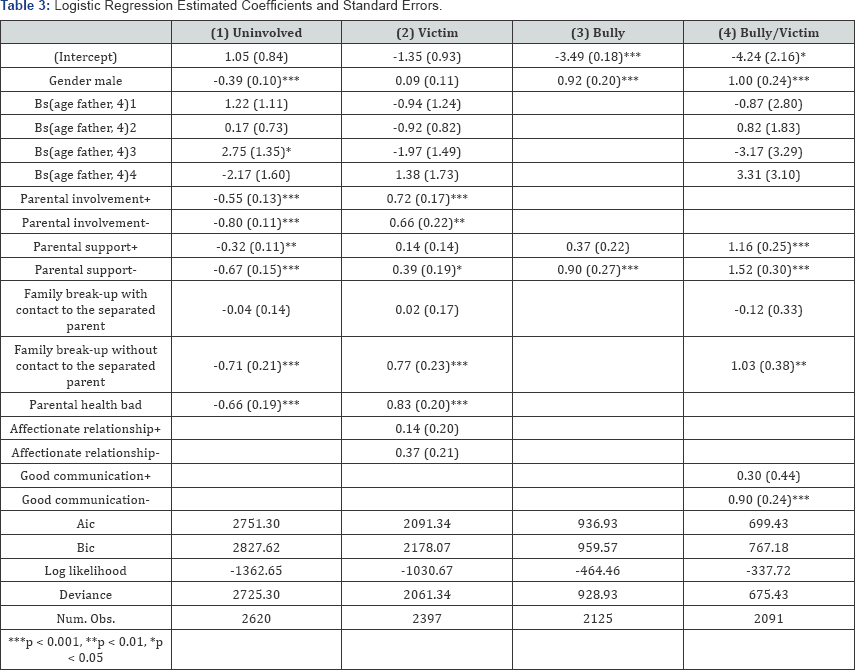

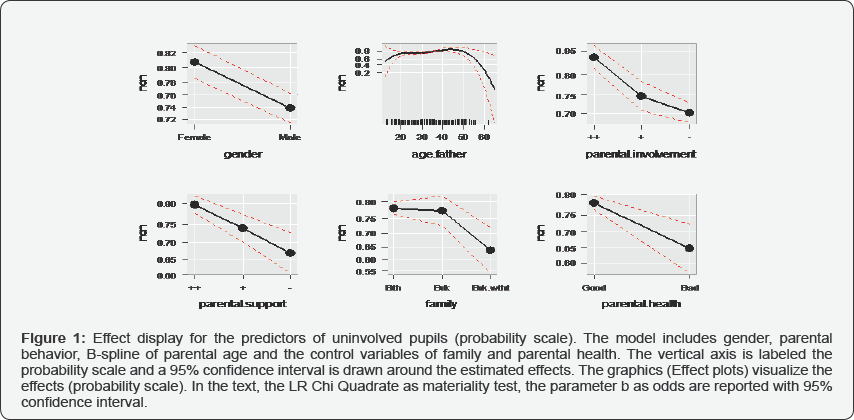

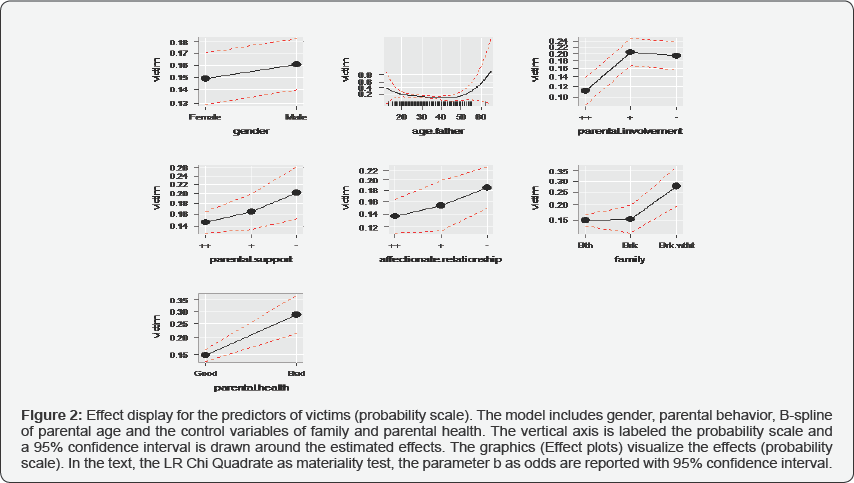

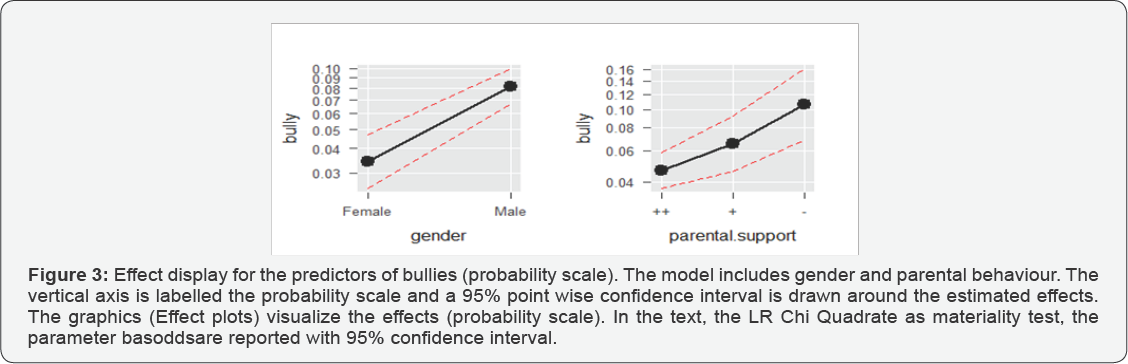

In a first step all models contained the following variables: parental age (father), good communication, affectionate relationship, parental involvement and support and parental supervision/monitoring. The analysis was also controlled for age, gender, family characteristics (both parents present, family break-up with contact to the separated parent, family break-up without contact to the separated parent) and parental health. A backward selection procedure using Akaike's information criterion as a stopping rule was used in order to identify relevant factors in the analysis. Note: Model (1) "uninvolved vs. involved" includes all cases; models (2) "victim vs. uninvolved, (3) "bully vs. uninvolved" and (4) "bully/victim vs. uninvolved" are to be understood as a subsample of model (1). The predictors for parental behavior were added to the model as factors, and age was added as a predictor of a third-degree polynomial (B-spline basis for polynomial splines). In a subsequent chapter (see "Results") the significant models are indicated. A more detailed description can be found in table 1 which shows the parameters (estimate) including the associated standard errors (Std. Error). The graphics (effect plots) visualize the effects (probability scale). In the text, the LRchi square as materiality test and the parameter b as odds are reported with a 95% confidence interval. The indication of percentage points equal to the probability difference between the lowest and the highest value derives from effect plots.

