Impact of Reproductive Health Education Intervention On Reproductive Health Practice In Rural Literate Sarna Tribal Women

Deoshree Akhouri1* Suprakash Chaudhury2 and Meenakshi Akhourie3

1 Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharla! Nehru Medical College, India

2 Department of Psychiatry, Dr D Y Patil Medical College, India

3 Department of Home Science, Ranchi University, India

Submitted: August 08, 2017; Published: August 29, 2017

*Corresponding author: Suprakash Chaudhury, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Dr D. Y. Patil Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India; Email: suprakashch@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Deoshree A, Suprakash C, Meenakshi A. Impact of Reproductive Health Education Intervention On Reproductive Health Practice In Rural Literate Sarna Tribal Women. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017; 6(1): 555678. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.06.555678

Abstract

Background: Reproductive health education intervention is assuming increasing importance globally in the context of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Studies evaluating the impact of such intervention are sparse in India and none have been carried out in tribal population of Jharkhand.

Aim: To assess the impact of a reproductive health education intervention package on reproductive health practice in rural literate Sarna tribal women in Jharkhand.

Methods: The sample for the study consists of 180 literate Sarna tribal women divided into three groups; one control group and two experimental groups. After the baseline assessment the experimental groups were given reproductive health education through audio-visual materials presented with and without discussion using a pre and post intervention design.

Results: Results revealed that the educational intervention resulted in a significant improvement in reproductive Health practice of the participants. Reproductive Health Education imparted with discussion was significantly more effective as compared to Reproductive Health Education without such discussion for the improvement in Reproductive Health practice.

Conclusion: Educational intervention improved reproductive health practice. Reproductive health education based on discussion as compared to reproductive health education without such discussion is more effective for the improvement in reproductive health practice. Greater the frequency of intervention stronger the effects on reproductive health practice. Age does not influence the reproductive health practice of the respondents

Keywords: Reproductive health education; Reproductive health practice; Tribal women

Introduction

The recent economic growth in the Asian countries has resulted in a breakdown of traditional support systems such as the family because of rapid urbanization and modernization. Moreover, a large number of people are living below the poverty line in impoverished environment in urban and rural communities. Once a young woman is capable of having children, her mobility and opportunities may be restricted as family fears that she may be sexually victimized or have premarital sexual relations that would bring dishonour to the family. There is increasing prevalence of premarital sex, unwanted pregnancies, forced childbearing, STI's, STD's, HIV, and unsafe abortions in these regions that indicate a lack of knowledge about sexuality and reproductive health [1] Studies from Turkey, Iran, India and Malaysia reveal that sex related risky behavior s are increasing [1-5]. The problem is compounded in rural areas where lack of information, social stigma, and personal and cultural fears combined with inadequate health services, predisposes young people to poor knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding reproductive health [6]. Under these conditions, educating women benefits the society as a whole. It has a more significant impact on poverty and development than men's education. It is also the most influential factor in improving child health and reducing infant mortality.

Reproductive health has been defined as, "a state of complete physical, mental and social well being -not merely the absence of disease or infirmity but also-in all matters relating to the reproductive system and its junctions and processes" [7]. The problem of reproductive health has become an issue of grave concern for demographers, social scientists, activists and social reformers. Hassan et al. [8] has considered Reproductive health as 'a generic term covering a number of dimensions such as anatomy of reproductive organs, safe sex relation, safe motherhood and child survival, gynecological problems, reproductive rights, STD, HIV infections and AIDS. It is now recognized not only as an end in itself but also a major instrument of overall socio-cultural development and the creation of a new social order'. Despite their great need for accurate information, adolescents throughout the world have extremely limited access to reproductive health services. Teenagers have difficulty making use of the services even when they are available. There is often strong religious and political opposition to sexuality education out of fear that it will encourage sexual activity. Data indicate, however, that sexuality education does not encourage young people to engage in sex. Most studies show that education about reproductive and sexual health contributes to the postponement of sexual activity and to the use of contraception among teens that are sexually active [9-15].

