Exploring Associations Between Adult Attachment Patterns, Time Spent Unemployed and Use of Substances to Regulate Affect Among Australian Job Seekers

Dragana Krpalek*, Pamela Meredith and Jenny Ziviani

Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Queensland, Australia

Submission: May 30, 2017; Published: June 29, 2017

*Corresponding author: Dragana Krpalek, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Queensland, 11455 Aster Street, Loma Linda 92354, USA, Tel: 9095584628; Email: dkrpalek@llu.edu

How to cite this article: Dragana K, Pamela M, Jenny Z. Exploring Associations Between Adult Attachment Patterns, Time Spent Unemployed and Use of Substances to Regulate Affect Among Australian Job Seekers. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2017; 4(3) : 555639. DOI:10.19080/PBSIJ.MS.ID.555639

Abstract

Experiencing unemployment increases individuals' risk of substance use, however, little is known about personal characteristics that may increase or decrease the vulnerability of unemployed adults to this use. Therefore, the present study draws on attachment theory to explore associations between attachment patterns and substance use amongst unemployed job seekers. Ninety-five unemployed adults accessing an employment support service in Australia completed the Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ), the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ), and a questionnaire about frequency of emotional eating, smoking, and use of alcohol and illicit drugs. The majority of participants (71.6%) reported an insecure attachment style. Results revealed that attachment security was inversely associated with substance use, while both attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety were positively associated with substance use. Further, adult attachment patterns moderated associations between unemployment time and drug use. Together, findings offer new insights into the associations between attachment patterns, time spent unemployed and substance use. Implications for provision of services are discussed.

Keywords: Attachment theory, unemployment, job seeking, substance use

Abbreviations: ASQ: Attachment Style Questionnaire; RQ: Relationship Questionnaire; IWM: Internal Working Models; SRJA: Sarina Russo Job Access

Introduction

Mounting empirical data over the past three decades has revealed that unemployment, specifically long-term unemployment, can be a precursor to psychosocial, emotional, and physical health problems, and can amplify pre-existing health conditions [1-4]. Additionally, unemployment has been linked with social isolation, family breakdown, a sense of lost purpose in life, poverty, and suicide [5-7]. Understandably, unemployment is often experienced as a distressing life event. [8] , necessitating the activation of one's coping strategies.

Unemployment and Coping Strategies

In broad terms, coping strategies can be classified as either adaptive or maladaptive. Adaptive coping strategies include problem-focused, support-seeking, and positive reframing approaches, all with the common goal of targeting the problem at hand and enlisting constructive supports in a timely manner [9]. Alternatively, maladaptive coping strategies may include denial, self-blame, avoidance, and substance use. These strategies tend to simultaneously mask and exacerbate underlying problems [9]. Of note, significant bi-directional relationships between unemployment and maladaptive forms of coping have been reported, drawing particular attention to use of external affect regulators [2,10-12]. External affect regulators are defined as substances which regulate dysphoric affect by exerting a soothing, distracting, or exciting influence, but are also known risk factors for disease [13]. External affect regulators include, but are not limited to, emotional eating, smoking, drinking alcohol, and using illicit drugs [13].

In a review of over 130 research papers, [2] noted that, while there is ample evidence that unemployment increases an individual's risk of external affect regulator use, little is known about personal characteristics that may increase or decrease the vulnerability of unemployed adults to this use. To this end, the present paper considers attachment theory as a means of delineating personal characteristics that are associated with increased use of external affect regulators among unemployed

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory, a highly validated theory of human development, proposes that it is possible to distinguish the way individuals establish relationships and respond to stressful situations based on their early experiences with their primary caregivers [14]. Specifically, advanced the view that all humans are born with an attachment system: an innate proximity- seeking behavioral system. When exposed to a stressor, infants' attachment systems become activated and they use attachment behaviors (e.g., crying) to signal their need for support. Ideally, caregivers will respond promptly, and satisfy infants' needs appropriately [14]. In the presence of an attuned caregiver, a safe haven, negative feelings recede, regulated physiological states are restored, and the attachment system is deactivated [14]. It is theorized that early attachment experiences with caregivers become internalized, and form internal working models (IWM), which are drawn upon when facing subsequent life challenges [14,15].

Adult attachment classifications are most often based on two underlying dimensions: attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety [16]. Broadly, adults with high levels of attachment avoidance or attachment anxiety are classified as insecurely attached, while adults with low ratings on both dimensions are considered securely attached. More specifically, adults with high attachment avoidance (also labeled dismissing attachment) hold positive IWMs of self and negative IWMs of others [16].

