River Pollution, the Leningrad Underground in 1950-80s and Oral History

Malinova Tziafeta O Yu*

PhD in history (kandidat naouk), research fellow at Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences, Europe

Submission: September 02, 2024; Published: September 18, 2024

*Correspondence author: Malinova Tziafeta O Yu, PhD in history (kandidat naouk), research fellow at Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences (Shaninka) / associated at the Department of Modern and Contemporary History with in-depth studying of Eastern Europe, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany (late Prof. Julia Obertreis).

How to cite this article: Malinova Tziafeta O Yu*. River Pollution, the Leningrad Underground in 1950-80s and Oral History. Oceanogr Fish Open Access J. 2024; 17(5): 555971. DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2024.17.555971

Abstract

My article focuses on the construction of water treatment facilities in St. Petersburg/Petrograd/Leningrad (Russian Empire/USSR). Ideas about ecology and the needs of the city changed significantly over time, and each new chapter spread waves of discussion through the community of experts, the city authorities and the underground culture. The problems of bodies of water in the city attracted the closest attention of experts and the city authorities, although the concept of ‘city cleaning’ for a long time meant no more than the restoration of sewage networks destroyed during the Great Patriotic War, and construction of new treatment facilities. The objectives and actions of the city planners followed directly from the old program for the “networking of the city”. But that met a strong underground´s reaction to the discrepancy between the actual state of the city and an aesthetic impressions and “ideal” perceptions about the old St. Petersburg. A new ecological awareness was brought about in Leningrad via this underground-culture, rather than being triggered by the potential benefits of ecological development. Subsequently, ecological issues became an important issue in social confrontations in the city as the USSR headed for collapse.

Keywords: Leningrad; Underground culture; Oral history; Networking the city; Infrastructure history; Sewerage; Water pollution

Introduction

Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, is located in the delta of the Neva River [1], on the banks of numerous small rivers and canals, which in their own way formed the architectural history of the city. However, until recently, history was not inclined to focus on the unpleasant fact that throughout all three hundred years of the city’s life, rivers were used as sewers, absorbing both domestic wastewater and liquid industrial waste1. Despite the fact that already at the beginning of the 20th century new technologies were used to treat domestic wastewater2, problems in this area made themselves felt until the very end of the twentieth century. Throughout this time, the city authorities, the expert community and the general public occasionally converged in heated debates on this topic. My article is about how two characteristic stages in the development of city were bizarrely reflected in public discussions in St. Petersburg / Petrograd / Leningrad [2-7]. On the one hand, there is the stage of construction of urban infrastructure (water supply, sewerage, telephone and gas networks, lighting, urban public transport, suitable streets for it, etc.)3. On the other hand, there is a later stage, characteristic of the 1970s, when the city sought to turn itself into a comfortable living environment, and the closest attention was paid to urban nature4.

1Bater JH (1994) St. Petersburg: Industrialization and Change. London, 1976; Bérard E. Pétersbourg Imperial: Nicolas II, la ville, les arts. Paris, 2012; Späth M. Wasserleitung und Kanalisation in Großstädten: ein Beispiel der Organization Technischen Wandels im Vorrevolutionären Russland // Forschungen zur Osteuropäischen Geschichte. Bd 25. Berlin, 1978. S. 342–360Malinova-Tsiafeta O.Yu. From the city to the dacha: sociocultural factors in the development of dacha space around St. Petersburg (1860-1914). St. Petersburg, 2013; Nardova V.A. City government in Russia in 1860 – early 90s. XIX v. Government policy. Leningrad. 1984; Nardova V.A. Autocracy and city councils in Russia at the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries. St. Petersburg.

2Biman Moscow. Biological methods of neutralizing wastewater by an engineer. M. Biman. Moscow., 1904; Biological treatment of wastewater according to the system of V.I. Kobelev and its device in the sewerage of mansions, apartment buildings, factories, plants, hospitals, schools and various types of city public institutions. Moscow., 1914; Khlopin G.V. Pollution of flowing waters with household and factory waste and measures to eliminate it. A manual for students and doctors. Second corrected and supplemented edition with five figures. Yuryev, 1902.

3Schott D (1999) Die Vernetzung der Stadt. Kommunale Energiepolitik, öffentlicher Nahverkehr und die Production modernen Stadt. Darmstadt - Mannheim - Mainz (1880-1918). Darmstadt.

4Schmandt H (2019) The Quality of urban life. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1969; Baumeister Moscow., Bonomo B., Schott D. (eds.): Cities Contested. Urban Politics, Heritage, and Social Movements in Italy and Western Germany in the 1970s. Frankfurt a. M, 2017; Soens T, Schott D, Toyka M, de Munck Seid B (eds.): Urbanizing Nature. Actors and Agency (Dis)Connecting Cities and Nature Since 1500. New York/ Oxford.

The article analyzes several sources, none of which speak directly about the two stages. Rather, it arose from contemporary historical discussions about urban history in Europe and the United States. Evidence gained from studies of oral history can be compared with data from other sources. That is, oral history is used here rather in frame of a complementary approach. This allows us to decode hidden messages in written sources that were more or less visible and understandable to contemporaries but elude researchers. The very topic of (non-)cleanliness of the city is relative, so the explanatory potential of interviews with experts and ordinary city dwellers is especially important. Sanitary problems / pollution / uncleaned garbage often hides a reference to emotions and ideas that are not related to ecology. According to Mary Douglas, the definition of impurity reflects primarily the violation of order and familiarity which is important for a certain social group5.