Results

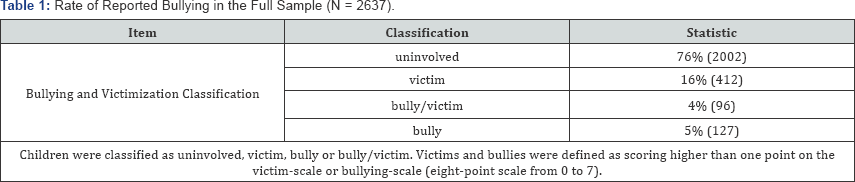

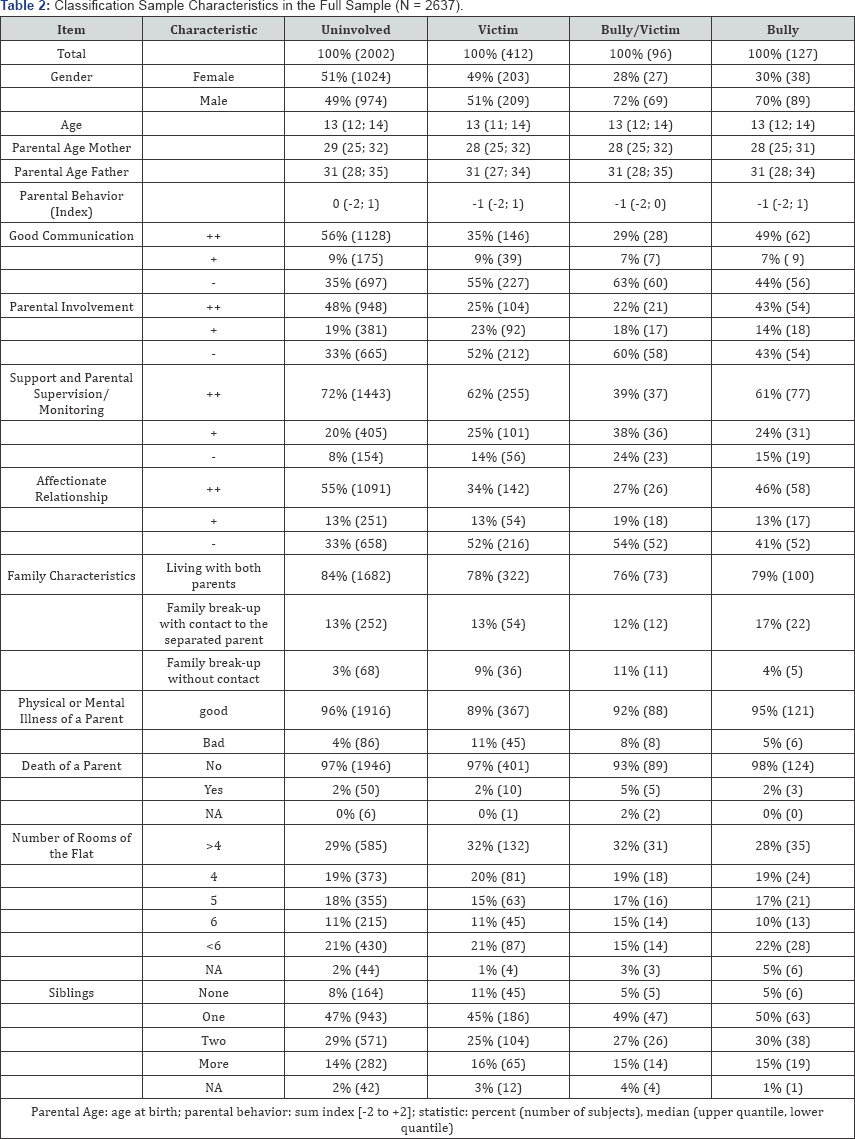

Of the 2,637 students included in our study 49% (1292) were girls and 51% (1341) were boys. The average (median) age was 13 (12-14). Table 1 shows a classification of the tested pupils. Table 2 shows the descriptive characteristics of the sample. The descriptive data show differences in the gender distribution: Male pupils display an increase of approximately 40 percentage points in the proportion of the bully and bully/ victimgroups. Aspects of parental behavior (perceived family related support) are reflected in different distributions in each of the groups: Victims and bully/victims show a lower proportion of positive behavior. Parental age, family characteristics, parental health, number of rooms and the number of siblings show no descriptively interpretable differences in distribution. Table 3 shows the parameter estimates results for our models are given in table 3. For all analyses "perceived parental support" showed significant positive effects, which means that lower parental support is associated with a higher risk of being a bully. In contrast, parental age in the victim and victim/bully groups shows a statistically tend effect.

Uninvolved vs. involved model (1): In model (1) statistically significant effects are seen in the parental age of the father (LR chisq = 31.11, p = .023), with two subscales of parental behavior, i.e. involvement (LR chisq = 55.01, p <. 001) and parental support (LR chisq = 21.65, p < .001). The covariates show gender (LR chisq = 11.17, p < .001), family (LR chisq = 11:56, p = .003) and parental health (LR chisq = 12.25, p < .001) as statistically significant. In detail, the effect is through parental involvement with OR = 0.45 95% CI = [0:36 to 0:56] meaningful In the case of negative parental involvement the likelihood of bullying rises by about 14 percentage points, as shown in Figure 1 (see the difference between (++) and (-)). Negative parental support OR = 00:51, 95% CI = [0:38 - 0.69] increases the probability by 13 percentage points. The effect of the father's age is [0.00 - 2.65], with OR = 00:11, 95% CI = not exhaustive due to the CIs. In the model children with older fathers (> 50) are 56 percentage points more likely to show a hit than children with fathers in the central region (35 to 45). The Figure further suggests that in children with young fathers (up to 20 years) the likelihood of bullying is also increased. And it is a non-linear relationship it demonstrates a U-shaped curve. The covariate family OR = 0.49 95% CI = [0:33 - 0.73] increases in break-ups without contact: The probability of bullying is affected by 15 percentage points.Parental health OR = 12:52, 95% CI = [0:36 - 0.74]: A parent in poor health increases the probability by 13 percentage points. The influence of gender OR = 0.67, 95% CI = [0:56 - 0.81] leads to the conclusion that a boy's risk to be affected increases by 7 percentage points (Figure 2).

