A Rare Cancer with a Rare Occurrence: Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma with Enteric Differentiation as a Cause of SVC Syndrome

Chandrasekaran K1, Lati Z1, Kalsi A1, Dave N1 and Peterson SJ1,2*

1Department of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, USA

2Weill Cornell Medical College, USA

Submission:January 09, 2020; Published: January 27, 2020

*Corresponding author:Peterson SJ, Department of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, New York, USA

How to cite this article:Chandrasekaran K, Lati Z, Kalsi A, Dave N,Peterson SJ. A Rare Cancer with a Rare Occurrence: Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma with Enteric Differentiation as a Cause of SVC Syndrome. Open Access J Surg. 2020; 11(3): 555813. DOI:10.19080/OAJS.2020.11.555813.

Keywords:Superior vena cava syndrome; Colon cancer; Rectal cancer; Adenocarcinoma; Colostomy; Immunotherapy.

Presentation

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome, also known as SVC syndrome, is an uncommon occurrence resulting from reduced blood flow to the right atrium from SVC obstruction. Patients experience multiple nonspecific symptoms such as headache, facial redness/swelling and shortness of breath. This was first noted in 1757 by the Scottish anatomist and physician William Hunter, where he recognized syphilitic aortic aneurysm as a cause [1]. Subsequently in the mid-1900s, a review done on 274 cases of SVC syndrome suggested 40% of these cases were due to infections (tuberculous mediastinitis and syphilitic aneurysms) [2].

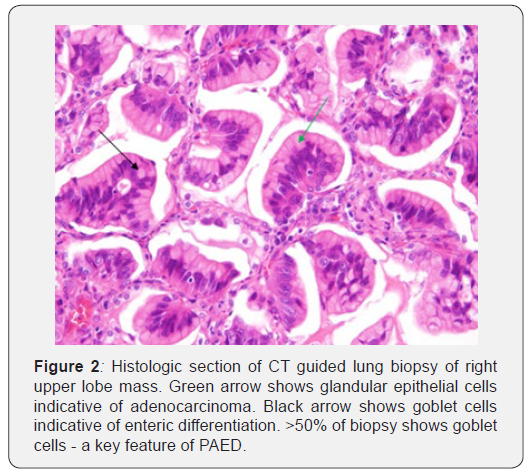

In more recent times, a significant majority (60-90%) can be attributed to lung cancers alone, however, we now see the rise of benign causes of this syndrome from intravascular devices and pacemakers (some studies reporting up to 40% of cases) [1,3-7]. Metastatic disease-causing SVC syndrome has been shown to be relatively infrequent, accounting for under 10% [8]. Here we show a patient who developed SVC syndrome from an extremely rare malignancy, pulmonary adenocarcinoma with enteric differentiation (PAED). PAED is a subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma in which the enteric component exceeds 50%. To differentiate the primary cancer in this subtype, immunohistochemistry with markers such as CK-7, CK-20, CDX-2 and TTF-1 are used. However, in those who are CK-7 negative, differentiation becomes difficult and clinicians must base their assessment on imaging/endoscopic findings. Here we present the 4th case in English literature of CK-7 negative PAED, but the first described case of PAED associated with SVC syndrome.

Assessment

Patient was a 69-year-old male with a known history of stage IV prostate cancer diagnosed in 2012 that was treated with leuprolide. He was asymptomatic until 2018 where he was found to have an elevated PSA with new back pain. A CT scan showed multiple large lung masses, one of which appeared to be related to the pleura of the right lung. Bone scan was evident for multiple bone and soft tissue metastases. Given the rare propensity of prostate cancer to metastasize to the lungs, he was referred for a CT guided lung biopsy.

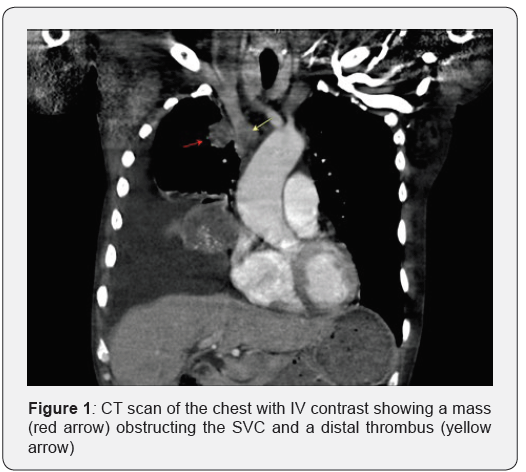

Prior to the biopsy the patient presented to the ED with dizziness and facial swelling for two weeks. He was hypotensive, tachycardic, and tachypneic with a large right pleural effusion on chest x ray. CT scan of the chest showed a lung mass partially compressing the superior vena cava at the area of its junction with the innominate vein with evidence of thrombosis distally (Figure 1). Therapeutic thoracentesis was performed alleviating the patient’s symptoms.

