Environmental Perception of Recreational Fishers in Urban Beaches

Natália Duarte da Silva and Jacqueline S Silva-Cavalcanti*

Laboratório de Oceanografia e Poluição de Ambientes Aquáticos, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Brasil

Submission:May 24, 2021; Published:August 02, 2021

*Correspondence author: Jacqueline S Silva-Cavalcanti, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Unidade Acadêmica de Serra Talhada, Laboratório de Oceanografia e Poluição de Ambientes Aquáticos, Av. Gregório Ferraz Nogueira, s/n, São Tomé de Souza Ramos, Serra Talhada, Pernambuco, Brasil

How to cite this article: Natália D d S, Jacqueline S S-C. Environmental Perception of Recreational Fishers in Urban Beaches. Oceanogr Fish Open Access J. 2021; 14(2): 555881. DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2021.14.555881

Abstract

Recreational fishers depend on the good quality of those environments. The assessment of the environmental perception of social actors who show a sense of belonging to the landscape can better describe the impacts on the environment. This study aimed to assess the recreational fishers’ perception of the environmental quality in four urban beaches. 170 recreational fishers agreed to participate in the research. They were required to respond to questions about their fishing strategies and their perception of the environmental quality of the beaches and the possible impacts on the fishing activity. Based on the responses presented, a description of both local fishing activities made, as well as an analysis of the perception of the beaches’ environmental quality for fishers. On average, the recreational fisher ones have been working for 16.2 years. Pollution considered be the cause of diversity loss and local fauna’s biomass loss by 70% of recreational fishers. The second main cause of those losses was the alterations on the natural landscape, reported by 50% of the recreational fisher ones. A PCA showed that to the recreational fishers the biodiversity and biomass loss related to the pollution over time (55.15%). Although the quality of the beaches is not satisfying to any of the fishers, they continue to attend and fish in those beaches.

Keywords: Environmental valuation; Urban fishing; Recreational fishing

Introduction

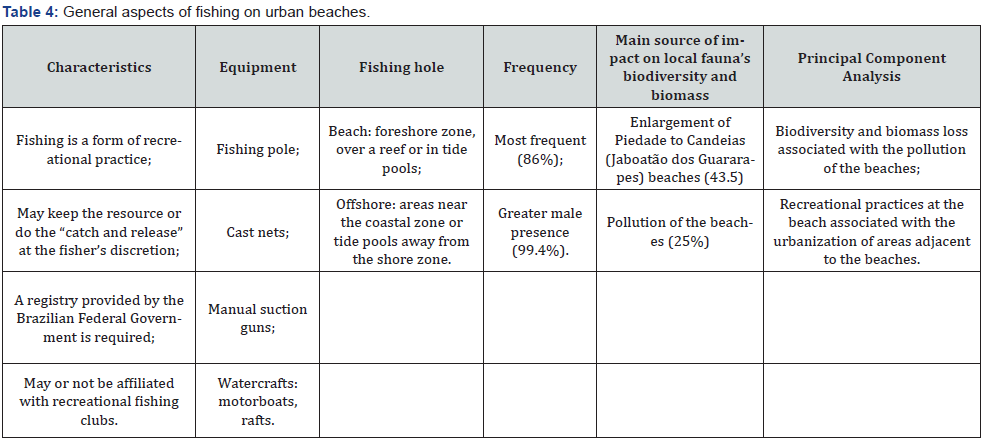

In urban beaches can find fishing activities its main purpose is recreation, where the fisher may release the animal caught while it is still alive (“catch-release”), or even kill it and keep it for various reasons (e.g., serving as bait for fishing or own consumption) [1]. In these fisheries, the commercial relationships concerning the volume caught are nonexistent [2,3]. The recreational fishing has been developing much in the last decades. Studies shows that in some regions (e.g., EU, USA, India) recreational fishing has become as much or more important than commercial fishing [4,5].

The recreational fishing still is hard to monitor due mostly to the mobility of its practitioners and the different strategies adopted, but some researchers are interested on recreational fisher monitoring owing to the impacts of recreational catch on the marine biodiversity [6-11]. However, despite the negative impacts on biodiversity, recreational fishing plays an important social-ecological role in favor of biodiversity conservation for it is a way of raising ecological awareness and respect for nature in people who do not economically depend on these resources and the coastal environment [12].

The knowledge and the environmental perception of fishers are very important to analysis about the environmental quality of the coastal ecosystems [13,14]. Their dependence on the environment makes them more likely to realize changes in the marine ecosystem, so, they environmental perception can be very useful to make management strategies [15,16]. This is fundamental for the success of the management because relates on the users’ involvement with the ecosystem managed [17,18].

In this sense, the environmental management strategies for urban coastal zones can defined by assessing the perception of the actors involved with the natural environment in use. For that, it is necessary to understand the social processes, attitudes, and perceptions of the environmental quality by the fishers [19-21]. Therefore, studies aimed at the assessment of the environmental quality, based on the fishers’ perception, related to the necessity or success of environmental and fishing management measures, are getting more and more attention [19,22,23].

Based on the factors presented above we evaluated the hypothesis that the biodiversity loss on urban beach reefs is related to human impacts in the ecosystem and rising pollution. To conduct the research, we based on the environmental perception of recreational fishers about the environmental quality of urban beaches where this group often frequents, highlighting the effects temporary changes and their influence on the loss of fish fauna biodiversity on this beach.

