Presence of the Seahorse Hippocampus reidi (Pisces: Syngnathidae) In Diet of Marine Fish in Northeastern Brazil

Rosana Beatriz Silveira1*, José Rodrigo Santos Silva1,2

1Laboratório de Aquicultura Marinha, Instituto Hippocampus, Brazil

2Departamento de Estatística e Ciências Atuárias, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Brazil

Submission:June 24, 2020; Published:July 20, 2020

*Correspondence author: Rosana Beatriz Silveira, Laboratório de Aquicultura Marinha, Projeto Hippocampus, Brazil

How to cite this article:Rosana Beatriz Silveira, José Rodrigo Santos Silva. Presence of the Seahorse Hippocampus reidi (Pisces: Syngnathidae) In Diet of Marine Fish in Northeastern Brazil. Oceanogr Fish Open Access J. 2020; 12(1): 555830. DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2020.12.555830

Abstract

Seahorses are species that are globally threatened with extinction because of their capture for the ornamental fish trade and traditional medicine and because of suffering from environmental degradation and habitat loss. Moreover, they make up the diet of many animals, including fishes. Seahorses are often bycatch in net fishing, and rarely reported as bycatch in fishing with hooks, but they are prey of fish that are caught in this way. The analysis of the stomach contents of fish caught in troll and longline fishing, revealed the presence of Hippocampus reidi as a food item of Cephalopholis fulva and Thunnus atlanticus.

Keywords:Cephalopholis fulva; Thunnus atlanticus; Longline fishing; Trolling line

Introduction

Seahorses (Syngnathidae: Hippocampus) are globally endangered species [1], where they are targets of the trade for ornamental fish, traditional medicine, handicrafts, charms and others [2]. Of course, they are prey for several animals, including other fish, where they are regular or occasional food for some species, which can be verified by the analysis of stomach contents [3,4]. Seahorses compose the bycatch of fisheries with gillnets and mainly trawls but they can be caught indirectly when they are eaten by other fish that are targets of the most varied fishing gear [5-8]. Of the various methods of fishing with hooks, mode “pargueira” is used to catch bottom fishes, which live on rocky, gravel or coral substrates, such as grouper (Epinephelinae), while mode “corrico” is done with baited fishing lines in a moving boat and is intended for the capture of sea bass (Centropomidae) and mackerel (Scombridae), among others [9,10]. We report here, these two types of fishing, whose target fish had ingested seahorses.

Materials and Methods

Two excursions were carried out by the commercial fishing boat Deep Drop (Pernambuco, Brazil) from the states of Alagoas/Pernambuco border to the beach of Porto de Galinhas (Pernambuco), fishing exclusively with hooks. A fishery of “pargueiras” aimed at the common seabream Pagrus pagrus (Sparidae) occurred at a depth of 130 m, whereas the other fishing method used was “corrico” with hooks at 70 m; both were performed 30 to 35 km from the coast, following the slope of the continental shelf of Pernambuco [11]. The seahorses were identified according to Silveira et al. [12] and their predators according to Lessa & Nobrega [13]. These were sporadic records; it was not a systematic investigation.

Results and Discussion

In the “pargueiras” mode, a coney (Cephalopholis fulva; Serranidae) weighing 500 g and measuring 23 cm in total length (TL) was captured. A seahorse specimen was found inside the mouth and still alive, it had been collected and frozen by the fisherman, with the other fishing catch. In the “corrico” mode, at 70 m deep resulted in the capture of a blackfin tuna (Thunnus atlanticus; Scombridae) weighing 1980 g, whose stomach contents revealed two specimens of partially digested seahorses, but with the skeleton in good condition, allowing the identification of the species.

