Unusual Case of Large Biliary Cystadenoma in a Two-Year Old Child-Diagnostics and Therapy

Firdus A1, Karavdić K1*, Begić S1, Halilović E2, Begić N3, Mišanović V3, Redžepagić J4, Bukvić M5, Džanaović A5 and Bečić E6

1Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

2Clinic for Abdominal Surgery, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

3Pediatric Clinic, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

4Institute for Pathology, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

5Institute for Radiology, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

6Clinic for Anesthesiology and Reanimatology, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Submission: October 24, 2024; Published: November 11, 2024

*Corresponding author: Karavdić K, Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinical Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

How to cite this article: Firdus A, Karavdić K, Begić S, Halilović E, Begić N, et al . Unusual Case of Large Biliary Cystadenoma in a Two-Year Old Child-Diagnostics and Therapy. Open Access J Surg. 2024; 16(2): 555931. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2024.16.555931.

Abstract

Biliary cystadenoma, a rare potentially malignant hepatic cystic lesion,is characterized by multiloculations and septations. It is common in middle-aged females (about 5% of nonparasitic liver cysts); only 12 cases are described in children. We report a rare case of hepatic biliary cystadenoma in a 3-year-old girl, with a gradually increasing in the formation in the right upper abdomen. Complete excision with a healthy liver margin was done.

Keywords: Biliary Cystadenoma; Hepatic Mass; Mucinous Cystadenoma

Introduction

Pediatric abdominal masses are relatively commonly encountered in the pediatric population, with a broad differential diagnosis that encompasses benign and malignant entities. A cyst is a closed cavity or sac with liquid or semisolid contents and an epithelial lining. Fluid-filled masses that lack an epithelial lining are called cyst-like. Childhood cystic and cyst-like abdominal masses can be difficult to characterize when they are very large and fill most of the abdomen. Because they distort normal anatomy, their site of origin can sometimes be chalenging to find. Careful evaluation of the epicenter of the mass, sites of attachment, and tissue characteristics, along with the age of the patient and clinical parameters is neccessary to evaluate these changes [1]. Abdominal cystic lesions in children may originate from parenchymatous organs or from nonparencyhmatous structures. Although these lesions have well-described imaging features, proper diagnosis usually depends on the accurate determination of the origin of the lesion. Because large lesions may resemble each other it is difficult to identify the site of origin, which results in a diagnostic dilemma [2].

Case Report

We are presenting a case report of male child, 2 years and 7 months old, with normal perinatal and antenatal development.This was the patient’s first admission to the Pediatric Clinic after referral from General Hospital Travnik. The patient was admitted with the following diagnoses: Cystic anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract (in observation), Bilateral cervical lymphadenitis, Maculopapular exanthema. Information was provided by the mother and extracted from the discharge summary from Travnik General Hospital. In medical history mother reported that three days prior to admission, the child had a fever, experienced slightly watery stools, and had a nausea, although vomiting did not occur. They visited the local health care center where an abdominal ultrasound was performed, revealing a cystic formation. Subsequently, they were referred to the department of Pediatric Gastroenterohepatology on Pediatric Clinic, Sarajevo. The child had no significant past illnesses. Regular vaccinations were administered. There were no known allergies to food or medication. Family history was unremarkable considering this pathology.

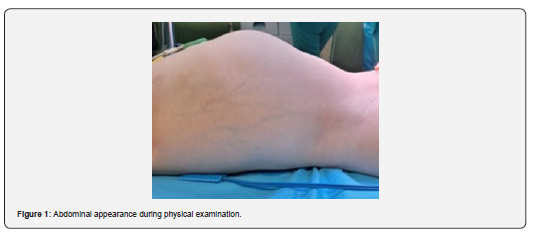

Physical examination revealed a 2-year-old male child, weighing 15.5kg and 97cm tall, was conscious, afebrile, well-hydrated, and independently mobile. The child had skin - maculopapular rash that faded on pressure. The skeletal system showed no deformities, and the head and neck had normal configuration and mobility. Neurological examination revealed no deficits. The abdomen was slightly distended but soft and non-tender. Abdominal wall deformity is verified by inspection.(Figure 1)