Materials and Methods

Study area

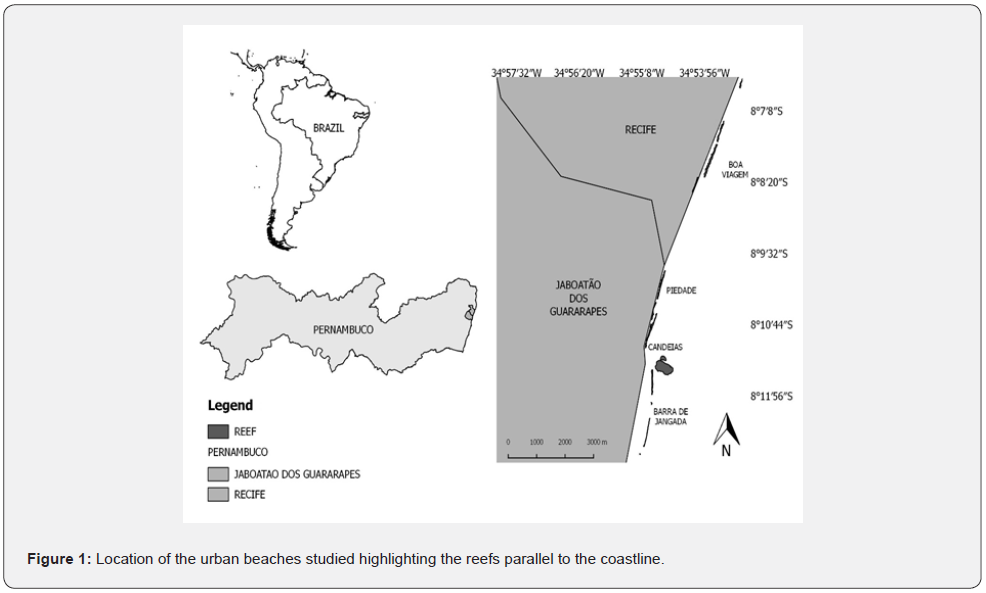

This research performed on someone urban beaches of Pernambuco: Boa Viagem, Piedade, Candeias and Barra de Jangada. Those beaches are 16 km a long in the largest cities in the state of Pernambuco: Recife and Jaboatão dos Guararapes (Figure 1). Together are characterized by a high concentration of population and intense use over the whole year (e.g., leisure, commerce, fishing) [24-28]. Those beaches characterized by the presence of reefs near to the coastline that forming tides pools and they have provided a nice environment to different types of fishers [29]. Those reefs act as a natural protection for the coastline on these beaches, which very affected by coastal erosion, dissipating the waves’ energy, and represent one of the great marine biodiversity hotspots in Northeast Brazil [30-32].

Data collection

We used a semi-structured questionnaire to interview the fishers on the beaches. Each questionnaire had 26 questions about the social profile, resource dependence level, diversity of beaches, fisher gears, habits and environmental pollution perception caused by the wrong disposal of solid waste and sewage. A minimum sample number of 455 questionnaires was estimated by the finite difference method [33] based on the population of recreational fishers at those beaches. The fishers were randomly select on the beaches and asked if they agreed to ask this interview.

Data Analysis

The data collected was analysis according to the social profiles and the fishing type described, and the environmental perception of each fisher interviewed. The social profile described according to the age, how many times they are in the fishing activity, and schooling. The fishers were divided according to fishing locations (beach or far from the coast), gears and target species. The fishers’ environmental quality perception assessed by a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [34]. Proportions equal or higher than 70% were accept. The results plotted as a two-dimensional plot the formation of groups regarding the Euclidean distance of the variables could observed. We also analyzed the catch yield and the catch per unit effort (CPUE) for the dry and rainy seasons. The catch yield for each season was analysis according his significantly (p<0.05). The CPUE was estimate according to the formula U=C/f where C = total catch expressed in kilograms and f = the number of reported fishing in each year [35].

Results

We interviewed 170 recreational fishers from October 2016 to May 2017. The questionnaire structured in three sections: (i) socioeconomic profile, (ii) catch yield and (iii) environmental perception. The interviews conducted according to the laws that regulate human subject research in Brazil (Process No. 62425716.0.0000.5207).

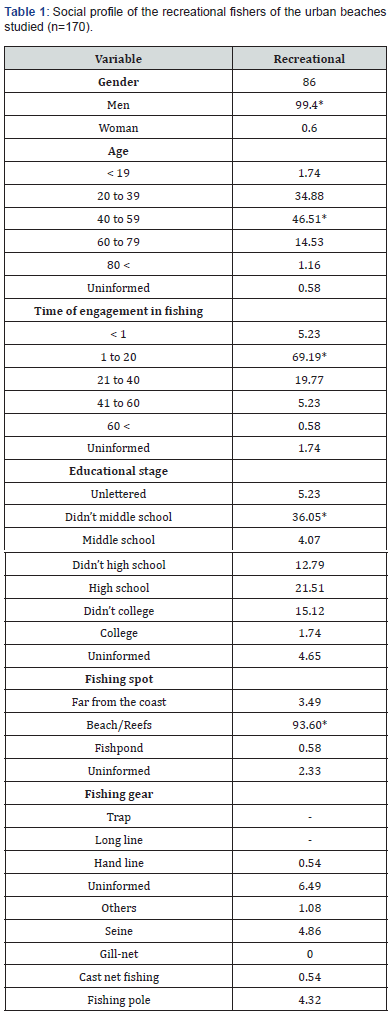

Profile of Interviewees and the Activity in Urban Beaches

The socioeconomic profile of the activity described (Table 1). Women were a minority in the sample. The average age was 45.7 years (SD = 13.3) for men and 39 years (DP=1) for women. The most frequent interval was sample were 40 to 59 years old, which was the most frequent interval for both groups. The older recreational fisher was 81 years and younger was 17. On average, the time of engagement in fishing varied form the first day to 70 years. The interval from one to 20 years was more frequent, corresponding to 69.2% of time of engagement in fishing for the recreational fishers.

*Higher values found for each by fisher group

Concerning the educational stage, the recreational fishers, and 34.9% claimed that they graduated from high school; followed by 20.6% that did not graduate from middle school, from which 97.2% are male fishers and 2.8% female fishers; and 13.7% have a Higher Education degree. About 4.6% of the recreational fishers did not answer their educational stage. All female recreational fishers claimed that they did not graduated from middle school. Beach fishing was most common among the recreational fishers interviewed. 2.3% of recreational fishers did not answer where they usually fish. Among the fishing gears used, fishing pole (82.2%), hand line (6.5%) and others (e.g., landing net, manual suction gun, gaff) (4.9%) were the most mentioned gears.

