The Perception of Positive Behavioral Support

*Bronwen Elizabeth Lesley Davies

Clinical Psychologist, Llanfrechfa Grange Hospital, UK

Submission: August 23, 2017 Published: Septmber 08, 2017

*Corresponding author: Bronwen Elizabeth Lesley Davies, Clinical Psychologist, Llanfrechfa Grange Hospital, UK; Tel: 4 41633623572; Email: Bronwen.Davies2@wales.nhs.uk

How to cite this article: Bronwen E L. The Perception of Positive Behavioral Support. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017; 6(3): 555690.DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.06.555690

Abstract

Positive Behavioral Support (PBS) is a values based framework for the assessment and management of challenging behaviour. Assessments and interventions should be informed and valued by the active participation of multiple stakeholders, including the focus individual. The aim of the current review was to evaluate previously published research on perceptions of PBS. A systematic literature search identified eleven qualitative studies that were evaluated for methodological quality and then subjected to meta-ethnographic review process. Quality ranged from medium to high and the meta-ethnographic approach yielded four super-ordinates, third order.

Keywords: Individual factors; Organizational factors; Process factors; The relationship

Introduction

Positive Behavioral Support (PBS) is a framework for developing via functional analysis an understanding of a person's challenging behaviour, which is then used to develop effective support NHS England and Local Government Association [1]. PBS is a multi-component framework employing ethical, socially valid techniques in management of challenging behaviour and has primarily been implemented within intellectual disability [ID] services Carr [2] and schools Sugai et al. [3] as well as in other health and social care settings Allen [4] and is widely endorsed MIND, 2013, 2015; Royal College of Nursing, 2013; NHS Protect, 2014; Department of Health, 2014; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015a and b; Skills for Care and Skills for Health, 2014.

Any assessment or intervention implemented within the PBS framework should ideally be informed and valued via the active participation of multiple stakeholders, including the focus individual. Consideration is given by stakeholders of appropriateness of PBS interventions and their 'goodness of fit' with the focus individual and the systems supporting them Carr et al. [2]; Gore et al. [5]. Hence, PBS explicitly promotes 'an egalitarian approach towards stakeholder participation which has become a normative feature of PBS' Carr et al. [2]. The current review is aimed at understanding stakeholder's perceptions of PBS. In order to identify and determine the extent and quality of research in this domain, a systematic review and meta-synthesis of relevant qualitative research studies was conducted with a focus on studies that have reported on the views and experiences people involved in PBS across a range of organisational settings (e.g. ID services, education, juvenile justice).