Victim vs. uninvolved model (2): In model (2) statistically significant effects are seen in three subscales of parental behavior effects in parental involvement (LR chisq = 18:35, p < .001). Statistical effects tend to show the variables of parental support (LR chisq = 4.52 p = .104) and affectionate relationship (LR chisq = 3.16, p = .206). The covariate gender (LR chisq = 0.61, p = .435) is not significant; family (LR = 10.27 chisq, p = .006) and parental health (LR chisq = 15:51, p < .001), on the other hand, are significant. The parental age of the father (LR chisq = 8.23, p = .083) tends to be significant. In detail, clear effects are shown in the event of parental involvement with OR = 1.93, 95% CI = [1.25 - 2.98]. In the case of negative parental involvement the odds increase by about 9 percentage points. Affectionate relationship OR = 1:45, 95% CI = [0.96 - 2.17] and parental support OR = 1:47, 95% CI = [1:02 to 2:12] display interpretable factors of 5 percentage points and 6 percentage points respectively. The covariates of family OR = 2.16, 95% CI = [1:37 to 3:41] at about 13 percentage points and of parental health OR = 2.30, 95% CI = [1:54 to 3:42] at 14 percentage points also show significant effects. The effect of the father's age, at OR = 3.96, 95% CI = [12:13 -> 10], cannot be judged clearly and is estimated in the model to amount to about 41 percentage points.

Bully vs. uninvolved model (3): Model (3) shows two items of statistical significance: parental support (LR chisq = 10.61, p = .005) and gender (LR chisq = 23:26, p < .001). It shows OR = 2.46 95% CI = [1:44 to 4:20] for parental support. In the case of negative support the probability increases by 6 percentage points. Gender OR = 2.52, 95% CI = [1.70 - 3.72] proves that to be a male student increases the probability of being a bully by 5 percentage points. The scales for health and family, however, have to be interpreted with caution because only little data are available for analysis. An influence of the father's age cannot be derived from the data.

Bully/victim vs. uninvolved model (4): Model (4) displays statistically significant effects for gender (LR chisq = 19:15, p < .001), parental support (LR chisq = 33.46, p < .001), good communication (LR chisq = 14.61, p = .001) and family (LR chisq = 6.77, p = .034), with the parental age of the father showing statistically significant influences (LR chisq = 4.99, p = .288). In detail, the effects are as follows: A significant effect of parental support OR = 1:47, 95% CI = [1:02 to 2:12] is displayed, resulting in an increase in probability by 7 percentage points. Good communication OR = 2.45, 95% CI = [1.52 - 3.95] has a small effect, showing an increase in probability by 3 percentage points. The effect of the covariate of family OR = 2.81, 95% CI = [1.33 - 5.96] is significant and leads to an increase of 5 percentage points. When gender OR = 2.72, 95% CI = [1.70 - 4:35], a smaller influence of 3 percentage points is indicated. The effect of the father’s age at OR = 27.43, 95% CI = [00:06 -> 10] cannot be assessed exhaustively; in the model the effect corresponds to an increase in older fathers by 28 percentage points (Figure 3).

Discussion

Prevalence of bullying, victimization and bully/victimization: Depending on the diagnostic criteria used, bullying and victimization affect about 10% to 32% of all children, 57.7% of the respondents were not involved in bullying World Health Organization [3]. Our data show that 72% of the pupils of our sample were uninvolved; 4% of our respondents were rated as bullies, 16% as victims and 5% as bully/victims. These differences are due to different cut-off values, the age of the sampled children (age 12.6, +/- 1.3) and operationalization. In addition, Analitis et al. [20]. Researched the percentages of bullies and victims in a cross-national sample in 11 European countries. Five countries (Austria, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland and the UK) showed an elevated likelihood of reported peer-victimization (ages 8-18). Probably our data show lower rates of bullies and victims because our sample is primarily composed of schools out of rural areas.

