Evaluation of Abdominal Pain and Fever in a Long-Term Transplant Recipient: A Report of an Unusual Case of Renal Infarction of a Failed Graft

Randall S Stafford1*, Adetokunbo Odunaiya2, Jo-Anne L Suffoletto3 and Stephan Busque4

1Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Prevention Research Centre, USA

2Stanford University School of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, USA

3Stanford University School of Medicine, Division of Primary Care and Population Health, USA

4Stanford University School of Medicine, Department of Transplant Surgery, USA

Submission:January 29, 2025;Published:February 10, 2025

*Corresponding author: Randall S Stafford, Professor of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Prevention Research Center, 3180 Porter Drive, Palo Alto, CA-94304 United States. Email: rstafford@stanford.edu

How to cite this article: R S Stafford, A Odunaiya, J-A L Suffoletto, S Busque. Evaluation of Abdominal Pain and Fever in a Long-Term Transplant Recipient: A Report of an Unusual Case of Renal Infarction of a Failed Graft. Open Access J Surg. 2025; 16(3): 555937. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2025.16.555937.

Abstract

As this rare case of acute renal infarction in a long-failed renal graft illustrates, evaluation of abdominal pain in transplant recipients requires a very broad differential diagnosis. Acute renal infarction, often due to thromboembolic events, results in tissue necrosis with varying signs and symptoms that often include local pain, fever, reduced renal function, and systemic inflammation. The 65-year-old subject of this case report is a healthy and fit recipient of two kidney transplants on long-term immunosuppressive medications. He presented with right lower quadrant abdominal pain, intermittent moderate fevers, anorexia, and malaise. Laboratory testing most prominently showed systemic inflammation with significantly elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Abdominal CT scanning showed fat stranding and small bowel obstruction. After consideration of typical surgical etiologies; viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections; autoimmune disease, and kidney rejection, he was diagnosed with an inflammatory reaction to acute infarction of his first 40-year-old non-functioning renal graft. A month-long prednisone taper, held earlier due to concerns about worsening an infectious process, produced dramatic pain relief and a reduction in systemic inflammation. The subject resumed both work and vigorous exercise with only occasional, mild right lower quadrant pain likely from continuing renal necrosis. This case emphasizes: 1) the potential longevity and quality of life possible with kidney transplant, 2) common and uncommon causes of abdominal pain that must be considered in renal transplant recipients, 3) the diverse symptoms attributable to inflammation, and 4) the unique features of renal infarction occurring in a non-functioning renal graft.

Key words: Renal Transplant, Acute Abdomen; Renal Infarction; Systemic Inflammation; Retransplantation; Failed Renal Graft

Abbreviations: Abs IG: Absolute Immature Granulocyte Count; Abs LMC: Absolute Lymphocyte Count; Abs NTC: Absolute Neutrophil Count; ALT: Alanine Transferase; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; COVID-19: Corona VIrus Disease of 2019; CT: Computed Axial Tomography; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid; EBV: Epstein-Barr Virus; EMD: Emergency Medical Department; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; HSV: Herpes Simplex Virus; HZV: Herpes Zoster Virus; Kg: Kilogram; NF: Nonfasting; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; RNA: Ribonucleic Acid; Rx: Prescription for; SII: Systemic Immune-Inflammatory Index; Sx: Symptoms; WBC: White Blood Cell Count

Introduction

A broad range of etiologies can produce fever and abdominal pain in renal transplant recipients [1]. These vary from common issues in the general population to esoteric causes that depend on carefully acquiring a complete surgical and medical history, thorough laboratory evaluation, and appropriate use of imaging technologies. Transplant recipients on immunosuppression are at increased risk for a broad range of typical and unusual infections [2,3]. Acute graft rejection and graft intolerance can also present as abdominal pain as can malignancy, toxic transplant medication effects, and gastrointestinal autoimmune disease [4]. More common surgical diagnoses include appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, and adhesive complications [5]. We review the evaluation of possible causes of abdominal pain with fever and small bowel obstruction in a previously healthy and athletic, twice transplanted recipient. After a month-long diagnostic quandary, the subject was diagnosed with a marked inflammatory reaction to subtotal infarction of his first 40-year-old renal graft that had failed in 2005.