Method

The search strategy

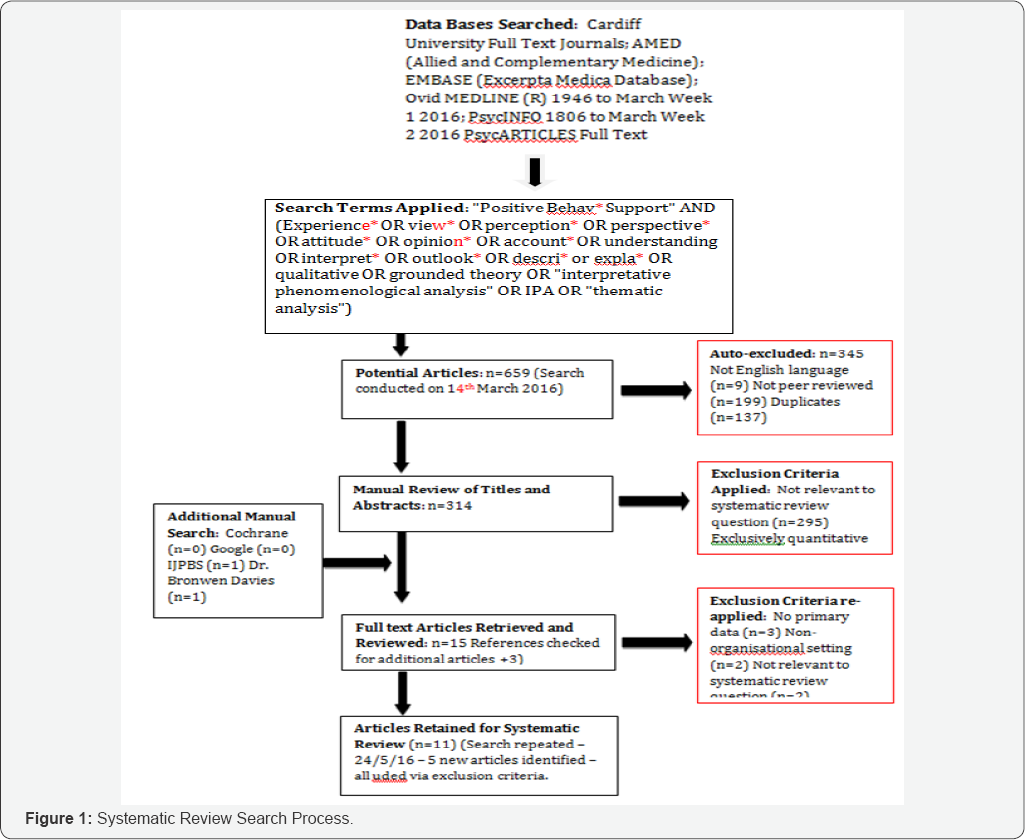

a) The OvidSP platform was used to access a total of six electronic databases on 24th March 2016:

a. Cardiff University Full Text Journals

b. AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine)

b) EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database]

a. Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to March Week 1 2016

b. Psyc INFO 1806 to March Week 2 2016

c. Psyc ARTICLES Full Text

Additionally, both the Cochrane Library and a key journal, The International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support (IJPBS), were hand-searched. The lead author [GK] also reviewed the references of retrieved full-text articles and received a relevant 'in press’ article Davies [6] which was subsequently published during preparation of the original work, a doctoral thesis April, 2016.

Search strategy

The formal search strategy utilised two groups of search terms, namely Positive Behav* Support AND Experience* OR view* OR perception* OR perspective* OR attitude* OR opinion* OR account* OR understanding OR interpret* OR outlook* OR descri* or expla* OR qualitative OR grounded theory OR «interpretative phenomenological analysis» OR IPA OR thematic analysis. Inclusion criteria for publication included publication after 1990 in English and use of either a qualitative or mixed methodology. Exclusion criteria were duplicate articles, publication in non-peer review journals, Studies that have an exclusively quantitative methodology, studies with no primary data (e.g. direct quotations from participants), studies investigating non-organizational/non-professionalised settings (e.g. families) and all forms of 'grey literature' (e.g. review articles, commentaries, discussion pieces). Similarly, studies that did not explicitly report upon views or experiences of PBS were also excluded.

The complete process is shown in (Figure 1). This process, as shown, resulted in eleven papers being identified for inclusion in the review and meta-synthesis (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

All eleven articles employed a qualitative methodology and are summarized in Appendix A. The framework developed by Cardiff University's Support Unit for Research Evidence (SURE) [7] was used to assess the methodological quality of each study, incorporating as it does the sub-fields of CASP [8] qualitative checklist with the addition of an extra field: consideration of issues relating to potential author sponsorship / conflicts of interest. The SURE was used to assign each study a score of 0,1or 2 for each sub-field:

a) 0 - This score indicates there to be no consideration given to the question posed by the quality review framework.

b) 1 - This score indicates there to be partial consideration given to the question posed by the quality framework or that issues were addressed however limitations were present.

c] 2 - This score indicates the article clearly addressed the question posed by the quality review framework in a clear and rigorous fashion.

d) The scores allocated to each study together with a total quality score from 0-80 are shown in Appendix B.

Synthesising Reviewed Studies

A meta-ethnographic approach Noblit and Hare [9] was employed as the basis of the meta-synthesis Ring, Ritchie, Mandava, and Jepson [10]. The meta-ethnographic approach involves a sequence of seven stages

a] Getting started [in this case, the initial systematic literature search]

b] Confirming initial interest [i.e. literature screening and quality reviewing]

c] Reading studies and extracting data

d] Determining how studies are related (identifying common themes and concepts]

e] Translating studies (checking first and/or second order concepts and themes against each other] Synthesising translations (attempting to create new third order constructs and

f] Expressing the synthesis. Much meta-ethnography utilises Schutz's [11] notion of 'first-order', 'second-order' and 'third-order' constructs. First order constructs reflect participants' understandings, as reported in the original studies (e.g. direct quotations], second order constructs reflect the authors' interpretation of the participants' understanding and third order constructs reflect the subsequent interpretation of the original authors' interpretation. Typically, the 'data' or 'building blocks' of the meta-ethnographic approach are the second-order constructs within the original studies Britten et al. [11], Toye et al. [12] and this was the focus of the current synthesis.

Results

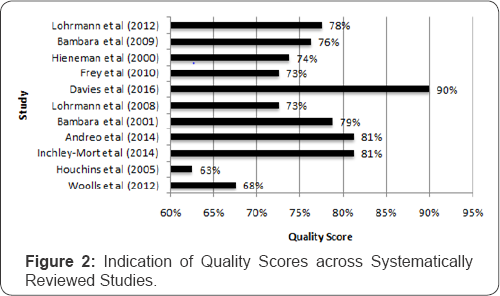

The quality of the eleven studies in the current review was variable with total quality scores ranging from 50 to 72 (62.5% to 90% quality].