Oral history is important here because published sources from the 1950s and 80s spoke very sparingly about the real problems of sanitation and garbage collection in Leningrad. They were much more willing to talk about the achievements of the Soviet communal services and its superiority over the West. That is, in most cases, the historian deals either with the chemical data of sanitary reports that he cannot verify, or with fleeting descriptions, the meaning of which cannot be clarified or questioned in detail, such as published memories about the city. In this case, with the help of oral history and other sources, I describe the peculiarities of the memory of the garbage and pollution of Leningrad. In this case, the oral history is used here mainly as a “key” that can reveal some of the codes of culture and make the most unexpected sources speak. For example, paintings by little-known artists in the 1950-80s [8-10].

The story of the garbage and pollution of the city is an important part of the discussion about the place of ecology in the political and cultural life of Leningrad during the perestroika era. The beginning of this discussion was laid by the idea that the collapse of the USSR occurred as a result of ecocide in the sense that the country’s management did not pay any attention to nature. The Chernobyl disaster and the era of glasnost forced a critical examination of the problems of environmental management; the revealed facts caused mass demonstrations and forever undermined the credibility of the Soviet Kremlin administratio6. Considering the concept of ecocide, historians have repeatedly noted its excessively eschatological nature and pointed out that many factors led to the collapse of the USSR. So, the problems of environmental management cannot be considered as the main factor7. Nevertheless, the term ecocide has been widely used in the historical literature8. Reports of sewage were often accepted as independent and objective eyewitness accounts. My article describes not only how the townspeople born in the 1940s and 50s remember the sanitary condition of Leningrad, but also examines their emotional and political ideas behind these memories [11].

The interviews were collected in 2015-2016 (about 50) ranging in length from 11 hours to 20 minutes. The questionnaire provided a somewhat abstract question “what did the city of your youth look like?”. Some respondents talked about garbage and sanitary problems without any prompting. But for many other respondents, the topic of garbage was completely irrelevant. Apparently, such stories were not memorable and did not play any noticeable role in their lives. I had to abandon the clarifying question, “What was the city of your youth, rather clean or rather dirty,” because it baffled many respondents. Some of them asked what I meant, and then said that they had barely thought about it. In the context of expert interviews with hydrologists, a question was also asked about the sanitary condition of water bodies, about discussions inside the expert community and the reasons for a (non)interference in these discussions [12-15].

Intertwining of two city development stages in Leningrad 1950-80s

The history of the sewage system in pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg and wastewater treatment in general is a history of a long choice of projects and the general indecision of the city authorities. The phase of construction of urban networks (Vernetzung der Stadt) was delayed here for a particularly long time in comparison with large European cities (London, Paris, Frankfurt am Main), and with many cities of Russia. Before the First World War, only about four dozen cities in Russia were equipped with sewerage – the most complex and costly project of its time9. To describe this St. Petersburg phenomenon, I proposed a metaphor of paralyzing perfectionism. For example, a commission within the City Duma, faced with the choice of an urgent and undoubtedly important technological project, had been at this stage for almost 50 years. An important reason for this was concerns about possible risks. The pattern was the endless search for the perfect solution. The public criticized the city order in the press, and the city authorities justified themselves, referring to all sorts of obstacles: it is impossible to get plans for secret underground communications, the high cost of the project, etc. Ultimately, the public of the city Duma themselves recognized that sewerage was more important for the urban poor, while wealthy people used numerous avoidance strategies (they left the city in the epidemiologically dangerous summer months) and devices (used disinfectants, water filters, numerous preventive health measures). The intervention of P.A. Stolypin (1909) produced a short-lived effect of acceleration: the project was chosen, and construction began on the experimental site of Vasilyevsky Island. Yet following his death (1911) and the beginning of the First World War (1914), the case again entered a slow mode10.

5Douglas Moscow. (1985) Reinheit und Gefährdung: eine Studie zu Vorstellungen von Verunreinigung und Tabu. Berlin.

6Feshbach M, Friendly Jr. A (1992) Ecocide in the USSR: Health and Nature under Siege. Basic Books. New York.

7Elie M (2013) Late Soviet Responses to Disasters, 1989–1991: A New Approach to Crisis Management or the Acme of Soviet Technocratic Thinking? // Soviet and Post-Soviet Review. 40(2):214–238; Gestwa K. Die Stalinschen Großbauten des Kommunismus: Sowjetische Technik- und Um-weltgeschichte, 1948–1967. Munich, 2010; Obertreis J. Von der Naturbeherrschung zum Ökozid? Aktuelle Fragen einer Umwelt-geschichte Ost- und Ostmitteleuropas // Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contempo-rary History 2012 URL: (http://www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/1-2012?q=node/4621); Oldfield JD. Russian Nature: Exploring the Environmental Consequences of SocietalChange. Burlington, VT 2005.