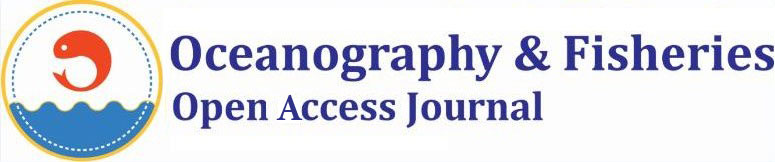

The seahorse found inside the mouth of the coney was a female of Hippocampus reidi (Figure 1, A), 9.4 cm height (measured linearly from the top of the head to the tip of the stretched tail). The two specimens collected from the stomach of the blackfin tuna were 6.5 and 7.0 cm tall, both H. reidi females (Figure 1, B). Only the seahorse found in the coney was donated to the Project Hippocampus, contributing to its collection, the others were used by fishermen to make tea for “childhood fatigue” (asthma).

Cephalopholis fulva is distributed from North Carolina (USA) to southeastern Brazil, being relatively common on the Northeastern coast of Brazil [14-16]. Its diet is composed of small fish and crustaceans and is a daytime predator that exhibits a sit-and-wait strategy, staying close to the bottom [17-19]. Predation of juveniles of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) by the coney has been observed, along with annelids, which were found in their stomach contents [20]. According to Oliveira et al. [21], the coney is fished in the range of 100 to 200 m deep, which is in agreement with the range where the fish that contained the seahorse in its mouth was fished. It is not uncommon demersal fish prey on seahorses and other Syngnathidae, Kleiber et al. [3] conducted an extensive review of seahorses and pipefish as food for other animals and found a diversity of predators, comprising 82 species, including invertebrates, fish, sea turtles, waterfowl and marine mammals. For C. fulva, this was the first record of predation on seahorses.

Thunnus atlanticus is distributed from Massachusetts (USA) to southeastern Brazil and is found in coastal waters with a temperature above 20°C. It is an epipelagic species and feeds on fish, squid and crustaceans, usually occurring in a range of 20 -60 m depth [22-24]. Kleiber et al. [3] were found T. albacares, T. thynnus and Thunnus sp. preying on seahorses, so this is the first record for T. atlanticus. The predation of the seahorse by the coney, a fish that stays near the bottom is easily understandable, since both explore the bottom. However, the fact that a tuna (epipelagic) swallowed two seahorses (demersal), suggested that the displacement of these Syngnathidae in the water column occurs by adherence to floating vegetation [3,25], favoring settlements in new environments or making them occasional prey for other resident animals or travelers from the open sea. This contribution is the first record of H. reidi predation by Cephalopholis fulva and Thunnus atlanticus in Brazilian waters.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Leonardo Blanke Samson of Peixaria e Restaurante Noronha de Porto de Galinhas, Ipojuca, PE for providing the material examined and other information about the fishing. Dr A Leyva (USA) helped with English translation and editing.

References

- IUCN (2017) IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- Vincent ACJ (1996) The International Trade in Seahorses. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge.

- Kleiber D, Blight LK, Caldwell IR, Vincent ACJ (2011) The importance of seahorses and pipefishes in the diet of marine animals. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 21: 205-223.

- Mastrangelli A, Silveira RB, Burato M, et al (2019) First report of Lepidochelys olivacea feeding on Hippocampus patagonicus in Brazil. Marine Turtle Newsletter 159: 26-27.

- Baum JK, Meeuwig JJ, Vincent ACJ (2003) Bycatch of lined seahorses (Hippocampus erectus) in a Gulf of Mexico shrimp trawl fishery. Fishery Bulletin 101: 721-731.

- Buchheister A (2013) Structure, Drivers, and Trophic Interactions of the Demersal Fish Community in Chesapeake Bay (Dissertation). The College of William and Mary in Virginia.

- Choo CK, Liew HC (2005) Exploitation and Trade in Seahorses in Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Nature Journal 57(1): 57-66.

- Silveira RB (2011) Registros de cavalos-marinhos (Syngnathidae: Hippocampus) ao longo da costa Brasileira. Oecologia Australis 15: 316-325.

