Characteristics of Lactational Mastitis in Western Kordufan Region - Sudan: A Hospital Based Cross Sectional Study

Mutasim Abdallah Elobaid Makkawi*, Wlaedeen Ibraheem Ebaid Babikir and Salih Yahia Mohammed Yahia

West Kordufan University, Elnohud Teaching Hospital, Sudan

Submission: September 11, 2019; Published: October 23, 2019

*Corresponding author: Mutasim Abdallah Elobaid Makkawi, Assistant Professor of Surgery, West Kordufan University, Faculty of Medicine, Consultant General Surgeon, Elnohud Teaching Hospital, Elnohud, Sudan

How to cite this article:Mutasim Abdallah Elobaid Makkawi, Wlaedeen Ibraheem Ebaid Babikir, Salih Yahia Mohammed Yahia. Characteristics of Lactational Mastitis in Western Kordufan Region - Sudan: A Hospital Based Cross Sectional Study. Open Access J Surg. 2019; 11(1): 555805. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2019.11.555805.

Introduction

Lactational mastitis is a common inflammatory breast condition worldwide. It is defined clinically as a tender, hot, swollen, wedge shaped area of the breast that associates with systemic illness such as fever of 38.5° C or greater, chills and flulike aching. It may lead to cessation of breast feeding and accordingly it adversely impacts infant nutrition [1]. The major infectious organisms implicated as mastitis pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Hemophilus influenza [2,3]. However, mastitis may occur without involving a bacterial infection. Although many factors have been associated with lactational mastitis are identified, however, knowledge of the cause and disease process remains limited [4], moreover, some studied factors are still inconclusive. Some epidemiologic studies have been carried out to investigate the incidence and potential risk factors that could contribute to mastitis during lactation; nevertheless, a true global knowledge about mastitis has not being reached yet [5].

The most convincing and acceptable triggering factors for disease process is ineffective removal of breastmilk leading to milk stasis [4]. Adding to that; nipple trauma, prima parity, lack of support for breastfeeding, blocked ducts and previous mastitis are a known contributing factor to mastitis. Furthermore, maternal condition like maternal age, fatigue, stress and anemia also seem to be involved with lactational mastitis. Despite the observed significant burden on women in the study region, very little is documented or known about mastitis incidence, prevalence, risk factors, clinical pattern and complications there. Here we aim to identify sociodemographic characters, clinical pattern and risk factors among our study group and compare with regional and international findings in his field.

Methods

We conducted a hospital-based cross-sectional study in Elnohud teaching hospital and tow private dispensaries in Elnohud city over 12 months in 2018. Elnohud city is the biggest city in west kordufan state in Sudan. Its hospital and the 2 private dispensaries have the highest rate of patients in the state. Here we aim to identify the sociodemographic factors, clinical pattern and risk factors in our patients among whom we think these factors are different from that in the literature. 158 nursing mother who presented with symptoms related to breast were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Each case was diagnosed based on clinical presentation, laboratory investigations and imaging in form of breast ultrasound. The adopted symptoms and signs for establishing diagnosis were local symptoms and signs of mastitis like breast pain, local swelling, erythema, hotness and tenderness in the presence or absences of systemic symptoms. Data were categorized into sociodemographic information, pattern of presentation, risk factors and local developed complications. Complicated mastitis is considered when a woman developed breast abscess, ulcer with or without mammary fistula. The questioner contains questions for the risk factors which we already identify it after reviewing literature. It includes; risk factors related to feeding technique, stasis, mother, child and hygiene. The obtained data was entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Scientist (SPSS) version (22). Data summary was presented in tables, and graphs. Concerning ethical issues, approval was obtained from the ethical committee, faculty of medicine, west Kordufan University and a written informed consent was obtained from each participant after explaining the research objectives and procedures.