8Tziafetas G (2015) Review on: Laurent Coumel and Marc Elie (eds). A Belated and Tragic Ecological Revolution: Nature, Disasters, and Green Activist in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet States, 1960s–2010s. // Special issue of Soviet and Post-Soviet Review, 40 (2013) 2, in: Laboratorium 7(2): 221-225.

After the revolution of 1917, there was hope that this longstanding problem would finally be solved. During this period, the state began to improve and build urban networks (primarily water supply and sewerage) in all cities of the USSR. The storm sewerage system in Petrograd began in 1918, despite all the hardships of the Civil War11. The development of a project for a new type of collector sewerage began at the same time. The construction of underground networks continued immediately before the outbreak of the war but was stopped by the blockade. As you know, the city’s water supply and sewerage system ceased to function in the first winter of the blockade, the networks were seriously damaged because of freezing and was partially destroyed by air raids. By the end of the war, the system was seriously damaged. The system had to be restored and completed12. Not only Leningrad, but also the entire European part of Russia was destroyed or badly damaged twice in 30 years. Thus, the phase of construction of urban networks did not lose its relevance during the first half of the 20th Century. In the post-war decades, a sewerage system and a metro were built in Leningrad, and other underground networks were laid. The state actively promoted an extremely ambitious program for the construction of separate apartments for each family13.

In Leningrad, it took the state too long to implement a wastewater treatment program. At the same time, the nascent Soviet consumer society in the 1950-80s. was not completely cut off from Western ideas, values, and goods14 and also aspired to life in the city as the most comfortable living environment. In part, Leningrad could satisfy such aspirations: museums, concert halls, parks and restaurants were located here and, most importantly, were quite accessible to almost all citizens15. For example, Soviet tourists in Paris immediately noted the fragrance and cleanliness of the French capital compared to Moscow, where, according to fashion historian A. Vasiliev, unpleasant odors greeted the citizen at the entrance to public transport16.

In the world’s cities, residents placed high priority on urban nature replicating the natural environment; but in my interviews, respondents never complained about the lack of parks or squares in the city. Here, the question of criticism of the urban “environment” was rather in the sloppy appearance and abandonment of monuments of urban architecture. For example, a beautiful pre-revolutionary Art Nouveau building could be hidden behind a rickety vegetable stall with a mountain of dirty boxes, etc. The disorder is evident in the photographs of that time and can be clearly heard in the interviews I collected in 2015-2016. That is, urban nature and the architecture of the old city were perceived as an indivisible whole. At the level of the expert community, the problems of environmental pollution were discussed and gradually solved17, but the state of the city was assessed rather negatively [16-18].

Canal mud water as a symbol of spiritual stagnation

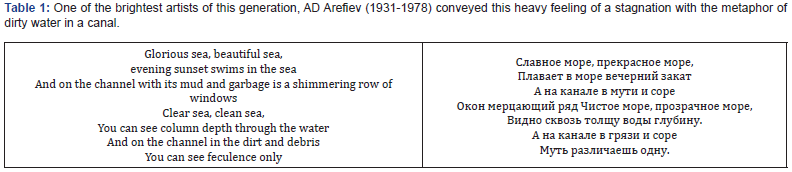

For the rebellious youth of the late 1940s and early 50s. The dirtiness of the city’s rivers and canals was one of the symbols of the restrictions imposed by official culture and ideology. Georgiy (Georges) Fridman (1931-2018), a Leningrad jazzman who became a Catholic priest in the USSR in the 1970s, wrote: “We were suffocating from the ubiquitous Sovietism” (my zadykhalis` ot vezdesushchej sovetchiny). By the 1950s, their protest would have been extreme for the late Stalin and the early post-Stalin era. In the late 1940s and early 50s a young Jewish man, swimmer and then aircraft engineer D. Aksyonov hung a photo of the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) with swastikas on their sleeves in his room above his bed, and his parents refused to visit him. Friends found that he looked German, and bragging about it, he liked to repeat: “The Führer told me: Paul, you are going east”18. One of the brightest artists of this generation. A.D. Arefiev (1931-1978) conveyed this heavy feeling of a stagnation with the metaphor of dirty water in a canal19 (Table 1).

9Bönker K (2010) Jenseits der Metropolen: Öff entlichkeit und Lokalpolitik im Gouvernement Saratov (1890–1914). Köln; Weimar; Wien. pp. 244- 245.

10Malinova-Tziafeta O.Yu (2013) From the city to the dacha: socio-cultural factors in the development of dacha space around St. Petersburg (1860- 1914). SPb. pp. 142-157.

11News of the Petrograd City Public Administration. 1918. No. 58. August 14, Wednesday.

12Dmitriev VD, Burenina IA, Krasnov IA (2005) Water supply and sanitation of Leningrad during the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945). St. Petersburg.

13Harris SE (2013) Communism on Tomorrow Street: Mass Housing and Everyday Life after Stalin. Washington, Baltimor 2013.

14Ivanova A (2017) Beryozka stores: consumption paradoxes in the late USSR. Moscow.

15Kotov V (2019) Valery Popov: “Soviet writers in the 1960s could drink every day at the European Hotel” // SPb Sobaka.ru, Access mode: http:// www.sobaka.ru/bars/trends/47946 (date of access 7.11.2019).

