Women in West African Mangrove Oyster (Crassostrea Tulipa) Harvesting, Contribution to Food Security and Nutrition in Ghana

Hayford Agbekpornu*, Effah Joseph Ennin, Fuseina Issah, Abednego Pappoe and Richard Yeboah

Fisheries Commission, Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, Ghana

Submission:May 15, 2021; Published:July 09, 2021

*Correspondence author: Hayford Agbekpornu, Fisheries Commission, Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, Ghana

How to cite this article:Hayford A, Effah J E, Fuseina I, Abednego P, Richard Y. Women in West African Mangrove Oyster (Crassostrea Tulipa) Harvesting, Contribution to Food Security and Nutrition in Ghana. Oceanogr Fish Open Access J. 2021; 14(1): 555878 DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2021.14.555878

Abstract

Declining marine fish stocks have severe effects on the livelihoods of small-scale coastal fishing communities. As a result, the development of additional livelihoods in oyster production has become appropriate as a way of improving incomes and nutrition, reducing hunger, and creating employment among women. Oysters are rich in essential vitamins and minerals such as protein, omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, zinc, iron, and vitamins B and E, and pose no risk to human cholesterol levels. The objective of this study is to examine Crassostrea tulipa harvesting in Ghana by women and its contribution to food security and nutrition. Data was collected from Bortianor, Tetegu, Tsokome, and Faana communities along the Densu Delta in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana using the Kobo Toolbox. A total of a hundred (100) harvesters were sampled for the study.

Findings showed that the youth and elderly are into oyster production with years of experience of harvesters ranging from 1 to 40 years (average of 13 years). Most oyster harvester (69%) have basic level of education. Settlers are mostly involved in oyster activities (79%) and family members are involved in oyster harvesting. Oyster activities is not the main source of income of most of the women sampled (70%). The proportion of income from oyster activities forms an average of 45% of total household income. All respondents sold oyster meat to consumers in the steamed form (100.0%) and 30% sold oyster shells to companies and individuals to be used as ballaster for road and poultry grit lime flour (animal feed) among others. The oyster business is a profitable venture with a simple and short supply chain (Vertically Integrated). Some of the co-management policies implemented in the communities included closed season. Inadequate protective working gear, inadequate harvesting tools (e.g., shoes, snickers, knives), high hiring cost of boat/canoes, and wounds from cuts on part of the body during harvesting are some challenges affecting the women in the sector.

Keywords: West African Mangrove Oyster; Crassostrea tulipa; Harvesting; Ghana

Introduction

Human societies face enormous challenges of having to provide food and livelihoods to a population of well over 9 billion people by the middle of the twenty-first century while addressing the disproportionate impacts of climate change and environmental degradation on the resource base. Food and agriculture are key to achieving the entire set of SDGs, and many SDGs are directly relevant to fisheries and aquaculture SDG 14 (Conserve and sustainably use of oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development) [1]. Declining marine fish stocks have severe effects on the livelihoods of small-scale coastal fishing communities. As a result, the development of additional livelihoods in oyster production has become relevant as a way ofimproving incomes and nutrition, reducing hunger, and creating employment. According to Hayes and Lauden [2], oysters have very high essential vitamins and minerals such as protein, omega three fatty acids, calcium, zinc, iron, vitamins B and E and pose no danger to the cholesterol levels in human.

The fisheries and aquaculture sector are crucial to improving food security and human nutrition and has an increasingly important role in the fight against hunger, as articulated in the 2030 Agenda. People have never consumed as much fish as they do today, with per capita global fish consumption doubling since the 1960s [1]. The per capita consumption of fish in Ghana ranges between 20 to 25kg [3]. Millions of people around the world including Ghana find a source of income and livelihood in the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. It is estimated that 10% of the populace in Ghana are involved in the fisheries and aquaculture value chain. Women play a significant role in fisheries and aquaculture activities. Official statistics indicate that 59.6 million people were engaged on a full-time, part-time, or occasional basis in the primary sector of capture fisheries and aquaculture in 2016 out of which 19.3 million were in aquaculture and 40.3 million in capture fisheries. It is estimated that about 14% of these workers were women as compared with an average of 15% across the period of 2009-2016.

The decrease could be partially ascribed to decreased sex-disaggregated reporting [1]. In Africa, it is reported that 11% of the total labour force is employed in the fisheries sector [4]. Currently, no official statistics are depicting the percentage of women in the fisheries and aquaculture sector in Ghana. Women are strongly associated with the post-harvest sector, e.g., processing, sales, distribution, and marketing; however, they also fish [4,5]. They obtain income, independence, and power through these activities. Income earned by women often has a stronger, more beneficial impact on household incomes [4]. Many studies indicate that millions of rural men and women engage in subsistence fishing on a seasonal or occasional basis, especially in inland fisheries in Asia and Africa, but are not recorded as "fishers" in official statistics due to engagement in other activities, which may be more economically productive, or a reluctance to self-report as fishers. Gender issues in the fisheries sector are seldom examined, and women’s important role is often not adequately considered [6,7].

Women’s participation in fisheries is often constrained by time (the result of household and reproductive responsibilities), education (literacy), access to capital, cultural rules, mobility due to household responsibilities, and discriminatory laws, among other barriers [8,9]. Fortunately, it has gained recognition despite a lack of quantitative data describing the scale of participation and contribution [7]. By failing to address gender-specific constraints on improving production and productivity, policies have often resulted in massive losses to the sector in terms of production and income, household food security and nutrition, particularly for the poor [6]. This study, therefore, examines women’s participation in West African Mangrove Oyster(Crassostrea tulipa)harvesting and its contribution to food security and nutrition in Ghana. The study will therefore add to knowledge of women in fishing and harvesting with a focus on oyster activities. The findings will contribute to the development of strategies for resource management and policy drive for the sector.

Women in Small-Scale Fisheries

Research on women and gender is not new in the study of fisheries. It has been around for at least four decades with the first studies conducted on women [10-12] and later gender. Over time, feminists, and gender researchers, as well as researchers from other disciplines, became interested in the gender niche and have provided significant contributions to the studies in this area [13-16]. A gender lens has had great influence in agriculture and agriculture research compared to fisheries research where the development and acceptance of gender topics and perspectives have taken a long time to materialize. Nowadays, gender research in fisheries and coastal communities covers themes like fisherwomen, women in fishing households and processing work, seaweed collectors, gatherers of other species like shellfish [17], and gender relations. Despite the significant participation of women in sea-related activities, researchers have not yet adequately reflected the interest and importance of this topic in Ghana.

Unfortunately, research on gender/women in fishery and aquaculture contexts is often hampered by limited data [14,18], predominantly because fisheries research has been slower than others to recognize the importance of gender within their purview. Few cultural and social researchers (example, ethnologists, anthropologists, and sociologists) were studying sexual or gender division of labour within fisheries, even though research on households and communities highlighted women’s presence in fisheries, as important workers for the fishing boat, in processing plants and the household [11,12]. In the fisheries sector, it is understood that men and women engaged in distinct and often complementary activities that are strongly influenced by the social, cultural, and economic contexts they live in. Male-female relations vary greatly and are based on economic status, power relations, and access to productive resources and services [6].

Fish catching in most regions is male dominated. Ocean-going boats for offshore and deep-sea fishing have male crews, while in coastal artisanal fishing communities' women often manage smaller boats and canoes. Women are mostly responsible for skilled and time-consuming onshore tasks, such as making and mending nets, processing, sales, and marketing catches, and providing services to the boats [5,6,19]. The roles of men and women in Africa fisheries are more complex than the general view that men fish at-sea and women market and process fish on land. Some women fish in smaller water bodies, at the edges of lagoons, and in estuaries, where they collect invertebrates, or oysters, crabs, and net small fish species or farm seaweed in intertidal zones [5,7].

Women’s work in fisheries, aquaculture, and shellfish harvesting is rarely found in statistics [14,20]. Their contribution to the economy of fishing households or enterprises is even less documented. Women’s fisheries are typically not included in government statistics, which means that they are not counted as fishers. Hence, even if it is an important fishery for food security, it is invisible in current statistics and fisheries management efforts. The value chain of these fisheries is often highly vertically integrated, with the same women harvesting, processing, and marketing the product [21]. This increases the opportunity for the empowerment of women in the management of these fisheries. The significance of women gleaner's activities for biodiversity conservation in coastal wetlands and the conservation of critical fish habitats linked to marine fisheries productivity is also generally overlooked. Women oyster harvesters in the Gambia and Ghana, who are economically marginalized and socially stigmatized, are evidence of this type of work and resource use [22].

In general, men in West Africa mainly control fisheries inputs (boats, engines, nets) and decisions about when, where, and how to fish. Women, on the other hand, mostly control and make decisions regarding post-harvest activities (where to sell, how to market, how to process, among others). Gleaning of shellfish in coastal wetlands is one exception that is often predominantly done by women who decide how to harvest, process, and market the product. The income generated through women’s production, transformation, and marketing of fish is vital for supporting the entire fishing industry [23]. Husbands and wives are economically dependent on each other, and a large portion of the return from fish sales is turned back into fisheries inputs such as fuel and fishing equipment. Women's income from fishing is also reinvested into the local economy and household and often, they withhold sales of fish for household consumption [7,24].