That is, they generally feel confident in their own abilities and have high self-esteem, while having limited expectations that others will be available for them when needed. Consequently, adults with avoidant attachment patterns employ coping strategies that involve distancing, diverting, and distracting themselves from stressors, referred to as 'deactivating strategies' [9] . In contrast, adults with high attachment anxiety (also referred to as preoccupied attachment) have negative IWMs of self and positive IWMs of others, translating into low levels of self-confidence and overdependence on others for feelings of self-worth [16]. Thus, anxiously attached adults tend to employ 'hyper-activating' strategies in order to maximize their chances of securing support, and these are typified by worry, rumination, and an excessive focus on negative emotions [9].

Adults with high levels of both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (also labeled fearful attachment) tend to simultaneously employ both deactivating and hyper-activating strategies [16]. As a result of this disorganized approach to coping, evidence demonstrates that adults with fearful attachment patterns are particularly prone to experiencing distress and burnout [17]. In contrast, adults with secure attachment patterns have positive IWMs of both self and others. Securely attached adults are thus comfortable with both autonomy and closeness [16]. Additionally, empirical evidence shows that attachment security is associated with greater resilience and development

Adult Attachment Patterns and Use of External Affect Regulators

According to attachment theory, insecurely attached adults are more likely to resort to external means, such as use of substances, to regulate affect due to their compromised internal emotional regulation systems [13]. For adults with high levels of attachment avoidance, use of external affect regulators may serve as an effective deactivating strategy, while for adults with high levels of attachment anxiety, external substances may aid in obtaining relief from heightened negative emotional states, especially upon failure to attain desired levels of social support. Consistent with this proposition, there is some evidence that both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance are positively associated, and attachment security is negatively associated, with emotional eating, smoking, and alcohol and drug use [19,20] [21]. However, there is presently no evidence of these associations specifically among people who are unemployed and seeking work.

The Present Study

As unemployment and job searching can often be distressing experiences. [8], they are likely to be associated with activation of the attachment system. Further, as activation of the attachment system suggests specific behavioral, emotional, and cognitive responses [14], this activation may manifest in coping strategies that are either adaptive or maladaptive. Being able to identify job seekers at heightened risk of external affect regulator use may support implementation of intervention strategies and inform the development of tailored intervention approaches.

Methods

Procedure

The Sarina Russo Group is a large training and employment agency in Australia and Great Britain. Sarina Russo Job Access (SRJA), one branch of the group, supports adults who are looking for work. Participants for the present study were sought from one office located in a metropolitan area in Queensland, Australia. The primary researcher was present at the SRJA office for the duration of one week. All job seekers who entered the SRJA office during this time were approached by the primary researcher and invited to participate in the study. Job seekers were asked to read a participant information sheet and sign a consent form prior to completing a survey. Participants were informed that their completed surveys would remain anonymous and be stored separately to their signed consent forms. Ethical clearance was granted by the Behavioral and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee of The University of Queensland (No. 2009000487). Gatekeeper clearance was provided by the Sarina Russo Group.

Participants

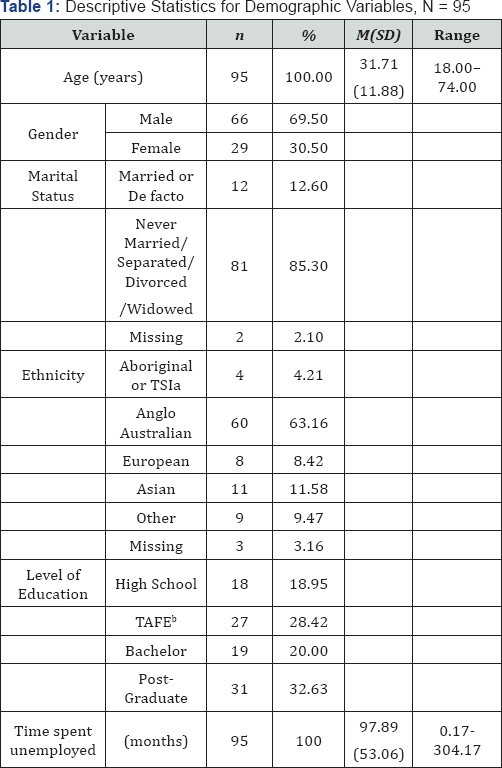

Note. aTSI = Torres Strait Islander. bTAFE = Technical and Further Education.