16Vasiliev A (2019) A woman should be a servant in all respects // Let’s talk? Interview with Irina Shikhman. Access mode: https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=4xrdejtYL28 (date accessed: 07.11.2019).

17Tsvetkova LI, Kopina GI, Kupriyanova LM, Varlygo AA (1974) Pollution of the Neva River with organic substances // Collection of works of the Leningrad Civil Engineering Institute. 1: 92.

It’s more about an unattainable dream than a political critique of Soviet reality. The canal that became a symbol of the sense of deadlock from which everyone was looking for their spiritual outlet. A similar feeling was peculiar not only to a narrow circle of the Leningrad underground of the 1950-60s. The film director Larisa Shepitko received thousands of letters from viewers after her film “The Ascent” (1976). Regulatory authorities believed that a “religious parable with a mystical tinge” was shot instead of a partisan story. But it also attracted viewers20. This way of life was often risky for Georges Friedman’s friends. Men and women, artists and musicians, they often searched for themselves in promiscuous sexual relations, drug addiction and alcoholism. So, some of them ended their lives young, some were in prison. For Georges himself, the only positive decision was to turn to Christianity. The metaphor of the dirty channel as life stagnation became in his memoirs an important explanation for such a way, unacceptable to his Jewish family and friends21.

George Friedman and his friends became part of the informal and semi-legal cultural movement “the second culture” (an alternative to official culture, whose figures could print their works and address the public at concerts and from television screens). This circle perceived the city in their own way. The ideal for them was the Fin de Siècle period, rather hushed up in official Soviet culture. One of the important ideas in the cultural space of Leningrad was that architectural forms had a human spirit, and therefore negligence in the appearance of the city is tantamount to immorality. This view represented a logical opposition to the understanding of progress by the city government, whose rather utilitarian approach to urban planning in practice allowed for some sloppiness. In photos of 1970s they can see a rotten fence directly opposite the magnificent embankment [19-21].

On the outskirts of the city, unsightly Khrushchev houses surrounded the country mansions of the pre-revolutionary nobility with their artificial reservoirs and picturesque rivers. Ponds and rivers interfered with construction, increasing costs. Therefore, the rivers were either enclosed in concrete pipes or drained. Sometimes dried riverbeds were left in the form of wastelands, surrounded by landscaped microdistricts. They often did not try to find any suitable use for them: to lay out a park, to arrange playgrounds, to put gazebos [22].

One of the strategies of the townspeople in relation to urban disorder was complaint and active interaction with local authorities, the other was the independent cultivation of the space next to the house (planting trees, flowers, self-cleaning of the territory). The third strategy was a semblance of “extrafindability” described by A. Yurchak and meaning a kind of passive perception of ideological postulates and public duties22. Unrecognized Leningrad artists went even further: not only did they ignore the Soviet ideology, but they also had the ability to overlook the very signs of their time. For example, in the works of Arefiev’s group – one of the oldest independent groups of artists – cityscapes often appear in a haze as artists seem to mask new elements that have emerged around harmonious architectural objects. In photographs and canvases of the 1960s and 1970s, the main role is played by the city itself - if people appear in these works, they remain subordinate to the spatial logic of the city. In the memories of Leningrad residents from the artistic and musical environment, the chilling idea that Leningrad was most beautiful during the first siege winter of 1941-42 - without transport, no people on the streets. Later, this idea would be reflected as the memories of the negative hero in Dina Rubina’s novel “The White Dove of Cordoba”: “You know, my father claimed that he had never seen Petersburg as beautiful as in the siege: a dead city, indoctrinated, as in a good engraving, buildings. Death becomes this sorrowful city, built on the swamp and on the human bones”23. The novel was about a man who was fascinated by the great masters of painting and attached little importance to the people around him and human life in general [23].

18Friedman G (2006) In Search of God (The Path to God) / Manuscript of memoirs, prepared for publication by Fr. Georgy Friedman and preserved in several copies. From the home archive of Olga Malinova-Tziafeta. St. Petersburg, 2005-2006. P. 50-51.

19Friedman, In Search of God, p. 56.

20The Interview of Felicitas von Nostitz with Larisa Shepitko, Western Berlin 1978. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZdVGxQaCm8 19.04 – 20.48 min.

21Friedman, In Search of God, p. 45.

22Yurchak A. It was forever, until it ended. The last Soviet generation. Moscow, 2014. S. 255-310.

23Rubina D (2009) “White Dove of Cordoba” M. p. 327.

In the works of Leningrad protest artists there was a sense of life as it is, but with a negative, sometimes even deviant charge. The extreme form of such interest is the works of A. Arefiev, where he painted scenes of sexual violence against women “from nature”. The artist himself said that he climbed a tree in the city cemetery and used this shelter to create sketches of his unwitting sitters24. For us, it doesn’t matter so much whether it was outrageous bluster or not. What matters is that a group of artists rejected the canons of socialist realism, whose purpose was to represent a role model and thereby instruct people on the “true path”. This withdrawal threatened criminal charges of slandering the socialist system. At the same time, artists often tended to perceive positive images as false, as a tribute to censorship and propaganda. Another important aspect of this circle was its emphasis on Westernism: a special interest in Western literature, painting and music25. America became for artists and musicians a mythical continent, where beauty and freedom of creativity reigned [24].