As much as 60% of seafood is marketed in Western Africa and Asia, by women, and in many parts of the world, they also do a significant number of shellfish gathering/clam gleaning. A fishery activity is often under-recognized, or not recognized at all [6]. Sectoral statistical systems fail to capture these broader contributions to livelihoods, nor do they consider women's engagement in fishery/shellfish harvesting activities. Also, women may not self-report/identify as being "fishers" even though they are engaged in these activities. In fisheries value chains, men and women have distinct roles, and their socio-economic status influences their power relations. Women constitute about half the population involved in fisheries development activities. In some developing regions, women have become important fish entrepreneurs who control a significant amount of money, finance a variety of fish-based enterprises, and generate substantial returns for households and communities [6].

In the inland fisheries of many countries, women are engaged in fishing and are taking a leading role in the rapid growth of aquaculture. They own and manage fishing boats and have their fishing gear [6]. Although comprehensive information is lacking, it appears that much of women’s catch is of small highly nutritious fish and other aquatic animals and is consumed at the household level [1]. In aquaculture, they often carry out most of the work of feeding, harvesting, and processing fish and shellfish. They become managers of small household enterprises, such as fishponds, and thus improve their families' income and nutrition [6].

Oyster Fishery in Ghana

The coastline of West Africa is distinguished by the presence of marginal estuaries of diverse origins and morphologies and are surrounded by large human population densities [25]. Estuaries are distinguished based on different criteria such as sediment composition, salinity, and mode of formation. Ghana has three kinds of estuaries based on salinity: a) Positive estuary: when seawater flows in as a bottom current with the lighter freshwater leaving as a surface current into the sea, b) negative estuary: when the evaporation rate exceeds the freshwater input thus resulting in hypersaline estuarine water which sinks and enters the sea as a bottom current, (the Whin Estuary is a typical example) c) Neutral estuary: when a balance occurs between evaporation and freshwater input, triggering from the top to the bottom a more or less uniform salinity profile. This sort of estuary is rare [26]. Estuaries have been the most valuable habitats in Ghana since they are closely related to mashes, mangrove swamps, salt marshes, and tidal flats. These wetlands are important features of the coastline of Ghana, which provides vital habitats for many fish and services for biodiversity that sustain the economy of the country. They are important sources of leisure, conservation, grounds for the nurseries of economic important marine birds and important fisheries including oysters [27-30].

The West African Mangrove Oyster (C. tulipa) is a tropical, euryhaline organism that thrives well at temperatures of 23 to 31 °C. It can be grown well in brackish swamps and sheltered in aquatic areas of 5 min depth and matures in approximately 7–9 months [31-34]. Oysters are most usually bound in this brackish system to the mangrove tree roots or, in the absence of such roots, to the rocky bottom substratum of the wetland. In Ghana, C. tulipa is most found in not less than 90% of southern coastal estuaries and lagoons [35]. Bivalves play an important role globally in the economy of many countries, be it in the form of highly developed industries or as a source of inexpensive protein to consumers. Quayle [36] revealed that shellfish from most tropical and subtropical nations, though they are exploited on a livelihood basis, especially the bivalves and crustaceans, they constitute a major source of much-needed protein for many rural communities. Some studies have been conducted in Ghana on freshwater oysters and other bivalves [37-41].

Women in the Oyster Fishery

The USAID Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (USAID/SFMP) supported oyster activities in Bortianor, Tetegu, Tsokome, and Faana communities along the Densu Delta in the Greater Accra region. This estuary of the Densu Delta is a microcosm of the degradation of Ghana’s marine environment. Located southwest of Accra, the growing human populations living in the Densu estuary have contributed to environmental degradation and dwindling fish and shellfish populations. Oysters are an overfished source of protein, the mangroves are overexploited, and the marine habitat is affected by global and local point and non-point sources of pollution. Like many artisanal shell fisheries in the global south, oyster harvesting in the Densu Delta is a vocation traditionally held by women, although some men also engage in this activity. The labour of women oyster pickers in this region has been invisible, underestimated, or not enumerated at all [13,42]. The USAID/SFMP project supported the Densu Oyster Pickers Association (DOPA) members to develop knowledge, confidence, leadership, and advocacy.

In the southern region of Benin, shellfish, particularly C. gasar are of great economic importance and provide sustainable financial resources for the grass-roots population through wild collections and traditional farming [43,44]. Like the pacific oyster (C. gigas), C. gasar is relatively inexpensive and easy to produce and does not require additional food to sustain its growth [45]. C. gasar provides sustainable revenues and is a good source of cheap protein for the people of the coastal towns and villages of the Benin coastal zone [46]. Oyster farming is widespread at the Benin (West Africa) coastal zone and provides sustainable revenues for grassroots [47]. C. gasar occurs in coastal lagoons, brackish water lakes, and in estuarine areas of depth between 0 and 40 m, preferred habitats are bottom substrates such as rocks, shells, debris, mud, and sands [48-50]. However, despite its economic and social importance in Benin, little is known about the ecology of this species which appears to be an important source of protein and revenues for the population inhabiting the Benin coastal area [51,52].

Oyster farming, an activity mainly performed by women in the region of Casamance, Senegal has been identified by the Senegalese Government and the World Bank as a key sector for sustainable development growth. Despite the hardships caused by lingering conflicts, determined female oyster farmers in Casamance have organized themselves to achieve financial independence and better fulfil the need of their families. In addition to supporting women-led oyster farms, the World Bank provided financial support for the restoration of Casamance's roads, the reviving of its rice industry, and the establishment of crucial peace and restoration programs. The oyster value chain has a huge potential for generating increased revenue for women in Casamance, especially with improvements in the production system allowing them to sell fresh oysters instead of smoked oysters, which are in high demand by hotels and restaurants in the region.

A pilot project was planned to experiment the cooperation between three oyster farms and disgorging facilities, to drain and clean fresh oysters before taking them to market, and thus boosting the entire value chain," explained by World Bank Senior Social Development Specialist Demba Balde, in charge of the Casamance Development Pole Project. The ceremony also included awarding of 100 knives, 48 pairs of boots, 50 pairs of gloves, 250 oyster lantern nets for oyster fattening, and two pirogues. All of which greatly improved the challenging and sometimes dangerous working conditions of these women and contribute to greater food security in the area. Female oyster farmers with additional equipment and financing mean that they can work in deeper waters, which enables a quicker growth of quality oysters for local consumption and export [53].

The Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP) Theory of Change for Gender Integration

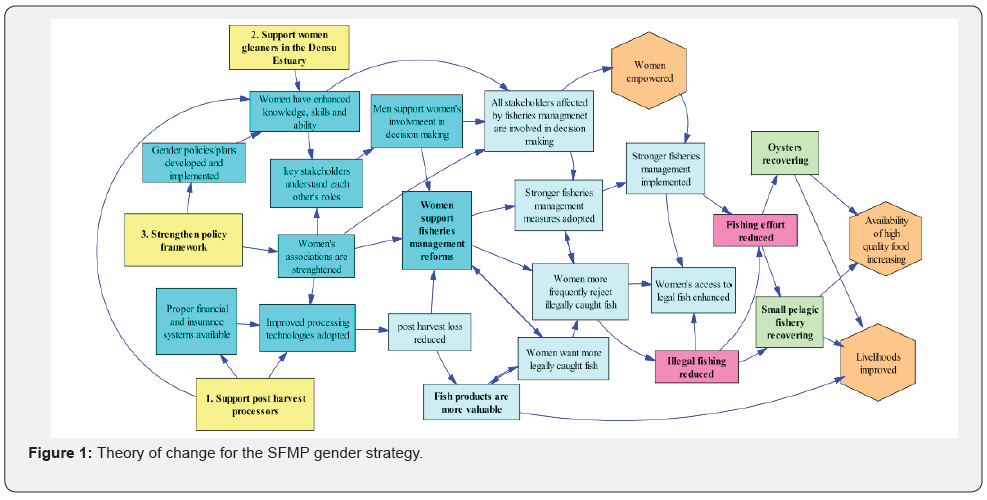

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP) implemented by the University of Rhode Island integrated gender and increase women’s voices in fisheries management in Ghana. One of these was to support Women Oyster Harvesters in the Densu Estuary. The SFMP developed a Theory of Change enabling women to be effective leaders advocating for fisheries management reform. It was built on the premise that engaging women in the fisheries sector is an important aspect of building powerful constituencies that demand a well-managed fisheries sector. It utilized three entry points such as gender mainstreaming, supporting women in the post-harvest sector, and women gleaners to effect change. Activities implemented triggered several positive and behaviour changes, among others. This can be broken down into several if-then statements:

i. IF men and women understand the importance of each other’s roles in the fisheries sector and men agree and support women’s involvement in decision making

ii. AND women are knowledgeable, capable, and equipped with the policy support, leadership skills, and resources to engage in fisheries management

iii. AND women harvesters and post-harvest processors have the capital and technologies necessary to make a living from available fish

iv. THEN women will support fisheries management reform and reject illegally caught fish,

v. which WILL THEN result in the implementation of stronger fisheries management

vi. And IN TURN reduce fishing effort and illegal fishing, which will provide ecosystem services that benefit human well-being and improve resilience

To realize its theory of change, SFMP supported gender-equitable participation in project activities and promoted gender integration and empowerment in the fisheries sector [54] (Figure 1).

Methodology

The Study Area

The Ga South Municipal was carved out from the Ga West District in November 2007 and was established by Legislative Instrument 2134 in July 2012 with Weija being the Municipal capital. It lies at the Southwestern part of Accra and shares boundaries with the Accra Metropolitan Area to the South-East, Ga Central to South-East, Akwapim South to the North-East, Ga West to the East, West Akim to the North, Awutu-Senya to the West, Awutu-Senya East to the South-East, Gomoa to the South-West and the Gulf of Guinea to the South. It occupies a total land area of about 341.838 km2 with about 95 settlements. The total number of households engaged in agricultural activities in the Ga South Municipality is 12.3%, which is considerably higher than the regional figure of 4.4% . More households are engaged in crop farming (76.5%), followed by livestock rearing (21.9%), tree planting (1.2%) with fish farming being the least (0.4%) [55].