It was considered that studies scoring over 80% were of ‘high’ quality, studies scoring between 70%-80% were ‘medium- high’ and studies scoring between 60%-70% were of ‘medium’ quality. (Figure 2) below shows the quality score for each study rounded to the nearest whole percentage number (Figure 2). As shown, most studies (n=6] are of medium-high quality (70%- 80%], two studies are of medium quality (60%-70%] and three studies are of high quality (>80%]. Therefore, all eleven studies were taken forward to the next stage of the review.

In all studies, data collection methods, analyses and interpretative procedures were well described and triangulation was employed in cases to improve the validity of findings. However, most of the studies lacked a rationale for the specific methodology used, did not examine the relationship between researcher(s] and participants, did not report on data saturation and there was a general absence of information relating to research governance, for example, how the research was presented to participants or how ethical approval was obtained.

Two of the three high quality studies explored views of focus individuals who the PBS approach was implemented for. Both Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6] and Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13] reported themes that described the importance placed on relationships of ‘understanding’ within PBS, they identified similar barriers to implementation and commonly concluded that PBS is perceived to be 'valued’ and 'acceptable’ to most focus individuals, also pointing out that future research needs to further explore the experience of focus individuals. The other high quality study, Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] reported on the importance of contextual adaptations in order to sustain PBS, in particular the fostering of environments described as ‘flexible’, ‘creative’ and containing ‘foresight’.

Those studies considered to be medium-high quality were rated so due to a lack of consideration of researcher position, data-saturation and wider ethical considerations. They reported on barriers to implementing PBS being consistent with broader personal and organisational implementation patterns that need to be overcome Lohrmann [15], Lohrmann [16], systemic and resource issues (including culture, support, use of time and focus-individual involvement] that can impede or facilitate implementation. It was identified that PBS plans need to be contextually relevant, person-centred and based on available resources Hieneman and Dunlap [17]. The goals and outcomes of PBS need to be supported by key stakeholders, however the procedures required to implement PBS received less support from a social validity perspective Frey, Lee Park, Browne- Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18]. Team members’ perceived the social processes of PBS to be most important and that future research needs to more fully understand the social contexts in which PBS is implemented Bambara, et al. [19].

The two medium quality studies lacked information on sampling strategy, participant selection, data saturation and comparability with other studies. Houchins, et al. [20] concluded that multiple themes relating to PBS centre around 'environmental congruence', and as such, contextual issues need to be addressed if PBS is to generalise to juvenile justice settings. Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] similarly concluded that themes relating to the implementation of PBS interact in ways that can affect the success of PBS interventions.

Service Contexts

Of the eleven studies reviewed, four were undertaken in community-based ID services Bambara, et al. [19] Hieneman and Dunlap [17]; Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13]; Woolls, Allen, and Jenkins [21], all of which were adult services with the exception of Hieneman and Dunlap's [17] study conducted in services for children with disabilities. The most common service context were primary and secondary schools or other educational settings Andreou, [14], Bambara, Nonnemacher, and Kern [19]; Frey, et al. [18]; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin, and Palmieri [22]; Lohrmann, and Patil [23] and all referred to PBS with typically-developing children with the exception of Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] that concerned children with ID. The remaining two studies were undertaken in forensic contexts, Davies, Mallows and Hoare's [24] study within a secure forensic mental health hospital and Houchins, et al. [20] study in a secure juvenile justice facility with high levels of a diagnosed mental health problems. Three studies, Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6], Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13] and Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21], were British and the other eight were from the United States of America.

Study aims

Four of the studies had very general, explorative aims concerning stakeholder perceptions of PBS within a service setting more globally, i.e. 'applicability of PBS' in a service Houchins, et al. [20] or stakeholder 'experiences' or 'perspectives' of PBS within a service Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin,[19] ; Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6], Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13]. Four of the studies were a little more specific in that their aim was the identification of factors relating to the efficacy of PBS. Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] aimed to identify 'supportive' and 'problematic' factors, Hieneman and Dunlap [17] aimed to establish 'factors that affect success', Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] aimed to investigate 'barriers' and 'facilitators' and Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] aimed to explore 'factors that help and hinder' PBS. Similarly, two studies by the same lead author had aims that related to understanding pre-determined intra-staff factors in relation to PBS application i.e. 'resistance' Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15] and 'buy-in' to PBS Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16] Lastly, the study conducted by Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18] was different to the others in their specificity of aim: to assess the social validity of PBS.

