Multi-Center Evaluation of a Next-Generation Powered Stapler in Gastric Procedures

Burch M1, Carlin AM2, Englehardt R3, Kellogg T4, Lewis M5 and Veldhuis P5*

1Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA

2Henry Ford Health, Detroit, MI

3Bariatric Medical Institute of TX, San Antonio, TX

4Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN;

5Ethicon Inc., Cincinnati, OH

Submission:November 11, 2025;Published:November 19, 2025

*Corresponding author:Paula Veldhuis, Ethicon Inc., 4545 Creek Rd., Cincinnati, OH 45242, 513-337-7000

How to cite this article:Burch M, Carlin AM, Englehardt R, Kellogg T, Lewis M, et al. Multi-Center Evaluation of a Next-Generation Powered Stapler in Gastric Procedures. Open Access J Surg. 2025; 17(1): 555951. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2025.17.555951.

Abstract

Introduction: Stapling devices are essential in modern surgery, evolving from traditional suturing techniques to powered variants enhancing surgical outcomes. The ECHELON 3000 Stapler and Reload System (ECH3000) was developed to address continued challenges in laparoscopic surgery by optimizing staple formation while minimizing complications. Staple line leaks (SLs), bleeding, and surgical site infections (SSIs) remain serious concerns post-gastric surgeries, particularly in sleeve gastrectomy.

Methods: The objective of this post-market, prospective study was to evaluate the safety and performance of the ECH3000 during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Conducted across four centers in the United States, the study collected data on patient demographics, intraoperative outcomes, and adverse events (AEs) through a 30-day follow-up. The primary endpoint was the incidence of specific serious adverse events (SLs, SSIs, blood loss, hematoma; SAEs) related to the device.

Results: A total of 117 LSG procedures were performed in patients with a mean age of 44.2 years and BMI of 45.9 kg/m². The mean operative time was 79.0 minutes, with an estimated mean blood loss of 19.0 mL, and no conversions to open surgery. There were zero (0.0%) specific device-related SAEs reported within the follow-up period, while overall AEs were reported in 5.1% of cases. Of the 690 total firings of the stapler, surgeons reported acceptable staple line integrity in 99.6% of those firings.

Conclusions: The results suggest that the ECH3000 is a reliable device for achieving staple line integrity in LSG with no occurrences of SLs, postoperative bleeding, or SSIs.

Keywords: Echelon 3000; Endopath Stapler; Gastric Surgery; Gripping Surface Technology

Abbreviations: SG: Sleeve Gastrectomy; LSG: Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy; SLs: Staple Line Leaks; SSIs: Surgical Site Infections; GST: Gripping Surface Technology; IFU: Instructions for Use; SAEs: Serious Adverse Events; AEs: Adverse Events; BMI: Body Mass Index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI: Confidence Interval; SLR: Staple Line Reinforcement

Introduction

Stapling devices are indispensable tools in modern surgery and have evolved significantly since their advent in the early 1900s by providing reliable and efficient alternatives to traditional suturing techniques [1]. Contemporary powered staplers utilized for tissue/organ transection, resection, and anastomoses have been shown to offer reliable performance leading to improved surgical outcomes including lower incidence of leaks and bleeding, and shorter hospital stays [2,3]. These updated powered staplers have further aided in improving outcomes by providing easier access to challenging anatomical areas while at the same time providing adequate tissue compression to ensure acceptable staple line integrity [4,5].

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) has emerged as the most commonly performed bariatric operation (57.4%) in the United States [6-8]. While complication rates remain relatively low for sleeve gastrectomy, it is not without risks including leak at the staple line, hemorrhage, and infection. Bleeding events following sleeve gastrectomy, despite being rare (around 2%), are amongst the most serious. One single-institution study assessing 664 laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies (LSG) reported a postoperative bleeding rate of 2.0% [9]. A retrospective study reviewing 1,261 patients post SG reported a bleeding rate of 2.1% [10]. Similarly, staple line leaks (SLs) and surgical site infections (SSIs) pose risk for post-operative morbidity and mortality. In the post sleeve gastrectomy population, for example, one systematic analysis involving 4,888 patients found that the overall leak rate to be 2.4% in patients with a BMI <50 kg/m2 and slightly higher for individuals with >50 kg/m2 BMI (2.9%) [11]. Overall, post-operative leaks in LSG are reported in 1% to 7% of patients and are associated with increased postoperative mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and higher rates of reoperation [12-17]. Likewise, surgical site infections (SSIs) following LSG have a reported incidence of 0.4% to 7.6% and are also associated with extended hospital stay, increased readmission, and increased cost and mortality [18-20].