- Lessa RP, Bezerra Jr JL, Nóbrega MF (2004) Dinâmica de Populações e Avaliação de Estoques dos Recursos Pesqueiros da Região Nordeste, (2nd edn). Programa de Avaliação do Potencial Sustentável dos Recursos Vivos da Zona Econômica Exclusiva (REVIZEE), Sub-Comitê Regional Nordeste (SCORE - NE), Recife, Brazil.

- Netto R de F, Beneditto APM Di (2007) Diversidade de artefatos da pesca artesanal marinha do Espírito Santo. Biotemas 20: 107-119.

- Manso V do AV, Correa ICS, Guerra NC (2003) Morfologia e sedimentologia da Plataforma Continental Interna entre as Praias Porto de Galinhas e Campos-Litoral Sul de Pernambuco, Brasil. Revista Pesquisa em Geociências 30: 17-25.

- Silveira RB, Siccha-Ramirez R, Silva JRS, Oliveira C (2014) Morphological and molecular evidence for the occurrence of three Hippocampus species (Teleostei: Syngnathidae) in Brazil. Zootaxa 3861(4): 317-332.

- Lessa R, Nóbrega MF de (2000) Guia de Identificação de Peixes Marinhos da Região Nordeste. Programa Revizee/Score Nordeste, Recife, Brazil.

- Ferreira BP, Gaspar ALB, Marques S, et al (2008) Cephalopholis fulva. IUCN Red List Threat Species 2008: e.T132806A3456570.

- Ferreira CEL, Floeter SR, Gasparini JL, B P Ferreira J C Joyeux (2004) Trophic structure patterns of Brazilian reef fishes: a latitudinal comparison. Journal of Biogeography 31(7): 1093-1106.

- Fredou T, Ferreira B, Letourneur Y (2006) A univariate and multivariate study of reef fisheries off northeastern Brazil. ICES Journal of Marine Science 63: 883-896.

- Francini-Filho RB, Moura RL, Sazima I (2000) Cleaning by the wrasse Thalassoma noronhanum, with two records of predation by its grouper client Cephalopholis fulva. Journal of Fish Biology 56: 802-809.

- Sazima I (1986) Similarities in feeding behaviour between some marine and freshwater fishes in two tropical communities. Journal of Fish Biology 29: 53-65.

- Sazima I, Krajewski JP, Bonaldo RM, Sazima C (2005) Wolf in a sheep’s clothes: juvenile coney (Cephalopholis fulva) as an aggressive mimic of the brown chromis (Chromis multilineata). Neotropical Ichthyology 3: 315-318.

- Coelho F do N, Pinheiro HT, Santos RG dos, Cristiano Queiroz de Albuquerque (2012) Spatial distribution and diet of Cephalopholis fulva (Ephinephelidae) at Trindade Island, Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology 10: 383-388.

- Oliveira I da M, Hazin F, Oliveira V de S, Fábio Geber, Ronaldo Barradas (2007) Distribution and relative abundance of deep-fishes caught by artisanal bottom longline off Pernambuco state, Brazil. Boletim do Instituto de PEsca 33: 183-193.

- Vieira KR, Oliveira JEL, Barbalho MC, Aldatz JP (2005) Aspects of the dynamic population of Blackfin Tuna (Thunnus atlanticus - Lesson, 1831) caught in the northeast Brazil. International Commission for the conservation of Atlantic Tuna 58: 1623-1628.

- Freire K (2009) Thunnus atlanticus. In: Lessa R, Nóbrega MF, Bezerra Jr JL (eds.). Dinâmica de populações e avaliação dos recursos pesqueiros da região Nordeste, Martins & Cordeiro, Fortaleza, Brazil, Pp: 275-286.

- Collette B, Amorim A F, Boustany A, et al (2011) Thunnus atlanticus. IUCN Red List Threat Species 2011:e.T155276A4764002.

- Luzzatto DC, Estalles ML, Díaz de Astarloa JM (2013) Rafting seahorses: the presence of juvenile Hippocampus patagonicus in floating debris. Journal of Fish Biology 83:677-681.