Dirty canal water in 1970s as a symbol of antisovietism?

For representatives of the “second culture”, born in the late 1940-1950s, evidence of life’s deadlock and unrecognizedness was rather a metaphor for the underground: “In the basement you can find only rats.” 26 But the garbage and untidiness of the city rivers was rather an accusation of indifference and addressed to officials from the Committee for the Protection of Monuments. Young local historians, writers, artists, unrecognized by the official Soviet institutions of science and culture, defended their place in the cultural space of the city - and could not find it. However, in the era of perestroika, many of them earned interest and attention to their work, and after 1991 had the opportunity to develop their political ideas. The Soviet government in their eyes was indifferent to them and simply doomed to change. They insisted that St. Petersburg was their city, and they should be allowed to make decisions about the fate of historical buildings. In the 2010s. The “Spaseniye” (Salvation) group acknowledged that their criticism of the Committee for the Protection of Monuments was unnecessarily sharp and strict. However, memories of the pollution of the city’s rivers and the untidiness of the city were not revised.

Leningrad residents of St. Petersburg, generally loyal to the Soviet government and the socialist system, remembered the pollution of the city in a slightly different way. They noted the most unsettled, even shocking examples – but in general, the city did not look dirty in their eyes. So, although the city sewer was restored in the 1940s, waste flowed into the city’s rivers, including the Obvodny Canal. Before the revolution, it passed through the industrial part of the city and the workers’ quarters, but by the 1960s the area was already densely populated and even gravitated to the center of Leningrad. Along the embankments there were multi-storey stone houses of pre-revolutionary construction. YM (born in 1951, A civil servant), recalled: “My mother and I went to the Frunzensky department store to buy me uniforms for school. So, it smelled so much -- worse than the toilet. It was hard to breathe there! I kept thinking, how do people live there?” Obviously, the teenage boy didn’t find this situation routine -- once he remembered it in his sixty-plus years. Another informant, EA (born in 1945, a historian), recalled how in the 1950s he and his friends walked along the banks of the Obvodny Canal and observed that there, in addition to garbage and “live shit” (meaning an unfiltered sewage drain), the most intimate household items floated there, including used condoms. The boys looked at and commented on floatingobjects, and even 60 years later, EA talked about it with laughter and excitement. The informant did not tell such stories about the Fontanka or the Kryukov Canal, which flowed not far from his home. That is, the Obvodny Canal still seemed to represent some exception to the rule. It is ludicrous that both informants tend to emphasize rather the positive aspects of Soviet reality and even in their youth did not share anti-Soviet feelings.

Analysis of interviews and direct questions to informants do not allow us to classify this criticism as some specifically environmental sentiment. On the contrary, in many cases, everyday observations had to do with either spiritual and creative searching or hidden criticism of authority. Opposition sentiments were not encouraged, but often directly suppressed by ideological structures in state power, criticism habitually turned to the relatively neutral topic of urban improvement and water protection. It is curious that this was realized and explained by the respondents themselves: “Here I say, oh there, I don’t know, Brezhnev is bad! - Oh, and [if] I say [instead] like, “Damn! The flowers are wilting!” (Blyad`! Сvety vyanut!) – so, I said the same thing, in fact, you know?! Essentially, I said the same thing! That I am not satisfied with the government! That it is bad. But I [at the same time] do not punish” EA (born in 1945, historian).

Pollution of urban rivers in the public debate of the perestroika era

Dry data from sanitary studies of urban rivers showed that they were polluted, and that the treatment of sewage was needed. The Baltic Sea brought its own answer to the problem in the mid-1980s. It was the increased eutrophication and the spread of cyanobacteria or blue-green algae, which multiply rapidly in polluted water bodies. The bacterium blocks oxygen and is therefore particularly dangerous to aquatic life. The main impetus for solving the problem was the international conference of HELCOM in Helsinki in 197427. A program for the treatment and monitoring of wastewater in Leningrad was developed, and the construction of treatment infrastructure began28. Here a natural question arises, why did it take so long to clean the sewage? - Hydrologist NV (1948) gave his own answer: he believed that Moscow could not allocate funding for such a large-scale project.

24Gurevich L (2002) Arefievsky circle. St. Petersburg.

25Ibid, Friedman G. In Search of God (The Path to God), pp. 39-45, 47-51; Yurchak A. It Was Forever, Until It Ended, pp. 311-403.

26Grigorenko PG (1981) In the underground you can only meet rats. NY.

The quality of life in Leningrad in the 1970s was already much better than in many other cities USSR, and it was really to legitimize it. Hydrologists were told: “You have the Gulf of Finland, so there is no reason to build a sewage treatment plant!”- However, when the decision was made, the press proudly announced new construction plans29. The first stage of the Central Aeration Station was put into operation in 1978, the second in 1985. The northern station was built in 1986, the series was completed in 1994. This was not enough for the city, huge areas in the South- West continued to drain sewage into the bay, and in 1987 the construction of the South-West treatment facilities began. It was completed only in 2005 after a long break. It seems that in the late 1970s, Leningrad residents had every reason to be optimistic, but the hidden discontent with the city authorities was already obvious.