The Densu Delta and wetlands lie in the river valley formed by the Aplaku-Tukuse and Weija-McCarthy Hills, west of Accra, Latitude 5° 31' N and Longitude 0° 20' W [56]. The main lagoons and delta are located to the south of the Winneba-Accra highway and bounded on the south by the Atlantic Ocean coastline between Bortianor and Gbegbeyise. The Aplaku-Bortianor road and the Lofa stream define the western and eastern boundaries, respectively. The Densu Delta covers some 34 km2 of wetlands made up of 21 km2 of the lagoon and freshwater marsh, 11 km2 of salt pans, 2.4 km2 of scrub, and coastal dune of 0.25 km2 [56]. The Densu Delta covers a total of 5,892.99 hectares. The oyster fishery in Ghana's Densu Delta is characterized by harvesting the West African mangrove oyster, previously known as Crassostrea gasar and recently known as Crassostrea tulipa, at various harvesting sites in the Delta. Tsokomey, Tetegu, Faana, and Bortianor are the major oyster landing and processing locations in the Ga South Municipal Assembly of the Greater Accra Region (Figure 2).

Sampling

A total of a hundred (100) women harvesters were sampled from Bortianor (30), Tetegu (30), Tsokome (30), and Faana (10) involved in oyster production/harvesting in the Ga South Municipality of Greater Accra region, Ghana. An equal number of respondents except in Faana was sampled from the communities. There were fewer women involved in oyster activities residing in the Faana community hence the sample size. The study employed multiple sampling methods to sample the target group. This was stratified sampling (4 communities), purposive sampling (women harvesters), and snowball sampling. The team was given a list of respondents in each community to work with but realized that (i) some members had left the women oyster pickers association for one reason or the other, (ii) had stopped harvesting (iii) had left the communities or iv) were not in town during the study. The team, therefore, sought the help of the focal persons of oyster harvesters in each of the communities in targeting women harvesters who are either members of the women oyster pickers association or not. The respondents interviewed, also assisted the enumerators by linking them to non-members of the association. An executive of the oyster pickers association also helped to coordinate the data collection.

Instrument

A semi-structured questionnaire was developed to solicit information from oyster harvesters in the study areas. This was uploaded onto a Kobo Toolbox placed on a tablet for data collection. The questionnaire was pretested and finalized for the data collection. The questionnaire is categorized into socio-economic data, consumers' preferences, sources of protein, and challenges faced in obtaining oysters.

Data collection and Analysis

Data was collected from four (4) communities (Bortianor, Tetegu, Tsokome, and Faana) along the Densu Delta in the Ga South Municipality in the Greater Accra region of Ghana. Data collected was extracted as an excel document from the kobo toolbox webpage, cleaned, and exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Analyzed data was presented descriptively in the form of frequencies, percentages, pie charts, minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation. Also, t-statistics was employed to examine the relationships of some responses. The benefit-cost analysis was also undertaken by employing an enterprise budget.

Results

Age of Respondents

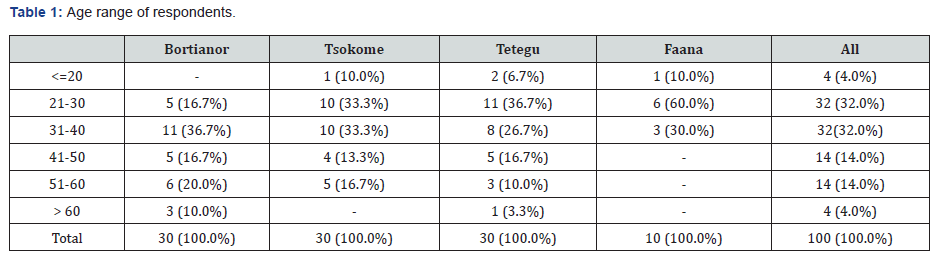

The ages of the harvesters interviewed ranged from 18 to 68 years with an average of about 40 years and modal age of 35 years (10%) followed by 42 years (8%). Also, the ages of respondents in Bortianor range between 22 to 64 years while those in Tsokome between 19 to 60 years. The average ages of the harvesters from these communities are 42 and 36 years, respectively. Further, the age range of the harvesters sampled in Tetegu fall between 18 to 68 years while those from Faana fall between 20 to 37 years. The mean ages of the women from the two communities are about 35 and 30 years, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the age range of the women harvesters by communities. In all, a good number of the interviewers (64.0%) sampled were between the ages of 21 to 40 years. The analysis by communities revealed that most of the respondents sampled from the Bortinanor community fall within the ages of 31 to 40 years (36.7%).

A good number of harvesters from Bortianor (70.0%) fall within the active labour force. Furthermore, an equal percentage of the harvesters sampled from Tsokome (33.3%) fall within the ages of 21 to 30 and 31 to 40 years. Results showed that 80% of the respondents in Tsokome are between the ages of 21 to 50 years. Additionally, the majority of the respondents interviewed in Tetegu are between the ages of 21 to 30 years (36.7%) followed by 26.7% who are within the ages of 31 to 40 years. The bulk of respondents sampled from Faana (60.0%) had their ages between 21 to 30 years. The active labour force is between 21 to 40 years. In all, the result showed that the active labour force (78%) was between the ages of 21 to 50 years.

Marital Status

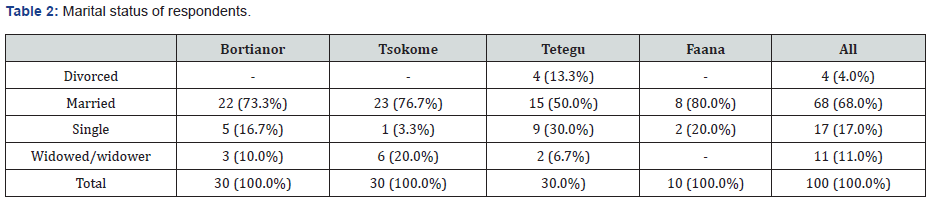

The marital status of the women oyster harvesters is exhibited in Table 2. Most of the respondents sampled from the communities are married (68.0%). Similarly, a higher percentage of the women sampled from each of the communities are married.

Religion

Results depict that, almost all the respondents sampled for this study are Christians making 98% of the total sample with only 2% being traditionalists.

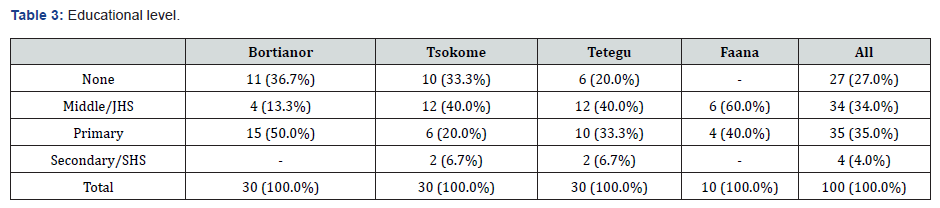

Educational Status

The educational attainment of the women harvesters is summarized in Table 3. The outcomes of the study showed that most of the women sampled over all had attained primary school level education (35.0%) followed by Middle school/ Junior High (34.0%). Quite a high percentage (27.0%) did not benefit from any formal education.Results revealed that a high percentage (69.0%) of the women involved in oyster harvesting in this study have completed the basic school level of education. Results further pointed out that, a high percentage (27%) of respondents from three out of the four communities had never benefited from formal education. Most of the harvesters from each of the selected communities were educated.

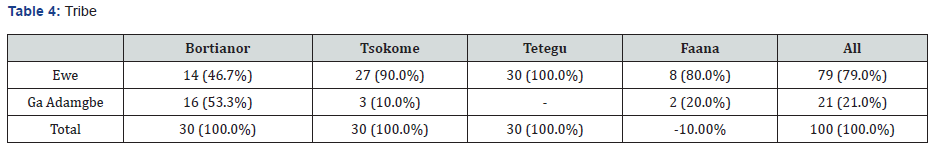

Ethnicity

Different tribes are involved in oyster harvesting activities in the Municipality. Results showed two tribes which are the Ewes and the Ga Adamgbes. The Ewes formed most women involved in oyster harvesting (79.0%). The Ewes (settlers) were in the majority at Tsokome, Tetegu, and Faana except in Bortionor. This implies that settlers are mainly into the oyster business in the study area (Table 4).

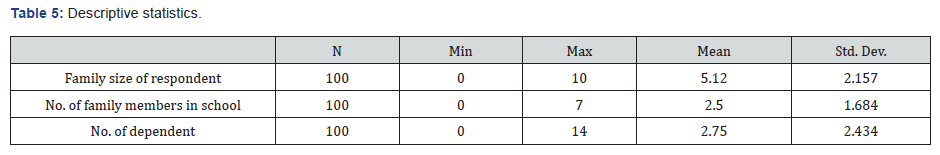

Family Size, Number of Children in School, and Dependency

Table 5 provides a summary of family size, number of family members in school, and the number of people depending on the respondents. The outcome of the analysis showed that family size ranges from 0 to 10 (5.1± 2.2).Also, the number of children attending school among respondents families ranged from 0 to 7 (2.5±1.684). Furthermore, the number of dependents of families falls between 0 to 14 people (2.7±2.4).