There is a paucity of Indian studies on the attitude and knowledge about reproductive health of women particularly from rural areas. Researchers conducted on general health issues reveal that scientifically correct information, knowledge, healthy attitude and behavior about health related issues was very low [6,16-18] Adolescents and young adults learn about sexual matters and reproduction by observing adult behaviour, from peers and older siblings, increasingly from the media, and, in some families, from their parents. Such information, however, is typically limited, frequently erroneous and, in the case of the media, often unduly glamorized. Thus, formal instruction is an important source of accurate information. Formalized curricula for sexuality education are much less common in developing countries than in developed ones, and they are typically not implemented on a national level.

In many cases, the average period of school attendance is so short as to preclude this possibility. Even in countries with nearly universal secondary education, many of the most disadvantaged adolescents drop out of school prematurely. Thus, school-based programmers need to be supplemented by various community-based educational programmers. Especially now, when adolescents are increasingly at risk of STDs and AIDS, it is crucial that governments, educators, parents and community leaders recognize these risks and the reality of premarital sexual activity among young people. It is imperative to work together to provide the sex education to young people protect themselves. This includes, in addition to biological facts, information about dating, relationships, marriage and contraception. Programmers must help young people-boys and girls-recognize the merits of abstinence, develop the skills necessary to resist peer pressure and inappropriate sexual advances, and instill the confidence to negotiate the use of contraception with their partner.

Tribal communities are generally associated with a territory or a habitat, mostly in hilly and forest regions. The social and economic systems are simple, largely non-monetized. Many of them have their own language. They live in the state of poverty. Their access to health facility is very limited. They do not have scientifically correct information, knowledge, healthy attitude and behavior about health related issues [19]. The present study aimed at imparting reproductive health education to Sarna tribal females of Ranchi through audio-visual materials as an intervention package and to examine the difference, on the impact of educational materials presented with and without disc

Material and Methods

The study was carried out among the Sarna tribal’s in Kanke district of Jharkhand. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethical committee. All the subjects gave written informed consent.

Sample

The sample for the study consists of 180 literate Sarna tribal women who were selected on a stratified random basis from rural areas of Namkum and Kanke. The stratification is based on age. There were three age groups namely 15-19 yrs, 20-24 yrs and 25-29 yrs and for each age group 60 literate Sarna tribal women selected on random basis. The research design makes a comparison between two experimental groups and the control group. These 180 subjects are divided into three groups; one control group and two experimental groups. The sample design is given at Table 1.

Tools

The following tools were applied for the collection of data:

Socio-demographic and personal data sheet: It consists of ten questions to obtain personal information from the subjects on such theme as name, age, address, gender, education, religion, caste, marital status, tribal/non-tribal, education, monthly income and occupation of the parents.

Reproductive Health Practice Scale:It consists of 24 items. Overall 4 themes in this scale are Conception and Child Birth (6 items), Safe Motherhood (6 items), Fertility Regulation Method (6 items) and STD/AIDS (6 items). Each question has three alternative responses: Always, Never and Sometimes. Score 3, 2 and 1 was given for the alternatives. The range of scores was from 24-72. High scores indicate better practices related to Reproductive Health. The scale was developed by the P.G. Department of Psychology Ranchi University and was reported to have a high degree of reliability and validity [20].

Audio-Visual Reproductive Health Materials: It consists of colored/black & white photographs and messages. There are 40 photographs (26 cm x 20 cm) for reproductive health scale covering 5 themes and specific message. These photographs and messages depicted scientifically correct information and knowledge on reproductive health information, attitude and practice. The messages are recorded in audio cassette and communicated to the sample through tape recorder. The colored photographs are shown to the subjects one by one and the message related to each photograph is given simultaneously. It was not possible to have photograph regarding some themes of reproductive health, such as reproductive health organs, reproductive system and intimate relationship for such themes drawing suited to tribal figures were made and used for data collection.

Procedure

After explaining the aims of the study and assuring about confidentiality the subjects were included in the after obtaining written informed consent. Information about reproductive health practice was obtained from the control and the two experimental groups of literate Sarna tribal women. Initial data obtained from the control as well as the experimental groups was taken as the base line data. There was no intervention for the control group while the two experimental groups were exposed to audio-visual reproductive health educational materials. One experimental group received educational materials without discussion while the other experimental group received educational materials with discussion. After each intervention the reproductive health practice scale was applied to the subjects.

