The Benefits of Therapy Dogs on StudentWellbeing within a UK University

Sanjidah Islam, Elizabeth Spruin* and Ana Fernandez

Department of Psychology, Canterbury Christ Church University, England

Submission: September 21, 2017; Published: October 04, 2017

*Corresponding author: Elizabeth Spruin, School of Psychology, Politics and Sociology, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 1QU, England, Tel: 7817245365; E-mail: Liz.Spruin@canterbury.ac.uk.

How to cite this article: Sanjidah I, Elizabeth S, Ana F. The Benefits of Therapy Dogs on Student Wellbeing within a UK University. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017; 7(1): 555702. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.07.555702.

Abstract

Whilst research has found that the use of therapy dogs in universities can provide a number of positive benefits, the vast majority of this research is based on qualitative outcomes in North American universities. The present study therefore aims to explore how therapy dogs can alleviate student anxiety, with particular focus on the role that physical interaction may play within this process. The study further aims to be the first to investigate the impact of therapy dogs in the setting of a British university. Twenty students delivering individual class presentations were recruited for the study. A therapy dog was made available to all participants before their presentation, and the level of interaction was noted by the researcher. Each participant was also asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Short Form before and after they gave their presentation. Results indicated that those who interacted with the therapy dog reported significantly lower levels of state anxiety after the presentation compared to those that did not interact with the dog. These findings suggest that the use of therapy dogs can decrease levels of anxiety in university students and enhance their overall wellbeing. The implications of these findings, along with limitations of the study are discussed below.

Keywords: Therapy dogs, higher education, stress, wellbeing, student support

Introduction

Therapy dogs provide emotional support for people through their calm demeanours, friendly attitudes, and sensitivity to human emotions Fine as cited in Jalongo, McDevitt [1]. They are trained for the purpose of delivering emotional support, and differ from typical family pets by their calming temperaments Jalongo, McDevitt [1]. These dogs have been found to have multiple benefits for human wellbeing through their calm and friendly nature. Due to their numerous benefits, more recently, therapy dogs have begun to be utilised in school settings Stevenson [2]; Sutton [3], where research has found that children with learning disabilities become more social and engaging in class when a therapy dog is present Stevenson [2]. Research has further indicated that therapy dogs can also benefit the academic performance of students. For instance, Sutton [3] found that using time with a therapy dog as a reward for improved academic achievement was a successful motivator in encouraging students to achieve higher.

Most recently, researchers have turned their attention to how therapy dogs can benefit the student population in universities Jalongo, McDevitt [1]; Lannon, Harrison [4]. University can be a stressful time for some students, with exam stress and pressure from deadlines, as well as the loneliness that oftentimes accompanies students who are moving to a new location Burns [5]. In addition to this, research suggests that as many as three-quarters of undergraduate students also work alongside studying, which could add to their experience of stress Gallavan, Benson [6]. These stress factors have been shown to have an impact on student mental health. For example Zivin [7] suggested that around 60% of students may suffer with mental health problems which are induced by stress. Whilst student support services are available, research suggests that alternative forms of emotional support should be explored to ensure overall student wellbeing Stewart [8], thus giving rise to the notion of therapy dogs in universities.

Research investigating therapy dogs in university settings have generally reported favourable results. Jalongo, McDevitt [1] ran a pet therapy program during an exam period at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Students were encouraged to stop by at the university library and join the therapy dogs. Students were then requested to complete a brief qualitative survey about how the therapy dog affected their mental state during this time, where 95% of students agreed that the therapy dog helped them to relax and focus. Similar results were found at McGill University in Canada when they ran a therapy dog program during the exam period Lannona [4]. The sessions lasted around two hours, with students dropping in at any time during those two hours. Students were subsequently requested to provide feedback on their stress levels before and after attending the program, and 94.7% reported a decrease in stress levels, with no students reporting any increase in stress.

Although these studies provide some support for the benefit of therapy dogs to alleviate stress at university, this body of research lacks reliable methods of measuring stress. For instance, the Jalongo, McDevitt [1] study simply asked participants whether they felt relaxed, whilst the Lannon [4] study used a generic scale that has not been suggested by research to be a valid or reliable measurement of stress. Accordingly, whilst both studies found positive outcomes for the use of therapy dogs on student stress, further research using more reliable measurements of stress are necessary Oei [9]; Nichols, Maner [10].

Stewart [8] made use of reliable measurements of anxiety in their study, which investigated the effects of student interactions with a therapy dog. The therapy dog was located in popular student accommodation where students were encouraged to take a moment to interact with the therapy dog. Interactions included; petting the dog, sitting near the dog, cuddling the dog, and feeding treats to the dog. The event occurred twice a month for a term, and students were requested to complete the Burns Anxiety Inventory Burns [5]; as cited in Stewart [8] before and after meeting the therapy dog. Findings included that students reported lower levels of anxiety after meeting the therapy dog, and 84% of students isolated physical interaction with the therapy dog as being the highest contributing factor to their reduced levels of anxiety. Despite the positive findings, the researchers state that more research exploring the impact that various forms of physical interactions with a therapy dog may have is needed Stewart [8].