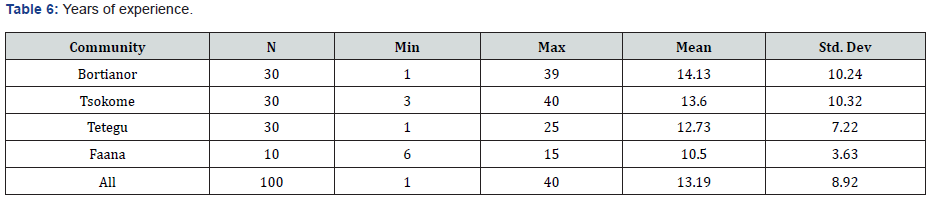

Experience

The experience of the women involved in oyster harvesting ranged from 1 to 40 years. The F-statistics show no significant relationship between the means of the years of experiences of respondents from the four (4) communities. Experience accrued by women in Bortianor in the harvesting of oysters ranged from 1 to 39 years whiles those from Tsokome ranged between 3 to 40 years. Additionally, those from Tetegu and Faana were between 1 to 25 years and 6 to 15 years, respectively (Table 6).

Oyster harvesting

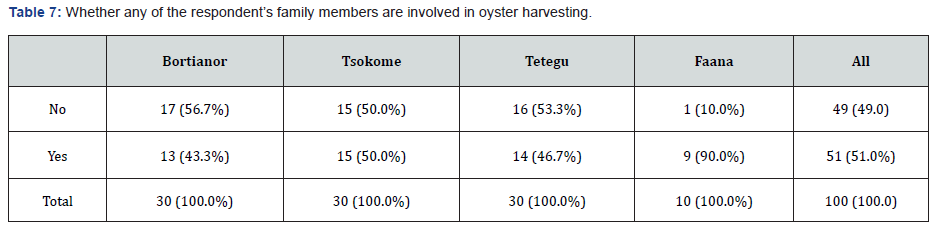

Overall, 51% of the total respondents had at least a family member involved in oyster harvesting while 49% undertook the activities alone (Table 7). The families were involved in either harvesting, processing, and/or trading.

Sources of Income

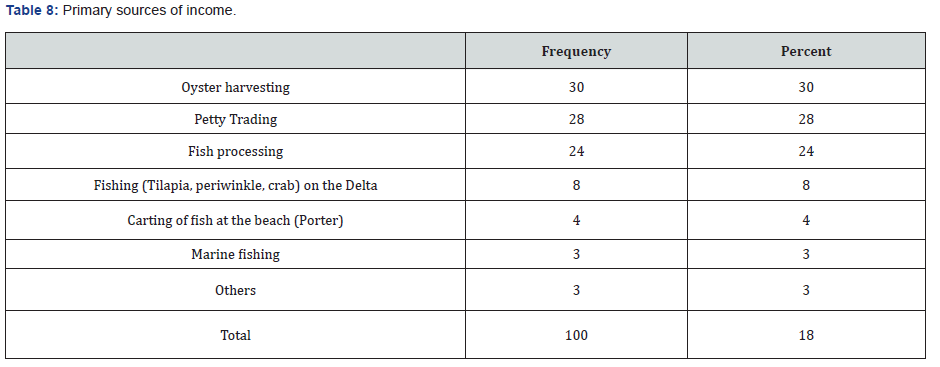

i. Primary source of income of oyster harvesters

Table 8 depicts primary source of income of the oyster harvesters. The three (3) major sources are: oyster harvesting (30%), petty trading (28%) and fish processing (24%). Results showed that 70% of the harvesters were involved in other sources of income apart from oyster harvesting. It implies that oyster activities were not their major source of employment.

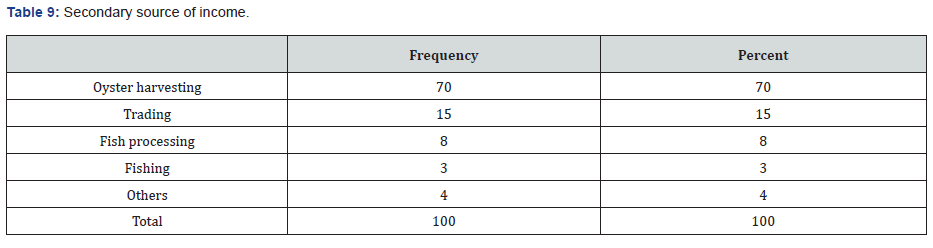

ii. Secondary source of income of oyster harvesters

Furthermore, the results revealed that majority of the respondents operated oyster activities as a secondary source of income. (Table 9)

Share of Income Made from Oyster out of the Total Household Income

The proportion of income made from oyster harvesting out of the total household income for the 7 months harvesting period ranged from 2 to 100% (45%±28%). The modal share of income generated from oyster harvesting is 20 percent (representing 22%) followed by 60 percent (representing 10%). Overall, a few (about 7%) of the total respondents made 100% of total household income from oyster activities. They can be found in three (3) of the four (4) communities selected.

The proportion of income made from oyster harvesting out of the total household income for the various communities is displayed in Table 10. The share of income made from the oyster business for women in Bortianor ranged from 2 to 100% (33.65±27.76%) while Tsokome was between 5 to 100% (41.88% ± 26.45%). Those from Tetegu made 20 to 100% (57.08±26.12%) while those from Faana was between 20 to 80% (51±28.75%). T-test analysis showed a 1% level of significance between the mean income made by oyster harvesters from the communities out of their total household income.

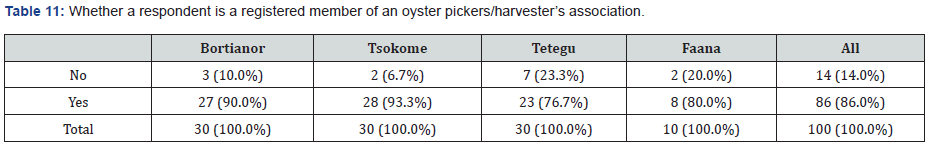

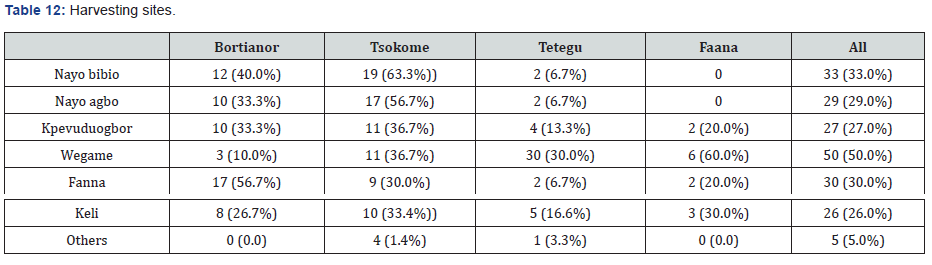

Respondents were asked if they were registered members of an oyster pickers association. Out of the total harvesters sampled, most (86%) responded affirmatively. The outcome of this study suggested a higher percentage of the respondents from the communities were members of the oyster harvesters’ association (Table 11). The respondents harvested oysters from various locations (Table 12). This included Nayo bibio, Nayo agbo, kpevuduogbor, Wegame, and Faana. In all, half of the women (50%) in oyster harvesting gathered oysters from Wegame (50%) followed by Nayo bibio (33.0%) and Faana (30.0%).

The respondents harvested oysters from various locations (Table 11). This included Nayo bibio, Nayo agbo, kpevuduogbor, Wegame, and Faana. In all, half of the women (50%) in oyster harvesting gathered oysters from Wegame (50%) followed by Nayo bibio (33.0%) and Faana (30.0%).

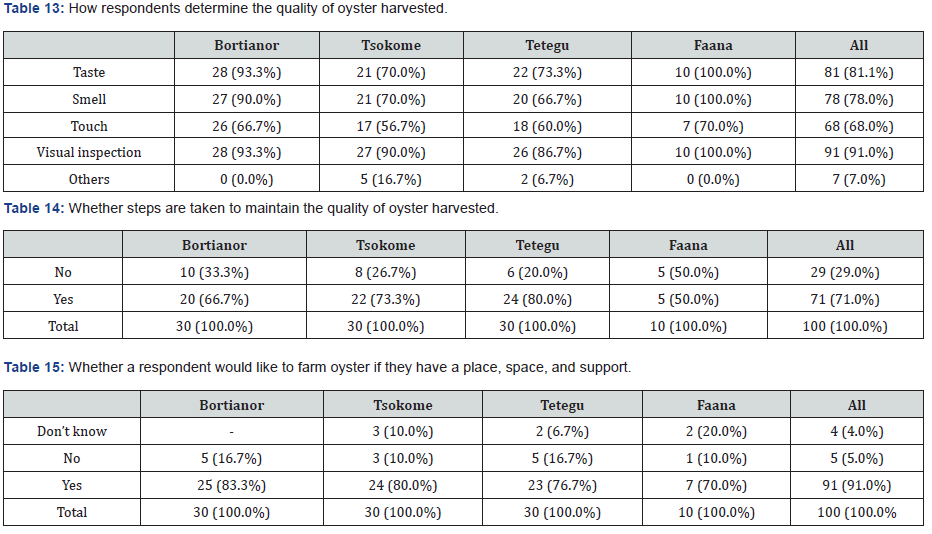

The respondents can determine the quality of oyster harvested by employing the following quality characteristic: taste, smell, touch, and visual inspection (Table 13). All the women from the selected communities examined the quality of oysters by employing such traits. Visual inspection was the main trait (91%) for the determination of quality followed by taste (81.1%). Table 14 shows the percentage of the respondents who maintained the quality of harvested oysters. In all, about three-quarters of the respondents (71.0%) responded positively to maintaining the quality of oysters harvested.