Consistent tissue compression is essential for optimal staple formation and to minimize the risk of complications including intraoperative bleeding and anastomotic/staple line leakage [21,22]. Building upon previous device iterations including the ECHELON+ and the ECHELON FLEX staplers, the ECHELON 3000 Stapler (ECH3000), introduced in 2022, was engineered to address continued challenges encountered during laparoscopic surgery including precise tissue transection, staple line integrity, consistent staple formation in variable thickness tissues and improved access in tight spaces [23]. The ECH3000, which incorporates powered continuous articulation, a wide articulation span of over 110°, dynamic firing, larger jaw aperture, shorter articulation joint length, refined anvil curvature and tapered staple pockets designed to better align tissue during compression improving staple formation, and a gripping surface technology (GST) reload system aimed to stabilize tissue during staple firing [24-26]. The ECH3000 deploys 6 staggered rows of titanium staples, 3 on either side of the cut line. Benchtop testing in porcine models has shown that the ECH3000 stapler achieves tighter seals with fewer leaks at critical pressures as well as a lower rate of malformed staples compared to the Signia Powered Stapler (Medtronic, Fridley, MN) [26]. Given the recent market introduction of this device and the paucity of real-world data regarding its use, the study presented here was undertaken to collect observational data of the ECH3000 when used in patients undergoing LSG.

Methods

Study design

This prospective, post-market study included four participating clinical centers in the United States. Before the initiation of the study, each participating site obtained Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee approval, and subsequently all subjects provided written informed consent. This study was conducted adhering to the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and any other local or country regulatory requirements. The investigators performed each procedure in accordance with the device-specific Instructions for Use (IFU) and adhered to the standard surgical protocols established by their respective institutions.

Study objective and endpoints

The objective of this study was to evaluate the safety and performance of the ECH3000 in conjunction with its reload(s) system. The primary endpoint was the incidence of subjects experiencing pre-defined device-related serious adverse events (SAEs) through 30-day (±14 days) post-procedure. SAEs were defined as the occurrence of 1. post-operative infection deemed related to device and/or to the staple line; 2. post-operative hematoma, procedural hemorrhage, or blood transfusion; and/or 3. post-operative gastric leak related to the staple-line. Secondary endpoints included all device- or procedure-related adverse events (AEs) and other reported SAEs.

Patients

Both pediatric and adult patients presenting for sleeve gastrectomy (SG) where the ECH3000 and reload system was scheduled to be utilized were eligible to enroll. Patients were excluded if the proposed surgical procedure was a revision/ reoperation for the same indication, surgical stapling was contraindicated, for the same indication or a reoperation occurring at the same anatomical site.

Device

The ECHELON™ 3000 Stapler and accompanying reloads (Ethicon, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) act together as a system. Devices included 3 shaft length variants (compact, standard, long) within each of the ECH3000 45 mm and 60 mm staplers, any of which length would not impact performance: ECH45C, ECH45S, ECH45L, ECH60C, ECH60S, ECH60L with the White, Blue, Gold, Green, and Black GST Stapler reloads.

Surgeons

Procedures were completed per their institution’s standard operating procedure by four experienced surgeons who had been trained on the proper use of the stapler/reloads per the device instructions for use.

Data collection and study variables

Baseline data collection included demographic variables: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification. The primary indication for surgery was documented. Intraoperative data collected included procedure performed, staple line reenforcement utilization, total number of study devices used during each procedure, interventions for staple-line bleeding, estimated blood loss, and requirement for intra-operative blood transfusions. Additional data collected included any concomitant procedures performed and hospital length of stay. For the purposes of this study, staple line integrity was defined as the absence of irregular, missing, or malformed staples.