One hundred and nineteen adults were invited to participate in this study. Job seekers who were over the age of 18, currently unemployed, and utilizing SRJA services met the inclusion criteria for participating in the study. There were no exclusion criteria. Of the 119 people invited to participate in the study, 13 declined and nine did not qualify as they were currently employed. A further two participants were subsequently removed from the dataset due to a high number of missing responses. Thus, of the 119 adults who were invited to participate, 95 were included in the present study sample, representing a participation rate of 80%. The mean age of participants was 31.71 years, with a standard deviation of 11.88. The majority of participants were male, with an Anglo-Australian background. Demographic information of participants is summarized in (Table 1).

Measures

A cross-sectional study design was employed whereby participants completed a survey consisting of demographic questions, attachment questionnaires, and items regarding use of external affect regulators.

Demographic questions: Participants were asked to provide some demographic information including age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, and level of education. Additionally, participants were asked to estimate how long they had been unemployed in total (past and present unemployment time combined).

Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ): The ASQ was developed by Feeney, [22] for the purpose of assessing general attachment patterns of both adolescents and adults who are, or have been, in a romantic relationship, as well as those who have no romantic relationship experience. The ASQ is a selfadministered questionnaire and comprises 40 items. Each item consists of a statement about an individual's general perception about him/herself or others. Respondents rate how much they agree or disagree with the statement on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, to 6 = totally agree). Scores can be aggregated onto either two or five scales. The two-factor solution includes attachment avoidance (16 items) and attachment anxiety (13 items) scales. An example item for attachment avoidance is: 'I prefer to depend on myself rather than other people', and for attachment anxiety: 'It’s important to me that others like me'.

The five-factor solution includes an attachment security scale (eight items), two attachment avoidance subscales, and two attachment anxiety subscales. An example item for measuring attachment security is 'I feel confident about relating to others'. In the present study, overarching attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety scales, together with the attachment security scale, were employed.

Adequate internal consistency, construct validity, and convergent validity have been reported for the ASQ [22]. For the present study, alpha coefficient scores for the ASQ scales were .77, .73, and .83 for attachment security, attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety, respectively.

Relationship Questionnaire (RQ): The RQ is a brief, selfadministered questionnaire; comprising four items [16]. Each item describes one of four attachment styles: secure, fearful, preoccupied, or dismissing. Respondents choose one of the four items that best defines their personal style of relating to others. The RQ is simple to administer and has good predictive validity, convergent validity, and test-retest reliability [23]. The RQ has been used extensively in research to investigate attachment representations among adult samples [23]; therefore, the categorical RQ measure was employed in the present study to evaluate the representation of attachment styles across the study sample.

Use of External Affect Regulators Questionnair: This questionnaire was based on [13] 'Model of Hypothesized Mechanisms by which Attachment Security could contribute to Disease'. It is comprised of four categorical items, with each question addressing one external affect regulator: emotional eating, alcohol use, smoking, and drug use. Participants rate, on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Never, 1 = Seldom, 2 = Often, and 3 = Very Often), how often they use each external affect regulator in response to feeling emotionally upset, depressed, discouraged or anxious. Self-report measures of external affect regulator use have been described as comparatively less invasive than other methods, such as interview and observation. [24]. Further, no detectable systematic trends for respondents to either under- or over-estimate their use of external affect regulators on selfreport measures have been documented. (1992).