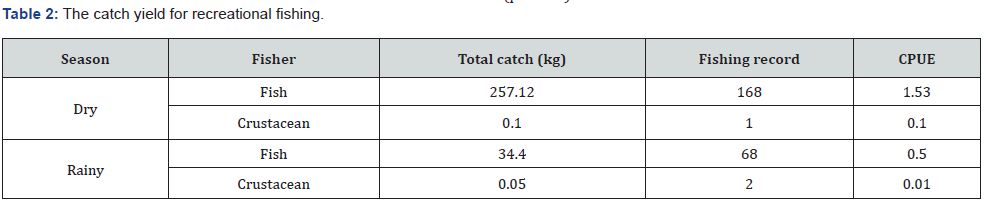

Catch Yield

The yield (in kilograms) by the recreational fisheries described below (Table 2). The number of recreational fisheries was significantly higher (p <0.05) in the dry season than in the rainy season (p<0.05). The volume captured by recreational fishing in the dry season was also higher than in the rainy season (p <0.05).

Environmental Quality Perception

61% by recreational fishers think the beaches became more pollute over the last two decades, 25% did not notice any changes over the last 20 years, 2.3% claimed that they think the beaches are less polluted and 11.7% did not answer that question. Around 78.5% of the recreational fishers believe that pollution is responsible for the loss of diversity and biomass of marine fish and crustacean species in the beaches studied. For 73.2% of these fishers claimed that recreational activities (e.g., bathing, sports activities in the foreshore zone, etc.) do not have an impact on fishing. More than a half of the recreational fishers (52.3%) claimed that the urbanization process of the beaches has not affected fishing.

To the fishers who did notice some influence of the urbanization of the beaches on fishing, the enlargement of Piedade and Candeias beaches mentioned by 43.5% of the recreational fishers as the cause of impact. The second most mentioned cause was pollution, which corresponds to 25% of the responses. The trash catches during fishing mentioned by 86.6% of the recreational fishers. Plastic items were the most caught: 80.5% of the cases for the recreational fishers. Plastic bags were the most mentioned item (71.1%).

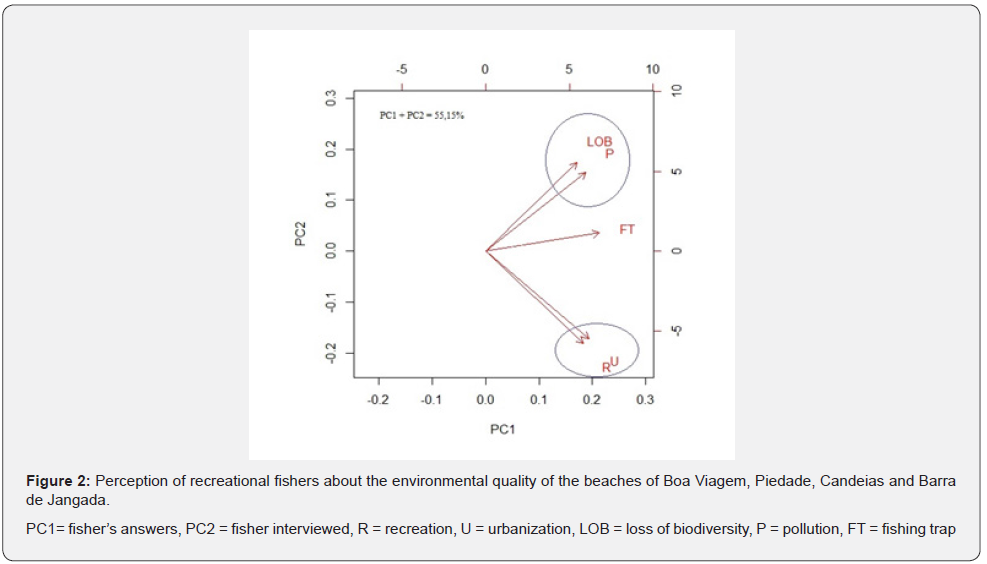

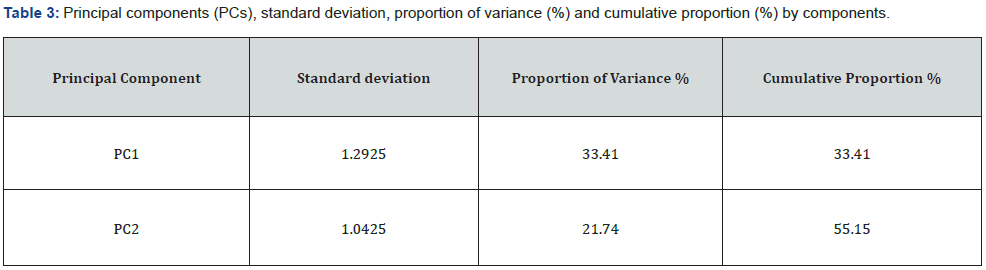

The Principal Component Analysis showed that for the recreational fishers three sets found for four explainable variances (Figure 2). For that group, biodiversity and biomass loss is associated with the pollution of the beaches over time whereas recreational practices are associated with the urbanization of the beaches and adjacent areas. The catch of waste materials suggested being associated with none of the variances. Those results are explainable for (PC1 + PC2) 55.15% of the accumulated variance (Table 3,4); therefore, they are not representative to explain the environmental perception of the recreational fishers surveyed [34].

Discussion

Interviews through questionnaires showed an excellent method for data collecting to environmental perception and environmental belonging [36]. This approach model has become frequent in similar studies nowadays, like in the articles by Silvano & Begossi [37], Santos et al. [38], Tonin & Lucaronni [20], Rodella & Corbau [39], Silvano & Hallwas [14], etc.