The harvesters employed various steps such as icing, packaging, rapid transfer to the market, and processing to maintain the quality of harvested oysters to minimize post -harvest losses. Table 15 shows the outcomes of the willingness of respondents to farm oysters if they had a place, space, and support. In all, a good number of them (91.0%) said they would take part in oyster farming. Results suggested that in all the communities, a high number of harvesters were willing to farm oysters when the opportunity becomes available.

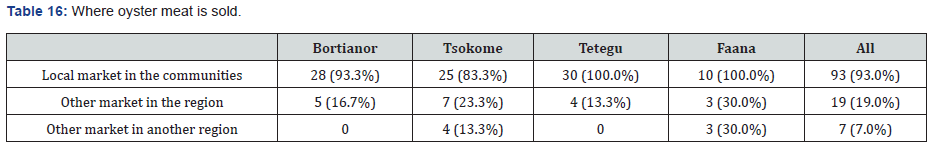

Mode of Oyster Harvesting

It was also realized from the analysis that, all the respondents sampled from the (4) communities gathered oysters by hand. The respondents interviewed revealed that they sold their oyster meat at the local market (primary market), other markets in the region, and other markets in other regions (Table 16). In all, most respondents (93%) sold their oyster meat at the local market in the selected communities. Very few also sold the meat in markets outside the region. It is evident that a higher percentage of the respondents from each of the communities did not go far outside the region to sell oyster meat. Oyster meat according to the respondents from the sampled communities is sold in many forms such as steamed/boiled, dried, fried, and in brine water (Table 17).

The most occurring form is the steamed/boiled. This is because, most women steamed the live oyster with the shell before opening it for the removal of the meat while a few remove the fresh meat from the shell. It was also realized from the outcome that very few respondents (9%) apply two types of methods of processing oyster meat (steaming/boiling and drying). Thirty (30%) of the respondents sold oyster shells, while the majority (70%) did not (Table 18). A higher percentage of the respondents from Bortionor, Tetegu, and Faana did not sell the oyster shell. According to them, the shells are thrown away or left around the house and given to whoever asked for it. Those who sold the shells gave them to companies, individuals in the community, and some individuals outside the community. According to such respondents, the shells are used for any of the following:

a) Mother shell to catch spat,

b) Ballaster for roads,

c) Poultry grit, and

d) Lime flour (animal feed)

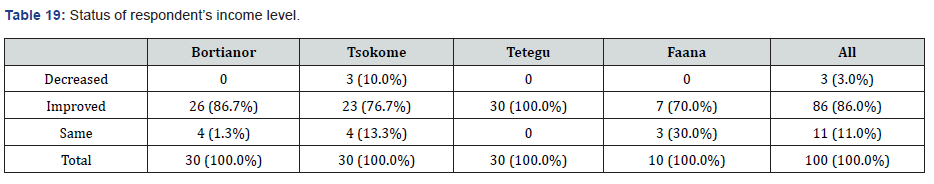

Income level

The respondents were again asked to state the status of their income level due to their oyster activities. Results showed that their income level during the study had improved (86%) because of the oyster business. A few had their income remaining the same. The decrease in income may be due to decline in oyster activities or that they did not pursue the oyster activities as a business (Table 19).

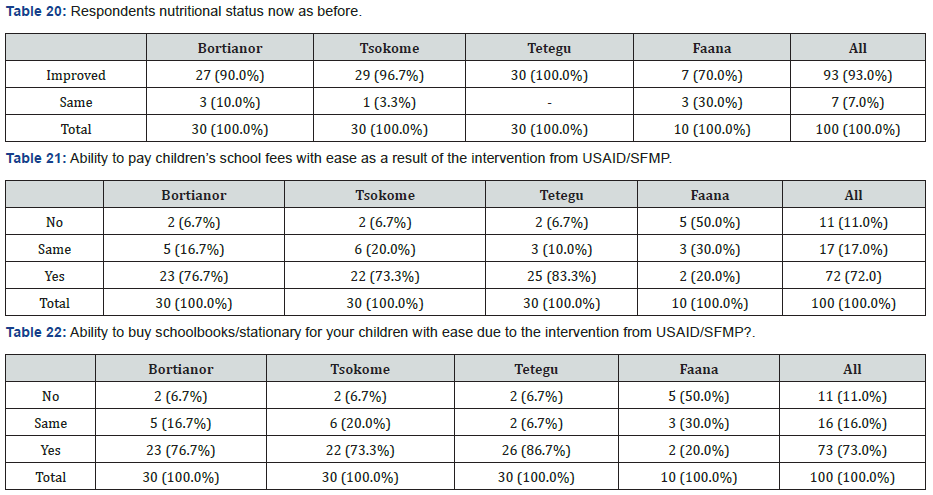

Nutrition

Furthermore, when they were asked if their nutritional level had improved, 93% overall responded affirmatively with 7% saying otherwise (Table 19). There were equally very high percentages of the respondents from the communities who indicated that their nutritional level had improved because of their involvement in oyster activities. The researchers observed that the sampled communities depended mostly on the consumption of oyster meat during the harvesting season.

Livelihood

The impact of the intervention from United State Agency for International Development (USAID)/Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP) on the respondents is summarized in Tables 20. The outcomes of the findings showed that 72% of the sampled respondents were able to pay their children’s fees with ease due to income accrued as a result of the intervention (Table 21). The parents pay the fees of children in the private school and provide money for their transportation. Parents whose wards attend public schools were also able provide transportation for their wards. This used to be a difficult in the past. Some women are still faced with the challenge of fee-paying while others have not seen any change in the payment of their wards’ school fees. Also, there was a very high percent of the women who were able to buy schoolbooks/stationary for their children with ease due to the intervention from USAID/SFMP. Results point to the fact that 73% can buy stationary including books with ease while 16% faced the same problem as before (Table 22).

Assets Procured

The respondents were asked to list items and structures procured due to income generated from the sale of oysters. These included clothing, footwear, cooking utensils and basins, schoolbooks, earrings, phones, serving trays. A respondent reported of putting up a building from the income obtained from oyster activities.

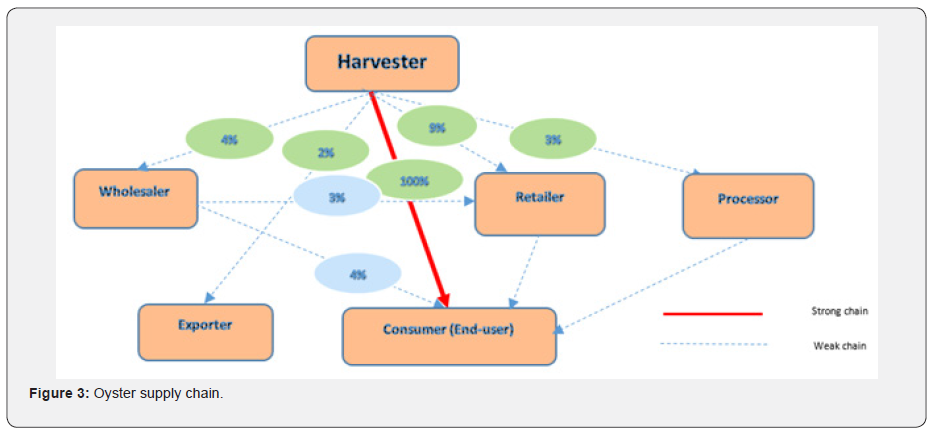

Oyster Supply Chain in Ghana

According to the women who are members of the Oyster Harvesters Association, Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP) under USAID provided the following supports to the harvesters: baskets, knives, snickers, life jackets, and gloves to enhance oyster harvesting. Figure 3 summarizes the supply chain of oyster harvesting in the Ga South Municipality. The main supply chain is where all (100%) the women performed the role of harvesters, processors, and traders at the same time. They sell the oyster meat directly to the consumer (End-user).

The consumers were mainly households. Other consumers include local restaurants (chop bar), restaurant.

Very few of them sold their product directly to wholesalers (4%), retailers (9%), processors (3%), and exporters (2%). The oyster supply chain is simple in structure. According to those who sold the meat to exporters, this is done through mostly agents who came to buy on behalf of the exporter hence did not know the destination countries. They indicated that oyster was sold to the foreigners on a few occasions, and this was on demand.