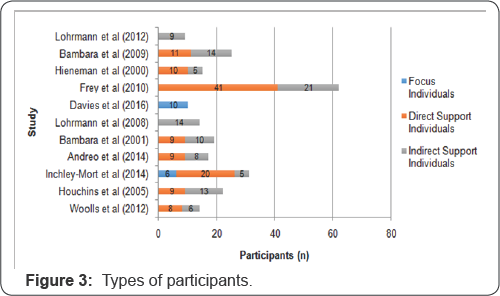

All of the studies reviewed demonstrated that a range of individuals can hold a stake in PBS, these can be broadly organised as: individuals who are the recipients of PBS (focus individuals), the individuals directly involved in its delivery (direct-support individuals) and the individuals involved in supervising and / or training those individuals directly involved (indirect-support individuals). Typically, direct-support individuals included 'support workers', 'teachers' or 'careers' and were characterized by having a direct 'face to face' role with the focus individual and normally spend the majority of their time in direct contact. Indirect-support individuals typically included 'behaviour specialists', 'consultants' or 'administrators' and are characterized by having a direct role with the direct- support individuals and sometimes an intermittent role with focus individuals.

All of the studies reviewed here investigated at least one of the above types of stakeholder (i.e. focus individual, direct- support individual or indirect-support individual), with many investigating a mixture in some form. Figure 3 illustrates the spread of participants across the three sub-types for all eleven studies reviewed here (Figure 3).

As shown in (Figure 3), the largest sub-group investigated were direct-support individuals (n=117), with indirect-support individuals closely following (n=105). It is clear that focus individuals as a sub-type are relatively under-represented within the studies (n=16). Regarding gender of participants, five studies did not report or provided unclear information Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19], Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno and Korfhage [25]; Hieneman and Dunlap[17]; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15]; Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16]. Of the remaining six studies in which gender was clearly reported, these studies contained 71 female support- individuals and 26 male support-individuals.

For focus individuals’ gender: 15 were male and 1 was female. Whilst the sample sizes here are small, there is a skewed picture in terms of support-females (n=71) being far better represented than support-males (n=26). The opposite skew is apparent in the focus individuals (albeit an even smaller sample) whereby male focus-individuals (n=15) are far better represented than female focus individuals (n=1). The skew in support individuals is likely representative of the general picture of support individuals within the teaching and caring professions, whereby females are better represented than males. The skew of male focus-individuals may be due to the inclusion of Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6] study, which accounts for the majority of focus individual participants in the current review, sampled from male-only hospital wards.

The final key characteristic of consideration is the quality and quantity of participant experience with PBS. Of the eleven reviewed, seven made reference to their participants having received 'training' in PBS Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] ; Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] ; Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno and Korfhage [25]; Hieneman and Dunlap [17]; Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20]; Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16]; Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] . There was generally a lack of detail regarding the quality and quantity of the training received; it is therefore difficult to make judgments on the quality of participants expertise with PBS based on the presence or not of training. As such, every study comments that participants have 'experience' of PBS in vivo. This experience is most commonly measured in years and was used to determine inclusion for studies in some cases. A single study required participants to have at least one-year minimum experience Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] another required 1.5 years minimum experience Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] four studies reported participants having minimum experience of two years Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] ; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15]; Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16], one study reported three years minimum experience Hieneman and Dunlap [17] and one study reported five years minimum experience Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] . Lastly, two studies reported that participants had experience of PBS but they did not offer any quantification of this Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno and Korfhage [25]; Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13]. With regard to the studies involving focus-individuals Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6]; Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13] only Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6] provide information relating to the nature of their involvement, stating service users were involved in the development of plans and also provide information for each participant regarding the length of time they have had a PBS plan in place, which offers an indication of the time individuals have been 'receiving PBS'.

Some studies in the current review presented additional information to control for the efficacy or fidelity to PBS. Two studies reported that the fidelity or efficacy of PBS (as measured by the School-wide Evaluation Tool] at each site where participants were drawn as between 86%-89% Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] and 80%-99% Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16]. Three other studies made references to informal fidelity or efficacy measures, such as selecting only participants 'successful' in PBS Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19]; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15], the reported presence of 'key positive behaviour support characteristics’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19] p.215] or components of PBS such as functional assessment Hieneman and Dunlap [17].

All studies in the current review used cross-sectional designs with qualitative methodologies to examine reported outcomes associated with the use of PBS and compare these with qualitative findings. All studies employed either individual semi-structured interviews or focus groups with participants, with one study using both Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21]. Nine of the studies reported that data was audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed, of the remaining two studies, one employed 'detailed' note taking during focus groups Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] and the other did not report how verbatim data was recorded Hieneman and Dunlap [17].