Case Presentation

History of Present Illness: The subject, a 65 year-old man with a history of two kidney transplants presented to a local emergency department on Day 2 following 18 hours of increasing right inguinal pain accompanied by abdominal distension, reduced appetite, and intermittent fevers to 38.6°C. Prior to symptom onset, he reported a three-week period of grant proposal preparation with limited sleep, poor diet, and minimal physical activity. At presentation and throughout his course, he experienced minimal nausea and occasional soft bowel movements without diarrhea or blood with no vomiting, shortness of breath, chest pain, palpitations, or dysuria. His initial exam included temperature 37.3°C, blood pressure 156/82 mm, heart rate 85 beats per minute. He had abdominal guarding, point tenderness in the right inguinal area without radiation, and hypoactive bowel sounds with no inguinal hernias. His lungs were clear with regular heart sounds without murmurs, and normal skin, neurological, and psychological findings.

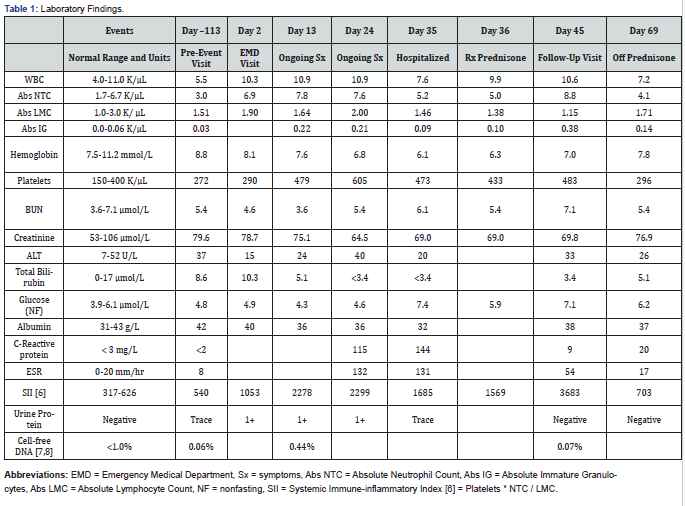

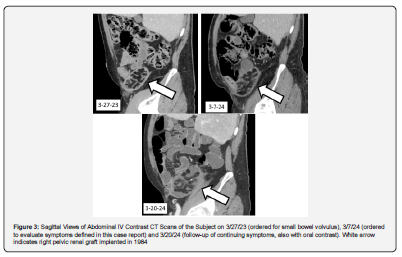

Emergency department laboratory findings included a creatinine of 78.7 μmol/L, a WBC of 10.3 K/μL with 68% neutrophils, lactate of 0.8 mmol/L, lipase of 11 U/L, COVID-19 PCR negative, and normal electrolytes and liver function tests (Table 1). An abdominal CT scan with IV contrast showed a non-functioning right pelvic renal graft with swirling of mesenteric fat and small, local pericolonic ascites (Figure 1-3). Nearby distended loops of ileum showed fecalization consistent with partial small bowel obstruction. He had a functioning and well-perfused left pelvic renal graft. His appendix was normal. Compared to a scan 12 months earlier, the fat stranding and signs of obstruction were new.