Recreational Urban Fisher’s Profile

In urban coastal the recreational fishers usually outnumber the commercial fishers or may even be the only fishers found in those places [40]. The knowledge of the fishing strategies and fishing spots chosen by these fishers can contribute substantially to an effective monitoring of the impacts of fishing on local biodiversity, but despite its importance, it is still little studied. This paper can contribute to the knowledge of the fishing strategies of recreational urban fisher, identifying what most of these fishers prefer to fish in the beach or under the reefs, those that fished far from the beach, the displacement had been made with small boats (e.g., boats, rafts) owned or rented.

We could also note that some recreational fishers who own rafts usually leave them on the beach sand near professional fishing vessels, and that a same recreational fisher could own more than one raft. A small percentage of women found fishing in the course of this study, and this is due to the predominance of men in fishing activities [41,42]. The engagement of women is better described small-scale commercial fishing than recreational fishing, and it is considered quite heterogenic, in which the catch of crustaceans and mollusks stand out (“marisqueiras”), which is usually performed in mangrove swamps, and also in indirect activities such as profiting and commerce [43,44].

We could observe that those women were not so strongly engaged in fishing, even if for recreation, as men were. To those women recreational fishing was more attractive as a way of being around their family in these recreational practices than an activity they would spontaneously engage in. To Diamond et al [45], women have a more restrict knowledge of biodiversity and hence perception of the environmental quality than men. According to the author, this is because women deal more indirectly with natural resources. That trend could observe in this research. To women recreational fishers, fishing was a way to be around or follow their husbands, so their perception minimally related to the information their partners would comment about species and environmental conditions.

Environmental Perception

Landscape changes

The landscape alterations from the last decades in areas near the beaches studied were one of the main reasons for the negative perception by the recreational fishers. In big cities’ coastal areas, like Recife and Jaboatão dos Guararapes, changes near and in the shore, zones are quite usual and cause evident effects on the marine environment, such as changes in the structure of algae, fish and crustaceans’ communities [46-48]. To the recreational fishers in this study, the enlargement performed in the shore zones of Candeias and Piedade beaches was the landscape alteration that caused the worst discontent due to its negative impacts on the local marine biodiversity.

The enlargement of shore zones is usual practice in urban beaches performed mainly to mitigate the effects of coastal erosion caused by the rising of the sea level and by the disorganized population growth in areas adjacent to the beaches with a tendency to construct building closer and closer to the coast [48,49]. The enlargement by Piedade and Candeias beaches went make in 2013 to restore the sand zone destroyed by the erosive processes caused by the civil construction very close to the high tide limits [50]. However, the fishers approached said that the enlargement of the beach resulted to siltation and sand covering of the fish zones in each beach and also in Boa Viagem and Barra de Jangada beaches, as an outcome of the waves and marine tides being carried out [51,52].

Due to the covering some biodiversity hotspots have been destroyed making then common species like the Tainha (Mugil sp.) move to zones farther from the coast or have had their populations decreased like the Corrupto (C. major), resulted to a decrease in the fishing income in those beaches. Furthermore, the enlargement of Piedade and Candeias beaches made them more attractive to recreational users, which led to an increase the amount of solid waste materials left on shore and oceanic zones making the beaches more polluted.

Pollution

Pollution was another negative impact often reported by the recreational fishers during the interviews. Although questions about pollution was make: (I) if it was responsible for the biodiversity loss and (II) how the current pollution level of the beach are compared to when one had started fishing. Pollution also mentioned as an outcome of the urbanization. No association between the three answers reported. That is if to a recreational fisher who believed pollution are responsible for the biomass and biodiversity loss in the beaches, pollution cannot relate to the urbanization. Association between answers could expected.

However, it should be highlighted that pollution on the beaches is evident, but an interviewed fisher might start fishing at that place when it was already polluted, as well as they might believe the pollution found was not so harmful to cause biomass and biodiversity loss of the existing species there. Pollution is the outcome of human activities that hardest affects the marine environmental quality mostly in urban marine areas and is one of the main adversities to the well-being of beach users [53]. The pollution result is biomass and biodiversity loss [54], and therefore, these areas need management measures to fight pollution and its effects to the coastal environment.

Another factor that reflects on the high pollution of those beaches is the frequent catch of solid waste (mainly plastic bags) by the recreational fishers interviewed. Plastic items were as the main components of the solid waste in the sea and already been listed as the main items found in the foreshore zone of Boa Viagem beach [28, 53-55]. Although there is no case study with deeper details on the issue, plastic bags are also very common in recreational fishing in Piedade, Candeias and Barra de Jangada beaches.

The main sources of plastic waste materials in the marine environment are the rivers which transport waste materials thrown along its stream in the continent [38], but many authors indicate fishing activities as a significant source of marine plastic pollution [56-60]. Nevertheless, the fishers answered showed didn’t leave plastic waste on this beach suggested a major part of the plastics found on this beaches might relate to the city surface runoff and to improper discard of waste materials by other beach users, summer migrants, and commerce, rather than to fishing waste left in the ocean [61].

Furthermore, many fishers said they collaborate with the adequate removal and discard of plastic items found on the beaches and in the ocean or when accidentally caught during fishing, in order to better the landscape look and clean aspect and minimize the damaging effects of those items to the environment. Plastic represents an overwhelming threat to marine biodiversity because they are extremely easy to eat or stuck in the animals’ bodies [62-66]. For the fishes, especially small-sized species or reef fishes, the highest possibility with a direct impact concerning plastics is ingestion [67-68].

In this research, no case of fishes caught with plastic items attached to their bodies or inside their stomach been mentioned; however, it known by the fishers approached in this research that attachment or ingestion cases exist and that this is responsible for the death of many individuals. Plastic bags, which were the items most, mentioned as caught by the fishers approached, are among the marine plastics that are most harmful to fishes [69,70]. It is estimated that, from the marine species which are most threatened by the accumulation of plastics in the coastal and oceanic zones, 10% are mentioned in the IUCN’s red list of endangered species, such as Caranha and the Sirigado, mentioned in this study and which are listed as vulnerable in the red list [71,72].

