Bioeconomic Analysis of a Pilot Commercial Production for Frogs (Lithobates Catesbeianus), In Greece

Marianthi Hatziioannou* and Eleni Karatsivou

Department of Ichthyology & Aquatic Environment, University of Thessaly, Greece

Submission:September 20, 2020;Published:November 16, 2020

*Correspondence author: Marianthi Hatziioannou, Department of Ichthyology & Aquatic Environment, School of Agricultural Sciences, University of Thessaly, Fytoko Street, 38 445, Nea Ionia Magnesia, Greece

How to cite this article:Marianthi H, Eleni K. Bioeconomic Analysis of a Pilot Commercial Production for Frogs (Lithobates Catesbeianus), In Greece. Oceanogr Fish Open Access J. 2020; 12(5): 555848. DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2020.12.555848

Abstract

In the present paper the viability of a pilot commercial production of the American bullfrog Lithobates Catesbeianus in Greece was examined. Data were collected through personal interviews (in-depth interviews) with the entrepreneurs of six companies. A comparative presentation of profits and expenses was conducted, and the Net Present Value criterion was applied, as an indication of potential profitability of the investment plan. For the viable scenario NPV, was +464258€ and IRR was 72.8%. A larger produced amount, due to the lower density of the individuals (240 individuals/m2), and the better board management with automatic troughs. One couple of forg legs weighed 140 gr and for the production of 1kg of frog legs seven individuals are required. With food convertibility of 2:1, each animal consumes 750gr of food until it reaches the trading weight of 350gr. Aquaculture is one of the fastest-growing sectors of agriculture in Greece and the development of frog farming interest, both financially as well as in protecting and preserving the natural populations of amphibians.

Keywords: Aquaculture; Frog farming; Bioeconomy; Lithobates Catesbeianus; NPV

Introduction

The harvesting of frogs is, in many parts of the world, linked to the rural, poor populations, as they supplement their nutrition with any protein available, while in many countries, the meat of frogs is considered a dish of luxury. The destruction of their natural habitat, over fishery and climatic changes poses a threat on the amphibians [1,2]. The reduction of natural populations in conjunction with the increasing demand for frogs formed a great interest for the development of frog farming internationally (Brazil, Taiwan, U.S.A, China). In 2008, the global frog production reached 73 109 kg, with China producing 49.1% of it [3]. The universal production of frog legs during 1999- 2008 was approximately 44 106 kg/year. At the same time, Brazil produced 6 105 annually, and was, globally, first in frog legs production for at least ten years [4]. Indonesia exports the largest amount of frog legs to the European Union (EU), with 84% of the total imported from the EU coming from it [5,6]. While Indonesia and Vietnam are the greatest suppliers for the wild-free-fishery frogs, Taiwan, Equator, Mexico, and China are the main exporters for farmed frogs. The annual production on Turkey has been estimated in 8 105 kg [7,8]. During 2000 and 2009, the EU imported a total amount of 46 106 kg of frog legs, primarily from Asia [5].

Among the EU countries, Belgium imported the highest amount of frog legs, followed by France, Holland, Italy, and Spain. If one kg of frog legs is produced from 20-50 individuals the importations of the EU account for 928 million to 2,3 billion frogs. To our knowledge, in our cuntry, there is no study investigating the economic viability of frog farming. In the present paper, the potential for the development of raising and selling frogs on a commercial basis was examined. The research included the emblazonment of frog farming and trading in Greece, as well as the viability evaluation of a pilot commercial production of the American bullfrog Lithobates Catesbeianus (formerly Rana catesbeiana) in Greece. The economic viability of the investment activities addressed in this study, the benefits and investment costs were initially calculated and then the investment criteria were applied. The Net Present Value (NPV) criterion was used in evaluating investment projects. NPV is one of the most popular criteria and an indication of the earning prospects of a project [9].

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

Data were collected through personal interviews (in-depth interviews) with the entrepreneurs of six companies. The selection of non-structured interviews, instead of a questionnaire is due to the heterogeneity of the sample, as far as the size and degree of the organization are concerned. The companies founded in Greece from 1990 until today with commerce object the breeding, trading, and consumption of frog amount to 22. Today, only six of them function, one productive, one in the field of focus and the other four, act as wholesalers of frozen frog legs. The companies that provide their frog legs to the internal markets sell from 20 to 25 euros per kg in luxury restaurants. In this cost, the transportation cost is also included. Wholesaling and exportations seem to be absent.