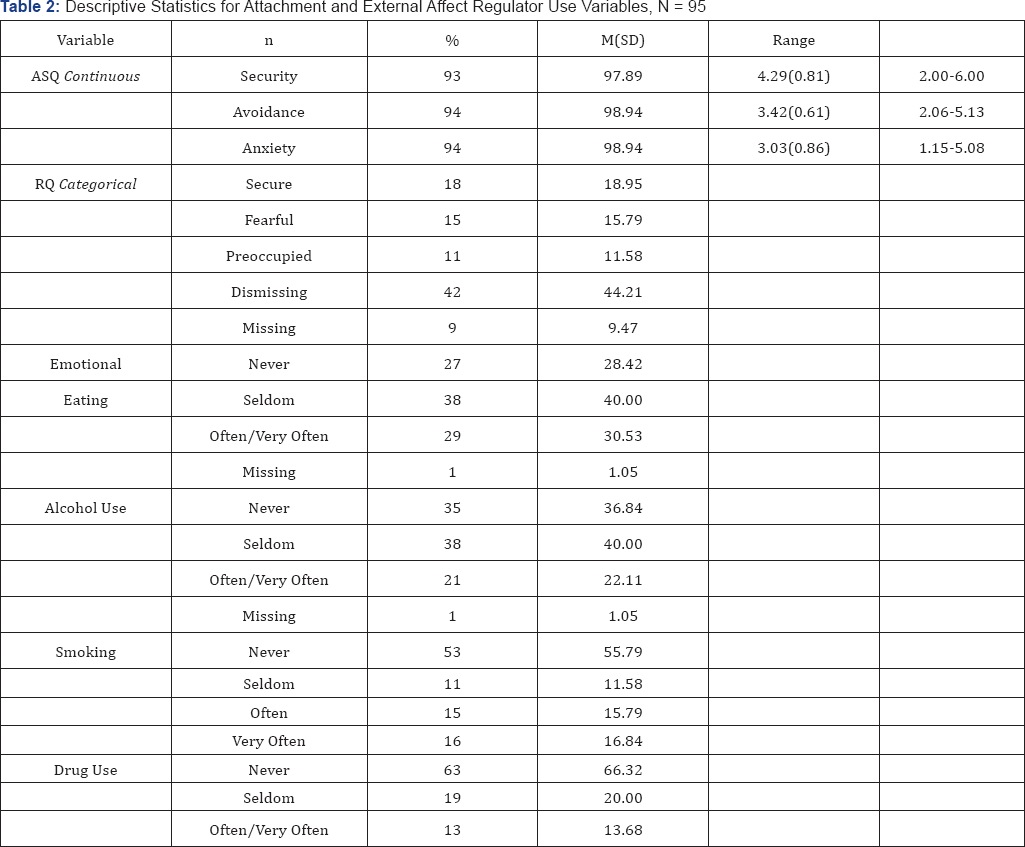

Statistical Analysis: Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20.0. All continuous variables, except for total unemployment time, were normally distributed and thus suitable for parametric testing. A logarithmic transformation was applied which successfully corrected the skewed total unemployment time variable. Additionally, categorical variables with less than 10% of cases in some categories were collapsed in order to reduce the risk of a Type II error. Thus, three variables required adjustment: emotional eating, alcohol use, and drug use (Table 2).

Relationships amongst continuous variables were investigated using Pearson's correlation analysis. Additionally, a series of analyses were conducted between demographic and all other variables in order to select covariate variables. Selected categorical covariates were then dummy coded in preparation for hypotheses testing.

A series of ordinal logistic regression models were applied to the data to explore relationships between attachment patterns and external affect regulator use. Further, moderation analyses were applied to test whether or not adult attachment patterns moderated relationships between unemployment time and use of external affect regulators. Moderation analysis involved computing a standardized total unemployment time variable, a standardized attachment variable, and a corresponding interaction variable within an ordinal logistic regression model [24]. Models revealing significant results were displayed graphically using Modgraph [25].

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Attachment security was negatively correlated with unemployment time (r = -.48, p <.001), while attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety were positively correlated with unemployment time (r = .44, p < .001 and, r = .37, p <.001, respectively). Additionally, age was positively correlated with attachment avoidance (r = .27, p <.01) and unemployment time (r = .35, p <.001).

Preliminary analyses further revealed that males reported higher levels of attachment avoidance (M = 3.54, SD = .62) in comparison to females (M = 3.15, SD = .47; F (1, 92) = 9.41, p <.01). Males also reported significantly more unemployment time (M = 37.27, SD = 61.67) in comparison to females (M = 14.34, SD = 16.74; F (1, 91) = 5.04, p < .05). Additionally, those who were married or in a de facto relationship reported lower rates of emotional eating in comparison to those who were never married, separated, divorced, or widowed (x2(2) = 6.53, p < .05). Lastly, education level was significantly associated with both unemployment time (F (3, 89) = 3.51, p < .05) and drug use (x2 (6) = 18.97, p <.01). Those who held a post-graduate degree reported less unemployment time (M = 21.14, SD = 54.66) in comparison to school graduates (M = 56.18, SD = 71.67), and less drug use in comparison to those in all other education groups. In consideration of the associations listed above, age, gender, marital status, and education level were included as covariates in further analyses.

Representation of Attachment Styles

According to the RQ categorical measure, 18.95% of participants reported a secure attachment style while 71.58% reported an insecure attachment style (Table 2).

Unemployment Time and Use of External Affect Regulators

Results showed that unemployment time was significantly associated with both alcohol use and but not with emotional eating or drug use. Significant findings are detailed below.