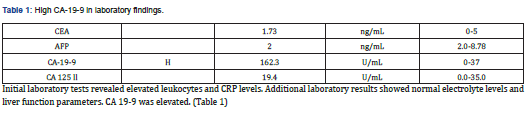

Extremities were normal in structure with full mobility, and genitalia were normal for a male child. Ultrasound finding showed that there wasn't dilatation of the bile ducts, the gallbladder was not visualized with certainty, and in the expected projection, the structure was seen that could be a part of the change itself separated by a septum, a cystic zone that imitates the appearance of a gallbladder and is filled with denser contents. Differential diagnosis was described as mesenteric, duplication cyst, cystic lymphangioma or some other change. The CT findings indicate the existence of a complex expansive cystic lesion that compresses and dislocates the surrounding organs and was located under the lower surface of the liver. There was no impression of infiltration of the surrounding structures. Differential diagnosis was described in terms that it could be mesenteric cyst, duplication cyst, biliary cystadenoma or other etiology. (Figure 2,3)

Initial laboratory tests revealed elevated leukocytes and CRP levels. Additional laboratory results showed normal electrolyte levels and liver function parameters. CA 19-9 was elevated. (Table 1)

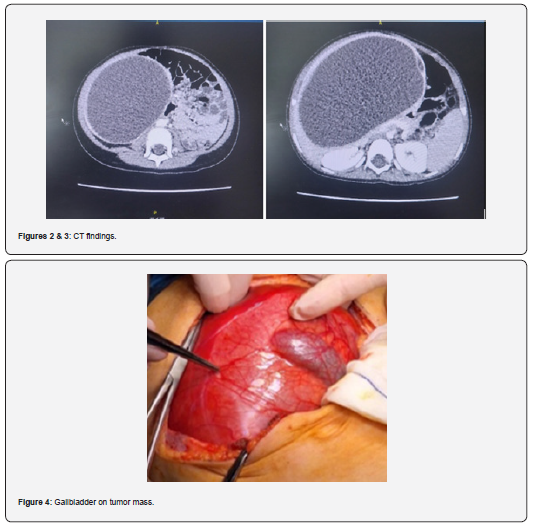

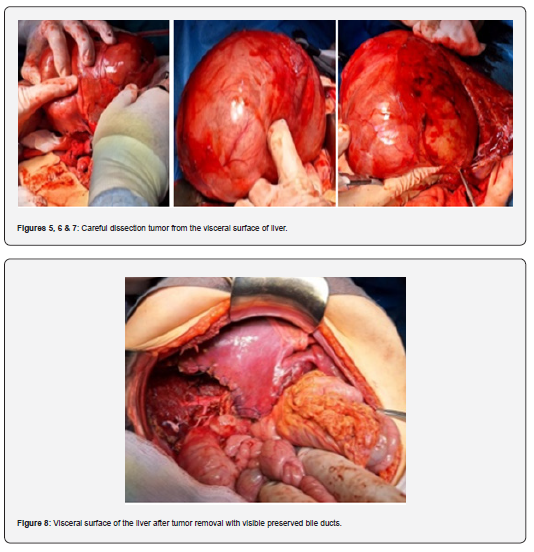

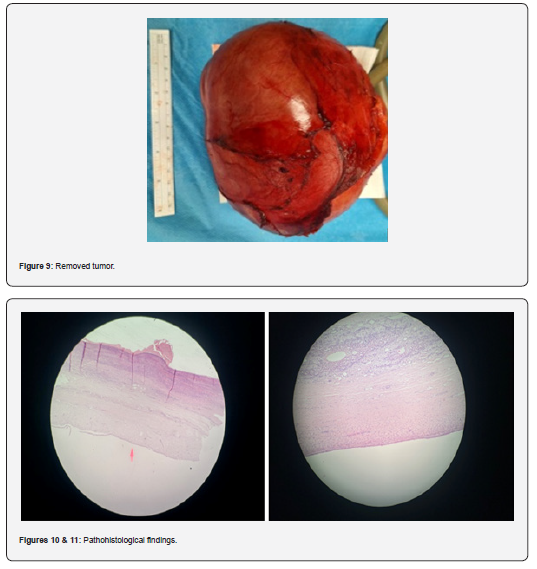

The child went to Pediatric Surgeon Consultation and it was decided that the surgery is necessary. Surgical intervention was performed . The front abdominal wall was opened (supraumbilical laparotomy). It was seen that tumor was filled with fluid. The tumorous mass was separated from the liver parenchyme. Gallblader was also separated completely from the wall of tumorous change. After carefull preparation tumor was completely excised. Cholecystectomy was done after binding of cystic duct. (Figures 4-8). The tumor was excised and sent for histopathological analysis. (Figure 9)

After the operation, the child was intubated and monitored in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). The postoperative course was uneventfull. The therapy was administered as followed: Glucosaline I+10ml 7.4% KCL at 55 ml/h, with adjustments as enteral intake improved; Cefazolin 3x350mg i.v., Amikacin 2x120mg i.v., Controloc 2x15mg i.v., Silimarin drops 3x5 drops for 2 weeks along with other supportive therapy. Regular monitoring included laboratory tests, ultrasound of the abdomen, and consultations with gastroenterologists.The child was discharged in good general condition with specific instructions for home care that involved ensuring rest and avoiding strenuous activities for one month, keeping a sterile dressing on the surgical wound, continuing Silimarin drops 3x5 drops for the next month and recommendation of follow-up with the gastroenterologist in one month with control lab results and an abdominal ultrasound.