Past medical history

The subject was diagnosed in 1982 with end-stage renal disease secondary to a congenitally dysplastic small, solitary kidney. He was treated with hemodialysis in 1982-83 and a right retroperitoneal renal transplant in 1984 from his younger brother. A post-operative lymphocele around the graft necessitated re-operation with creation of a peritoneal window. This graft functioned for more than 21 years, until 2005. A second, spousal transplant was implanted retroperitoneally in the left pelvis in 2005. In 2023, he presented with volvulus and small bowel obstruction and underwent exploratory laparotomy with lysis of an adhesive band causing an internal hernia, but with no resection, followed by rapid post-operative recovery. Other history includes hypertension, iron deficiency anemia, peripheral neuropathy of unknown origin but possibly medication-related, intermittent depression, episodes of cervical radiculopathy and sciatica, and infrequently recurrent flank thrombophlebitis with borderline Protein S deficiency. Past osteonecrosis and osteoporosis resolved with cessation of chronic corticosteroids in 2006. He works as a physician and professor of medicine, exercises at high intensity, eats an ovo-lacto vegetarian diet, consumes 1-2 alcoholic drinks per week, and has never smoked. He travelled for work to Nepal and Bangladesh for two weeks returning three weeks before symptom onset. He denied any sickness during his travels or recent sick contacts. Chronic medications included sirolimus, azathioprine, lisinopril, chlorthalidone, lovastatin, duloxetine, and low-dose aspirin.

Course of illness

With modest reduction in pain after 6 hours in the emergency department, the subject returned home with instructions to follow a liquid diet escalating to a low fiber diet as tolerated. From Day 3 to Day 15, his gastrointestinal symptoms diminished, although he experienced 4 kg weight loss. He continued to experience significant inguinal pain, reduced appetite, and daily intermittent fevers to 38.6°C with fever-concurrent myalgia and malaise. He also reported worsening nocturia and urinary frequency. His exam showed temperature 37.5°C, blood pressure 104/59 mm, heart rate 91 beats per minute, and a soft abdomen with continued mild distension and diminished bowel sounds with unchanging right inguinal tenderness. There was no left abdominal tenderness. Laboratory findings from Days 3-15 included elevated markers of inflammation [6], creatinine of 75.1 μmol/L, multiple negative blood cultures, benign urinalysis, and negative stool PCR for gastrointestinal bacterial and protozoal pathogens (Table 1). Ordered to evaluate organ rejection, serum donor-derived, cell-free DNA (Allo Sure, Dx Care, Inc., Brisbane CA) was far higher (0.44%) than a previous assay (0.06%) [7,8]. A repeat abdominal CT scan on day 15 showed resolution of obstruction of the ileum but with abnormal small bowel angulation in the right lower quadrant related to inflammation around and substantial edema within the non-functioning renal allograft (Figure 1-3).

His course was unchanged on Days 15 through 36 with continued inguinal pain and intermittent fevers to 37.5°C. With concern for possible Salmonella infection, azithromycin 1000 mg per day was prescribed, but discontinued after 3 days after no symptomatic change and additional negative blood culture results. Notable Day 15-36 laboratory findings (Table 1) included continued elevated markers of inflammation, a reduced creatinine level of 64.5 μmol/L, negative serum PCR for EBV, HSV, HZV, and CMV, and a negative donor-specific antibody screen against his functioning allograft. Serum bacterial screening indicated no bacterial ribosomal RNA detected via PCR. From Days 30-35, azathioprine was held, with an increase in abdominal symptoms.

On Day 35, the discouraged subject was admitted to the hospital to overcome scheduling problems and facilitate a more intensive work-up and potential renal biopsy and/or abdominal surgery. Exam was unchanged with temperature 37.2°C, blood pressure 121/81 mm, heart rate 95 beats per minute. Chest x-ray was clear. Renal ultrasound with Doppler of the non-functioning right kidney showed low-level blood flow with preserved brisk upstrokes in the inferior segmental artery but absent wave forms in the superior and mid-segmental arteries consistent with partial renal infarction. Ultrasound of the left pelvic kidney confirmed good vascular function and the absence of hydronephrosis.

The subject was diagnosed with partial right kidney infarction likely from vascular causes. On Day 36, azathioprine was restarted as was aspirin, which had been held on admission. In addition, a prednisone pulse and 30-day taper starting at 40 mg per day was initiated for the purpose of slowing renal necrosis and blunting his immune response. The patient adhered well to this regimen despite initial hypomanic symptoms. Before and after hospital discharge on Day 37, substantial improvement was observed with diminished then resolved right inguinal pain and lack of fevers with improved mood and appetite. Follow-up lab testing showed an AlloSure cell-free donor DNA of 0.07% on Day 45, as well as reduced inflammatory markers, improved anemia, and a baseline creatinine of 76.9 μmol/L on Day 69 (Table 1). At five weeks post-hospitalization, the subject had only intermittent mild discomfort, was off prednisone, and had resumed work and vigorous hiking. It is likely that low level discomfort will persist while renal necrosis continues.