Gender

Bullying is primarily for both genders a trait and not a situational state. A gender-related effect was not found in peer victimization Cambodia Goossens [21]. But in self-reports boys exhibit more physical and direct forms of aggression; girls report more indirect and relational forms of bullying Nansel et al. [22]. Boys who are bullies try to seek acceptance by showing antisocial behavior. Bullying girls seek acceptance especially of boys (Liu & Graves, 2011). Our descriptive data show differences in the gender distribution: Male pupils display an increase of approximately 40 percentage points in the proportion of the bully and bully/victim groups.

Grade

Bullying and victimizations show the highest peaks between ages 12 and 14 Liu, Graves [4]. Girls and boys at the age of 13 are most vulnerable to be affected by bullying. This peak is confirmed by our data (age 12.6, +/- 1.3).

Perceived parental social support

In terms of qualitative characteristics of communication, affectionate-tender relationship between parents and adolescents, or the grade of parental involvement-support, as well as parental or family related supervision-monitoring): Evans, Steel [23]. Demonstrated for a sample of maltreated children the positive influence of perceived social support (family, friends and others) on the development of long-term trauma symptoms. Storm et al. [24]. Confirmed the close connection between perceived parental or classmate support of bullied adolescents and long-term consequences specially their ability to work, their social self-preservation ability and the use of social support systems. Roth on, Head, Kleinberg, Stansfeld 2011 revealed that social support as a mitigating effect in regard to the effects of stressful adverse life events like peer victimization. In detail, our data showed a clear effect with regard to parental involvement: The odds of peer victimization increase by about 9 percentage points; affectionate relationship and parental support display interpretable factors of 5 and 6 percentage points respectively.

Parental Age

Svensson et al. [25] demonstrate that, on average, advanced parental age (fathers aged 50 or older, or younger than 20) results in higher grades (an increase of 0.3 points) than fathers aged 30 to 34; but they did not find any influence on the development of intelligence. The other way round Weiser, Reichenberg, Werbeloff, Kleinhaus, Lubin, Shmushkevitch, Davidson 2008 proved the association between an advanced paternal age and weak social functioning in the general population. The prevalence of poor social functioning of male adolescents increased when the father was younger than 20 years (odds ratio OR 1.27, 95% confidence interval CI 1.08-1.49) and of young pupils fathers aged 45 (OR 1.52, 95% CI, 1.43-1.61). In comparison, Weiser et al. [26] demonstrated that the mother's age at the birth of male adolescents also showed a "U-shaped" pattern for the normal population. If male offspring had at the time of birth a mother younger than 20 years they showed an increasing prevalence rate of poor social functioning (OR 1.21, 95% CI, 1.16-1.27) and male adolescents of mothers older than 40 years at the birth displayed following OR (1.61, 95% CI, 1.52-1.71).

Miller et al. [27] showed that an advanced parental age is associated with higher rates of suicide and different increased risk of severe disease in the offspring. Autism, schizophrenia, ASD, social competencies, etc. is associated with an advanced parental (paternal) age Weiser et al. [26] our data analyses showed a "U-shaped" pattern. Male adolescents in the group of victims (paternal age at birth ≥ 50 years) displayed a risk of peer victimization elevated by 41 percentage points compared to that of male adolescent children of fathers aged 35-40 (OR = 3.96, 95% CI = [12:13 -> 10]). This is remarkable: Because every twentieth child in Germany has a father over 50 and every fourth a father over 40.Studies on parental age and being bullied are still notably lacking in the literature. How can these overdetermined associations be explained? Kong, Frigge, Masson, Besenbacher, Sulem, Magnusson, Stefansson 2012 demonstrated that the age of the father at conception is associated with mutations. The causal genetic pathways of the relationship between advanced parental age at birth and poor psychosocial functioning (which mediates victimization) is associated with deregulations of epigenetic processes Perrine, Brown, Malaspina [28] and immaturity of spermatids, low activity of DNA repair processes and lower function of antioxidant enzymes. This is the most prominent evidence-based biological mechanism by which the father's or the mother's parental age affects mental diseases and the behavioral expressions of social functioning. However, in addition to that we still know little about the socio- psychological differences in parenting styles between older and middle-aged parents. Possibly older parents tend to educate their offspring more permissively; but the economic and social background of older couples is usually better for a child than that of younger couples; security is a valuable asset to education and relationship building.