Patohistology report showed microscopically, samples of the wall of cystic changes that are lined with partially cubical and partially cylindrical epithelium towards the lumen, whose nuclei are monotonous, with loose chromatin, without prominent nucleoli, without mitotic activity. In several foci, the cyst is deepithelialized. Subepithelially, a looser, fibromyxoid stroma is seen, less cellular, with numerous multiplied thin-walled blood vessels and multiplied lymphatic vessels. Also, individual inflammatory cells of the type of neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes, which enter the superficial epithelium, were present. In one of the sections, the subepithelial stroma appears thicker. The underlying tissue of the cyst is the liver, which has a regular histological appearance for its age. Immunohistochemically described epithelial cells lining the cyst are: CK19(+), EMA(+), WT1(-), CK7(+), CDX2(-), Podoplanin(-), CD10(-), CEA(-). OPINION/Large cystic change that is the histological characteristic of biliary cystadenoma, which is a benign tumor and a rare tumor in childhood. The change has been removed in its entirety. (Figure 9-11)

Discussion

Benign intra-abdominal cystic masses in infancy and childhood are uncommon and their etiopathogenesis, histology, localization and clinical presentation differ significantly; this could generate diagnostic dilemmas and consequent therapeutic delay in some of the cases. As cystic mass we considered a newlyformed closed cavity with liquid or semisolid contents and an epithelial lining, while fluid-filled masses that lack an epithelial lining were reffered to as cyst-like.[3] Biliary cystadenoma is a slow-growing benign lesion. That is the reason why it often presents late considering symptoms.[4] It is common in middle-aged females.[5]

Only few pediatric cases are reported so far, the smallest being an 8-month-old girl.[6] However, lately, there is a rise in pediatric cases possibly due to the improvement in imaging and diagnostics generally. The exact pathogenesis is unknown; however, hormonal influence, congenital biliary tract anomalies, and aberrant growth of hepatobiliary progenitors are some of the possibilities. The gold-standard treatment is a complete excision with clear margins due to the risk of recurrence and later malignant transformation. The rate of malignant transformation in adults is 20%, although not described in children so far.[5] The tumour is detected in the majority of patients during workup for nonspecific abdominal complaints such as abdominal discomfort, pain, and swelling. Because hepatic mucinous cystadenomas appear on preoperative imaging to be similar to a range of cystic lesions of the liver, definitive diagnosis and identification of benign and malignant cystadenomas always necessitate histological study after formal resection. [6,7] Most patients with byliary cystadenoma have normal laboratory results, while serum bilirubin and liver enzyme levels may occasionally be slightly increased although in our patient that was not the case. In asymptomatic patients, the greater use of abdominal imaging in clinical practice has led to an increase in the identification of hepatic cysts. [8] CA 19-9 is produced by ductal cells in the pancreas, biliary system, and epithelial cells in the stomach, colon, uterus, and salivary glands. While its key implication is in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), CA 19-9 is also overexpressed in a wide gamut of benign and malignant, gastrointestinal, and extra-gastrointestinal diseases. Benign conditions include pancreatitis, pancreatic cysts, diabetes mellitus (DM), liver fibrosis, benign cholestatic diseases, and other urological, pulmonary, and gynecological diseases. [9,10]