Discussion

This case illustrates the broad differential required in evaluating abdominal pain with fever in a transplant recipient and the likelihood of delayed diagnosis1 The subject underwent extensive work-up for viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infectious diseases, including travel-related infection. He was also assessed for potential graft rejection and adhesive complications, before treatment was undertaken for partial renal infarction diagnosed by ultrasound. Renal infarction occurs rarely, usually in patients at higher risk of arterial embolization such as atrial fibrillation or at higher risk of local thrombosis such as COVID-19 [9-13]. This subject lacked prominent risk factors for renal infarction.

This unusual case demonstrates the dramatic effect of systemic inflammation from ongoing renal necrosis and the subject’s immune reactivity despite immunosuppression. Systemic inflammatory effects included malaise, anorexia, worsening prostatic hyperplasia symptoms, and anemia, and increased renal blood flow leading to lower creatinine levels. All of these signs and symptoms were reversed with a 30-day corticosteroid pulse and taper. Steroids were considered earlier but were not given because of concerns that potential infection might be exacerbated by corticosteroids.

While a non-functioning graft may not contribute to renal function, it is alive in low blood-flow “hibernation,” still vulnerable to injury and necrosis. Debate continues regarding the options of failed graft nephrectomy, arterial embolization, or leaving the failed graft in situ [14-16]. This unusual complication was disconcerting to the subject and his donor-brother; both had psychologically endured the loss of the graft 18 years earlier.

Conclusion

The athletic, professor-subject’s 42-year history of end-stage chronic kidney disease treated with two living renal transplants demonstrates the potential longevity and quality of life associated with kidney transplantation [17,18]. Long-term survival with re-transplantation also adds considerable complexity to clinical decision-making. In evaluating abdominal pain in patients with more than one kidney transplant clinicians should consider pathology of a failed graft in their broad differential diagnosis.

Patient perspective

My two kidney transplants have allowed me to live a quality and quantity of life impossible to imagine while undergoing hemodialysis 42 years ago following the discovery of my kidney failure. I have benefitted enormously from the skills and empathy of many health professionals and the kind generosity of two living kidney donors. I have done my best to safeguard my two kidneys through vigorous physical activity, a healthy diet, and other positive health behaviors. Episodes like this sudden, unexpected illness have occurred only intermittently but are a real part of my transplant journey.

I am thankful for the diligent attention needed to diagnose the infarction of my brother’s non-functioning transplanted kidney. During this episode of illness, I was baffled and perturbed by the many signs and symptoms attributable to systemic inflammation, including fatigue, depressive symptoms, prostate symptoms, flu-like head and muscle aches, lack of interest in food, and a paradoxically reduced creatinine level. This case also illustrates several weaknesses of American healthcare. My initial emergency care was compromised by my CT scan being misread by a remote, for-profit, after-hours radiology service. Subsequent work-up proceeded slowly, in part because of difficulty scheduling specialist care and key diagnostic studies. Specialist input was not well coordinated until I was hospitalized a month after symptom onset. I have fully recovered, but this episode left my caregivers and I better prepared to anticipate the unexpected.

Author Contributions

Randall S. Stafford, MD, PhD was the subject of the case report. He also participated in the writing of the paper and conducted the literature review.

Adetokunbo Odunaiya, MD, MPH, was the subject’s transplant nephrologist during his illness and participated in the writing of the paper.

Jo-Anne L. Suffoletto, MD, was the subject’s primary care physician during his illness. She participated in the writing of the paper and independently verified the clinical and diagnostic data presented.

Stephan Busque, MD, was the subject’s transplant surgery consultant and participated in the writing of the paper.