Alcohol Use: While the overall model for unemployment time and alcohol use did not reach significance (x2 (7) = 9.57, p > .05, Cox and Snell = .10), unemployment time was significantly positively associated with alcohol use. A one-unit increase in unemployment time was associated with a .80 increase in the log odds of alcohol use.

Smoking: Unemployment time was significantly associated with reported smoking levels (x2 (7) = 18.56, p < .05, Cox and Snell = .19). A one-unit increase in unemployment time was associated with a 1.22 increase in the log odds of smoking.

Adult Attachment Patterns and External Affect Regulator Use

Ordinal logistic regression analyses revealed that continuous ASQ attachment scales were significantly associated with both smoking and drug use, but not with emotional eating or alcohol use. Significant results are discussed below.

Smoking. Significant models were detected between smoking and all three attachment variables: attachment security (x2 (7) = 20.81, p < .01, Cox and Snell = .20), attachment avoidance (x2 (7) = 14.46, p <.05, Cox and Snell = .15), and attachment anxiety (x2 (7) = 26.81, p < .001, Cox and Snell = .25). A one-unit increase in attachment security was associated with a .93 decrease in the log odds of smoking. In contrast, a one- unit increase in attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety was associated with a .81 and 1.19 increase in the log odds of smoking, respectively.

Drug Use. Similarly, significant models were detected between drug use and each of the attachment variables: attachment security (x2 (7) = 30.22, p < .001, Cox and Snell = .28), attachment avoidance (x2 (7) = 29.63, p < .001, Cox and Snell = .28), and attachment anxiety (x2 (7) = 40.35, p < .001, Cox and Snell = .36). A one-unit increase in attachment security was associated with a .61 decrease in the log odds of drug use. Conversely, a one-unit increase in attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety was associated with a .86 and 1.29 increase in the log odds of drug use, respectively.

Adult Attachment Moderated Effects

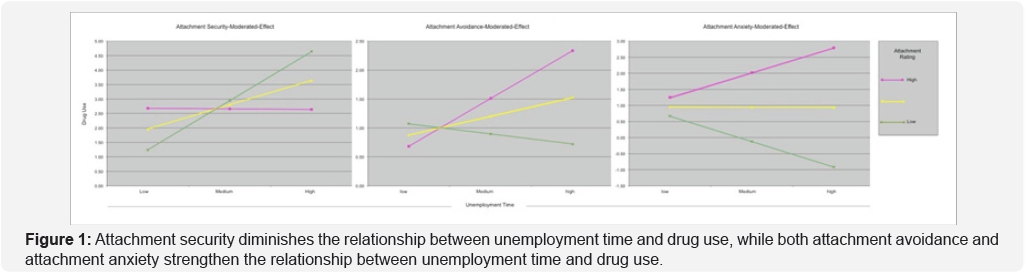

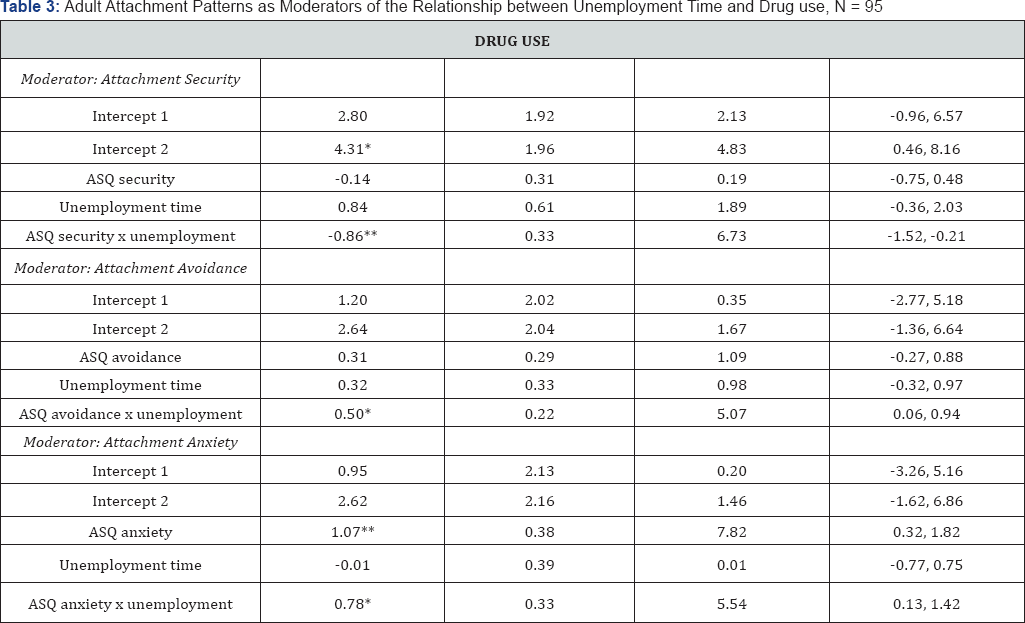

Ordinal logistic regression models were applied to test for attachment-moderated effects between the continuous unemployment time variable and categorical external affect regulator use variables. Significant models were detected for drug use. but not for extarnal effect regulators.