In this case, high CA 19-9 indicated that the change is probably biliary cystadenoma due to showings on radiological imaging techniques. Pediatric surgical treatment (total excision) is neccessary in most of the cases, although the evacuation of cyst content with a needle can be indicated as a first step in certain cases with the goal to decrease the size before the surgery (if the procedure is considered safe in specific patient). Biliary cystadenomas are anechoic on ultrasonography, with thicker irregular walls and internal septations. On CT, they appear as a multiseptated cystic mass with an enhanced wall. The radiologic distinction of cystadenoma from cystadenocarcinoma is still difficult.[9] Biliary cystadenoma has a favourable prognosis if it is completely succesfully resected. Recurrence is usually associated with incomplete therapeutic options such as aspiration, percutaneous drainage, ablation, marsupialization, and internal drainage. [11]

Conclusion

Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to large abdominal tumors in children should be based on anamnesis, clinical presentation, various laboratory and radiological findings. Multidisciplinary approach is very important due to wide diferential diagnosis and quite rare incidence with up to date literature consultation. Pediatric surgical treatment (total excision) is neccessary due to compressive effect of large tumor and potential for malignant alteration.Quick surgical intervention, regardless of the yet uncertain diagnosis, can lead to a complete recovery of the child, as in this case. Post-resection periodic follow using ultrasound or CT-scan and tumour markers is neccessary in cases of this diagnosis.

References

- Wootton-Gorges SL, Thomas KB, Harned RK, Wu SR, Stein-Wexler R, et al. (2005) Giant cystic abdominal masses in children. Pediatr Radiol 35(12): 1277-1288.

- Esen K, Özgür A, Karaman Y, Taşkınlar H, Duce MN, et al. (2014) Abdominal nonparenchymatous cystic lesions and their mimics in children. Jpn J Radiol 32(11): 623-629.

- Ferrero L, Guanà R, Carbonaro G, Cortese MG, Lonati L, et al. (2017) Cystic intra-abdominal masses in children. Pediatr Rep 9(3): 7284.

- Ahmad S, Sahoo SK, Manekar AA, Narahari J, Tripathy BB, et al. (2023) Biliary Cystadenoma in a Child: A Rare Entity. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 28(6): 532-536.

- Soares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Anders R, Adams RB, et al. (2014) Cystic neoplasms of the liver: Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma J Am Coll Surg 218(1): 119-128

- Bezabih YS, Tessema WA, Getu ME (2021) Giant biliary mucinous cystadenoma mimicking mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver in a child: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 88: 106523.

- Del Poggio P, Buonocore M (2008) Cystic tumors of the liver: a practical approach. World J. Gastroenterol 14(23): 3616-3620.

- Kim SH, Kim WS, Cheon JE, Yoon HK, Kang GH, et al. (2007) Radiological spectrum of hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma in children. Korean J Radiol 8(6): 498-505.

- Tran S, Berman L, Wadhwani NR, Browne M (2013) Hepatobiliary cystadenoma: A rare pediatric tumor. Pediatr Surg Int 29(8): 841-845

- Lee T, Teng TZJ, Shelat VG (2020) Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 - tumor marker: Past, present, and future. World J Gastrointest Surg 12(12): 468-490.

- Zhang FB, Zhang AM, Zhang ZB, Huang X, Wang XT, et al. (2014) Preoperative differential diagnosis between intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: a single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol 20(35): 12595-12601.