Results

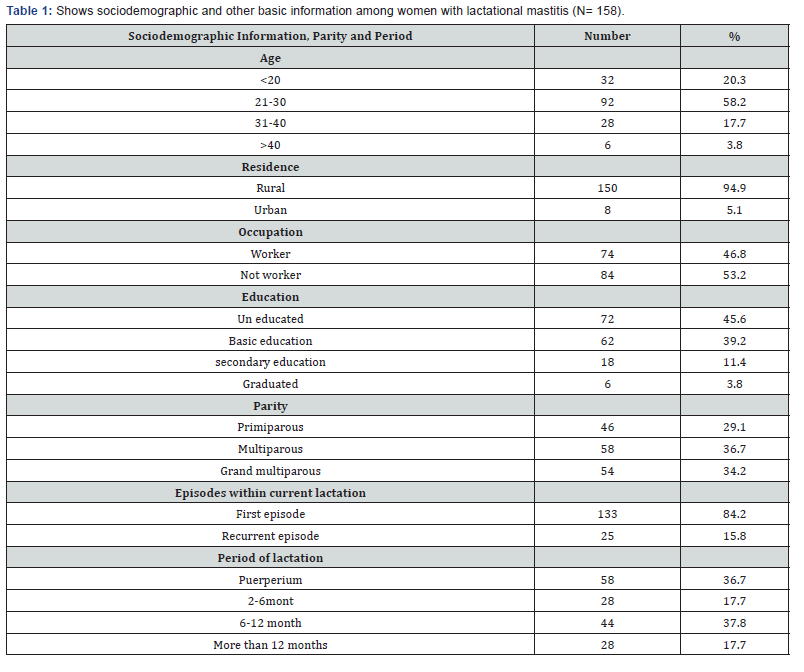

One hundred fifty-eight lactating ladies participated in this study (0.7% of total admission), (response rate is 100%). The mean age was 27.4 +/- 7.17years (range, 16 - 50 years). Greater than half (58.2%) is in age group 21-30 years. Majority of the patients live in rural areas,150 (94.9%) and near have are uneducated 72(45.6%). Also, 131(83%) has no medical insurance (Table 1). The found that, multiparous and grand multiparous ladies represent more than two thirds of the affected women. It is also found that, mastitis is more frequent in two peaks; one in puerperium 58 (36.7%) and the other in the second half of the year of lactation 44(37.8%). Twenty-five percent (15.8 %) of women reported recurrent episodes of mastitis in their current period of lactation and 20 (12.6%) patients have bilateral mastitis (Table 1).

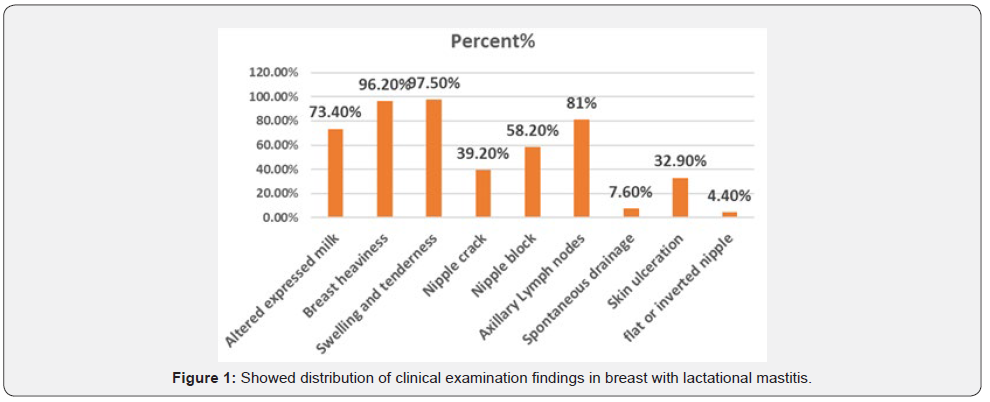

The mean duration time of symptoms in our study group is 11.8 +/-8.06 days (range 2- 30 days), Almost all patients were presented with symptoms of acute inflammation, however, clinical signs are widely variable; the vast majority have altered expressed milk in (73.4%), breast swelling and tenderness in (97.5%), breast heaviness in 152(97.3%), palpable axillary lymph nodes in (81.1%) while near halve has skin and areolar shininess in (51.8%), nipple block in (58.2%), nipple crack in (39.2%). The least examination finding was spontaneous puss drainage in (7.5%) (Figure 1).