Furthermore, although the use of therapy dogs in a university setting is a relatively new concept, there is growing research highlighting the possible benefits that these dogs can have on student stress. That being said, all the research to date investigating therapy dogs in universities is predominantly carried out in North America Jalongo, McDevitt [1]; Lannon [8]. Research has highlighted differences between American and British cultures, particularly in the area of mental wellbeing Mertin [11]. This leads to questioning whether the findings of previous studies carried out in North America can be replicated in a British university, and if so, to what extent can anxiety be alleviated by therapy dogs.

The current study therefore explores whether therapy dogs can alleviate student anxiety, with particular focus on the role physical interaction may play within this process. The study further aims to be one of the first to investigate the impact of therapy dogs in the setting of a British university, while also using reliable measures to do so, with the hopes of laying down the foundations on which future studies can be carried out. The present study will investigate the impact of therapy dogs on levels of anxiety in students delivering presentations in class, while also focusing on the role of physical interaction.

Method

Participants

All participants recruited were female and part of the same third year psychology module. In total, 20 female undergraduate students approached to participate in the study agreed to take part, and agreed to the presence of a therapy dog throughout the duration of their module. The participants ages ranged from 20 to 23 years (M = 20.70, SD = .87).The majority of the sample identified as White British (n = 18; 90%), with the remaining identifying as Black British (n = 1; 5%), and Mixed Race (n = 1; 5%).

Materials

Participants were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory short form (STAI-6; Marteau, Bekker [12]. The STAI- 6 consists of six items related to anxiety (calm, tense, upset, relaxed, content, and worried), all of which are rated on a four- point scale, with higher scores indicating more anxiety. The STAI-6 is reported to have good reliability and validity, and has been found useful in assessing subjective anxiety levels Maissi [13]. The STAI-6 was used at two assessment points; before participants delivered a class presentation, and again once the participant completed their class presentation. The STAI-6 was found to have a high internal reliability within the sample, with a Cronbach's Alpha score of .92. Participants were asked two further open-ended questions upon delivering their presentations; 1) how they felt the therapy dog impacted their presentation and 2) if they had physically interacted with the therapy dog prior to their presentation.

Procedure

All participants enrolled on a third year psychology module were asked prior to the commencement of the module if they consented to a therapy dog being present throughout the duration of the eight week module. Participants were also provided with the details of the study and asked if they would like to engage with the research. Upon gaining consent from all participants, the therapy dog attended six of the eight two- hour sessions. Participants were advised that the therapy dog would arrive 15 to 20 minutes early so that students had time to interact with the dog and also to ensure the dog had time to familiarise herself with the new location and settle down.

As part of the module, at the start of every session a group of students would deliver a presentation pertaining to a specific topic The students presenting were asked to fill in the STAI- 6 prior to their presentation, and were asked to complete the same measure after they had presented, along with two further questions relating to their interactions with the therapy dog. Both pre- and post-presentation questionnaires took approximately 5 minutes to complete, after which participants were debriefed verbally and thanked for their assistance with the research.

Results

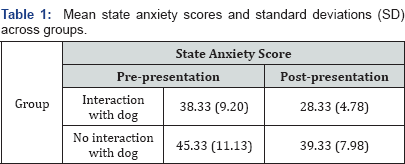

All analyses reported were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics v23.0.0.3. Given the low sample size, it was not possible to carry out analysis of variance. Instead, independent-samples t-tests were carried out to compare the levels of pre- and postpresentation state anxiety (as measured by the STAI-6) between the group that interacted with the dog and the group that did not interact with the dog. Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for these comparisons.

The t-tests revealed no difference in state anxiety between the groups prior to their presentation, t (18) = 1.53, p = .143, d=.72. However, the group that interacted with the dog reported significantly lower levels of state anxiety after the presentation compared to the group who did not interact with the dog, t (18) = 3.74, p = .002, d=1.76. Interestingly, paired-samples t-tests showed that the group that interacted with dog exhibited a significant reduction in state anxiety scores post-presentation, t (9) = 3.50, p = .007, d = 1.01, whereas there was no significant reduction in state anxiety in the group that did not interact with the dog, t (9) = 1.75, p = .115, d =.55.

Discussion

The current study sought to establish whether therapy dogs can be used as an effective tool for reducing levels of anxiety in students, and to elucidate the role that physical interaction with the dog may play in this process. The findings indicated that the mere presence of a therapy dog may not be sufficient in reducing state anxiety in students during stressful conditions; rather, physical interaction may be needed in order to relieve state anxiety.

These findings are in line with previous research which has found that student feedback on therapy dog programs highlights physical interaction with the therapy dog as the most important factor in enhancing their wellbeing Stewart [8]. The inclusion of a quantitative measure of anxiety in the present study strengthens extant findings and extends previous research. For instance, studies have found that university students in the company of a therapy dog report lower levels of anxiety Jalongo, McDevitt [1] and stress Lannon [4], but these studies do not provide detail into the extent of the interaction between the students and therapy dog; thus, it is unclear whether students engaged with the therapy dog or were simply in its presence. The current study however provides evidence to suggest that physical interaction with the therapy dog may be key in alleviating anxiety.