Statistics

Subject disposition was summarized using counts and percentages. Descriptive summary statistics of subject demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, and BMI) were calculated. Similar summaries were provided for baseline and surgical characteristics including surgical procedure, ASA physical status classification, procedure duration, and additional surgical variables. The number and percentage of subjects experiencing an occurrence of the primary endpoint were summarized and an exact 95% confidence interval (CI) estimated. Frequency counts and percentages were provided for all device-related, procedurerelated AEs and SAEs. Data analysis was performed using SAS v9.4M6 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

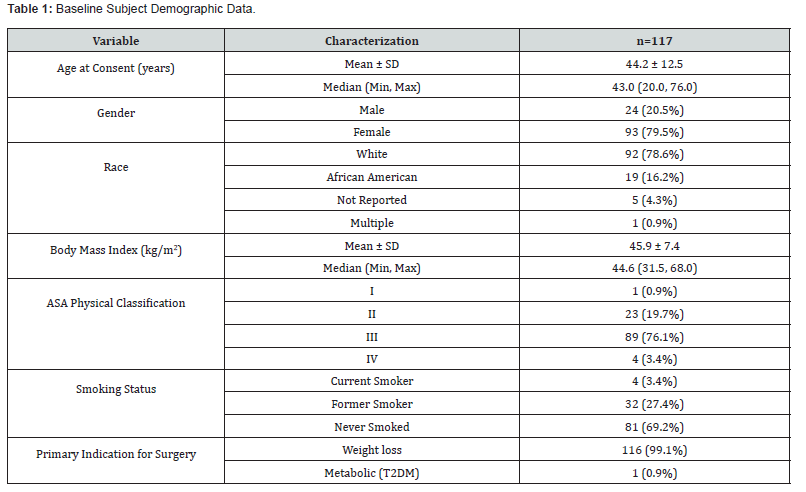

Between March 23, 2023, and January 8, 2025, the ECH3000 was used in 117 sleeve gastrectomies (43 robot-assisted). Subjects ranged between 20 and 76 years of age (mean 44.2 ± 12.5 years) and were primarily female (79.5%) with a mean BMI of 45.9 kg/m2. In 89 cases (76.1%), subjects were reported to have an ASA III. There were four current smokers (3.4%), 32 (27.4%) former smokers, and 81 (69.2%) who had never smoked (Table 1). Medical histories obtained disclosed: gastroesophageal reflux disease in 39.3% of subjects, diabetes mellitus in 2.6%, hypertension in 21.4%, hypercholesterolemia in 7.7%, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 0.9%, non-alcoholic fatty liver in 7.7%, and cardiac disorders in 13.7%. Of the initial cohort, one subject was eventually lost to follow-up.