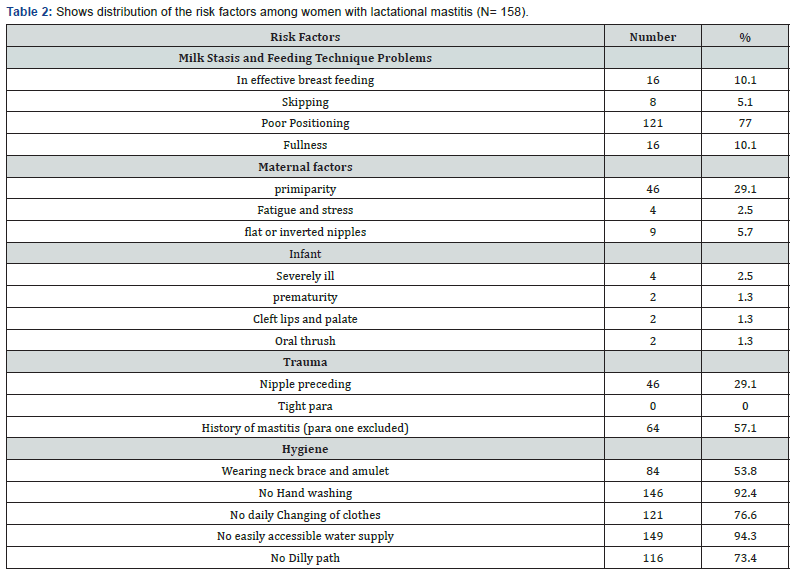

Milk stasis as a risk factor for mastitis, is found in 121(77%) and is largely correlate to poor feeding technique (positioning and nipple attachment). Other related risk factors frequency is: skipping (missed feeds) in 8(5.1%), ineffective breast feeding in 16(10.1%), and preceding fullness in16 (10.1%). Maternal related risk factors are other important found risk factor which includes (as listed in Table 2); primiparity in 46(29.1%), fatigue and stress in 4(2.5%), flat or retracted nipple in 9 (5.7%) patients. Infant related risk factors include child illness 4(2.5%), prematurity 2(1.3%), cleft lips and palate in 2(1.3%) and oral thrush in 2(1.3%) patients. Trauma like (nipple crack, ulceration, bite, others) is also a recognized risk factor for lactational mastitis in this study. it is found in 46(29.1%). Risk factors that commonly reported in some western studies like warning tight para, using antifungal creams and nipple piercing are not existing here.

History of mastitis, as a risk factor was detected in 64(40.5%) and it seems to be high. Similarly, poor hygienic practice indicators in particular, hand washing before commencing breast feeding were detected in majority of nursing mother (Table 2). It is known that, the areas where those people live are characterized by scarcity of drinking water and water for other uses, therefore, the hygiene of mothers and infant is probably poor. We also observed that a lot of infant weaning dirty neck braces and amulets and we consider it as poor hygienic indicator. We found more than half mothers wear their infants these amulets (Table 2).