All studies reviewed here adopted a process of coding the data in order to progressively abstract themes (or equivalent]. Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] used a grounded theory approach, with four studies Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke, and Xin [19] ; Houchins & Jolivette, 2005; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15]; Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16] using approaches consistent with the grounded theory methodology citing either a process of open coding or constant comparative analysis without actually presenting a grounded theory. Two studies Hieneman and Dunlap [17]; Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13] reported use of content analysis. Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18] report using thematic analysis, Davies, Mallow and Hoare 2016 used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA], Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] used a critical incident technique that identified specific and observable behavioural events and Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] used a modified "consensual qualitative research process" to identify codes and core ideas. Every study included a process of triangulation to improve the reliability and validity of identified themes (or equivalent). All studies except Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] employed multiple researchers as part of the coding and theme development process, with Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] using a separate focus group to triangulate data. Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15], in addition to the use of multiple researchers, checked codes at a later stage with participants to increase validity. Of all studies in the current review, only Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] proposed a theoretical model in attempt to explicitly explain the interrelation of their resultant themes, grounded in the data.

Meta-ethnographical synthesis

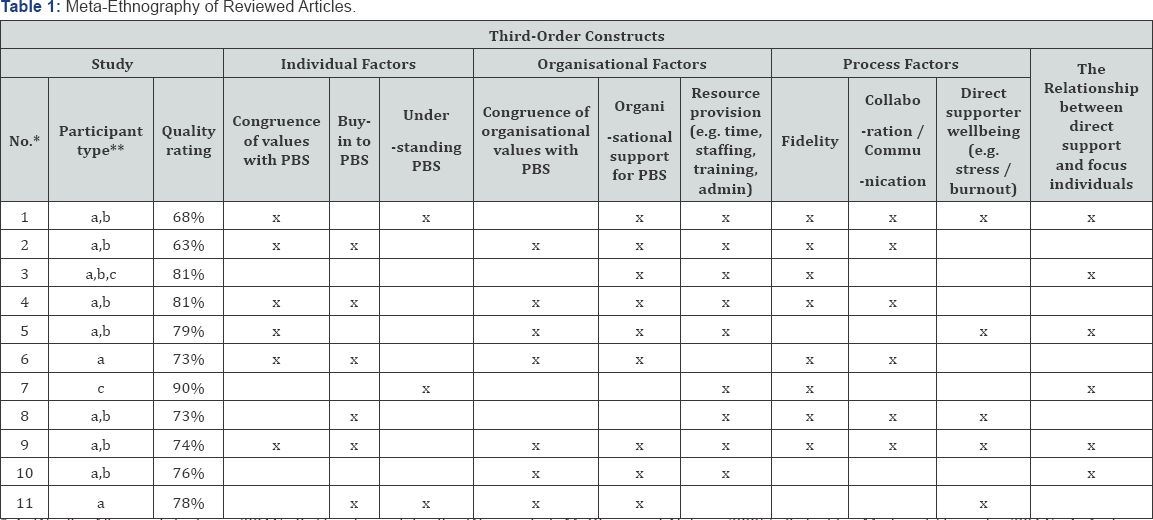

Four superordinate and nine subordinate third-order constructs were developed and entered into a grid format in order to indicate where each construct was translated from preexisting constructs from within the studies (see Table 1 below). As per Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., and Pill, R. (2002], each column of the grid represents a third order construct. In labelling the third order constructs, the first author used terminology relating to the most relevant and prevalent themes and concepts from each of the studies under review (Table 1).

*1. W oolls, Allen and Jenkins (2011); 2. Houchins, Jolivette, W Vessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson (2005 ; 3. Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis (2L 14); 4. Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn (2014); 5. Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O'Rourke and Xin (2001); 6. Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri (2008); 7. Davies, Mallows and Hoare (2016); 8. Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage (2010); 9. Hieneman and Dunlap (2000); 10. Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern (2009); 11. Lohrmann, Martin and Patil (2012)

**‘Participant types: a=Indirect supporter, b=direct supporter, c=focus individual

Individual Factors

Congruence of values with PBS: A perception existed across studies that individuals involved in the delivery of PBS possessed personal values that were more or less congruent with the values associated more generally with PBS. A number of studies described this as the participants' 'philosophy' or ‘guiding values’ fitting with the model Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19], their ‘match with prevailing philosophy’ Hieneman and Dunlap [17], their ‘philosophical agreement’ Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] , ‘philosophical difference’ Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15], ‘conflict in personal beliefs’ Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] or whether they ‘embrace’ the PBS model Woolls, Allen and Jenkins, 2012.