In the era of perestroika, the “second culture” finally received recognition and attention. Not only theatrical, musical and artistic groups crystallized here, but also groups of protest social activism. The most progressive part (the group “Salvation”) was concerned with the salvation of the architectural heritage of Leningrad30. The “Delta” Group focused its efforts on stopping the construction of the Leningrad Flood Protection Complex, an almost completed chain of protective dams in the Gulf of Finland. Oral history interviews show that the human scientists and artists were somewhat sympathetic to this activity31.

The “second culture” was characterized by an aesthetic appeal to pre-revolutionary culture. The focus was also on a prerevolutionary ideal that hardly existed in reality. The legendary writer Sergei Dovlatov joked about this in his novel “The Branch”: “Many even believe that our future, like the crayfish, is behind us.” And the action of absolute purity of the city is clearly traced in the memoirs of D.A. Zasosov and V.I. Pyzin, written in Soviet times, but published for the first time in the magazine “Neva” in 1987- 8932. Meanwhile, historians know that in 1860-1917 the demand to clean the city’s rivers and soil from rotting organic residues became socially significant and even political. It was believed that they provoked the deadly epidemics of typhus, cholera and scarlet fever - but memoirists born before the revolution forgot about it.

The statement about the purity of the pre-revolutionary city, referring rather to the white emigration and its nostalgia, reliably rooted about the society and among the opposition artists in the USSR. In the paintings, a lady in a luxurious light ball gown sits right on the stone steps of the granite embankment, and the city for her is as clean as the living room (Vasilij Kuchumov, 1920). The work of the 1980s. shows another young lady in a ball gown in the morning on the balcony, where the breakfast table is set and there is not a hint of the reality of the city: the table is not hidden by a canopy from birds, there are no shadows from dust and so on (Andrey Sibirskiy, the Elegy). The St. Petersburg idea of the pre-revolutionary perfection of the city was so strong that it seemed to force representatives of the counterculture to forget the novels of F.M. Dostoevsky, in which the city is dirty, and the heroes are poor and dependent. Dostoevsky`s works were not studied in Soviet schools of the 1940-50s, and therefore such reading was considered a manifestation of free thinking, so that the well-educated persons born in the 1930s highly appreciated the writer33.

One of the requirements of the “second culture”, i.e. the counterculture, was “purification”, which was understood very broadly: the purification of rivers and canals from waste and industrial effluents, the purification of the history of the city from undesirable ideological patina and the cleansing of the whole country from communism34. That is, communist rule and its symbols were placed on a par with the pollution of space, and communist ideals were thus recognized and ousted from the new system of values. At the same time, in the summers of 1986 and 1987, which turned out to be especially hot, environmental problems in the Gulf of Finland clearly manifested themselves: its sandy beaches were covered with unpleasant thorny algae and green slime, clearly indicating a strong eutrophication. It was difficult for the city authorities to find convincing counterarguments, the authorities tried to evade public discussion of this issue by giving the floor to the civil engineers of the Leningrad Dam. Analysis of the transcripts of the discussions in the editorial office of the newspaper “Smena” showed that the experts were most likely not prepared for this task. They were accustomed to scientific discussions, the style of public debate was new, unusual and unpleasant to them, so they could not seriously influence the opinion of the humanitarian community35. Meanwhile, the ecological situation in Leningrad clearly did not meet the heightened requirements for the urban environment.

27McCormick J (2004) Reclaiming Paradise: The Global Environmental Movement. Bloomington, 1991; Rytövuori H. Structures of Détente and Ecological Interdependence: cooperation in the Baltic Sea Area for the protection of marine environment and living resources // Cooperation and Confl ict. 1980. XV, р. 85-102; Selin H., VanDeveer S.D. Baltic Sea Hazardous Substances management: Results and challenges // Ambio 33(3): 153-160.

28Beck U (2003) Risikogesellschaft: Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne. Frankfurt-am-Main, S. 59-63.

29Construction of the Leningrad Flood Protection Complex has begun // Pravda. 1979. August 19.

30Gladarev B (2013) “This is our city!”: analysis of the St. Petersburg movement for the preservation of historical and cultural heritage // Urban movements of Russia in 2009–2012: on the way to the political / edited by K. Kleman. Moscow. Pp. 23-142.

31Tziafetas G (2014) The Ecologists versus the Builders: The Confl ict over the Leningrad Dam in the Nineteen-Seventies and Eighties // Saint Petersburg Historical Journal. №1, S. 182–189.

32Zasosov DA, Pyzin VI (1999) From the life of St. Petersburg 1890-1910: Notes of eyewitnesses. St. Petersburg.

33Friedman, In Search of God, p. 79.