Although for most species mentioned in this study the ingestion of plastic bags may be impossible due to the bags’ size being almost proportional to the species described. Overtime these plastic bags shatter into smaller pieces as an outcome of physical and chemical processes getting to smaller sizes, which can be, eat [73,74]. Besides the negative impacts on the marine biota the accumulation of solid waste materials along the coastal zones causes negative aesthetical impacts and may even result in lack of exploratory and recreational interest in that area [70,75,76]. The beaches studied for this research, despite the biological and aesthetical impacts caused by the accumulation of solid waste materials, are still quite attended [77,78].

The intense use of these beaches does not characterize lack of comprehension on the advanced stage of pollution at which they are. However, this intense use can be justified by its morphological characteristics, which grant them some great fame around its natural beauty and by its easy access due to the urban location of these beaches. This set of factors make those beaches very attractive for practicing many activities, among which we point out fishing.

Recreational Fishing Seasonality and Yield

The seasonality of recreational fishing in the beaches studied been related to the dry season (September and February) and the rainy season (March to August) in Northeast Brazil. The number of fisheries and the amount of catch reported was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the dry season compared to the rainy season for recreational fishing. On the dry and rainy seasons occur changes in the rainwater input in the sea. Causing a shift in the sea temperature and the salinity dynamics [79]. This change results in an unfavorable the presence of some species, such as the Tainha (Mugil sp) or the Xaréu (Caranx sp) in the fishing spot, resulting in a superior or inferior catch [80].

Shifts in the presence of target species in fishing locations is a traditional knowledge among recreational fishers, justifying a greater presence of these fishers in the dry season than in the rainy season [80]. During dry season, recreational fish was less frequent only in the holiday from the Christmas and the Carnival. In Recife and Jaboatão dos Guararapes cities, are usual to celebrate these holidays in the beaches studied. Many big structures are constructing in the sand zone beach, restricting to access for the fishers. During these holidays, more wastes discarded on the beaches, making the beaches fewer attractive to the fishers. During the rain seasons, we could observe that as the rain would become longer, the number of fishers found fall. Many days nobody fisher was found at the studied beaches.

In this sense because in rainy days few fishers go fish because is the mobility is harder in rainy days in this city. In addition, because sometimes the supply of rainwater is unfavorable for fishing [80]. In 2017, the rainy season in Recife and Jaboatão dos Guararapes was more intense than usual. The precipitation index was around 7.75% higher than the historical average [81]. This rainfall intensity and frequency contributed to the reduction of fishing and the catch in the studied rain season. However, there is no recent registry of fishing and catch in the studied beaches in others rain seasons. This fact difficult a more detailed inference and discussion about it [82-109].

Conclusion

Recreational fishers act city beaches from Pernambuco. The recreational fishers in those beaches are male-dominated activities and the participation of women is associated to be with their family. Therefore, the sensitivity of perceiving changes in the environment is greater for men, while the perception of women is often subject to the information passed on by their companions. The urban beaches that present coral reefs and sandstone reefs work as fishing hotspots that explore the reefs biodiversity and depend on the environment’s good quality. However, the environmental quality of those beaches is not satisfying for the group of recreational fishers.

The main causes of disgust are the shifts in the physical dynamics of the beaches due to the enlargement of Piedade to Candeias beaches and the pollution, which highlighted by the commercial fishers also by the recreational fishers. However, despite the negative aspects approached, those fishers keep on attending and fishing in those beaches. The intensity of recreational fishing activities on the city beaches are dependent on seasonal variations due to dry and rainy seasons. The variations significantly influence on the amount caught because of the reduction of the effort made. In dry seasons, the fishing activities at those beaches reduce during the year-end celebrations and during Carnival. Therefore, more studies are necessary to track the seasonality of fishing actives over the years in the Boa Viagem, Piedade, Candeias and Barra de Jangada beaches.

References

- McPhee DP (2017) Urban recreational fisheries in the Australian Coastal Zone: the sustainability challenge. Sustainability 9: 1-12.

- McPhee DP, Hundloe TJA (2004) The role of expenditure studies in the (mis)allocation of access to fisheries resources in Australia. Australasian Journal Environmental Management 11: 34-41.

- McPhee D (2008) Fisheries Management in Australia. In: Federation Press: Annandale, Australia.

- National Research Council (2006) Review of recreational fisheries survey methods. The National Academy of Sciences, Washington.

- Pawson MG, Glenn H, Padda G (2008) The definition of marine recreational fishing in Europe. Marine Policy 32: 339-350.

- Pollock KH, Jones CM, Brown TL (1994) Anglers’ Survey Methods and their Application in Fisheries Management. American Fisheries Society Special Publications 25: 378-380.

- Coleman FC, Figueira WF, Ueland JS, Crowder LB (2004) The impact of United States recreational fisheries on marine fish populations. Science 305: 1958-1960.

- Cooke SJ, Cowx IG (2004) The role of recreational fishing in global fish crises. Bioscience 54: 857-859.

- Lewin WC, Arlinghaus R, Mehner T (2006) Documented and potential biological impacts of recreational fishing: insights for management and conservation. Reviews in Fisheries Science 14: 305-367.

- McPhee D (2011) The management of recreational fisheries. In: Gullett W, Schofield C, Vince J (eds.) Marine Resources Management, LexisNexis: Chatsworth, Australia.

- Tunca S, Aydin M, Karapiçak M, Lindroos M (2018) Recreational fishing along the Middle and Eastern Black Sea Turkish coasts: biological, social and economics aspects. Acta Adriatica 59(2): 191-206.

- Young MA, Foale S, Bellwood DR (2016) Why do fishers’ fish? A cross-cultural examination of the motivations for fishing. Marine Policy 66: 114-123.