Analytical Tools

For the economic viability control of the farms to be estimated, the Net Present Value criterion was applied, as an indication of potential profitability of the investment plan. The calculation of the Net Present Value (NPV) arises from the equation:

Here: Cin initial investment, Ft annual net profit, Ν economic life cycle of the investment and d interest rate in present value (desirable capital rate). The criterion of Internal Rate of Return (IRR) was applied, which constitutes the interest rate and results from the equation of the present value of cash flow and the present value of outflow and relates the return of the investment with its capital cost as in [10]. It is defined as the solution of the equation:

Here: NPV the present value, as determined by equation (1), while the indication d=IRR implies that the equation is solved to d. When IRR is bigger than the capital cost, the investment is accepted; when it is smaller it is rejected and when IRR equals the capital cost the investment is marginal and evaluated appropriately. The afore mentioned economic indicators are particularly used for the evaluation of any investment related to the increase of biological reserves and aquaculture as in [11]. The net cash flows were estimated for every year and for a time of ten years. The methodological approach was based on a bioeconomic pattern, the functional parameters of which were determined according to regional data, provided that the national legislation does not pose limitations. The bioeconomic model chosen consists of three inter-dependent sub models: i) biological, ii) management and iii) financial.

Farm Operation Data

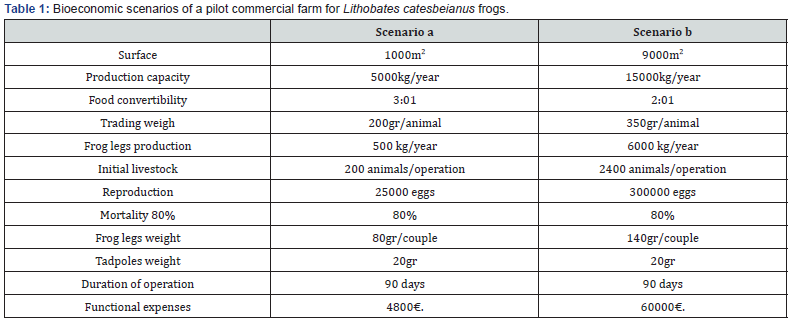

For the study of viability, two scenarios for facilitating and running a pilot farm of Lithobates Catesbeianus were created. The pilot farm is settled in Greece and particularly 200 km from Athens. The two scenarios, (a and b) follow the same farming system, same food (pellets), total fattening duration of three months, same mortality percentage and same number of eggs per begetter. In scenario a, the farm produces 500 kg of frog legs per year and provides them to the domestic market while in b produces 6000 kg of frog legs per year, the most part of them being exported. In scenario a, the farm has a total surface of 4500 m2, with a utilizable extend of 1000m2, while for b, we assumed that the functional range is 9000 m2, as new underground water tanks, closed spaces for reproduction, a biological cleaning system, a water supply and sewage system, as well as offices were constructed. The initial livestock in scenario a was 200 animals and 2400 in b. Finally, in scenario b, a greater animal increasing rate was recorded due to the lower density of individuals in each tank (240 individuals/ m2) and the better board management, with automatic troughs, so there will not be any waste in the supplied food within the tanks. The discount rate was selected to be 5% following other studies with evaluate the validity of investments at primary sector with the same investments risk [11].

Results

The total cost of investment project is estimated to 150.000 €. From this, the greatest part includes the cost of first facilitation (tanks, fencing). The initial monetary sum for the capital motion has not been estimated for first cost. The total production cost consists of food cost required for frog fattening as well as the trading weigh of 200 gr with food convertibility of 3:1 (Table 1). The annual capacity of scenario a, was 5 tons per year (Table 1). The most important cost categories are the purchase of raw material, act, and personnel expenses. The total of functional expenses equaled 4800 €. The annual sales of frog legs with 25 € per kilo, with a stable price within five years and stable annual produced amount. The average exploitation of the unit in zero point arises to 67.4 % of the defined capacity. From the results, it emerges that the negative monetary flow for the constructive period (Year 0) equals the total of the sharing capital. The Net Present Value (N.P.V) is estimated in (- 34.500 €) and the Internal Return (I.R.R) was negative (– 3,9%).