Note: Age, gender, marital status and education level were included as covariates in all analyses. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Attachment security emerged as a significant moderator between unemployment time and reported levels of drug use (x2 (9) = 38.58, p < .001, Cox and Snell = .35). As attachment security increased, the association between unemployment time and drug use lessened (Figure 1). A significant moderated effect was also indicated for attachment avoidance (x2 (9) = 34.24, p <.001, Cox and Snell = .32). As attachment avoidance increased, unemployment time became more strongly associated with drug use. Similarly, attachment anxiety was a significant moderator between unemployment time and drug use (x2 (9) = 45.66, p <.001, Cox and Snell = .40). As attachment anxiety increased, the association between unemployment time and drug use strengthened (Figure 1), (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study drew on attachment theory in an attempt to identify unemployed job seekers who were more, or less, vulnerable for external affect regulator use. Results of the present study extend the present literature, suggesting that job seekers with insecure attachment patterns are more likely, while securely attached job seekers are less likely, to smoke and use drugs as a means of coping. Additionally, findings underscored adult attachment patterns as significant moderators between times spent unemployed and drug use. Implications of these findings are discussed below.

Attachment Representation across a Sample of Job Seekers

Based on the RQ, the percentage of securely attached adults in the present study was much smaller than is typically reported in large, nationally representative samples. More specifically, only 18.95 per cent of the participants in the present sample reported a secure attachment style in comparison to approximately 60 per cent commonly reported among adult samples [15,26,27]. Further, approximately 44 per cent of the participants in the present study reported a dismissing (avoidant) attachment style compared to 25 per cent typically reported in the large studies cited above. [15] theorized that workers with avoidant attachment patterns feel vulnerable when not working and seek employment as a way of diverting attention from their unmet attachment needs. Individuals with a dismissing attachment style may therefore seek employment with urgency and persistence, potentially accounting for the higher representation of dismissing attachment in this job seeker sample. Further, adults with dismissing attachment styles have been found to change employers more frequently to avoid forming close working relationships [28]. Therefore, it follows that these adults may seek new employment opportunities more readily in comparison to securely attached adults, and consequently be over-represented in samples accessing employment support services. The small representation of securely attached job seekers and over-representation of insecurely attached job seekers may further indicate that: a) securely attached individuals are less likely to be unemployed, b) securely attached individuals are more likely to find work independently, without requiring employment support services, and/or c) exposure to stressful life circumstances such as unemployment, may magnify insecure responses [29].

Unemployment Time and External Affect Regulator Use

Unemployment time was significantly positively associated with use of tobacco and alcohol for affect regulation, but not with use of food or illicit drugs. Significant associations detected between unemployment time and both smoking and alcohol use in the present study are consistent with previous research findings (see Henkel, 2011, for an in depth review of the literature in this field). Further, while time spent unemployed was not significantly associated with drug use, subsequent analyses revealed significant attachment-moderated relationships between these variables (see 'Moderating Effects of Adult Attachment Patterns' below).

Attachment and Use of External Affect Regulators

Results revealed that job seekers with secure attachment patterns reported less smoking and drug use, while those with both avoidant and anxious attachment patterns reported higher levels of smoking and drug use. These results are in line with previous research which has demonstrated that high attachment security is associated with a low risk of substance use, while high attachment insecurity is associated with increased vulnerability [19, 20,30,31]. The present study is the first to demonstrate these trends among job seekers who are unemployed.

Contrary to expectation, however, adult attachment patterns were not significantly associated with emotional eating or alcohol use. Taken together, clear distinctions emerged between securely and insecurely attached job seekers in relation to their patterns of smoking and illicit drug use, but not in their use of food and alcohol. Reasons for this unexpected result are not clear, and may reflect sampling bias; further research regarding these relationships is recommended.