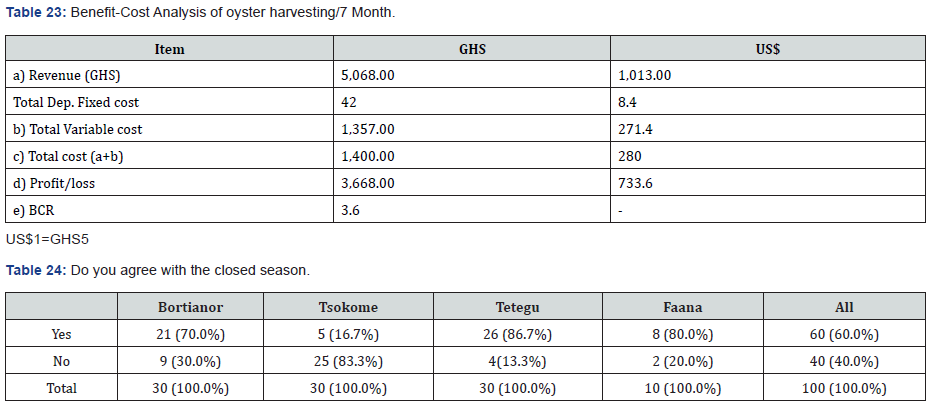

Benefit-Cost Analysis of Oyster Harvesting

Average total revenue accrued from the harvesting and sale of oyster amounted to GHS5,068.00 (US$1,013). The total depreciated cost and variable cost were GHS1,357.00 (US$271.40) and GHS1,400.00 (US$280.00) respectively. Results showed that the respondents made a profit of GHS3,668.00 (US$733.60) for 7 months (the period of harvesting); GHSS524.00 (US$104.80) for a month and GHS131.00 (US$26.20) for a week. The benefit-cost ratio showed that the respondents gain GHS3.00 to a GHS1.00 investments (Table 23). Revenue increased by three-fold as a result of a unit cost of investment. It implies that oyster harvesting is profitable. (The analysis excluded profit made from the sale of oyster shells).

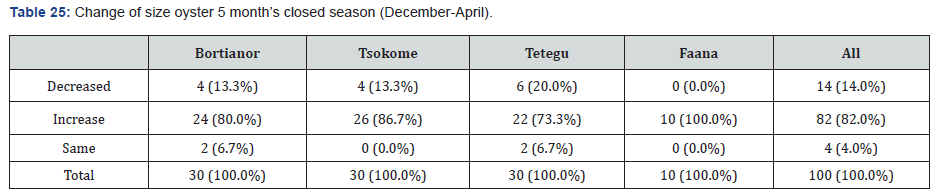

Closed Season of the Delta

In co-management of resources, users and managers share responsibilities in managing the resource. The study gathered some information on the co-management `practices in the selected communities. The communities and the associations’ collaborated with the United State Agency for International Development (USAID)/Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP) to institute a 5 months (December to April) closure of the water body (Densu Delta). The respondents were asked if they agreed with the closed season of the Densu Delta. The findings showed that 60% of them answered affirmatively while 40% did not. Table 24 revealed a higher percentage of respondents who agreed with the closed season of the water resource among the selected communities. Furthermore, out of the 60 respondents who agreed with the closure, a little above half (55%) were of the view that the seven months should be maintained while 40% called for an increase. Very few (5%) did not respond to the question.

Activities respondents were involved in during the closed season of the Densu Delta

The harvesters were involved in the following activities during the five months closed season (December - April) of the oyster fishery:

i. Petty trading (36%)

ii. Marine fish processing (23%)

iii. Fishing in marine waters (10%)

iv. Porter (carting marine fish to shore or homes of buyers) (2%)

v. Rendering washing services (1%)

vi. Schooling (4%)

vii. Fuel harvesting (2%)

viii. Hairdressing (2%)

ix. Nothing (13%)

x. No response (7%)

Size of Oyster Harvested

The respondents were asked to state whether the size of oysters harvested after the closed seasons increased, decreased, or remained the same. Most respondents (82.0%) indicated that the sizes increased (Table 25). This response did not take into consideration how heavy (weight) or the dimensions (size) of the oysters. Also, 14% of the respondents said the sizes decreased. Most respondents in each of the communities reported of increase in size of the oysters after the closed season.

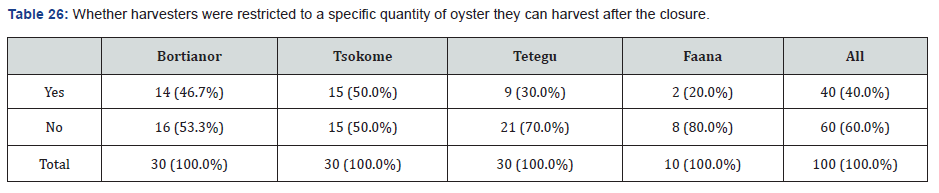

Restrictions to Quantity of Oysters Harvested as a Management Tool

The respondents were asked if they were restricted to a specified quantity of oysters when they went for oyster hunting. The results revealed that most of the interviewees (60%) said that even though they were not restricted to the quantity of oysters harvested, they were advised to harvest what they could manage without disposing off what is not needed. Forty percent (40%) indicated that, they were restricted to quantities harvested (Table 26).

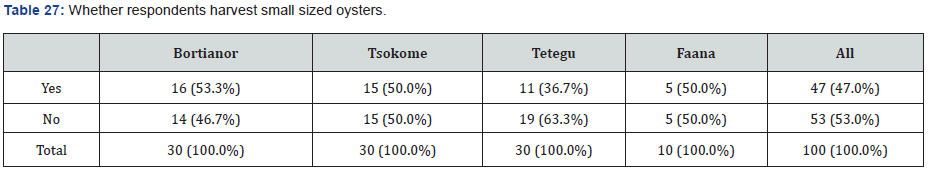

Harvesting of Small Sized Oysters

Managing the resources is of interest in fisheries management among the sampled communities. The study inquired if harvesters picked small size oysters. The results showed that in all, a little above half of the respondents (53%) did not harvest small sized oysters as against 47% who did (Table 27). There were high percentages of the harvesters from the selected communities who gathered small sized oysters.

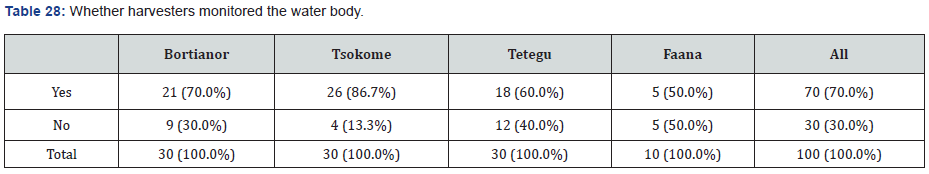

Policing of Water Body

When the respondents were asked if they helped in policing the water body as a co-management strategy, to prevent people from poaching oysters during the closed season, most answered affirmatively (70%) (Table 28). Quite a high percentage of harvesters from the communities except Faana patrolled the water body against the poaching of oysters.

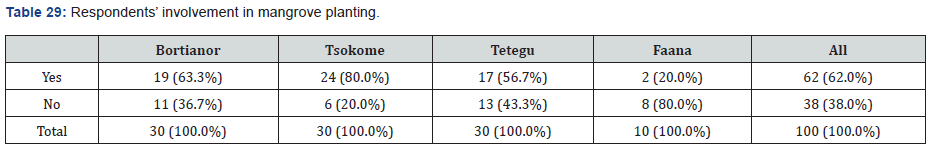

Planting of Mangrove

Mangrove is believed to protect the coastal shorelines against storms, flooding, maintain water quality, and filter pollutants, among others. Respondents were asked if they were involved in the planting of mangroves at the estuaries of the Densu Delta. Most interviewee (62%) from this study were involved in mangrove planting as against 38% who were not (Table 29). In all, a high percentage in all the communities were not involved in mangrove planting.

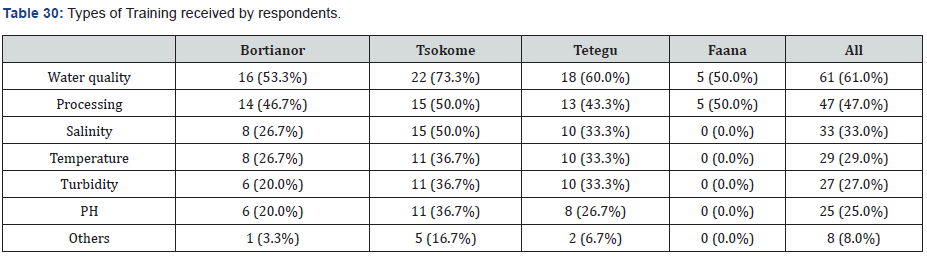

Training

Some respondents (members of Oyster Harvesters Association) had benefited from various training programs (Table 29). These included training on temperature, water quality, turbidity, salinity, PH, and processing. The three major trainings were in areas of water quality (61.0%), processing (47.0%), and salinity (33.0%). Other trainings included breeding and hygienic packaging. Results further pointed out that 20% of the sampled respondents benefited from 5 training programs made up of water quality, temperature, turbidity, salinity, PH, and processing.The respondents attested to the fact that, they faced various challenges in the oyster activities. These were:

i. Lack/inadequate protective working gear,

ii. Lack/inadequate harvesting items/tools (shoes, snickers, knives, etc.),

iii. High hiring cost of boat/canoes to aid in harvesting and in deeper waters,

iv. Injures from cuts on bodies (sole, feet, fingers) during harvesting,

v. Laborious and time-consuming work (picking, packing, unpacking, and processing),

vi. Excess heavy smokes because of steaming,

vii. High cost of fuel for steaming,

viii. Burns from heat (fuel and hot water) in the course of steaming,

ix. Difficulty in removing fresh oyster meat from shell,

x. High post-harvest loss,

xi. Limited oyster markets,

xii. Low selling (market) price,

xiii. Lack/inadequate proper tools for processing,

xiv. Financial challenges,

xv. Flooding of the estuaries by the opening of the dam,

xvi. Diving at deeper waters at some harvesting locations,

xvii. Lack/inadequate labour, and

xviii. Walking long distances to some locations to harvest oysters

Discussion

The findings of this study provide some information and data on women in West African Mangrove oyster (Crassostrea tulipa) harvesting and contribution to food security and nutrition in Ghana. Assessment of this topic is very relevant for management strategies of oyster harvesting in Ghana. Oyster activities are undertaken in the selected communities in the Ga South Municipality for mainly food and income. The age range of the women harvesters sampled is between 18 to 68 with an average of 40 years. The results showed the elderly and youth in oyster harvesting. According to [57,58], in other parts of the world, particularly in Japan and the USA, the oyster sector comprised both elderly and the youth. Hess et al. [58] concluded from their study that, women form 62% of oyster fisher folks in Bayou, Le Batre, Louisiana, and Southeast Asia where oyster activities are carried out. Also, Janha, Ashcroft, and Mensah, [59] indicated that women in Gambia, Senegal, and Benin are also reported to be involved in oyster harvesting. A trip by women oyster harvesters from Ghana visited Gambia to witness how oyster harvesting is done.