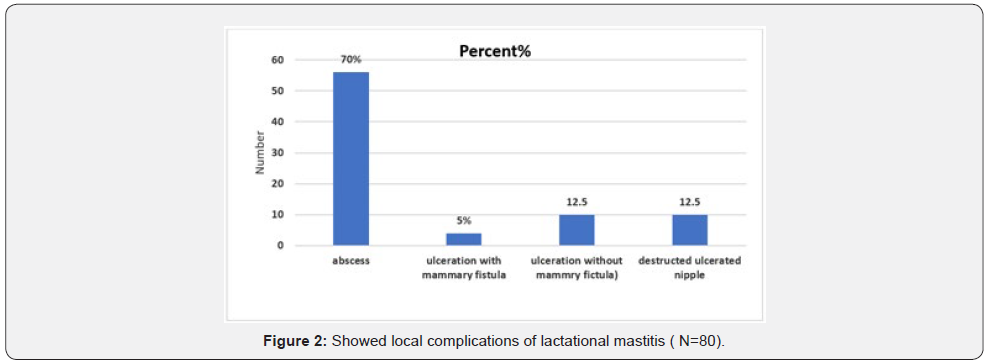

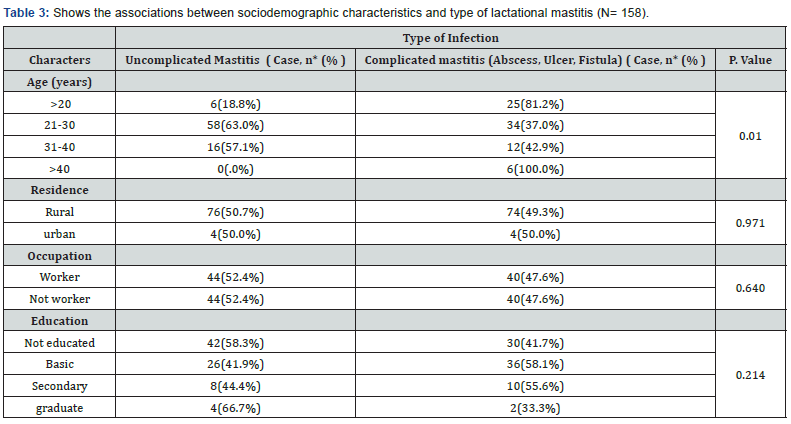

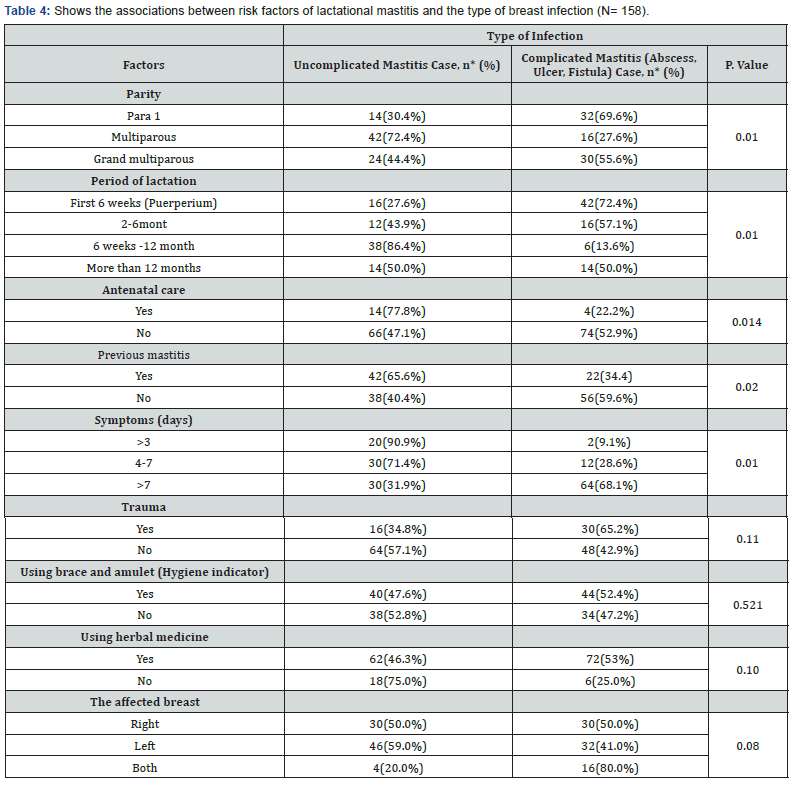

Almost half of the patients 80(50.6%) developed local complications which are categorized as follow; breast abscess in 56(35.4%), skin ulcer with mammary fistula in 4(2.5%), skin ulcer without mammary fistula in 10(6.3%) and destructed nipple in10 (6.3%) (Figures 2 & 3). On the other hand, selfcessation of breast feeding was largely temporary in 102 (64.6%) while permanent cessation occurs in 15(9.5%). In order to predict the risk of developing local breast complications, we look in to association between frequency of these complications and certain related factors to patients and mastitis; here, the age shows significant relationship with frequency of that complications; in which more complications are found at extremes of lactating women age; 75% of the teenager nursing mother and 100% of women above 40 years developed complications (P= 0.004). In contrary, there is no significant association encountered between other sociodemographic characters like (residence, occupation and educational level) and occurrence of complications (P> 0.05) (Table 3). However, the study shows that, there is significant relationship with the parity where complications are found to be more among primiparous mothers 69.6% (P= 0.004). Similarly, a more frequent complications are noted among women who lacks antenatal care (52.9%) (P= 0.014). There is also, a significant relationship between past history of mastitis and occurrence of local breast complications; more frequent complications are found to be among nursing mother who had previous mastitis (59.6%) (P= 0.02) (Table 4). Nipple injury has also significant relationship with occurrence of complications; where more frequent complications are noted among women who have preceding nipple injuries 65.2% (p = 0.11). Similarly, relationship is documented with women using herbal medicine and those who presented late with (p = 0.10) for both. The current study failed to show any significant relationships between wearing dirty brace or amulet and local breast complications (P> 0.05). Also, there is weak relationship between occurrence of complication and bilateral mastitis (P> 0.08) (Table 4).