Buy-in to PBS: Another term used to describe similar phenomenon is whether individuals 'buy in' to the approach at an attitudinal level Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14]; Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20]; Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16]. In some circumstances, studies related this ‘fit’, ‘match’, ‘agreement’ etc. to the individuals view or opinion on using positive reinforcement and preventative strategies as oppose to punitive responses Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] ; Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20]; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15] or ‘consequences’ Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14,25-31]. A similar attitudinal theme is that the individual ‘fit’ with PBS is related to their level of ‘scepticism’, ‘resistance’ Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno and Korfhage [29]; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri,[15], or negative beliefs regarding the effectiveness of PBS Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno and Korfhage [25]; Hieneman and Dunlap [17]. Additionally, several participants stated that positive attitudes promoted good PBS practice. These included ‘commitment’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19]; Woolls, Allen and Jenkins, 2012, ‘ownership’ of the model Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14], ‘empathy’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann- O’Rourke and Xin [19] and ‘optimism’ or ‘energy-level’ for the approach Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno and Korfhage [25]; Hieneman and Dunlap [17].

Understanding PBS: Some studies reported that participants understanding of PBS varied. This individual understanding related to PBS as a whole and encompassed ‘knowledge and understanding of PBS’ Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21], ‘how I understand PBS’ Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6] and ‘staff not understanding PBS’ Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16] .

Organisational Factors

Congruence of organisational values with PBS: Many of the themes across the studies emphasised congruence of values between the organisation and its practitioners. This was demonstrated by reference to the ‘ecological congruence’ with PBS Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] , the ‘fit’ of PBS practices within the school context Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14], PBS as a broader ‘world view’ or ‘philosophy’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19], the 'responsiveness' and 'flexibility of the system’ in relation to PBS Hieneman and Dunlap [17], the 'culture' of the organisation 'sharing a common understanding and appreciation for PBS’ Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] and the impact of 'climate and system influences' on the application of PBS Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16] .

Organisational support for PBS: A common perception across most studies was that those directly supporting focus individuals valued the indirect support offered from their organisation, regarding this as central to delivering effective PBS. This notion of support appeared in multiple thematic forms including, for example: 'the visibility of external support’ Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21]; the 'availability and frequency of contact’ with indirect supporters Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13]; 'access to external expertise’ Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14]; 'organisational structure in support of PBS important’ Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14]; the 'importance of district and principal level support, leadership and promotion of PBS' Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] and 'support for the team’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19] . Similarly, another study reported a barrier to implementing PBS 'when PBS lacks support at higher levels of administration’ Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15].

Resource Provision: Several themes were identified that related a need for specific organisational provisions for PBS in order for its successful implementation in practice, particularly with regard to staff, including 'staff team stability' Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21], issues of difficulty occuring when there is increased 'staff-turnover’ Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14] , 'too few support staff’ Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18], 'staff resources' Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6] and 'failures to hire staff’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann- O’Rourke and Xin [19] . Related themes included organisational provision of 'time' required to implement PBS, and that 'limited time' can impact service delivery negatively Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18]; Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] together with the time needed for training, learning, collaboration, communication and co-ordination Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] and time for team meetings Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19]; Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern[19] .

Process Factors

Fidelity: Of the process factors within the identified themes, the most commonly occuring related to maintaining fidelity to the PBS approach, for example 'consistency' of applying PBS Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14]; Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6]; Frey, Lee Park [25]; Hieneman and Dunlap [17]; Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20]; Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13] ; Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15]. Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21] similarly describe this as a process of 'getting it right’ and Hieneman and Dunlap [17] refered to the 'integrity of implementation’. Additionally, both studies involving focus indivudals raised similar issues around their perception of PBS plan implementation i.e. 'staff not following guidelines put in place’ Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13], p234 and 'staff fidelity to the plan' Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6].

Collaboration / Communication: A number of studies also cited poor communication between support individuals as a barrier to the PBS process, which was variously described as 'poor internal communication’ Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18] 'communication' Hieneman and Dunlap [17]; Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] and 'communication between staff’ Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21]. Similarly, the importance of collaboration between staff members was seen as beneficial and decribed in terms of 'networking and connections’ between individuals who implement PBS Andreou, McIntosh, Ross and Kahn [14], 'collaboration among providers - support providers working together’ Hieneman and Dunlap [17] , 'the importance of teams supporting each other in order to support people with challenging behaviour' Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19] and also in the negative as 'non-collaboration' between staff being a barrier to PBS implementation Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15].

Direct supporter wellbeing : Several studies contained reference to PBS being perceived as stressful for its advocates, for example 'support dealing with stress of challenging behaviour’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin, [19] 'intra-personal stress level’ Woolls Allen and Jenkins [21] , 'burnout' Frey, Lee Park, Browne-Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18] and a negative impact on 'emotional wellbeing’ Hieneman and Dunlap [17] and 'staff morale’ Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16] .