For both the experimental groups four interventions are made. There was a gap of ten days between the interventions. One of the experimental groups is just presented audio-visual educational materials whereas the other group not only received educational materials but was also exposed to discussion at each of the four interventions. If the intervention with and without discussion has any differential impact, it would be reflected in the differences between the scores of the two experimental groups.

Statistical Analysis

Apart from percentages the main statistical measures namely analysis of variance and t-test were applied for the analysis of data. The nature of data was such as 3 x 3 x 4 factorial design seemed to be appropriate for the analysis of variance. To examine the impact of intervention, age and frequency of intervention on Reproductive Health Practice ANOVA and t-test were used for the analysis of data. The Experimental Groups were compared separately with the control group and also the two Experimental groups were compared with each other on reproductive health practice. Comparison was made on the base line data as-well- as on each of the 4 interventions impact data. Furthermore the four interventions impact data were compared with each other for both the Experimental groups. Besides these comparison was also made between the age groups of reproductive health practice.

Results

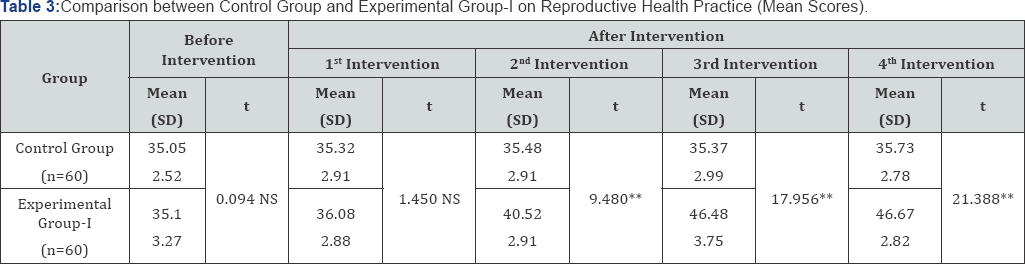

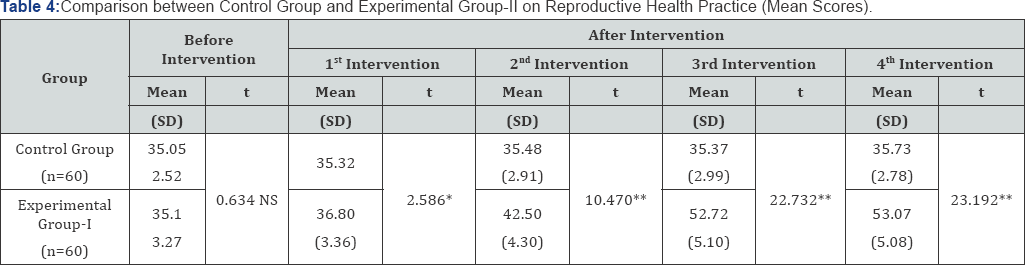

Analysis of variance (F-ratio) of Reproductive Health Practice Scores is given in Table 2. Using t-tests comparison was made between the mean reproductive health practice scores of the control group and the experimental groups. The mean and standard deviation scores of reproductive health practice for the control group and the experimental group-I along with t-ratios testing the significant of mean difference are reported in Table 3. Comparison between Control Group and Experimental Group- II on Reproductive Health Practice (Mean Scores) is given in Tables 4 & 5 indicates the comparison between Experimental Group-I and Experimental Group-II on Reproductive Health Practice (Mean Scores). Table 6 shows the comparison between Intervention Impact Mean Scores for Reproductive Health Practice in experimental group I and experimental group II. Comparison between the three Age Groups on Mean Scores for Reproductive Health Practice after each intervention is given in Table 7.

* = Significant at .05 level; ** = Significant at .01 level; NS = Not significant

* = Significant at .05 level; ** = Significant at .01 level; NS = Not significant

* = Significant at .05 level; ** = Significant at .01 level; NS = Not significant

Discussion

The present research is an intervention study. The main objective of the research is to evaluate the impact of Reproductive Health education on Reproductive Health Practice, using audio-visual educational materials. It is evident from Table 2 that the three groups namely the control group and the two experimental groups differ significantly on reproductive health practice scores. Age does not produce significant effect on reproductive health practice. The main effects of number of interventions are found to be highly significant statistically. This shows that educational interventions based on discussion produces stronger impact than the educational interventions without discussion. The interaction effects of group and age are statistically insignificant implying that the effect of intervention is the same for the three age groups.