Moderating Effects of Adult Attachment Patterns

Results revealed that attachment security significantly moderated the relationship between unemployment time and drug use: increasing levels of attachment security were associated with a diminished relationship between unemployed time and drug use. In contrast, as attachment avoidance or attachment anxiety levels increased, the association between unemployed time and drug use strengthened. While previous studies have indicated that unemployment time is directly associated with increased drug use [32] [2], findings of the present study suggest that this association may be better understood through consideration of job seekers' attachment characteristics. As indicated by the data, insecurely attached job seekers are likely to be at high risk of drug use with increasing unemployment time, while job seekers with high attachment security may be at low risk of drug use.

Clinical Implications of Research Findings: Findings of the present study indicate the potential value of considering attachment-informed approaches in the provision of employment support strategies. Of note, findings suggest that insecurely attached job seekers are most likely to require input for reducing levels of tobacco and illicit drug use. It is further proposed that identification of job seekers’ individual attachment characteristics may support detection of those most vulnerable and prompt early implementation of such supports.

Substance use prevention programs typically include provision of information about the 'stress-cycle'; risks associated with substance abuse, and suggested alternate adaptive coping strategies [33, 34]. Assisting job seekers to understand their individual attachment patterns may further empower them to understand vulnerabilities associated with their attachment orientation. By gaining greater insight into their attachment- related vulnerabilities, job seekers may more effectively develop adaptive strategies for managing stressors related to unemployment and job seeking. Further, these insights and strategies may serve to support employment longevity in future employment.

Given that the majority of participants in the present study reported an insecure attachment style, adopting an attachment perspective may aid employment support counselors in selecting appropriate interventions and tailoring supports to meet job seekers' individual attachment-related needs. For example, identifying high levels of attachment avoidance may indicate the importance of providing distant forms of support (e.g., via email), and supporting needs for autonomy and independence [35] . In contrast, noting high levels of attachment anxiety may signify the importance of scheduling frequent appointments and providing face-to-face support [35].

Considerations and Recommendations for Future Research

The exploratory nature of this study introduces a number of limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents consideration of causal relationships. It is recommended that future studies employ a longitudinal design to investigate associations between adult attachment patterns and substance use over time (i.e., from acute to long-term unemployment). Second, all data were collected using self-report measures. Future research might augment self-report information with objective data such as that gathered from employment support agencies e.g., records of unemployment time. Third, the results of this study should not be generalized to other unemployed groups due to the relatively small sample size that was drawn from one agency in one Australian capital city. Fourth, although the brevity of the questionnaire used in the present study was beneficial in that it reduced participant burden and contributed to a high response rate, it may also have contributed to an increased Type II error rate. Lastly, the response items of the external affect regulator use questionnaire employed in the present study (i.e., never, seldom, often, or very often), were open to subjective interpretation and resulted in limited ability to distinguish between levels of use. Future investigations may consider use of a standardized measure of external affect regulation, such as the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test [36] . Despite these limitations, findings were largely consistent with theoretical expectations [37, 38].

Conclusion

This study was the first to investigate attachment representations among unemployed job seekers and to explore the ways in which job seekers' attachment characteristics relate to their tendency of using external affect regulators. On the whole, findings suggest that attachment security is negatively associated, and attachment insecurity positively associated, with external affect regulator use among unemployed job seekers, namely smoking and illicit drug use. These results underline the value of undertaking further research in this field, with a view to adopting an attachment perspective to enhance present employment support and intervention strategies for unemployed job seekers.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank administrative staff from the Sarina Russo Group for opening their doors and permitting the collection of valuable data for this research project. The authors also gratefully acknowledge clients of the Sarina Russo Group without whose participation this project would not have been possible.

References

- Creed P (1999) Predisposing factors and consequences of occupational status for long-term unemployed youth a longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescenc 22(1): 81-93.

- Henkel D (2011) Unemployment and substance abuse: a review of the literature (1990-2010) Current Drug Abuse Reviews 4(1): 4-27

- Kessler RC, House JS, Turner JB (1987) Unemployment and health in a community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 28(1): 5159.

- Mc Kee-Ryan, FM, Kinicki AJ, Song Z, Wanberg CR (2005) Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study Journal of Applied Psychology 90(1): 53-76.

- Gallie D, Paugam S, Jacobs S (2003) Unemployment, poverty and social isolation: Is there a vicious circle of social exclusion? European Societies 5(1): 1-32.

- Larson JH (1984) The Effect of Husband's Unemployment on Marital and Family Relations in Blue-Collar Families. Family Relations 33(4): 503.

- Kieselbach T (2003) Long-Term Unemployment among Young People: The Risk of Social Exclusion. American Journal of Community Psychology 32(1): 69-76.