A good number of the interviewees fall within the age of 21 to 40 years (64%), are married (68%), and have completed a basic level of education (69%). There was an equally high percentage of the harvesters who were not formally educated (27%). This could affect their ability to read and write, understand, and adopt technology in areas of oyster harvesting as compared to their educated counterpart. All the communities reported a high percentage of women attending a basic level of formal education. Also, of the four communities, Bortianor reported the highest percentage of respondents uneducated (36.7%). In all, a good number (73%) of the women were formally educated. Most of the harvesters were Christians (98.1%) and are of the Ewe tribe (78.8%) who are settlers in the selected communities. This implies that the natives are not very much involved in the oyster harvesting activities. The family size of the sampled respondents ranged from 0 to 10 with an average of 5 while the number of children in school also ranged from 0 to 7 with a mean of about 3.

Additionally, the number of dependents ranged between 0 to 14 people with an average of 3 people. The experience of oyster harvesters ranged from 1 year to 40 years with an average of 13 years. This showed that harvesters had acquired much experience in oyster picking. In all, about half of the respondents indicated that their family members have been involved in oyster activities. Oyster provides sustainable revenues and a good source of cheap protein for the people of the coastal towns. According to Pascoe et al., [60] and Tzanatos [61], socio-economic characteristics affect a wide range of behaviours in a wide range of industries including fisheries and aquaculture. This can shape the development of the industry as well as its response to external drivers, including environmental, economic, and policy drivers. Consequently, investigating the socio-economic profile of fishers and aquaculturists can potentially provide important insight into the industry structures and issues, and thus may offer a base for modifications to the industry management.

The three major primary sources of income of the women are oyster picking/harvesting, petty trading, and fish processing. Oyster picking/harvesting ranked the first major secondary source of income followed by trading and fish processing. The outcome of the study showed that oyster picking is not a major source of income for the women. The proportion of income made from oyster harvesting out of the total household income ranged from 2% to 100%. The household of a few respondents depended solely on the oyster activities while others had either other sources of income or that some members of the households such as spouse provide financial support. According to Janha, Ashcroft and Mensah [62], women are mostly engaged in low value-added activities such as fish cleaning and carrying of loads of fish on their head (porters) from the landing sites. The average household income is reported to be about GHS3,668.00 (US$733.60) for the period of harvesting (7 months).

The average income reported from this study was 45% out of the total household income. According to Britwum [23], the income generated through women’s production, transformation, and marketing of fish is vital for supporting the entire fishing industry. Harper, et al., [7] and Weeratunge, Snyder, and Sze, [24] were also of the view that women's income from fishing is also reinvested into the local economy and household, and often, they withhold sales of fish for household consumption. A little more than half of the respondents (51%) indicated that their family members (spouse, sisters, mothers, aunties, children, etc.) are involved in oyster harvesting. Most of the women interviewed (86%) were members of the oyster pickers association. The harvesting sites included Nayo bibio, Nayo agbo, Kpevuduogbor, Wegame, Faana and Keeli. Most respondents pick oysters from Wegame. Janha, Ashcroft, & Mensah, [59] identified five (5) oyster collection sites. These were Nayo (Bibio and Agbo), Kpevoduvo, Kele, Hoga Nukaji, and the Bortionor/Tsokomey Estuary.

The attributes employed by the respondents to assess the quality of oysters included taste, smell, touch, and visual inspection. Oyster is mostly processed quickly to maintain the quality after harvesting and avoid high post-harvest loss. The maximum number of the harvesters (91.4%) interviewed had shown interest in oyster farming when given the necessary support. All the women interviewed harvest the oyster by hand (picking). Oyster meat is mostly sold at the local markets (93%) in the sampled communities to individuals for household consumption, in the boiled/steamed, dried, smoked, fried, in brine water, and fresh form. All the respondents sold oyster meat in the boiled/steamed form (100.0%) while 30% of them also sold the shells to companies and individuals to be used as ballaster for road, poultry grit, and lime flour as animal feed, among others. According to Ampofo-Yeboah [63], empty shells are used as a source of calcium in poultry feed and lime manufacturing. Atindana et al. [40] suggested that respondents involved in oyster harvesting at Whin estuary add value to oyster meat by adding spices, frying, smoking, and packaging for sale.

Results from the study revealed that oyster shells can be used to catch spat, this is sometimes put back into the Densu River (Estuary). The study revealed that 86% of the women attest to the fact that their income level had improved because of oyster activities. The study discovered that, most women can pay their children's school fees and buy schoolbooks/stationery with ease because of the intervention from Sustainable Fisheries Management Project/USAID. Some of the assets procured from the income made from oysters included clothing, footwear, cooking utensils and basins, schoolbooks, earrings, phones, serving trays. A respondent invested her income in putting up a residential facility. Oyster harvesting is a profitable venture with a vertically integrated simple supply chain structure. This finding is confirmed by Njie and Drammeh [21]. The same women undertook most of the activities such as harvesting, processing, and trading/marketing the oyster product.

Some harvesters who are members of the oyster pickers association benefited from training in ecology, biology and quality data parameters, mangrove restoration through replanting, and nursery management to improve oyster habitat. The study indicated that, a good number of the respondents were in favour of the closure of the water body (80%) for 5 months (December to April) as a management strategy. Janha, Ashcroft, and Mensah, (2017) indicated that fisherfolk did not observe any official closed season in the past. They specified that the fisherfolk in the past however cease all activities on the river and its estuary during six weeks (between August and October) in observance of a festival customary rites (Homowo), before the annual festival (during the first to weeks of September) and then after the festival (four weeks from mid-September to Mid October).

During the months closure, the harvesters (women) were involved in various activities including marine fish processing, carrying load (porters), petty trading, and fishing on the sea, among others. Most respondents suggested that the closure led to the increase in the size of oysters (82%). They were advised to harvest the quantity of oyster they could process avoiding wastage. Results pointed out that quite a significant percentage of the women (47%) harvested small size oysters even though most did not (53%). Most (70%) helped in conducting monitoring along the delta to prevent poaching and help plant mangrove (62%) as a co-management policy. These activities agree with SFMP developed theory of Change enabling women to be involved in co-management programs [54]. Trainings were carried out for most harvesters in water quality, processing, temperature, PH, salinity, and turbidity, among others.

Some of the challenges listed by the oyster harvesters included lack/inadequate protective working gear, Lack/inadequate harvesting items/tools (shoes, snickers, knives, etc.), high hiring cost of boat/canoes to aid in harvesting in deeper waters, injuries from cuts on bodies (sole, feet, fingers) during harvesting, laborious and time-consuming work (picking, packing, unpacking, and processing), excess heavy smoke during steaming, high cost of fuel for steaming, and high post-harvest loss among others. Janha, Ashcroft, & Mensah [59] in a study identified inadequate protective working gear, lack of personal boat for harvesting, and inadequate diving skills which limits access to deep water areas where oysters abound, intrusion of freshwater from the Weija Dam led to the death of oysters.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Women are very much involved in oyster harvesting. Oyster harvesting is a profitable venture with minimal expenditure, contributes to improved family income, food security, and nutrition among the sampled coastal communities. It is recommended that the government through the regulator (Ministry of Fisheries and Fisheries Commission), District and Municipal Assemblies develop policies, programs, and projects to support the sector. Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) should also complement government’s contribution to this fishery. It is again recommended that women should be supported and encouraged to farm oyster to improve their income and household nutrition. The value chain should be improved to contribute to employment. More awareness creation should be promoted about the nutritional quality of oysters and the kinds of dishes it can be used to prepare.

References

- FAO (2018) State of world fisheries and aquaculture: Meeting the sustainable development goals.

- Hayes D, Lauden R (2009) Food and nutriion Marshall Cavendish.

- FC (2020) 2019 Fisheries Commission annual performance report. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, Fisheries Commission, Accra.

- Porter M (2012) Why the coast matters for women: a feminist approach to research on fishing communities. Asian Fisheries Science 25S: 59-73.

- Agbekpornu H, Yeboah D, Quaatey S, Pappoe A, Ennin JE (2016) Value Chain Analysis of Captured Shrimp and Tilapia from Keta Lagoon in Ghana. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology 14(1): 1-11.

- FAO (2016) Promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment in fisheries and aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organiation of the United Nations Organiations. Rome.

- Harper S, Zeller D, Hauer M, Pauly D, Sumaila R U (2013) Women and fisheries: Contribution to food security and local economies. Marine Plolicy 39: 56-63.

- FAO (2015) Voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries in the context of food security and poverty eradication.

- McNally C B, Crawford B, Nyari-Hardi B, Torell E (2018) MSMEs/VSLAs formative evaluation report. The USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). GH2014_ACT153_CRC, Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett, RI.