The intervention effects of group and number of interventions are highly statistically significant, indicating that the effects of frequency of interventions are not the same for three groups. It may be recalled here that the subjects were divided into three groups, one being the control group and the two being the experimental groups. One of the experimental group received audio-visual educational materials followed by discussion of the message. Other experimental group was given only the message with visual materials with discussion. The result shows that the two experimental groups differ significantly from the control group and also the experimental groups differ from each other significantly in their reproductive health practice scores. The main intervention effects of age and number of intervention are not statistically significant. This indicates that the effects of number of interventions are not different for three age groups. The third order interaction effects group, age and number of interventions are not found to be statistically significant. This indicates that the effects of the combination of two factors namely group and number of intervention does not differ in magnitude from level to level third factor say age.

Interventions

It is evident from Table 3 that before intervention there was no significant difference between the control and experimental group-I on mean reproductive health practice scores. Even on 1st intervention impact data the control group and the experimental group-I did not seem to differ significantly. Statistically significant difference was found after 2nd, 3rd and 4th intervention impact data. (Table 3) It is observed that the mean reproductive health practice scores of the experimental group-I (40.52) are higher than the mean reproductive health practice scores of the control group (35.48). It indicates that the difference between the control and experimental group-I are found to be statistically significant at 0.01 levels. The control and the experimental group-I tend to be significantly different on the 3rd intervention impact data. The mean scores of control group was 35.37 while the experimental group-I was 46.48. The t-ratio was 17.956 which are statistically significant at .01 levels.

The control and the experimental group-I differ significantly in their mean reproductive health practice scores on the final and the 4th intervention impact data also. The mean reproductive health practice scores remained more or less statistic throughout the period of research. The range of scores for the control group was from 35.05 to 35.73. The mean reproductive health practice scores of the experimental group-I went on changing on response to number of interventions. Before intervention the mean score was 35.10 which changed to 46.67 after 4th intervention. The impact of interventions tends to be complete after 3rd intervention. This is evident from the fact that the mean reproductive health practice scores of the experimental group-I are more or less same the 3rd and the 4th intervention.

Table 4 compares the control group and experimental group- II on mean reproductive health practice scores using t-tests. The comparison has been made on base line data as-well-as on each of the four interventions impact data. In this table are given mean and standard deviation scores along with t-ratios testing the significance of mean differences. The table indicates the following main points. The difference between the control group and the experimental group-II was not significant on base line data. The mean reproductive health practice scores for the control group were 35.05 and the experimental group-II was 34.75 which are more or less same.

The experimental group-II does differ significantly from the control group on the 1st interventions impact data. The mean scores for the experimental group-II was 36.80 and the control group was 35.32 and t-ratio found to be 2.586 which is significant at .05 level. The mean reproductive health practice scores of experimental group-II further increased to 42.50 than control group from 35.48 after 2nd intervention impact data. The obtained t-value was 10.470 which are statistically significant at .01 levels. On the 3rd and 4th interventions impact data the mean reproductive health practice scores of experimental group-II were significantly higher than those of the control group. Though 1st interventions did produce changes in reproductive health practice but the change was moderate. But with 2nd intervention the change in the reproductive health practice scores of the experimental group-II was more prominent. It increased from 36.80 (1st intervention) to 42.50 (2nd intervention) which again increased to 53.07 after 4th intervention.

The interventions this produced change in the reproductive health practice which is amply demonstrated by the fact that the mean scores of the control group remained static throughout the period of the study while the mean score of experimental group- II went an improving till 4th educational intervention.

Not only was the comparison made between the control group and experimental groups but also between the two experimental groups. It may be started here that the two experimental groups differ in terms of the nature of interventions to which they were expose. The experimental group-I was given only messages related to photographs/drawings while experimental group-II was given message with discussion.

Table 5 compares the two experimental groups on there baseline data and on each of the four interventions impact data of reproductive health practice. The table shows the mean and standard deviation scores of reproductive health practice for the two groups along with t-ratios, examine the significance of mean difference.