- Begossi A, Salyvonchyk S, Glamuzina B, Souza SP, Lopes PMF, et al. (2019) Fishers and groups (Epinephulus marginato and morio) in the coastal of Brazil: integrating information for conservation. Journal of Ethinobiology and Ethnomedicine 15(53): 1-26.

- Silvano RAM, Hallwas G (2020) Participatory Research with Fishers to Improve Knowledge on Small-Scale Fisheries in Tropical Rivers. Sustainability 12: 1-24.

- Alves RRN, Souto WMS (2015) Ethnozoology: a brief introduction. Ethnobiology and Conservation 4(1): 1-13.

- Jefferson RL, Bailey I, Laffoley D, Richards JP, Attrill MJ (2014) Public perceptions of the UK marine environment. Marine Policy 43: 327-337.

- Leite DSL, Vasconcelos ERTPP, Riul P, Freitas NDA, Miranda GEC (2020) Evalution of the conservation status and monitoring proposal for the coastal reefs of Paraíba, Brazil: Bioindication as an environmental management tool. Ocean and Coastal Management 194: 1-17.

- Schultz PW (2011) Conservation means behaviour. Conservation Biology 25(6): 1080-1083.

- Silva MRO, Lopes PFM (2015) Each fisherman is different: Taking the environmental perception of small-scale fishermen into account to manage marine protected areas. Marine Policy 51: 347-355.

- Tonin S, Lucaroni G (2017) Understanding social knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards marine biodiversity: The case of tegnùe in Italy. Ocean & Coastal Management 140: 58-78.

- Leleu K, Alban F, Pelletier D, Charbonnel E, Letourneur Y, et al. (2012) Fishers' perceptions as indicators of the performance of Marine protected areas (MPAs). Marine Policy 36: 414-422.

- Evangelista-Barreto NS, Daltro ACS, Silva IP, Bernades FS (2014) Indicadores socioeconômicos e percepção ambiental de pescadores em São Francisco do Conde, Bahia. Boletim do Instituto de Pesca 40(3): 459-470.

- Engel MT, Marchini S, Pont AC, Machado R, de Oliveira LR (2014) Perceptions and attitudes of stakeholders towards the wildlife refuge of Ilha dos Lobos, a marine protected area in Brazil. Marine Policy 45: 45-51.

- Smith RA (1991) Beach resorts: a model of development evolution. Landscape and Urban Planning 21(3): 198-210.

- Souza ST (2004) A saúde das praias da Boa Viagem e do Pina, Recife (PE). Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

- Costa MF, Araújo MCB, Silva-Cavalcanti JS, Souza ST (2008) Verticalização da Praia de Boa Viagem (Recife, Pernambuco) e suas Consequências Sócio-Ambientais. Revista da Gestão Costeira Integrada 8(2): 233-254.

- Cavalcanti EAH, Neumann-Leitão S, Vieira DAN (2008) Mesozooplâncton do sistema estuarino de Barra das Jangadas, Pernambuco, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 25(3): 436-444.

- Dias Filho MJO, Araújo MCB, Silva-Cavalcanti JS, Silva ACM (2011) Contaminação da praia de Boa Viagem (Pernambuco-Brasil) por lixo marinho: relação com o uso da praia. Arquivos de Ciências do Mar 44(1): 33-39.

- Santos AA, Cocentino AMM, Reis TNV (2006) Macroalgas como indicadoras da qualidade ambiental da praia de Boa Viagem – Pernambuco, Brasil. Boletim Técnico-Científico do CEPENE 14(2): 25-33.

- Pereira SMB (2002) Desenvolvimento e situação atual do conhecimento das macroalgas marinhas das regiões Norte e Nordeste. In: Araújo EL, Moura AN, Sampaio EVSB, Gestinari LMS, Carneiro JMT (Eds.) Biodiversidade, conservação e uso sustentável da flora do Brasil, Editora Universitária, Recife, Pp. 117-121.

- Pereira SMB, Oliveira-Carvalho MF, Angeiras JAP, Bandeira-Pedrosa ME, Oliveira NMB, et al. (2002) Algas marinhas bentônicas do estado de Pernambuco. In: Tabarelli M, Silva JMC (eds.) Diagnóstico da biodiversidade de Pernambuco Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio Ambiente, Recife Pp.97-124.

- Mendonça F, Gonçalves R, Awange J, Da Silva L, Gregório M (2014) Temporal shoreline series analysis using GNSS. Boletim de Ciências Geodésicas 20(3): 701-719.

- Richardson RJ (2007) Pesquisa social: métodos e técnicas. In: (3rd ) Atlas, São Paulo.

- Valderrama L, Paiva VB, Marco PH, Valderrama P (2016) Proposta experimental didática para o ensino de análises de componentes principais. Química nova 39(2): 245-249.

- Petrere Jr M (1978) Pesca e esforço de pesca no Estado do Amazonas. I. Esforço e captura por unidade de esforç Acta Amazonica 8(3): 439-454.

- Reilly K, O Hagan AM, Dalton G (2016) Moving from consultation to participation: A case study of the involvement of fishermen in decisions relating to marine renewable energy projects on the island of Ireland. Ocean & Coastal Management 143: 30-40.

- Ramires M, Clauzet M, Rotundo MM, Begossi A (2012) A pesca e os pescadores artesanais de Ilhabela (SP), Brasil. Boletim do Instituto de Pesca 38(3): 231-246.

- Schmidt C, Krauth T, Klöckner P, Röme M, Stier B, et al. (2017) Estimation of global plastic loads delivered by rivers into sea. EGU General Assembly 19: 12171.

- Rodella I, Corbau C (2020) Linking scenery and users’ perception analysis of Italian beaches (cause studies in Veneto, Emilia-Romagna and Basilicata regions). Ocean and coastal management 183: 1-15.

- McPhee DP, Leadbitter D, Skilleter GA (2002) Swallowing the bait: Is recreational fishing in Australia ecologically sustainable? Pacific Conservation Biology 8: 40-51.