The relationship between direct support and focus individuals The relationships between direct supporters and focus individuals was commneted on in several studies, being variously described as 'knowing the service user' Woolls, Allen and Jenkins [21]; 'talking about behaviour and being listened to’ and 'understood’ Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13]; 'understanding the person’ and 'seeing the person as a person’ Bambara, Gomez, Koger, Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Xin [19]; 'understanding me and sharing my story’ Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6]; 'relationship with the individual' Hieneman and Dunlap [17] and 'family', 'student' and 'community involvment' Bambara, Nonnemacher and Kern [19] ; Frey, Lee Park, Browne- Ferrigno, and Korfhage [18].

Somewhat surprisingly, studies with relatively higher ratios of indirect support individuals Houchins, Jolivette, Wessendorf, McGlynn and Nelson [20] or those studies with samples that were exclusively indirect support individuals Lohrmann, Forman, Martin and Palmieri [15] Lohrmann, Martin and Patil [16] did not generate explicit themes concerning the relationship with the focus individual. In direct contrast, the two studies that contained focus individuals Davies, Mallows and Hoare [6]; Inchley-Mort and Hassiotis [13] both had core themes concerning the relationship between support individuals and the focus individual and specifically a need for ‘understanding’ between them.

Discussion

The eleven studies reviewed were of medium- to high- quality, which facilitated the subsequent meta-ethnographic synthesis that revealed four super-ordinate third-order constructs: Individual factors; Organizational factors; Process factors and The relationship. The meta-ethnography suggests that individual factors such as the congruence of personal values with those of PBS, the individual's degree of ‘buy-in’ to the approach and their understanding of it are likely important factors in the perception of PBS. With regards to organizational factors, the meta-ethnography suggests that, similarly to the individual factors, congruence of values with those of PBS is also perceived to be important at an organizational level.

It is also suggested that more general support for PBS at an organizational level is important along with the provision of resources to support the implementation of PBS. Additionally, a number of process factors are perceived as important which include: the maintenance of fidelity to the PBS process; the need for inter-staff collaboration and communication and the importance of positive wellbeing for those direct supporters involved. Lastly, the relationship between direct supporter and focus individual is perceived to be important when implementing PBS. Most studies explore the experience and perceptions of indirect and direct support individuals. Given that nearly all studies make some thematic or conclusive reference to the importance of context and inter-relation between individuals, there is a need for research that takes a 'whole picture' approach of the multiple individuals involved in PBS, especially focus individuals, who are largely underrepresented.

In some studies, both focus-individuals and direct-support individuals perceived their relationship to be centrally important when implementing PBS and there is a need for further research to explore the nature of the relationship between focus individuals and support staff from both perspectives. This systematic review demonstrates that the current research base relating to qualitative perceptions of PBS has clear scope for further research. At present, most of the research concerns school-wide PBS or PBS within ID contexts, there is hence a clear need to explore and determine the generalisability of PBS in other contexts where PBS might take place. There was a lack of detail in the qualitative studies regarding the quality of PBS training received and the fidelity of PBS delivered by support individuals. Quality of training is likely to affect individual perceptions of PBS, as such, this needs to be addressed in future research. Similarly, future research in this field needs to be methodologically robust, with greater attention to quality assurance in several areas including specifying why certain methodologies were used or how the stance of the researchers might influence data analysis and identification of themes.

Particular implications for clinical practice include the need to include the vaules of the model within training and ensuring that training results in a good understanding of the model. This can be acheived through knowledge testing after training and supervision by experienced professionals when staff are involved in the PBS process. Fidelity can be improved with interventions such as positve monitoring (Porterfield, 1987). In addition protocals and agreement regarding the implementation of PBS should involve all levels of organizational management in the aim of promoting a shared understanding and commitment to the adoption of PBS and clear pathways for its implementation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review has used a meta- ethnographic analysis to draw out themes across the qualitative research body related to PBS. This research has taken place over multiple clinical fields and contexts where the qualities of the papers were between medium and high. Meta-ethnographic synthesis revealed four super-ordinate third-order constructs: Individual factors; Organizational factors; Process factors and the relationship. Based on the review of the research to date recommendations have been made for future research and potential clinical implications were identified.

References

- Andreou TE, McIntosh K, Ross SW, Kahn JD (2014) Critical Incidents in Sustaining School- Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. The Journal of Special Education pp. 1-11.