CT guided lung biopsy was then done, and results were supportive of enteric/intestinal-type adenocarcinoma (cytokeratin 7 -, cytokeratin 20 +, and CDX 2 +) (Figure 2 will be pathology of lung mass). Patient at this time had no known history or suspicion of an enteric malignancy.

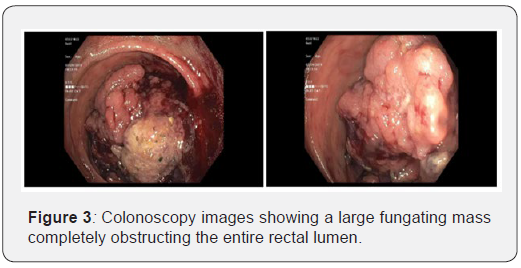

His recovery course was then complicated by hematochezia. Colonoscopy was evident for a large fungating mass that was obstructing the entire rectal lumen (Figure 3). Biopsy showed a tubular adenoma with high grade dysplasia. Colo-Rectal Surgery then performed a transverse loop colostomy to relieve the obstruction.

Management

The primary origin of metastatic adenocarcinomas can be difficult to diagnose. The use of immunostaining over the past several years has greatly increased our ability to make an accurate diagnosis. Staining with antibodies to CDX-2, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, and thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1) have all proven to be useful [1]. These help to differentiate between primary lung cancer, metastatic lung cancer and colorectal adenocarcinomas.

CDX-2 is a protein found in transcription factors on intestinal epithelial cells. Cytokeratin 20 (CK-20) is a major cellular protein found in mature enterocytes and Cytokeratin 7 (CK-7) is a protein found in glandular epithelial cells of the breast and lungs. This patient’s biopsy stained CK 20 +, CDX2 + and CK 7 -. This is indicative of an enteric malignancy.

The patient experienced a rather complicated disease course. Initially it was presumed he had a recurrence of his prostate adenocarcinoma with metastases. However, prior to his lung biopsy, he presented with SVC syndrome. Later the same admission, he developed hematochezia where a colonoscopy showed a large fungating mass obstructing the entire rectal lumen. The biopsy and immunohistochemical stains (of the lung and rectal mass) were consistent with rectal adenocarcinoma. He underwent a diverting loop colostomy, radiation to his rectal mass and was placed on chemotherapy with bevacizumab/irinotecan. Bevacizumab, an angiogenesis inhibitor, and irinotecan, an inhibitor of DNA replication, is a widely used chemotherapy regimen in metastatic colorectal cancer.

At the time of diagnosis, around 50% of patients with colorectal malignancies will have metastases or non-operable disease [9]. Those with unresectable disease, such as this patient, have a 5% or less 5-year survival rate [10]. In metastatic colo-rectal cancer, combination chemotherapy is now the standard of care in those with good functional status (ECOG 0-1). Overall survival rates in these patients can be up to 30 months (median) [11].

Authorship

All authors had access to manuscript and a role in writing it.

References

- Hunter W (1757) The history of an aneurysm of the aorta with some remarks on aneurysms in general. Med Obs Enq 1: 323-357.

- Schechter MM (1954) The superior vena cava syndrome. Am J Med Sci 227(1): 46-56.

- Flounders JA (2003) Oncology emergency modules: superior vena cava syndrome. Oncol Nurs Forum 30(4): E84-E90.

- Ahmann FR (1984) A reassessment of the clinical implications of the superior vena caval syndrome. J Clin Oncol 2(8): 961-969.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW (2006) The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine 85(1): 37-42.

- De Potter B, Huyskens J, Hiddinga B, Spinhoven M, Janssens A, et al. (2018) Imaging of urgencies and emergencies in the lung cancer patient. Insights Imaging 9(4): 463-476.

- Friedman T, Quencer KB, Kishore SA, Winokur RS, Madoff DC (2017) Malignant Venous Obstruction: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome and Beyond. Semin Intervent Radiol 34(4): 398-408.

- Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J (2007) Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med 356: 1862-1869.

- Piedbois P, Rougier P, Buyse M, Pignon J, Ryan L, et al. (1998) Efficacy of intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracil compared with bolus administration in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 16(1): 301-308.

- Hoff PM, Ansari R, Batist G, Cox J, Kocha W, et al. (2001) Comparison of oral capecitabine versus intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin as first-line treatment in 605 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19(8): 2282-2292.

- Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, Innocenti F, Fruth B, et al. (2017) Effect of First-Line Chemotherapy Combined With Cetuximab or Bevacizumab on Overall Survival in Patients With KRAS Wild-Type Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 317(23): 2392-2401.