- Sharma C (1996) Different voices, similar concerns. Samadura Report 15: 46-49.

- Barella W, Ramires M, Rotundo MM, Petrere M, Clauzete M, et al. (2016) Biological and socio-econimic aspects of recreational fisheries and their implications for the management of coastal urban areas of south-eastern Brazil. Fisheries Management and Ecology 23: 303-314.

- Di Ciommo RC, Schiavetti A (2012) Women participation in the management of a Marine Protected Area in Brazil. Ocean & Coastal Management 62: 15-23.

- Pedrosa BMJ, Lira L, Maia ALS (2013) Pescadores urbanos da zona costeira do estado de Pernambuco, Brasil. Boletim do Instituto de Pesca 39(2): 93-106.

- Diamond NK, Squillante L, Hale L (2003) Cross currents: navigating gender and population linkages for integrated coastal management. Marine Policy 27: 325-331.

- Toft JD, Ogston AS, Heerhartz SM, Cordell JR, Flemer EE (2013) Ecological response and physical stability of habitat enhancements along an urban armored shoreline. Ecological Engineering 57: 97-108.

- Munsch SH, Cordell JR, Toft JD, Morgan EE (2014) Effects of seawalls and piers on fish assemblages and juvenile salmon feeding behavior. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 34: 814-827.

- Munsch S H, Cordell JR, Toft JD (2015) Effects of shoreline engineering on shallow subtidal fish and crab communities in an urban estuary: A comparison of armored shorelines and nourished beaches. Ecological Engineering 81: 312-320.

- Bulleri F, Chapman MG (2010) The introduction of coastal infrastructure as a driver of change in marine environments. Journal of Applied Ecology 47(1): 26-35.

- Marques AKCS, Malinconico N, Farias PCS, Silva AV, Silva DA, et al. (2014) Estudos prospectivos dos impactos ambientais decorrentes do projeto de engorda da costa das praias de Jaboatão dos Guararapes (PE). Natural Resouces 3(2): 37.

- Rollnic M, Medeiros C (2006) Circulation of the Coastal Waters off Boa Viagem, Piedade and Candeias Beaches Pernambuco, Brazil. Journal of Coastal Research 39: 648-650.

- Rollnic M, Medeiros C (2013) Application of a probabilistic sediment transport model to guide beach nourishment efforts. Journal of Coastal Research 65: 1856-1861.

- Ferdinando G, Elliff CI, Silva IR, Brito TS, Bittencourt ACSP (2016) Plastic fragments as a major component of marine litter: a case study in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Journal of Integred Coastal Management 16(3): 281-287.

- Leite AS, Santos LL, Costa Y, Hatje V (2014) Influence of proximity to an urban Center in the pattern of contamination by marine debris. Marine Pollution Bulletin 81(1): 242-247.

- Silva JS, Leal MMV, Araújo MCB, Barbosa ST, Costa MF (2008) Spatial and temporal patterns of use of Boa Viagem beach, Northeast Brazil. Journal of Coastal Research 24: 79-86.

- Possato FE, Barletta M, Costa MF, Ivar do Sul JA, Dantas DV (2011) Plastic debris ingestion by marine catfish: an unexpected fisheries impact. Marine Pollution Bulletin 62: 1098-1102.

- Waluda CM, Staniland IJ (2013) Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals at Bird Island, South Georgia. Marine Pollution Bulletin 74: 244-252.

- Ryan PG (2020) The transport and fate of marine plastics in South Africa and adjacent oceans. Marine Plastic Debris 116(5/6): 1-9.

- Reisser J, Shaw J, Wilcox C, Hardesty BD, Proietti M, et al. (2013) Marine Plastic Pollution in Waters Around Australia: Characteristics, Concentrations, and Pathways. Plos One 8(11): 80466.

- Pettipas S, Bernier M, Walker TR (2016) A Canadian policy framework tomitigate plastic marine pollution. Marine Policy 68: 117-122.

- Silva JS, Araújo MCB, Costa MF (2009) Plastic litter on an urban beach – a case study in Brazil. Waste Manag Res 26: 1-5.

- Gregory MR (2009) Environmental implications of plastic debris in marine settings—entanglement, ingestion, smothering, hangers-on, hitch-hiking and alien invasions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364: 2013-2025.

- Costa MF, Ivar do Sul JA, Spengler A, Silva-Cavalcanti JS, Araújo MCB (2010) Pellets and plastic fragments on the strandline: snapshot of a Brazilian beach. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 168: 299-304.

- Araújo M C B,Silva Cavalcanti JS (2014) Lixo nas praias e no mar: o que temos a ver com isso??? Ciência Hoje 313: 26-30.

- Eerkes-Medrano D, Thompson RC, Aldridge DC (2015) Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Research 75: 63-82.

- Araújo M C B,Silva Cavalcanti JS (2016) Dieta indigesta: milhares de animais marinhos estão consumindo plásticos. Revista Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade 10: 74-81.

- Ferreira GV B, Barletta M, Lima A RA, Dantas DV, Justino AKS, et al. (2016) Plastic debris contamination in the life cycle of Acoupa weakfish (Cynoscion acoupa) in a tropical estuary. ICES Journal of Marine Science 74: 108.

- UNEP (2016) Marine Plastic Debris and Microplastics – Global Lessons and Research to Inspire Action and Guide Policy Change. Nairobi, United Nations Environment Programe.

- Besseling E, Foekema EM, Van Franeker JA, Leopold MF, Kühn S, et al. (2015) Microplastic in a macro filter feeder: humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae. Marine Pollution Bulletin 95(1): 248-252.

- Hardesty BD, Good TP, Wilcox C (2015) Novelmethods, new results and science-based solutions to tackle marine debris impacts on wildlife. Ocean & Coast Management 115: 4-9.

- Gall SC, Thompson RC (2015) The impact of debris on marine life. Marine Pollution Bulletin 92(1-2): 170-179.

- Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (2016) Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasí

- Thompson RC, Olsen Y, Mitchell RP, Davis A, Rowland SJ, et al. (2004) Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science 304: 838.

- Davidson TM (2012) Boring crustaceans damage polystyrene floats under docks polluting marine waters with microplastic. Marine Pollution Bulletin 64: 1821-1828.

- Sivan A (2011) New perspectives in plastic biodegradation. Current Opinon in Biotechnology 22(3): 422-426.

- Jang YC, Hong S, Lee J, Lee MJ, Shim WJ (2014) Estimation of lost tourism revenue in Geoje Island fromthe 2011 marine debris pollution event in South Korea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 81(1): 49-54.

- Silva JS, Barbosa SCT, Leal MMV, Lins AR, Costa MF (2006) Ocupação da praia de Boa Viagem (Recife –PE) ao longo de dois dias de verão: um estudo preliminar. Pan-American Journal of Aquatic Sciences 1(2): 91-98.

- Silva JC, Leal MMV, Araújo MCB, Barbosa SCT, Costa MF (2008) Spatial and temporal patterns of use of Boa Viagem beach, Northeast Brazil. Journal of Coastal Research 24(4): 890-898.

- Silva LA (2015) Com o vento a lagoa vira mar: uma etnoarqueologia da pesca no litoral norte do RS. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 10(2): 537-547.

- Mourão JS, Nordi N (2006) Pescadores, peixes, espaço e tempo: uma abordagem etnoecoló Interciência 31(5): 358-363.

- APAC – Agência Pernambucana de Águas e Climas (2017) Boletins Climá Recife, Governo do Estado de Pernambuco.

- Allison E H, Ellis F (2001) The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 25: 377-388.

- Arthur C, Baker J, Bamford H (2009) Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic. Marine Debris 9-11: 2008.

- Beaumont NJ, Austen MC, Mangi SC, Townsend M (2008) Economic valuation for the conservation of marine biodiversity. Marine Pollution Bulletin 56(3): 386-396.

- (2006) Board, Ocean Studies, and National Research Council. Review of Recreational Fisheries Survey Methods. National Academies Press, US.

- Regulamenta a pesca da lagosta (Panulirus laevicauda e Panulirus argus) em águas jurisdicionais brasileiras. Brasília: 03 de janeiro de 2007. Instrução Normativa nº144, de 03 de janeiro de 2007, Brasil.

- Browne MA, Galloway TS, Thompson RC (2010) Spatial patterns of plastic debris along estuarine shorelines. Environmental Science and Technology 44(9): 3404-3409.

- Carneiro AMM, Diegues ACS, Vieira LFS (2014) Extensão participativa para a sustentabilidade da pesca artesanal. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 32: 81-99.

- Clause S (1998) Applied correspondence analysis: an introduction. 121.

- Diegues AC (1988) Pesca artesanal no litoral brasileiro: cenários e estratégias para sua sobrevivência. Instituto Oceanográfico, São Paulo.

- Eastwood EK, Clary DG, Melnick DJ (2017) Coral reef health and management on the verge of a tourism boom: A case study from Miches, Dominican Republic. Ocean & Coastal Management 138: 192-204.

- FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2004) The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA). United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, Roma.

- FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2012) The World State of Fishery and Aquaculture. United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, Roma.

- Ferreira EM, Lopes IS, Pereira LCR, Costa FN (2014) Qualidade microbiológica do peixe serra (Scomberomerus brasiliensis) e do gelo utilizado na sua conservaçã Arquivo do Instituto Biológico 81(1): 49-54.

- França AR, Olavo G (2015) Indirect signals of spawning aggregations of three commercial reef fish species on the continental shelf of Bahia, east coast of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography 63(3): 289-302.

- Gomes AS, Ferrete H, Cecílio IS, Freitas RR (2017) Análise organizacional e gestão de estoques em peixarias no norte do Espírito Santo. Brazilian Journal of Production Engineering 3(1): 57-65.

- Instituto Oceanário (2006) Diagnóstico socioeconômico da pesca artesanal do litoral de Pernambuco.

- Leal MMV (2006) Percepção dos usuários quanto à erosão costeira na praia da Boa Viagem, Recife (PE), Brasil. 108p. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife.

- Lucchetti M, Corsonello A, Gattaceca R (2008) Environmental and social determinants of aging perception in metropolitan and rural areas of Southern Italy. Archives of Geontology and Gearitrics 46: 349-347.

- Marques S, Ferreira BP (2010) Composição e características da pesca de armadilhas no litoral norte de Pernambuco – Brasil. Boletim Técnico-Científico do CEPENE 18(1).

- Ngoran SD, Xue X (2017) Public sector governance in Cameroon: A valuable opportunity or fatal aberration from the Kribi Campo integrated coastal management? Ocean & Coastal Management 138: 83-92.

- Pinto MF, Mourão JS, Alves RRN (2013) Ethnotaxonomical considerations and usage of ichthyofauna in a fishing community in Ceará State, Northeast Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 9(1): 1-11.

- Purcell SW, Pomeroy RS (2015) Driving small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Frontiers in Marine Science 2: 1-7.

- Robins CR, Ray GC (1986) A field guide to Atlantic coast fishes of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

- Rocha LA, Lindeman KC, Rocha CR, Lessios HA (2008) Historical biogeography and speciation in the reef fish genus Haemulon (Teleostei: Haemulidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48: 918-928.

- Salas S, Chuenpagdee R, Seijo J C, Charles A (2007) Challenges in the assessment and management of small-scale fisheries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Fisheries Research 87: 5-16.

- Salas S, Gaertner D (2004) The behavioural dynamics of fisheries: management implications. Fish and Fisheries 5: 153-167.

- Slavin C, Grage A, Campbell ML (2012) Linking social drivers of marine debris with actual marine debris on beaches. Marine Pollution Bulletin 64(8): 1580-1588.

- Wright SL, Thompson RC, Galloway TS (2013) The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: a review. Environmental Pollution 178: 483-492.