- Gerald S (1986) BKvinners makt og avmakt - et kjønnsrolleperspektiv på forvaltning av faglige interesser (Women’s power and powerlessnes - a gender perspective on managing work interests). FDH-Report, Alta: Finnmark University College.

- Gerrard S (1975) Arbeidsliv og Lokalsamfunn: Samarbeid Og Skille Mellom Yrkesgrupper i et nord-norsk Ffskevær (Working life and local community - collaboration and divisions among workers in a North-Norwegian fishing village). Magistergrad thesis, Tromsø: Institutt for Samfunnsvitenskap, Universitetet i Tromsø.

- Porter M (1991) Time, the life courses and work in women’s lives: reflections from Newfoundland. Women's Studies International Forum 14(1): 1-13.

- Bennett E (2005) Gender, fisheries and development. Marine Policy 29(5): 451-459.

- Kleiber DM, Leila HM, Vicent AC (2014) Gender and small-scale fisheries: a case for counting women and beyond. Fish and Fisheries 16: 547-562.

- Zhao M, Tyzack M, Anderson R, Onoakpovike E (2013) Women as visible and invisible workers in fisheries: a case study of northern England. Marine Policy 37: 69-

- Woke G N, Wokoma A I (2000) Effect of organic waste pollution on the Macrozoobenthic organisms of the Elechi Creek, Port Harcout. African Journal of Applied Zoology and Environmental Biology 1(3): 197-200.

- Gopal N, Williams M J, Gerrard S, Siar S, Kusakabe K, et al. (2017) Women in aquaculture and fisheries: engendering security in aquaculture and fisheries. Papers from the 6th Global Symposium in Gender in Aquaculture and Fisheries. 3–7 August 2016, 11th Asian Fisheries and Aquaculture forum. Bangkok, Thailand.

- Harper S, Salomon A K, Newell D, Waterfall P H, Brown K, et al. (2018) Indigenous women respond to fisheries conflict and catalyze change in fisheries governance on Canada’s Pacific coast. MAST Thematic Collection (En)Gendering change in Small-Scale Fisheries and fishing communities in a Globalized World.

- Yankson K, Kendall M (2001) A student’s guide to the Fauna of seashores in est Africa. Darwin Initiative, Newcastle, England.

- Santos A (2015) Fisheries as a way of life: gendered livelihoods, identities and perspectives of artisanal fisheries in eastern Brazil. Marine Policy 62: 279-288.

- Njie M, Drammeh O (2011) Value chain of the artisanal oyster harvesting fishery of the Gambia. Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island. Narragansett, Rhode Island.

- Lau J, Scales I (2016) Identity, subjectivity and natural resource use: How ethnicity, gender and class intersect to influence mangrove oyster harvesting in The Gambia. Geoforum 69: 136-146.

- Britwum A O (2009) The gendered dynamics of production relations in Ghanaian coastal fishing. African Gender Institute, 1(12): 69-85.

- WHO (2010) In Safe management of shellfish and harvest waters. In: G Rees, K Pond, D Kay, J Bartram, J Santo (Eds.) IWA, London.

- Amadi AA (1990) Comparative ecology of estuaries in Nigeria. Hydrobiologia 208: 27-38.

- Yankson K, Obodai E A (1999) An update on the number, types and distribution of coastal lagoons in Ghana. Journal of Ghana Science Association 2: 26-31.

- Blaber S J (2008) Tropical estuarine fishes: Ecology, exploitation and conservation. Blackwell Science Limited.

- Dahanayayaka DG, Aratne MJ (2006) Diversity of Macrozoobenthic community in the Negombo estuaries, Sri Lanka with special reference to environmental conditions. Sri Lanka Journal of Aquatic Sciences 11: 43-61.

- Plavan AA, Passadore C, Gimenez L (2011) Fish assemblage in a temperature estuary on the Uruguay coast: Seasonal variation and environmental influence. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography 58(4): 299-314.

- World Bank (2012) Hidden harvest: The global contribution of capture fisheries. Economic and sector work. Washinting DC.

- Ansa E J, Bashir R M (2007) Fishery and culture potentials of the mangrove oyster (Crasosstrea gasar) in Nigeria. Research Journal of Biological Sciences 2: 392-394.

- Kamara AB (1982) Preliminary studies to culture mangrove oysters, Crassostrea tulipa, in Sierra Leone. Aquaculture 27(3): 285-294.

- Obodai AA (1999) The present status and potential of the oyster industry in Ghana. Journal of Ghana Science Association, 2(2): 66-73.

- Yodanis CL (2002) Constructing gender and occupational segregation: a study of women and work in fishing communities. Qualitative Sociology 23: 267-290.

- Sultan AE, Yankson K, Wubah DA (2012) The effect of salinity on particle filtration rates of the West African mangrove oyster. Journal for Young Investigators 24(4): 55-59.

- Quayle D B (1989) Troical Oysters: Culture and Methods. Otawa: International Development Research Centre TS17e.

- Adjei-Boateng D, Wilson JG (2013) Body condition and gametogenic cycle of Galatea paradoxa (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in the Volta River estuary, Ghana. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 132: 94-98.

- Adjei-Boateng D, Obirikorang KA, Amisah S (2010) Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the tissue of the clam Galatea paradoxa and sediments from the Volta estuary, International Journal of Environmental Research 4(3): 533-540.

- Amoah P, Keraita B, Drechsel P, Abaidoo R, Konradsen F, et al. (1990) Low cost options for health risk reduction where crops are irrigated with polluted water in West Africa. IWMI research Report No. 141, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- Atindana SA, Fagbola O, Ajani E, Alhassan EH, Ampofo-Yeboah A (2020) Coping with climate variability and non-climate stressors in the West African Oyster (Crassostrea tulipa) fishery in coastal Ghana. Maritime Studies 19: 81-92.

- The World Bank (2014) The Pearls of Casamance: Women-Led Oyster Farms Foster Sustainable Development in Senegal.

- Ogden IE (2017) The uncounted dimension in fisheries management: Shedding light on the invisible gender. BioScience 67(2): 111-117.

- Adite A, Kinkpe RK, Sossa GN, Viah CC (2005) Données préliminaires sur l’ostréiculture tradition- nelle à la lagune côtière du Bénin (West-Africa). Techni- cal Report, PRECOB/FAST/UAC, Abomey-Calavi.

- PAZH (1999) Rapport sur le programme d’aménagement des Zones Humides.

- FAO (1976) Conférence technique de la FAO sur l’aquaculture. FAO Pêches, N°188, Kyoto, Japan.

- Kinkpe R, Sossa G N, Viaho C C (2005) Lostréiculture traditionnelle: état des lieux et perspectives d’amé Mémoire pour l’obtention du Diplôme d’Etude AgricoleTropicale- DEAT/LAMS.

- Adite A, Abou Y, Sossoukpe E, Fiogbe ED (2013) The oyster farming in the coastal ecosystem of outhern Benin (West Africa: environment, growth and contribution to sustable coasta management. International Journal of Development Research 3(10): 87-94.

- FAO (1982) Coastal aquaculture development perspec- tives in Africa and case studies from other regions.

- Diedhiou M (2008) Contribution à l’étude de la qualité bactériologique des huîtres fraiches dans l’aire marine protégée du petit Kassa (Casamance). Mémoire de DESS Pêche-Aquaculture, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar.

- GCLME (2006) Guinea current large marine ecosystem report. GEF/UNIDO/UNDP/UNEP/US-NOAA, Cotonou.

- PADPPA (2010) Elaboration de la politique nationale des pêches et de l’aquaculture.: PADPPA.

- Quayle D B (1980) Les huîtres sous les tropiques, Ottawa, Canada.

- Torell E, Bilecki D, Owusu A, Crawford B, Beran K, et al. (2019) Assessing the Impacts of Gender Integration in Ghana’s Fisheries Sector. Coastal Management 47(6): 507-526.

- Tzanatos E, Dimitriou E, Papaharisis L, Roussi A, Somarakis S, et al. (2006) Principal socio-economic characteristics of the Greek small-scale coastal fishermen. Ocean & Coastal Management 49(7-8): 511-527.

- GSS (2014) 2010 Population & housing censis. District analytical report. Ga South Municipality. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Oteng-Yeboah A A (1999) Development of management plan for the Densu Delta Ramsar Site. Wildlife Division of Forestry Commission, Ghana.

- Williams M (2008) Why look at fisheries through a gender lens. Development 51: 180-185.

- Hess L, Wang P, Evans J P, Eldridge DJ, McCabe MF, et al. (2012) Dryland ecohydrology and climate change: critical issues and technical advances. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 16: 2585-2603.

- Janha F, Ashcroft M, Mensah J (2017) Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) of the Densu Estuary Oyster Harvesting, Bortianor/Tsokomey, Ga- South Municipal Assembly, Greater Accra Region, Ghana. TRY Oyster Women’s Association. Development Action Association and Hen Mpoano. Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island. SFMP/USAID.

- Pascoe S, Cannard T, Jebreen E, Dichmont C, Schirmer J (2014) Satisfaction with fishing and the desire to leave. AMBIO 1-11.

- Weeratunge N, Snyder KA, Sze CP (2010) Gleaner, fisher, trader, processor: Understanding gendered employment in fisheries and aquaculture. Fish and Fisheries 11(4): 405-420.

- McLusky DS (1989) The estuarine ecosystem. In: Blackie Academic and Professional Ltd, Glasgow, Scotland.

- Ampofo-Yeboah A (2000) Aspects of the fishery, ecology and biology of the freshwater oyster (Etheria sp. Lamarck 1807). Master of Philosophy degree in Zoology, University of Cape Coast.