- Bambara LM, Gomez O, Koger F, Lohrmann-O'Rourke S, Xin YP (2001) More than techniques: Team members' perspectives on implementing positive supports for adults with severe challenging behaviors. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 26(4): 213-228.

- Bambara LM, Nonnemacher S, Kern L (2009) Sustaining School- Based Individualised Positive Behavior Support Perceived Barriers and Enablers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 11(3): 161176.

- Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, et al. (2002) Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of health services research and policy 7(4): 209215.

- Carr EG (1999) Positive behavior support for people with developmental disabilities: A research synthesis. AAMR.

- Carr EG, Dunlap G, Horner RH, Koegel RL, Turnbull AP, et al. (2002) Positive behavior support evolution of an applied science. Journal of positive behavior interventions 4(1): 4-16.

- Davies B, Mallows L, Hoare T (2016) Supporting me through emotional times, all different kinds of behaviour. Forensic mental health service users understanding of positive behavioural support. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 27(4): 530-550.

- Department of Health (2014) Positive and Proactive Care: Reducing the Need for Restrictive Interventions. London.

- Frey AJ, Park KL, Browne-Ferrigno T, Korfhage TL (2010) The social validity of program-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 12(4): 222-235.

- Gore NJ, McGill P, Toogood S, Allen D, Hughes JC, et al. (2013] Definition and scope for positive behavioural support. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support 3(2]: 14-23.

- Hieneman M, Dunlap G (2000] Factors Affecting the Outcomes of Community-Based Behavioral Support: Identification and Description of Factor Categories. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 2(3]: 161-178.

- Houchins DE, Jolivette K, Wessendorf S, McGlynn M, Nelson CM (2005] Stakeholders' view of implementing positive behavioral support in a juvenile justice setting. Education and Treatment of Children pp. 380-399.

- Inchley-Mort S, Hassiotis A (2014] Complex Behaviour Service: content analysis of stakeholder opinions. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities 8(4]: 228-236.

- Lohrmann S, Forman S, Martin S, Palmieri M (2008] Understanding school personnel's resistance to adopting schoolwide positive behavior support at a universal level of intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 10(4]: 256-269.

- Lohrmann S, Martin SD, Patil S (2012] External and internal coaches' perspectives about overcoming barriers to universal interventions. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 15(1]: 26-38.

- MIND for Better Mental Health (2013] Mental health crisis care: physical restraint in crisis a report on physical restraint in hospital settings in England. London, UK.

- MIND for Better Mental Health (2015] Restraint in Mental Health Services: What the Guidance Says. London, UK.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015] Violence and Aggression: Short-Term Management in Mental Health, Health and Community Settings. London, UK.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015] Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. Guidance No. NG11. London, UK.

- NHS England & Local Government Association (2014] Ensuring quality services: Core Principles Commissioning Tool for the development of Local Specifications for services supporting Children, Young People, Adults and Older People with Learning Disabilities and / or Autism who Display or are at Risk of Displaying Behaviour that Challenges. London, UK.This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.06.555690

- NHS Protect (2014] Meeting Needs and Reducing Distress-Guidance on the prevention and management of clinically related challenging behaviour in NHS Settings, UK.

- Noblit GW, Hare RD (1988] Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies Vol. 11.

- Porterfield J (1987) Positive Monitoring: Method of Supporting Staff and Improving Services for People with Learning Difficulties. Birmingham: British Institute of Learning Disabilities.

- Ring NA, Ritchie K, Mandava L, Jepson R (2011] A guide to synthesising qualitative research for researchers undertaking health technology assessments and systematic reviews. Edinburgh: NHS Quality Improvement Scotland.

- Royal College of Nursing (2013] Draft guidance on the minimisation of and alternatives to restrictive practices in health and adult social care, and special schools: Consultation. London, UK.

- Schutz A (1962] Concept and theory formation in the social sciences. In Collected Papers I pp. 48-66.

- Skills for Care & Skills for Health (2014] A Positive and Proactive Workforce: A Guide to Workforce Development for Commissioners and Employers Seeking to Minimise the Use of Restrictive Practices in Social Care and Health. Leeds and Bristol.

- (2013] Specialist Unit for Review Evidence (SURE] 2013 Questions to assist with the critical appraisal of systematic.

- Sugai G, Horner RH, Dunlap G, Hieneman M, Lewis TJ, et al. (2000] Applying positive behavior support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 2(3]: 131-143.

- Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, et al. (2014] Metaethnography 25 years on: challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC medical research methodology 14(1]: 80.

- Woolls S, Allen D, Jenkins R (2012] Implementing positive behavioural support in practice: the views of mediators and consultants. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support 2(2]: 42-54.