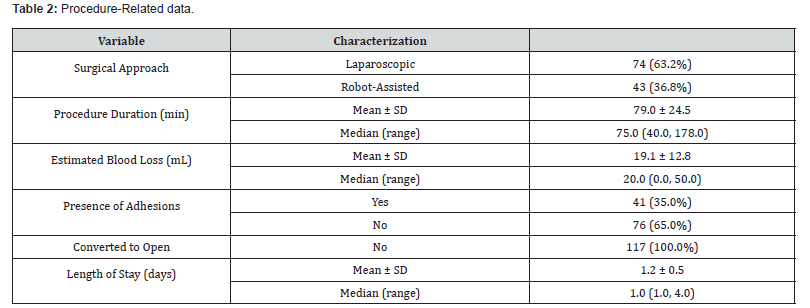

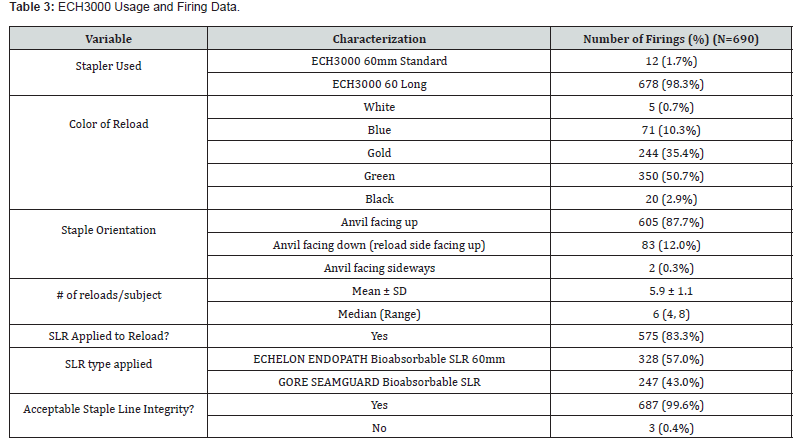

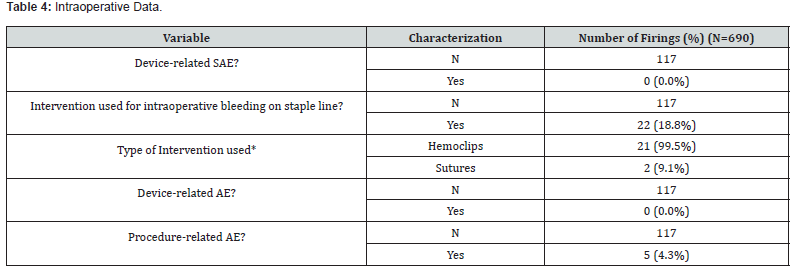

Intraoperative details are presented in (Table 2). The mean operative procedure time was 79.0 min (40-178 min range) with an estimated mean blood loss of 19.1 mL (0 - 50 mL range). Adhesions were reported in 41 cases (35.0%). No procedure required a conversion to open. The mean length of stay was 1.2 days (1.0 - 4.0-day range) (Table 3). summarizes the use of the ECH3000. Of the 690 total firings of the stapler, the ECH3000 60mm Long Stapler was used in most (678, 98.3%) with the remaining 12 (1.7%) being the 60mm Standard length. The majority of reloads were either Gold (35.4%) or Green (50.7%) (Table 4). Surgeons reported acceptable staple line integrity in 687/690 of the firings (99.6%). If the staple line integrity was deemed “not acceptable”, surgeons were further queried about the cause which yielded the following responses: 1 missing staple in a single reload and 2 malformed staples in 2 reloads.

*Multiple responses permitted

In respect to the primary study endpoint, there were zero (0) reported device-related SAEs through the 30-day follow-up post-operative period (C.I. 0.00%, 3.10%). Surgeons were queried regarding signs of bleeding and infection or symptoms of infection related to the device and/or to the study device staple line from time of procedure to discharge. There were zero (0.0%) reports of post-operative hematoma, procedural hemorrhage, blood transfusions, or post-operative infection. Similarly, there were no reported occurrences of gastric leak at the staple line. One subject received a red blood cell transfusion post-discharge assessed not related to the device or procedure but to an anticoagulation drug given for atrial fibrillation, blood clotting disorder, and venous stasis disease.

Staple line reinforcement (SLR) was utilized in 103 cases (88.0%) with a total of 690 firings. Of those, the ECHELON ENDOPATH bioabsorbable SLR accounted for 328 firings (57.0%) and GORE SEAMGUARD bioabsorbable SLR for 247 firings (43.0%) In this subset, intervention to obtain hemostasis for intraoperative bleeding along the staple line was required in 22 cases (18.8%) comprised of 21 hemoclips and 2 sutures. Of these 22, the presence of adhesions was reported in 12 cases (54.5%), none were converted to an open surgery and the median estimated blood loss was 30.0 mL (range 0.0, 40.0). No subject in this subset required an intraoperative blood transfusion.

A total of six AEs in six subjects (5.1%) occurred during the course of the study, none of which were deemed device related. Two of these AEs were classified as serious (abdominal wall hematoma and small bowel obstruction). One SAE (small intestinal obstruction) and 5 AEs were deemed related to the study procedure. No deaths occurred during the study period. Concomitant procedures were performed in 14.5% of subjects, one of which was performed due to an AE (a small bowel obstruction requiring a small bowel resection). The majority of concomitant procedures were hernia repairs (n=11), followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n=2), lysis of adhesions (n=1), gastric mass excision (n=1), and a Coude foley placement (n=1).