- Smari J, Arason E, Hafsteinsson H, Ingimarsson S (1997) Unemployment, coping and psychological distress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 38(2): 151-156.

- Mikulincer M, Florian V (2004) Attachment style and affect regulation: Implications for coping with stress and mental health. In MB Brewer, M Hewstone (Edn) Applied Social Psychology, Blackwell Publishing, Malden, USA.

- Laitinen J, Ek E, Sovio U (2002) Stress-related eating and drinking behavior and body mass index and predictors of this behavior. Preventive Medicine 34(1): 29-39.

- Martin CR (2008) Identification and treatment of alcohol dependency. M & K Update Ltd publisher, Cumbria, England.

- Vogli RD, Santinello M (2005) Unemployment and smoking: Does psychosocial stress matter? Tobacco Control 14(6): 389-395.

- Maunder RG, Hunter JJ (2001) Attachment and psychosomatic medicine: Developmental contributions to stress and disease. Psychosomatic Medicine 63(4): 556-567.

- Bowlby J (1988) A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development.

- Hazan C, Shaver PR (1990) Love and work: An attachment-theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5(9): 270280.

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM (1991) Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61(2): 226-244.

- Pines AM (2004) Adult attachment styles and their relationship to burnout: A preliminary, cross-cultural investigation. Work & Stress 18(1): 66-80.

- Hardy GE, Barkham M (1994) the relationship between interpersonal attachment styles and work difficulties. Human Relations 47(3): 263281.

- Caspers KM, Yucuis R, Troutman B, Spinks R (2006) Attachment as an organizer of behavior: implications for substance abuse problems and willingness to seek treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 1(32).

- Levitan RD, Atkinson L, Pedersen R, Buis, T, Kennedy SH, et al. (2009) A novel examination of atypical major depressive disorder based on attachment theory. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 70(6): 879-887.

- Brennan KA, Shaver PR (1995) Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

- Feeney JA, Noller P, Hanrahan M (1994) Assessing adult attachment. In MB Sperling, WH Berman (Edn) Attachment in adults: Clinical and developmental perspectives Guilford press, New York, USA. pp. 128152.

- Scharfe E, Bartholomew K (1994) Reliability and stability of adult attachment patterns. Personal Relationships 1: 23-43.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(6): 1173-1182.

- Jose PE (2008) ModGraph-I: A programme to compute cell means for the graphical display of moderational analyses: The internet version, Version Beta. Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR (1997) Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73(5): 1092-1106.

- Schirmer LL, Lopez FG (2001) Probing the social support and work strain relationship among adult workers: Contributions of adult attachment orientations. Journal of Vocational Behavior 59(1): 17-33.

- Feldman DC, Ng, TWH (2008) Careers: Mobility, Embeddedness, and Success. Journal of Management 33(3): 350-377.

- Cozzarelli C, Karafa JA, Collins NL, Tagler MJ (2003) Stability and change in adult attachment styles: Associations with personal vulnerabilities, life events, and global construals of self and others. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 22(3): 315-346.

- Kassel JD, Wardle M, Roberts JE (2007) Adult attachment security and college student substance use. Addictive Behaviors 32(6): 1164-1176.

- Schindler A, Thomasius R, Sack P, Gemeinhardt B, Stner U, et al. (2005) Attachment and substance use disorders: A review of the literature and a study in drug dependent adolescents. Attachment and Human Development 7(3): 207-228.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Woodward LJ (2001) Unemployment and psychosocial adjustment in young adults: causation or selection? Social Science and Medicine 53(3): 305-320.

- Sieck CJ, Heirich M (2010) Focusing attention on substance abuse in the workplace: A comparison of three workplace interventions. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 25(1).

- Snow DL, Kline ML (1995) Preventive interventions in the workplace to reduce negative psychiatric consequences of work and family stress. American Psychiatric Association, DC Comics Publishing company, Washington, USA.

- Boatwright KJ, Lopez FG, Sauer EM, VanDerWege A, Huber DM (2010) The influence of adult attachment styles on workers' preferences for relational leadership behaviors. The Psychologist-Manager Journal 13(1): 1-14.

- Humenuik R, Ali R, Babor T F, Farrell M, Formigoni M L, Jittiwutikarn J,et al. (2008) Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction 103(6): 1039-1047.

- Australian Medical Association (2009). Alcohol Use and Harms in Australia.

- Kieselbach T (2003) Long-Term Unemployment among Young People: The Risk of Social Exclusion. American Journal of Community Psychology 32(1): 69-76.