Public opinion in Leningrad insisted on the complete closure of harmful enterprises and even on the transfer of the Northern Aeration station even further from the city boundaries36, i.e. the restructuring of the most important assets for the city, which had only recently been put into operation (1986), and then not completely (subsequent parts were commissioned until 1994)37. The ideas of the “second culture” coincided here with the fears typical of Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society. Suffice it to recall one of the most feared rumors. It was said that St. Isaac’s Cathedral, one of the symbols of St. Petersburg, could soon collapse, since its foundation was historically located on wooden piles impregnated with a special “pre-revolutionary” composition, and poisonous industrial wastewater from the Soviet period allegedly corroded this and now threatened the building with complete destruction. This idea was also broadcast by the recognized prose writer A. Bitov38. Thus, following Mary Douglas, untreated sewage symbolized socialist rule and posed a danger to the values of the creative intelligentsia, in this case to the architectural appearance of St. Petersburg.

City structural experts could not win the attention of citizens. Representatives of hydrological science rarely tried to give refutations, although they discussed press news among themselves rather as anecdotes. A direct question about the reasons for noninterference was followed by the same type of answer in different interpretations. For example, NN (born in 1945, Ph.D., researcher at the State Hydrology Institute):” how do you argue with this nonsense? And, most importantly, what for? These people had their own goals, they did not want to listen to anyone else. You [addresses the interviewer – O.M-Tz.] understand it as an adult: well, what composition can save wood from rotting? In a moist soil? For so many years?!». For example, defending their values was obviously so important to the adherents of such stories that they did not consider it necessary to think about the reliability and logic of the information. Experts often did not try to convey the truth, since they were accustomed to conducting scientific discussions and looked down on informal environmental and cultural activism.

As a result, the unfinished stage of the construction of urban networks faced the requirements of a new stage in the construction of an ecological city. However, in public discussions, the adherents of these two stages began to sharply oppose each other, not noticing or not wanting to notice the illogic of such a confrontation39. Experts (engineers, hydrologists, representatives of the Leningrad Executive Committee) in the late 1980s - mid- 1990s suggested that many public groups join forces. Informal public associations could help the state service for the protection of water bodies to locate the places of illegal untreated industrial effluents, mowing algae in urban water bodies, etc. However, environmental activists strongly rejected this proposal. They said they did not intend to duplicate the work of state institutions40. Obviously, such contradictions were fueled by the heated political discussions characteristic of this era of social order transformation.

Conclusion

So, the two stages of the city’s development: the construction of urban networks (Vernetzung der Stadt) and the ecologization of the urban environment could neither incorporate nor smoothly replace each other, but instead crystallized into two conflicting groups during the period of perestroika. On the one hand, there were people who were directly involved with the construction and operation of networks (city authorities, experts). On the other hand, representatives of the humanitarian and creative intelligentsia with their own values and perceptions of urban issues, as well as the general public. Experts in their reports pointed out that sewerage and treatment facilities were necessary for Leningrad and that the water was really heavily polluted. At the same time, the ideas of the “second culture” about dirt in the canals had many additional meanings that had nothing to do with the environment. Already in the 1950s, the dirty canal had become a literary metaphor for the spiritual impasse, as well as the lack of recognition for creative works, and sometimes just the talents and ambitions of representatives of the “second culture” in the city cultural space. Garbage and dirty water in the rivers became evidence of the accusation against the city authorities of indifference to architectural appearance, and hence to the efforts and values of the “second culture”. Thus, the pollution of the city, loaded with additional meanings, easily became a symbol of protest in the era of perestroika. It is obvious that the attitude to urban space in St. Petersburg also depended on the history of the construction of urban networks (primarily sewerage), the complex geographical position of the city, as well as the political, economic, and cultural characteristics of the northern metropolis in the USSR.

34Tziafetas G (2014) The Ecologists versus the Builders: The Confl ict over the Leningrad Dam in the Nineteen-Seventies and Eighties // St. Petersburg Historical Journal. №1, S. 182–189.

35Ibid.

36Interview with NM (born in 1952, historian), who in the late 1980s was part of a group of environmental activists in the village of Olgino, 25.01.2013.

37The Northern Aeration Station turns 32 // State Unitary Enterprise Vodokanal of St. Petersburg, official website. Access mode. 38Bitov A (2004) About window washing // Volkov S. History of the culture of St. Petersburg from its foundation to the present day. Moscow. P. 643-644.

39The irreconcilability of discussions and the severity of mutual reproaches are evidenced by the transcript of the meeting between representatives of the Delta Group and representatives of the expert community responsible for the environmental aspects of the construction of the Leningrad Dam: Sosnov A. Without personal scores // Smena 1987, October 23; Sosnov A. Is it about the dam? // Smena 1987, October 20; Sosnov A. Why muddy the waters? // Smena 1987, October 21.

40Interview with former employees of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Council (late 1980s-early 1990s), November 15, 2016.

References

- Biman M (1904) Biological methods of wastewater treatment by engineer M. Biman. [Biologicheskie sposoby obezvrezhivaniya stochnyh vod inzhenera Bimana].

- (1914) Biological wastewater treatment according to the Kobelev system and its installation in the sewerage of mansions, apartment buildings, factories, factories, hospitals, schools and various kinds of city public institutions. [Biologicheskaya ochistka stochnyh vod po sisteme tekh. V.I. Kobeleva i ee ustrojstvo pri kanalizacii osobnyakov, dohodnyh domov, fabrik, zavodov, bol'nic, shkol i raznogo roda Gorodskih Obshchestvennyh uchrezhdenij]. Moscow.