Discussion

This observational post-market study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the ECH3000 in the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy population in which gastric leak remains one of the most serious potential complications [27,28]. While the time to diagnosis of gastric leak can vary significantly in LSG, most leaks develop within 15 days of the procedure and thus patients were followed 30 days post-surgery [29]. In the current study there were no reports of specific device-related serious adverse events relating to the primary endpoint (staple line leak, hemorrhage, and postoperative infection) in the 117 procedures performed. This absence of pre-defined specific device-related SAEs aligns with those reported in the literature. Specifically in terms of SLs, one systematic review and meta-analysis including 8,922 LSG cases and encompassing 112 studies, reported a 2.2% leak rate [12]. Similarly, one retrospective review at 8 bariatric centers including 2,834 patients reported a 1.5% leak rate [27]. In other studies, though, rates as high as 5.3% have been reported [30]. The study presented here had no reports of hemorrhage post-LSG (0.0%) through the 30-day follow-up period, which is not unlike than the Fourth International Consensus Summit on Sleeve Gastrectomy which yielded a 1.8% bleeding rate [14]. Other literature suggests bleeding rates post-LSG can be as high as 4.0% [31].

The use of staple line reinforcement in the current study reflects surgeon preference and since it was the aim of the authors to obtain real-world usage data, surgeons were instructed to perform LSG per their standard operating procedures. SLR, which may reduce the risk of bleeding, leak and overall complications, was utilized in 88.3% (575/690) of the reloads [32]. While the jury is still out regarding the size of improvement linked to the use of SLR, surgeons who choose to reinforce the staple line often cite literature suggesting reinforcement materials may reduce the risk of intraoperative bleeding and, in some studies, shorten hospital stays or lower perioperative morbidity [32-34].

There were no reported hematomas in the current study. While hematoma formation is rare in gastric stapling literature, the lower incidence of bleeding complications observed with previous Echelon systems employing GST may reduce the risk of hematoma development [35]. Clinical evidence suggests that the GST system is associated with a lower rate of hemostasis-related complications. One large retrospective matched study reports a bleeding complication rate of 0.61% for ECH3000 compared to 2.24% (P=0.0012) for a competing stapling system (Signia) indicating a reduction in intra- and post-operative hemorrhage, and by extension potentially the need for blood transfusions [35].

In the current study, in more than 99% of cases, staple line integrity was acceptable excepting 3 firings (two subjects) where 1 missing and 2 malformed staples were observed highlighting the devices’ effectiveness. Achieving consistent and properly formed staples is critical to staple line integrity, hemostasis and prevention of complications such as bleeding and leaks. GST reloads provide an atraumatic grip while holding tissue securely in place during firing which in previous studies has shown to significantly reduce slippage [24]. The system’s two-stage compression and firing compresses tissue before and during firing to reduce the risk of tissue trauma while creating reliable staple formation. Benchtop testing of the ECH3000 demonstrated that the updated device design yielded fewer malformed staples when compared to competitor devices [26].

Additionally, the ECH3000 staple system was successful in accommodating the variability of the gastric wall thicknesses encountered in LSG with the preponderance of cartridges selected being green (recommended range of 1.75 to 3.25 mm thickness) and gold (recommended range of 1.5 to 3.0 mm thickness). Preoperative abdominal adhesions in gastric surgery are noted to be higher in patients with prior abdominal surgery and can pose significant challenges during dissection increasing complication risks [36]. In the current study, preoperative abdominal adhesions were present in 35% of patients. Despite this rate of preexisting stomach adhesions, the ECH3000 functioned as intended throughout all procedures with no device-related SAEs which suggests the safety of the device and the feasibility of utilizing it in LSG patients with pre-existing adhesions and in other challenging conditions.

Overall, six adverse events occurred in 117 subjects (5.1%), 5 of which were deemed to be device-related and not devicerelated. This incidence aligns with overall complication rate of 5.0% reported in existing literature [37]. One of these AEs (a small bowel obstruction) led to a bowel resection occurring after discharge (visit 2) and prior to visit 3. The event was listed as resolved/recovered after 12 days. One subject required a blood transfusion after discharge which was deemed related to an anticoagulant prescribed for atrial fibrillation, blood clotting disorder, and venous stasis disease.

One potential limitation of this study was its single-arm design with no comparator though the goal of the researchers was to gain insight into the real-world use of the ECH3000. Additionally, surgeons were not consistently queried about their perception of the usability of the device. The new articulation may have contributed to the lower rate of AEs and SAEs compared to previous models, but as this feedback was subjective in nature it is difficult to quantify that effect. Strengths of this study include its multi-center, prospective design which allowed for real-world observational data to be collected, and the inclusion of consecutively screened subjects to minimize selection bias. Additional research is warranted to investigate further its use in other surgical specialties.