Ethics Statement

The authors have adhered to appropriate ethical standards. The information obtained for this report were exempt from Human Subjects review. The subject of this case report has consented to the release of data.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Source of Funding

No external funding was used for completion of this case report. The authors conducted this research as part of their employment with Stanford University, which was not involved in writing, editing, approval, or decision to publish.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Wolfe C, McCoin N (2021) Abdominal Pain in the Immunocompromised Patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am 39(4): 807-820.

- Roberts MB, Fishman JA (2021) Immunosuppressive Agents and Infectious Risk in Transplantation: Managing the "Net State of Immunosuppression". Clin Infect Dis 73(7): e1302-e1317.

- Brás AC, Querido S, Mascarenhas A, Mendes R, Verissimo R, et al. (2024) Epstein-Barr virus associated colitis in kidney transplant patients: a case series. Infect Dis (Lond) 56(5): 410-415.

- Collini A, Ongaro A, Favi E, Lazzi S, Micheletti G, et al. (2024) Tacrolimus-Associated Terminal Ileitis After Kidney Transplantation, Mimicking Crohn Disease: A Case Report. Transplant Proc 56(2): 459-462.

- Yu Z, Ong F, Kanagarajah V (2023) Unique cases of large and small bowel obstruction in intraperitoneal renal transplantations: a case series and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep 2023(11): rjad640.

- Ma J, Li K (2023) Systemic immune-inflammation index is associated with coronary heart disease: a cross-sectional study of NHANES 2009-2018. Front Cardiovasc Med 10: 1199433.

- Edwards RL, Menteer J, Lestz RM, Baxter-Lowe LA (2022) Cell-free DNA as a solid-organ transplant biomarker: technologies and approaches. Biomark Med 16(5): 401-415.

- Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Macech M, Kolanowska M, Krawczyk M, Nazarewski S, et al. (2023) Free-Circulating Nucleic Acids as Biomarkers in Patients After Solid Organ Transplantation. Ann Transplant 28: e939750.

- Antopolsky M, Simanovsky N, Stalnikowicz R, Salameh S, Hiller N (2012) Renal infarction in the ED: 10-year experience and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med 30 (7): 1055-1060.

- Domanovits H, Paulis M, Nikfardjam M, Meron G, Kürkciyan I, et al. (1999) Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 78 (6): 386-394.

- Mulayamkuzhiyil Saju J, Leslie SW (2024) Renal Infarction. 2024 Mar 10. In: Stat Pearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls PMID: 35881744.

- Tsai SF (2014) The first case of atrial fibrillation-related graft kidney infarction following acute pyelonephritis. Intern Med 53(7): 763-766.

- Post A, den Deurwaarder ESG, Bakker SJL, de Haas RJ, van Meurs M, et al. (2020) Kidney Infarction in Patients With COVID-19. Am J Kidney Dis 76(3): 431-435.

- Ehrsam J, Rössler F, Horisberger K, Hübel K, Nilsson J, et al. (2022) Kidney retransplantation after graft failure: variables influencing long-term survival. J Transplant 2022: 3397751.

- Gómez-Dos-Santos V, Lorca-Álvaro J, Hevia-Palacios V, Fernández-Rodríguez AM, Diez-Nicolás V, et al. (2020) The Failing Kidney Transplant Allograft. Transplant Nephrectomy: Current State-of-the-Art. Curr Urol Rep 21(1): 4.

- Wang K, Xu X, Fan M, Qianfeng Z (2016) Allograft nephrectomy vs. no-allograft nephrectomy for renal transplantation: a meta-analysis. Clin Transplant 30(1): 33-43.

- Hariharan S, Rogers N, Naesens M, Pestana JM, Ferreira GF, et al. (2024) Long-term Kidney Transplant Survival Across the Globe. Transplantation 108(9): e254-e263.

- Braun WE, Herlitz L, Li J, Schold J, Poggio E, et al. (2021) Continuous function of 80 primary renal allografts for 30-47 years with maintenance prednisone and azathioprine/mycophenolate mofetil therapy: A clinical mosaic of long-term successes. Clin Transplant 35(1): e14131.