Discussion

Lactational mastitis worth studying since approximately a quarter of mothers considered it as a reason for stopping breast feeding [6]. It alters cellular composition of milk and local defense within the breast; hence, it is a powerful risk factor promoting vertical transmission of infection. Eventually if not treated promptly, mastitis may proceed to give rise to a local abscess and sepsis. There is variable reported incidence of lactational mastitis in literature, from low as high as 33% in lactating women while others as low as 2.6% [6-17].

Although, there is no registered data about incidence and prevalence of lactational mastitis in our study area, we believe it represents a significant burden to lactating women there. Women of these areas suffer from poverty, illiteracy, and lacking support, and most of them are forced to be treated by using herbal medicine. Moreover, challenges of the low resource health system and habits of delayed presentation worsen women conditions, so affect the outcome of management. We gather information from 158 lactating women and analyzed it in order to detect any unique characteristics of this disease related to our area. We found differences in sociodemographic characteristics when compare to other studies. Our study group are younger than in many studies; the mean age which is (27.4 +/- 7.17years) here, is lower than that reported by Mediano P et al. [17] but, Viduedo AD et al. [1], Cullinane M and Frances Perry House - Amir LH et al. [18]. This probably due to early marriage age and this reflected by more than half of the study population (58.2%) are located in the age group between 21–30 years. Furthermore, teenager breast feeding mother representing 20.3% of the whole study group which is higher than that reported by Egbe TO from Cameron [19] and Foxman B et al. [9]from united states.

However, the mean age in our study a little pit similar to study by Kinlay JR et al. [20] and to randomized control trial by Amir LH in his studied group (Attachment to the Breast and Family Attitudes to Breastfeeding, ABFAB), even though, his group comprised of nulliparous ho get pregnant [21]. The reasons for younger age lactating women to be affected more with lactational mastitis here are perhaps due to lacking awareness about proper healthy breast feeding technique and all other considerations related to breast feeding practice. The striking finding in this study is that, vast majority of affected women are from rural areas and not the city, they live dozens to hundreds of miles from Elnohud city and this would probably render them far from medical services. Moreover, theses unlucky women who are field workers and lacking even education and medical insurance are restricted by poverty and believes of local rural community towards dealing with any diseases in a proper way (Table 1). Although mastitis may occur at any stage of lactation including second year, high incidence usually occurs in early lactation period [6,18]. Our finding is consistent with these studies as (54%) of mastitis cases occur in the first six months who among them, cases during puerperium represent (36.7%) of the total cases.

An old report from WHO in 2002 declared that mastitis is commonest in the second and third week postpartum, with most reports indicating that 74% to 95% of cases occur in the first 12 weeks according to series of studies [22]. In a combining study by Amir LH et al. there are (53%) episodes occurred in the first four weeks postpartum, (65%) episodes occurred in weeks five to eight and (44%) episodes in weeks nine to twelve; thus (71%) of episodes occurred in the first two months and (83%) in the first three months postpartum. This high frequency of mastitis in early lactation in relation to this study in comparison to our study perhaps due to variety in methods of recruitment of cases where it is through a 6-month telephone interview in Amir LH et al. study [18].

In contradiction to fact of increase frequency in early lactation , two studies in USA stated far lower frequency of mastitis in early lactation; one detected (9.5%) incidence in the third postpartum month while the other found slightly fewer than (10%) of American women experienced mastitis in three months postpartum in a large cohort study [9]. It is not obvious why our patients show increase frequency of mastitis in 2 peaks pattern i.e. during puerperium and between 6 to 12 months of lactation. The high frequency of nursing mothers who developed mastitis in the first 6 month of lactation in our study is a problem of concern. future work should therefore include meticulous search to detect the real predisposing factors specifically in this stage.