The empirical data on risks for the offspring of parents of advanced age leads to unresolved questions and will necessarily lead to further discussions, as late pregnancies will become more common ("social freezing") due to the achievements of reproductive medicine. Socio-demographic variables of the families (family break-up, family break-up without contact to the separated parent, educational level of each parent, number and age of siblings, number of rooms of the flat, death of a parent and serious physical or mental illness of a parent): Empirical research on parenting behavior and inter-parental relations demonstrates that bullies, victims and bully/victims show higher maternal neglect. The living reality of bullies and non-bullies differs significantly in regard to illegal behavior, psychological aggression, physical assault and sexual coercion Keelan et al. [29].

Bullies display a higher frequency of watching television and lacking teacher reports. They also show signs of having been bullied themselves and have experienced a family environment and parents who do not have high expectations regarding their children’s school support system Barboza et al. [30]. Tippett Wolke [31]. Demonstrated in a meta-analysis that victims and bully/victims were more likely to come from low socioeconomic households. McLaughlin et al. 2012 showed that SES and adolescent mental disorders are, most directly, the result of perceived low social status and weak family-related resources. In this context, the parental educational level is the most important indicator of SES and is related to victimization Jansen et al. [32].The four subgroups in our sample show fewer differences with regard to family characteristics (both parents present, family break-up, family break-up without contact to the separated parent), physical or mental illness of a parent, death of a parent, number of rooms of the flat and number of siblings. Pupils who have experienced a family break-up without contact to the separated parent show an approximately 13 percentage points higher risk of peer victimization and those with physically or mentally ill parents a 14 percentage points higher risk [33-38].

References

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR (2009) School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J Adolesc Health 45(4): 368-375.

- Lereya S T, Samara M, Wolke D (2013) Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: a meta-analysis study. Child Abuse Negl 37(12): 1091-1108.

- C Currie, C Zanaotti, A Morgan, D Currie, M Looze et al. (2012) World Health Organization Risk behaviours: Being bullied and bully others. (Eds.) Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No.6) pp. 191-200.

- Liu J, Graves N (2011) Childhood bullying: a review of constructs, concepts and nursing implications. Public Health Nurs 28(6): 556-568.

- Gershon A, Sudheimer K, Tirouvanziam R, Williams LM, O Hara R(2013) The long-term impact of early adversity on late-life psychiatric disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 15(4): 352.

- Slopen N, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD (2014) Cumulative adversity in childhood and emergent risk factors for long-term health. J Pediatr 164(3): 631-638.

- Raposo SM, Mackenzie C S, Henriksen CA, Afifi TO (2013) Time Does Not Heal All Wounds: Older Adults Who Experienced Childhood Adversities Have Higher Odds of Mood, Anxiety, and Personality Disorders. Am J GeriatrPsychiatry 22(11): 1241-1250.

- Cohen S, Janicki Deverts D, Doyle WJ, Miller GE, Rabin BS (2012) Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(16): 5995-5999.

- Pascual Sagastizabal E, Azurmendi A, Braza F, Vergara AI, Cardas JJ et al.(2014) Parenting styles and hormone levels as predictors of physical and indirect aggression in boys and girls. Aggress Behav 40(5): 465473.

- Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S (2010) Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems much ado about nothing. PsycholMed 40(5): 717-729.

- Gini G, Pozzoli T (2013) Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 132(4): 720-729.0020

- Georgiou SN, Fousiani K, Michaelides M, Stavrinides P (2013) Cultural value orientation and authoritarian parenting as parameters of bullying and victimization at school. Int J Psychol 48(1): 69-78.

- Hay C, Meldrum R (2010) Bullying victimization and adolescent selfharm: testing hypotheses from general strain theory. J Youth Adolesc 39(5): 446-459.

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Deschenes M, MatteGagne C (2012) Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: a closer look at the care giving environment. Dev Sci 15(1): 12-24.