From the comparison of the economic scenarios of an enterprise - farm of L. catesbeianus frogs- it was proven that scenario b was viable (Table 1). The NPV, is positive and equal to (+464258€) and the IRR is positive and equal to 72.8%. The average exploitation of the scenario is 6% of the production. A greater increase rate of the animals is observed, as well as a larger produced amount, due to the lower density of the individuals in each tank (240 individuals / m2), and the better board management with automatic troughs, so that the supplied food will not be watsed within the tanks. One couple of forg legs weighed 140 gr and for the production of 1kg of frog legs seven individuals are required. With food convertibility of 2:1, each animal consumes 750gr of food until it reaches the trading weight of 350gr (Table 1).

Conclusion

American bullfrog L. catesbeianus is an alien invasive species but it is a widespread one of the delicacies of international gastronomy that has increased worldwide consumption. It is widely known that aquaculture of the L. catesbeianus required special handling for all stages of the life cycle, including incubation, the development of tadpoles and the fattening of frogs until they acquire the trading size and the choice and preservation of certain individuals as begetters (ratio of begetters one male to five females) [12]. The trading weight of L. catesbeianus is 175gr (70 gr in frog legs) and is acquired in the third month of breeding. When aimed to be used for its skin, the slaughter is conducted in weight of 250-300 gr [12]. Trading farming of frogs is attractive if exercised with good percentage of animal food convertibility and favorable prices for market placement resulting to the meat being sold as gastronomical product [13] mention that the viability of an enterprise in Brazil is succeeded only with food convertibility ≤ 1.5:1 in fattening and ≤ 2:1 in tadpoles in conjunction with a high price in frog legs sales.

In the same study, the IRR was 41.69% with repayment in 2.44 years, results usually used in the field of aquaculture. In similar studies it was estimated that the total cost of initial facilitation of farms was $120.000, which can vary depending on the amount of raw material, design of tanks, but also skills of the farmer himself in providing individual work [14]. Aquaculture is one of the fastest-growing sectors of agriculture in Greece and the development of frog farming demonstrates and interest, both financially as well as in protecting and preserving the natural populations of amphibians [15]. In Greece, frog legs constitute a traditional food, particularly connected to Lake Pamvotida, where one comes across many restaurants serving them as specialty. Future research can focus on fields like the development of technical knowledge for the Greek edible frogs.

References

- Stuart SN, Chanson JS, Cox NA, Young BE, Rodrigues ASL,et al. (2004) Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306(5702):1783-1786.

- Rowley J, Brown R, Raoul B, Kursrini M, Inger R, et al. (2009) Impending Conservation Crisis for Southeast Asian Amphibians. Biology Letters 1-3.

- LoperaBarrero NM, Ribeiro RP,Povh JA, Mendez LDV, PovedaParra AR, et al. (2010) As principaisespéciesproduzidas no Brasil. Guaiba: Agrolivros 143-203.

- FAO Statistics (2010) Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations helping to build a world without hunger. Fisheries and Aquaculture Department.

- Eurostat (2010) Database of the European Commission, external trade in frog legs (product groups 02082000 and 02089070: imports and exports.

- Kusrini MD, Alford RA (2006) Indonesia’s Export of Frog’s Legs. Traffic Bulletin 21: 13-24.

- Ozogul F,Ozogul Y,Olgunoglu AI, Boga EK (2008) Comparison of fatty acid, mineral and proximate composition of body and legs of edible frog (Rana esculenta) Int J Food Sci and Nutr 59(7-8): 558-565

- Tokur B,Gurbuz RD, Ozyurt G (2008) Nutritional composition of frog (Rana esculanta) waste meal. Bioresource Technology 99(5): 1332-1338

- Ryan PA,Eyan GP (2002) Capital budgeting practices of the Fortune 1000: How have things changed?”.Journal of Business and Management 8:152-168.

- Fama EF, French KR (1999) The Corporate Cost of Capital and the Return on Corporate Investment.The Journal of Finance54:1939-1967.

- Garcia Garcia J, Garcia Garcia B (2006) An econometric viability model for ongrowing sole (Solea senegalensis) in tanks using pumped well sea water.Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 4:304-315.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme, Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1862).

- Moreira CR, Henriques MB, Ferreira CM (2013) Frog farms as proposed in agribusiness aquaculture: economic viability based in feed conversion. Bol Inst Pesca São Paulo 39(4): 389-399.

- Helfrich LA, Neves RJ, Parkhurst J (2009) Commercial Frog Farming, Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University 420-255.

- Schuler J, Sattler C,Helmecke A, Zander P,Uthes S, et al. (2013) The economic efficiency of concervation measures for amphibians in organic farming Results from bio-economic modeling.Journal of Enviromental management 114: 404-413.