The following main tendencies are noted. The data shows that there were no significant difference between the experimental group-I and experimental group-II on base line data on reproductive health practice. It indicates that before interventions the two groups did not differ at all in their reproductive health practice. On 1st intervention impact data the two groups did not seem to differ on reproductive health practice. Though the experimental group-I has shown improvement (in their reproductive health practice) but experimental group- II did not show much improvement in reproductive health practice in response to the 1st interventions. The mean of both the groups have respectively 36.08 and 26.80. Here the group having reproductive health education without discussion mean was greater than the group which had received education with discussion. The degree of improvement in both the groups is not the same. After 2nd intervention the two groups were found to differ significantly in their mean scores of reproductive health practice. It may be noted that the mean scores for experimental group-II which received educational materials with discussion was 42.50 and that of the experimental group-I which received educational materials without discussion was 40.52. The obtained t-value was 2.959, which was statistically significant.

On 3rd intervention impact data the mean reproductive health practice scores of the experimental group-II (52.72) was significantly much higher than that of the experimental group-I (46.48). The t-ratio was 7.629 which were found to be statistically significant at .01 levels. This indicates that the group which received educational materials based of discussion had better reproductive health practice than the group which received educational materials without discussion.

On the 4th intervention impact data the two groups were found to differ significantly. The mean reproductive health practice scores of the experimental group-I and experimental group-II were respectively 46.67 and 53.07. The ratio was 8.534 which are found to be statistically significant. Both the groups showed improvement immediately after 1st intervention. The difference in the rate of improvement between the two groups was noticed also 2nd intervention.

The rate of improvement in the experimental group-II which received educational materials with discussion was higher than the rate of improvement shown by the group which received educational materials without discussion.

Table 6 compares between the mean scores of the two interventions impact data using t-test. The comparison has been made separately for the experimental group-I and the experimental group-II. The 1st intervention impact data was compare with the 2nd, 3rd and 4th interventions impact data. Similarly 2nd intervention impact data was compared with 3rd and 4th intervention impact data and also a comparison was made between the 3rd and 4th intervention impact data.

The following main points may be noted in Table 6. In both the experimental groups mean reproductive health practice scores of intervention impact data 1st differed significantly from those of intervention impact data 2nd, 3rd and 4th. The magnitude of mean difference was found to increase in response to each of the subsequent intervention. The mean scores for 2nd intervention impact data are significant lower than those for 3rd and 4th intervention impact data. This was found not only in experimental group-I but also in experimental group-II. The rate of improvement in experimental group-II was higher than the rate of improvement in experimental group-I. There was no significant difference between the 3rd and 4th intervention impact data in experimental group-I. But in experimental group-II significant difference was found between the 3rd and 4th intervention, it indicates that intervention improved their reproductive health practice when education materials given with discussion.

Table 7 shows the mean scores of the three age groups in each of the control group experimental group-I and experimental group-II for reproductive health practice. The relationship of age with reproductive health practice was examined separately There were three age groups namely 15-19yrs, 20-24 yrs and 25- 29yrs. The comparison was made on base line data as-well-as on each of the four intervention impact data of reproductive health practice. On the whole 36 age comparison have been made. Mean reproductive health practice scores of the different pairs of the age groups along with t-ratios, examining the significant of mean difference are reported Table 7 which indicates the following main points: Age did not seem to influence the reproductive health practice scores of the subjects of the experimental group-I and the experimental group-II in different intervention impact data. Most of the t-ratios found to be statistically insignificant. This indicates that age of the respondents does not seem to be associated with reproductive health practice.

Limitations

As the present study is experimental social research, the size of the sample for the study is small. Only 180 literate Sarna tribal women were the subjects of the study. The size of the sample could have made the picture more vivid and comprehensive. The size of the sample however could not be increased because data from all the three groups (Control and two experimental groups) were collected on five themes with regular intervals of 10 days. The study was confined to the tribal population and the differences within the tribal population in respect to religion (Sarna, Christianity), ethnicity (Oraon, Munda), were not taken into account, probably on the empirical evidences that the tribals irrespective of their differences in religion and ethnicity were lacking proper reproductive health information, attitude and practice. Only literate Sarna was taken for the study and because of this study does not indicate the condition of illiterate tribal women and efficacy of this study. Study on illiterate Sarna tribal women needs to be conducted. The study was confined to the three age groups (15-19yrs, 20-24yrs, and 25-29yrs) Sarna tribal women only. The findings of this research may not be generalized to the other age groups of the tribal population.