This can be seen as strength of the current study, as it is the first study, to the best of the author's knowledge, to investigate the effects of physical interaction with a therapy dog on student wellbeing using a valid and reliable form of measurement. The current study is also the first piece of research to investigate the benefits of therapy dogs in a British university; where previous studies have largely investigated North American populations Jalongo, McDevitt [1]; Stewart [8]. Due to the novel elements of the current study, future research is needed to build on these findings, with particular focus on investigating the impact that specific types of interactions with a therapy dog may have on student anxiety, and how this can be adapted to design longer- term programmes.

Despite the various benefits and novel aspects of the current research, there are a number of limitations within it. For instance, the sample of the present study was small and homogeneous, and additional research should be carried out to replicate the findings in a larger and more diverse sample, thereby allowing more generalizable results to be established. That being said, the effect sizes ranged from medium to large in strength, which suggests that the effects of the findings are relevant irrespective of sample size. The present study also did not provide a baseline measurement of state anxiety before participants were exposed to the therapy dog, and there was no control group to compare findings to. Whilst future research should seek to address these drawbacks, this is the first study to highlight the effect of the interactions with a therapy dog and the potential benefits this can have on the student experience and wellbeing.

Implications of this study are therefore far-reaching, as universities could look towards using therapy dogs as a source of enhancing student wellbeing. Previous research has highlighted how student support services are possibly lacking Eisenberg [14], and may not be able to reach out to their target audience Julal [15]. Research using therapy dogs with student populations have suggested that these types of programmes are in demand by students Stewart [8], and have also been used to bridge the gap between students and student support services Daltry, Mehr [16].

In essence, this research provides support for the efficacy of therapy dogs in improving student wellbeing. If students are less anxious, this could positively impact their academic performance and attendance, which would then benefit the university as well as the individual. Based on this research and other literature discussed, therapy dogs can be recommended for universities seeking to provide better support for their students. Similarly, while this study did not directly recruit students with mental health issues, and therefore no claims can be made about the impact of therapy dogs on student mental health, the findings could be used to highlight how therapy dogs can aid in counteracting the factors that could be associated with mental health problems, such as high le

Conclusion

Overall, this study provides support for North American- based research into the efficacy of therapy dogs in a British university setting. Physically interacting with a therapy dog was found to have a positive impact on student anxiety after delivering a class presentation. Despite the low sample sizes, the moderate to high effect sizes indicate that the findings are solid. The current study sets the groundwork into the benefits of therapy dogs with further research needed to build on the findings presented. That being said, the implications of this type of research, and the potential for developing this area further are considerable, especially in terms of providing alternative types of student support and enhancing the student experience.

References

- Jalongo MR, McDevitt T (2015) Therapy dogs in academic libraries: A way to foster student engagement and mitigate self-reported stress during finals. Public Services Quarterly 11(4): 254-269.

- Stevenson K, Jarred S, Hinchcliffe V, Roberts K (2015) Can a dog be used as a motivator to develop social interaction and engagement with teachers for students with autism? Support for Learning, 30(4): 341363.

- Sutton H (2017) Therapy dogs can be successful motivating students with autism spectrum disorder. Disability Compliance for Higher Education 22(7): 9.

- Lannon A, Harrison P (2015) Take a paws: Fostering student wellness with a therapy dog program at your university library. Public Services Quarterly 11(1): 13-22.

- Burns RB (1991) Study and stress among first year overseas students in an Australian university. Higher Education Research and Development 10(1): 61-77.

- 6. Gallavan NP, Benson TR (2014) Getting on the same page: Expanding student support services to increase candidate success and educator accountability. Action in Teacher Education 36(5-6): 490-450.

- Zivin K, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E (2009) Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117(3): 180-185.

- Stewart LA, Dispenza F, Parker L, Chang CY, Cunnien T (2014) A pilot study assessing the effectiveness of an animal-assisted outreach program. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 9(3): 332-345.

- Oei TPS, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F (2013) Using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. International Journal of Psychology 48(6): 1018-1029.

- Nichols AL, Maner JK (2008) The good-subject effect: Investigating participant demand characteristics. The Journal of General Psychology 135(2): 151-166.

- Mertin P, Dibnah C, Crosbie V, Bulkeley R (2001) Using North American instruments with British samples: Norms for the revised children's manifest anxiety scale in the UK. Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review 6(3): 121-126.

- Marteau TM, Bekker H (1992) The development of a six-item short- form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychology 31: 301-306.

- Maissi E, Marteau T, Hankins M, Moss S, Legood R, et al. (2005) The psychological impact of human papillomavirus testing in women with borderline or mildly dyskaryotic cervical smear test results: 6-month follow-up. British Journal of Cancer 92: 990-994.

- Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Gollust SE (2007) Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care 45(7): 594-601.

- Julal FS (2013) Use of student support services among university students: Associations with problem-focused coping, experience of personal difficulty and psychological distress. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 41(4): 414-425.

- Daltry RM, Mehr KE (2015) Therapy dogs on campus: Recommendations for Counseling Center Outreach. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 29(1): 72-78.