Conclusion

The absence of any device-related serious adverse events suggests that the ECH3000 provides an acceptable sealing and safety profile in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Conflict of Interest

ML and PV are employed by Ethicon, Inc. Study site investigators (MB, AC, RE, RK) were provided with surgical devices, and funding for patient recruitment and data collection.

References

- Gaidry AD, Tremblay L, Nakayama D, Ignacio RC (2019) The History of Surgical Staplers: A Combination of Hungarian, Russian, and American Innovation. The American surgeon 85(6): 563-566.

- Martín-Arévalo J, Moro-Valdezate D, Pérez-Santiago L, López-Mozos F, Peña CJ, et al. (2025) Current evidence on powered versus manual circular staplers in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 40 (1): 13.

- Sturiale A, Fabiani B, Menconi C, Cafaro D, Celedon Porzio F, et al. (2021) Stapled Surgery for Hemorrhoidal Prolapse: From the Beginning to Modern Times. Reviews on recent clinical trials 16(1): 39-53.

- Gutierrez M, Jamous N, Petraiuolo W, Roy S (2023) Global Surgeon Opinion on the Impact of Surgical Access When Using Endo cutters Across Specialties. Journal of health economics and outcomes research 10(2): 62-71.

- Pla-Martí V, Martín-Arévalo J, Moro-Valdezate D, García-Botello S, Mora-Oliver I, et al. (2020) Impact of the novel powered circular stapler on risk of anastomotic leakage in colorectal anastomosis: a propensity score-matched study. Tech Coloproctol 25(3): 279-284

- Tish S, Corcelles R (2024) The Art of Sleeve Gastrectomy. Journal of Clinical Medicine 13(7): 1954.

- Friedrich MJ (2017) Global Obesity Epidemic Worsening. JAMA 318(7): 603-603.

- Clapp B, Ponce J, Corbett J, Ghanem OM, Kurian M, et al. (2024) American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2022 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surgery for obesity and related diseases: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery 20(5): 425-431.

- Khoursheed M, Al-Bader I, Mouzannar A, Ashraf A, Bahzad Y, et al. (2016) Postoperative Bleeding and Leakage After Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Single-Center Experience. Obes Surg 26(12): 2944-2951.

- Bransen J, Gilissen LP, van Rutte PW, Nienhuijs SW (2015) Costs of Leaks and Bleeding After Sleeve Gastrectomies. Obes Surg 25(10): 1767-1771.

- Aurora AR, Khaitan L, Saber AA (2012) Sleeve gastrectomy and the risk of leak: a systematic analysis of 4,888 patients. Surgical endoscopy 26(6): 1509-1515.

- Parikh M, Issa R, McCrillis A, Saunders JK, Ude-Welcome A, et al. (2013) Surgical strategies that may decrease leak after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 9991 cases. Ann Surg 257(2): 231-237.

- Rosenthal RJ, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, Baker RS, Basso N, et al. (2012) International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surgery for obesity and related diseases: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery 8(1): 8-19.

- Gagner M, Deitel M, Erickson AL, Crosby RD (2013) Survey on laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at the Fourth International Consensus Summit on Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg 23(12): 2013-2017.

- Juza RM, Haluck RS, Pauli EM, Rogers AM, Won EJ, et al. (2015) Gastric sleeve leak: a single institution's experience with early combined laparoendoscopic management. Surgery for obesity and related diseases: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery 11(1): 60-64.

- Shikora SA, Mahoney CB (2015) Clinical Benefit of Gastric Staple Line Reinforcement (SLR) in Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Meta-analysis. Obes Surg 25(7): 1133-1141.

- Sroka G, Milevski D, Shteinberg D, Mady H, Matter I (2015) Minimizing Hemorrhagic Complications in Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy-a Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes Surg 25(9): 1577-1583.

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Oller I, Llavero C, Arroyo A, Muñoz JL, et al. (2013) Pre-Operative and Early Post-Operative Factors Associated with Surgical Site Infection after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Surgical Infections 14(4): 369-373.

- Vetter D, Raptis DA, Giama M, Hosa H, Muller MK, et al. (2017) Nocito, A.; Schiesser, M.; Moos, R.; Bueter, M., Planned secondary wound closure at the circular stapler insertion site after laparoscopic gastric bypass reduces postoperative morbidity, costs, and hospital stay. Langenbeck's archives of surgery 402(8): 1255-1262.