Conclusion

Educational intervention improved reproductive health practice of tribal women. Reproductive health education based on discussion as compared to reproductive health education without such discussion is more effective for the improvement in reproductive health practice. Greater the frequency of intervention stronger the effects on reproductive health practice. Age does not influence the reproductive health practice of the respondents.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the guidance and assistance of Dr M.K. Hassan, Retired Professor, Dept of Psychology and Ranchi University.

References

- Mustapa MC, Ismail KH, Mohamad MS, Ibrahim F (2015) Knowledge on Sexuality and Reproductive Health of Malaysian Adolescents-A Short Review. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 211: 221-225.

- Sahin NH (2008) Male university students' views, attitudes and behaviors towards family planning and emergency contraception in Turkey. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 34(3): 392398.

- Simbar M, Tehrani FR, Hashemi Z (2005) Reproductive health knowledge, attitudes and practices of Iranian college students. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 11: 888-897.

- Rangaiyan G (1996) Sexuality & sexual behaviour in the age of AIDS: A study among college youth in Mumbai [Ph.D. dissertation], International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India.

- Sharma AK, Sehgal VN (1998) Knowledge, attitude, belief and practice study on AIDS among senior secondary students. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology 64(6): 266-269.

- Meena JK, Verma A, Kishore J, Ingle GK (2015) Sexual and Reproductive Health: Knowledge, Attitude, and Perceptions among Young Unmarried Male Residents of Delhi. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2015: Article ID 431460, 6 pages.

- United Nations Fund for Population Activities (1996) Programme Review and Strategy Development, India. UNFPA. Voluntary Health Services. AIDS Prevention and Control Project: HIV Risk Behaviour in Tamilnadu: Sentinel Surveillance Survey. Report on Baseline Wave- 1 996.Chennai, India.

- Hassan MK, Jayaswal M, Hassan P (2001) Reproductive health awareness in female students: Role of religion and education. Indian Journal of Psychological Issues 9(2): 67-75.

- Basnayake S (1993) Starting a programme in Sri Lanka. Plan Parent Chall 2: 43-45.

- Gulmezoglu AM, Langer A, Piaggio G, Lumbiganon P, Villar J, et al. (2007) Cluster randomised trial of an active, multifaceted educational intervention based on the WHO Reproductive Health Library to improve obstetric practices. BJOG 114(1): 16-23.

- Mba CI, Obi SN, Ozumba BC (2007) The impact of health education on reproductive health knowledge among adolescents in a rural Nigerian community. J Obstet Gynaecol 27(5): 513-517.

- Obasi AI, Cleophas B, Ross DA, Chima KL, Mmassy G, et al. (2006) Rationale and design of the MEMA kwa Vijana adolescent sexual and reproductive health intervention in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. AIDS Care 18 (4): 311-22.

- Rao RSP, Lena A, Nair NS, Kamath V, Kamath A (2008) Effectiveness of reproductive health education among rural adolescent girls: A school based intervention study in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka. Indian J Med Sci 62(11): 439-43.

- Tork HM, Al Hosis KF (2015) Effects of reproductive Health Education on Knowledge and Attitudes among female adolescents in Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Res 23(3): 236-242.

- Zhang T, Wu YQ, Wang YP, Zhao GL, Yin F, et al. (2003) Effects of a comprehensive health education program on reproductive tract infections/sexually transmitted diseases intervention among reproductive age population in the rural areas of China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 24(10): 908-912.

- Sahay M (1996) Health status of tribal women in India. In: Status of tribals in India (Eds.). Amar Kumar Singh and MK Jabbi, Har- Anand Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Singh AK, Jayaswal M (1996) Health modernity in the tribals of Jharkhand, Bihar. In: Status of tribals in India. Eds. Amar Kumar Singh and MK Jabbi, Har-Anand Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Parwej S, Kumar R, Walia I, Aggarwal AK (2005) Reproductive health education intervention trial. Indian J Pediatr 72(4): 287-91.

- Kumar R, Singh MM, Kaur A, Kaur M (1995) Reproductive health behaviour of rural women. J Indian Med Assoc 93: 129-131.

- Hassan MK (2002) Reproductive Health Awareness and Education in Rural Tribal Women: An Intervention Study. UGC research project. P.G. Department of Psychology Ranchi University, India.