- Bitov A (2004) About window cleaning [O myt'e okon] // Volkov S. Istorija kul'tury Sankt-Peterburga s osnovanija do nashih dnej. - Moscow. pp. 643-644.

- (1979) Construction of the Leningrad Flood Protection Complex has begun [Nachalos' stroitel'stvo Kompleksa zashchity Leningrada ot navodnenij] // Pravda. 19 avgusta.

- Cvetkova LI, Kopina GI, Kuprijanova LM, Varlygo AA (1974) Pollution of the Neva River with organic substances [Zagryaznennost' reki Nevy organicheskimi veshchestvami] // Sbornik trudov Leningradskogo inzhenerno-stroitel'nogo instituta. Vyp. 1: Himija. 92. C. pp. 39.

- Dmitriev VD, Burenina IA, Krasnov IA (2005) Water supply and sewerage of Leningrad during the Great Patriotic War, 1941-1945. [Vodosnabzhenie i kanalizaciya Leningrada v period Velikoj Otechestvennoj vojny (1941-1945)]- St. Petersburg.

- Fridman G (2006) In Search of God (The Path to God) [V poiskah Boga (Put' k Bogu)] / Manuscript of memoirs prepared for publication by Fr. Georgy Friedman and preserved in several copies. From the home archive of Olga Malinova-Tziafeta. - St. Petersburg 2005-2006.

- Gladarev B (2013) This is our city! analysis of the St. Petersburg movement for the preservation of historical and cultural heritage [«Eto nash gorod! »: analiz peterburgskogo dvizheniya za sohranenie istoriko-kul'turnogo naslediya] // Gorodskie dvizhenija Rossii v 2009–2012 godah: na puti k politicheskomu/ pod red. K. Kleman. - Moscow.

- Grigorenko PG (1981) In the basement you can find only rats… [V podpol'e mozhno vstretit' tol'ko krys...]- NY.

- Gurevich L (2002) (Ed.) Arefiev circle. [Aref'evskij krug]. - St. Petersburg.

- Hlopin GV (1902) Pollution of running waters with household and factory waste and measures for its removal. A manual for students and doctors. Second revised and additional editions with five drawings. [Zagryaznenie protochnyh vod hozyajstvenymi i fabrichnymi otbrosami i mery k ego ustraneniyu. Posobie dlya studentov i vrachej. Vtoroe ispravlennoe i dopolnennoe izdanie s pyat'yu risunkami]. - Jur'ev.

- Ivanova A (2017) Beryozka stores: paradoxes of consumption in the late USSR. [Magaziny «Berezka»: paradoksy potrebleniya v pozdnem SSSR]. - Moscow.

- Jurchak A (2014) Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. [Eto bylo navsegda, poka ne konchilos'. Poslednee sovetskoe pokolenie]. Moscow.

- Kotov V (2019) Valery Popov: “Soviet writers of the 1960s could drink every day at the Hotel „Europeyskaya [Valerij Popov: „Sovetskie pisateli v 1960-e mogli kazhdyj den' vypivat' v gostinice Evropejskaya"] // SPb Sobaka.ru, Rezhim dostupa: http://www.sobaka.ru/bars/trends/47946 (data obrashhenija 7.11.2019).

- Malinova Tziafeta O Ju (2013) From city to dacha: sociocultural factors in the development of dacha belt around St. Petersburg, 1860-1914. [Iz goroda na dachu: sociokul'turnye faktory osvoeniya dachnogo prostranstva vokrug Peterburga (1860-1914)]. -St. Petersburg.

- Nardova VA (1994) Autocracy and city councils in Russia at the end of the 20th – beginning of the 20th centuries. [Samoderzhavie i gorodskie dumy v Rossii v konce XIX – nachale XX vv.]- St. Petersburg.

- Nardova VA (1984) City government in Russia in 1860 – early 90s. XX century Government policy. [Nardova V.A. Gorodskoe samoupravlenie v Rossii v 1860 – nachale 90-h gg. XIX v. Pravitel'stvennaya politika]. Leningrad.

- News of the Petrograd City Public Administration [Izvestiya Petrogradskogo gorodskogo obshchestvennogo upravleniya]. (1918) № 14 avgusta, sreda.

- Rubina D (2009) The White Dove of Cordoba. [Belaya golubka Kordovy]. Moscow.

- Sosnov A (1987) Is it the dam? [V dambe li delo?] // Smena 1987, October 20.

- Sosnov A (1987) What for too muddy the waters? [Zachem mutit' vodu?] // Smena.

- Sosnov A (1987) Without personal accounts [Bez lichnyh schetov] // Smena, October 23.

- Vasil'ev A (2019) A woman should be a servant in every way [Zhenshchina dolzhna byt' obslugoj vo vsekh otnosheniyah] // A pogovorit'? Interv'ju Irine Shihman. Rezhim dostupa: (data obrashhenija: 07.11.2019).

- Zasosov DA, Pyzin VI (1999) From St. Petersburg life, 1890-1910. Eyewitness notes. [Iz zhizni Peterburga 1890-1910 gg.: Zapiski ochevidcev.]. -St. Petersburg.