- McLaughlin KA, Costello EJ, Leblanc W, Sampson NA, Kessler RC (2012) Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. Am J Public Health 102(9): 1742-1750.

- Bornstein M, Bradley R (2003) socioeconomic status, parenting and child development. Monographs in parenting. Psychology Press Taylor and Francis Group, New York, USA.

- Kasper H, Heinzelmann-Arnold I (2010) Student bullying- we should do something against it. Buxtehude AOL.

- Bergmüller S (2007) Academic stress among adolescents: development conditions, mediating processes and consequences; an empirical study in PISA 2003. Hamburg Kovacs.

- Schwarzer R Berlin Social-Support Scales (BSSS). pp 73-82.

- Analitis F, Velderman MK, Ravens-Sieberer U, Detmar S, Erhart M, et al.(2009) Being bullied: associated factors in children and adolescents 8 to 18 years old in 11 European countries Pediatrics. European Kid screen Group 123(2): 69-77.

- Camodeca M, Goossens FA, Terwogt MM, Shuengel C (2002) Bullying and victimization among school-age children: Stability and links to proactive and reactive aggression. Social Development 11(3): 332-345.

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons Morton B, et al. (2001) Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 285(16): 2094-2100.

- Evans SE, Steel AL, DiLillo D (2013) Child maltreatment severity and adult trauma symptoms: does perceived social support play a buffering role. Child Abuse Negl 37(11): 934-43.

- Strom IF, Thoresen S, Wentzel Larsen T, Sagatun A, Dyb G (2014) A Prospective Study of the Potential Moderating Role of Social Support in Preventing Marginalization Among Individuals Exposed to Bullying and Abuse in Junior High School. J Youth Adolesc 43(10): 1642-1657.

- Svensson AC, Abel K, Dalmann C, Magnusson C (2011) Implications of advancing paternal age: does it affect offspring school performance. PLoS One 6(9): e24771.

- Weiser M, Reichenberg A, Werbeloff N, Kleinhaus K, Lubin G et al. (2008) Advanced parental age at birth is associated with poorer social functioning in adolescent males: shedding light on a core symptom of schizophrenia and autism. Schizophrenia Bull 34(6): 1042-1046.

- Miller B, Alaraisanen A, Miettunen J, Jarvelin MR, Koponen H et al.(2010) Advanced paternal age, mortality, and suicide in the general population. J NervMent Dis 198(6): 404-411.

- Perrin MC, Brown AS, Malaspina D (2007) Aberrant epigenetic regulation could explain the relationship of paternal age to schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 33(6): 1270-1273.

- Keelan CM, Schenk AM, McNally, Fremouw WJ (2014) The interpersonal worlds of bullies: parents, peers, and partners. J Interpers Violence 29(7): 1338-1353.

- Barboza GE, Schiamberg LB, Oehmke J, Korzeniewski S, PostL A, et al. (2009) Individual characteristics and the multiple contexts of adolescent bullying an ecological perspective. J Youth Adolesc 38(1):101-121.

- Tippett N, Wolke D (2014) Socioeconomic status and bullying: a metaanalysis. Am JPublic Health 104(6): 48-59.

- Jansen PW, Verlinden M, Dommissevan Berkel A, Mieloo C, vander Ende J et al. (2012) Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: do family and school neighbourhood socioeconomic status matter. BMC Public Health 134(3): 473-80.

- Hensley V (2013) Childhoodbullying: a reviewandimplicationsforhealth care professionals. Nurs Clin North Am 48(2): 203-213.

- Kong A, Frigge ML, Masson G, Besenbacher S, Sulem P, et al. (2012) Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father's age to disease risk. Nature 488(7412): 471-475.

- Krishnaswamy S, Subramaniam K, Indran H, Ramachandran P, Indran T (2009) Paternal age and common mental disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry 10(4-2): 518-523.

- Rothon C, Head J, Klineberg E, Stansfeld S (2011) Can social support protect bullied adolescents from adverse outcomes? A prospective study on the effects of bullying on the educational achievement and mental health of adolescents at secondary schools in East London. J Adolesc 34(3): 579-88.

- Vreeman RC, Carroll AE (2007) A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med 161(1): 78-88.

- Wolke D, Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ (2013) Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. PsycholSci 24(10): 1958-1970.