- Silva AFd (2023) Risk factors for the development of surgical site infection in bariatric surgery: an integrative review of literature. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem.

- Guo H, Zheng T, Lin Y, Tang T, Zhang Z, et al. (2024) Real-world effectiveness of a new powered stapling system with gripping surface technology on the intraoperative clinical and economic outcomes of gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 22(1): 38.

- Fegelman E, Knippenberg S, Schwiers M, Stefanidis D, Gersin KS, et al. (2017) Evaluation of a Powered Stapler System with Gripping Surface Technology on Surgical Interventions Required During Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques Part A 27(5): 489-494.

- Wang S, Hua Y, Liu J, Huang ZF, Clymer JW, et al. (2023) A Comparison of the Preclinical Performance of the Echelon™+ Stapler with Thunderbird Reloads to Two Commercial Endoscopic Surgical Staplers. Med Devices (Auckl) 16: 229-236.

- Fortin SP, Petraiuolo W, Cafri G, Scapini G, Agarwal P et al. (2022) Comparison of Clinical Outcomes of Gripping Surface Technology Staple Reloads versus Standard Staple Reloads Used with Manual Linear Surgical Staplers. Med Devices (Auckl) 15: 385-399.

- Hsiung TTH, Sambol JT, Gaarrera GV, Shakir HA (2024) Robotic-assisted thoracoscopic resection of a mature anterior mediastinal teratoma in an adult. Ann. Surg. Case Reports & Image.

- Huang ZF, Vandewalle JA, Clymer JW, Ricketts CD, Petraiuolo WJ (2022) Improving Performance and Access to Difficult-to-Reach Anatomy with a Powered Articulating Stapler. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research 15(null): 329-339.

- Sakran N, Goitein D, Raziel A, Keidar A, Beglaibter N, et al. (2013) Gastric leaks after sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter experience with 2,834 patients. Surgical endoscopy 27(1): 240-245.

- Benedix F, Poranzke O, Adolf D, Wolff S, Lippert H, et al. (2017) Staple Line Leak After Primary Sleeve Gastrectomy-Risk Factors and Mid-term Results: Do Patients Still Benefit from the Weight Loss Procedure? Obes Surg 27 (7) 1780-1788.

- Papet E, Chati R, Pinson J, Rozenbaum P, Roussel E, et al. (2025) Management of Gastric Leak after Sleeve Gastrectomy: A 13-year Experience in a Tertiary Referral Center. Obes Surg 35(5): 1672-1678.

- Gipe J AA, Nguyen SQ (2025) Managing Leaks and Fistulas After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Challenges and Solutions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 18: 1-9.

- Boeker C, Brose F, Mall M, Mall J, Reetz C, et al. (2021) A Prospective Observational Study Investigating Postoperative Hemorrhage After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy Using Bipolar Seal and Cut Caiman (Aesculap AG). International Surgery 105(1-3): 637-642.

- Aiolfi A, Gagner M, Zappa MA, Lastraioli C, Lombardo F, et al. (2022) Staple Line Reinforcement During Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes Surg 32(5): 1466-1478.

- Choi YY, Bae J, Hur K Y, Choi D, Kim YJ (2012) Reinforcing the staple line during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: does it have advantages? A meta-analysis. Obes Surg 22(8): 1206-1213.

- Jing W, Huang Y, Feng J, Li H, Yu X, et al. (2023) The clinical effectiveness of staple line reinforcement with different matrix used in surgery. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 11: 1178619.

- Rawlins L, Johnson BH, Johnston SS, Elangovanraaj N, Bhandari M, et al. (2020) Comparative Effectiveness Assessment of Two Powered Surgical Stapling Platforms in Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Retrospective Matched Study. Med Devices (Auckl) 13: 195-204.

- Tabibian N, Swehli E, Boyd A, Umbreen A, Tabibian JH (2017) Abdominal adhesions: A practical review of an often-overlooked entity. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 15: 9-13.

- Jung JJ, Park AK, Witkowski ER, Hutter MM (2022) Comparison of Short-term Safety of One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy in the United States: 341 cases from MBSAQIP-accredited Centers. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 18(3): 326-334.