Many authors claim that primiparous breast feeding women are more likely to develop lactational mastitis [23], Viduedo AFS et al. [1] found 64.0% of affected women were prim parous [1]. However, our result is inconsistence with these studies where primiparous constituted only near third (29.1%) of the studied group and the majority were multiparous 70.9% (Table1). This result may be attributed to previous mastitis which is strong risk factor that responsible from increased frequency of mastitis among multiparous and multiparty is very prevalent in our study area. There is great variability in setting of the risk factors for lactational mastitis by many studies [12,20], however, some demographic and other baseline clinical characteristics besides breast feeding malpractice are widely accepted risk factors that predispose to lactational mastitis. Generally, these factors include: milk stasis, factors related to child, or mother, nipple trauma, previous history of mastitis and other factors like wearing tight para or use of antifungal nipple cream nipple, piercing and using of breast pumps [24]. However, and with regard to cultural background of our local community, none of our patient described exposure to these risk factors.

In general, the risk factors for developing mastitis are somehow different from what reported in most of studies especially from western countries. Living in rural area is by far, the most frequent determinant of lactational mastitis in this study, however, there is no certain proven explanation to question why lactational mastitis affects women from rural area more than from the city. Perhaps rural community may be characterized by presence of some factors favoring development of mastitis. In our rural areas, women get marriage earlier and keep giving child birth for the rest of their reproductive life. Teenager nursing mothers lack awareness about proper breast feeding practice, they follow advices from their mothers and grandmothers which usually inclined to using of herbal medicine instead of seeking hospital management. Furthermore, these women are living in villages where they gain water from wells, water pools and dams. therefor they find difficulty in keeping good personal hygienic.

Although hygienic practice concerning breast feeding was not tested wholly, we find some poor hygienic practice indicators to be the most prevalent one among other risk factors. we claim lacking water supply to be the basic determinant of consequent poor hygienic practice in our study group. Other striking risk factor is previous history of mastitis which is a very obvious risk factor among multiparous (57.1%), however, we don’t know whether this attack of mastitis is because pathological changes left by previous inflammation that favor development of mastitis or a woman just develop mastitis because she exposed to the same risk factors. A woman could have up to 4 times history of mastitis suggesting it as a persuasive strong risk factor. Similarly, most studies reported it as strong risk factor of mastitis [7,18].

We also observed that many infants wear contaminated neck braces and amulets (Figure 4). This dirty braces and amulets are one of hygienic indicator that we observed it early in the study. Infants usually keep liking it till it gets contaminated and very dirty and it regularly scratch the nipples during breast feeding. We believe it would be one of the postulated risk factors that need to be proved. It is obvious that ancestral and traditional breast feeding practice is the dominated one. We found that poor positioning during breast feeding is a frequent breast feeding technique in our study group and certainly this require raising awareness of breast feeding practice. There are some other reported risk factors that mentioned in many studies like wearing tight para, tattooing and nipple piercing. We did not report this in our patient only because they are not part of their social practice.

Complications rate in this study is considered to be very high (50.6%) with an abscess representing 70% of the cases. Delayed presentation and wasting time using herbal medicine are the main factors favor development of complications. In agreement with this finding, a comparable result was reported by Viduedo Ad on 114 hospitalized women where 62 (54.4%) developed complications [1], however, complication rates are widely variable and most of the studies show lower incidence of abscess ranging between 0.4 – 11%. [7,17,25,26]. Breast abscess also is commonest in the first 6 weeks post-partum, but may occur later [6,26]. Concerning relation between these complications and some factors, the study demonstrates that extreme of age in the study group is significantly related to type of infection whether complicated or not as complication was encountered in (81.2%) and (100%) below 20 years and above 40 years respectively (p=0.01). For young lactating women especially teenager mothers, the association may be attributable to inexperience and lacking proper support, however, the reason behind association with older lactating women (above 40 years) need to be explored.

On the other hand, there is significant association between parity and complications; complications are more frequent among primiparous women (69.6%) (P= 0.01). A significant association with period of lactation is also noted where highest frequency of complicated mastitis occurs in first 6 weeks (Puerperium) 42(72.4%) (P= 0.01). In contrast to our findings, many studies did not specify frequency of complications in relation to breast feeding duration or even parity. In reality, in most studies, lactational mastitis and its complications were studied in conjunction with non-lactational mastitis

Surprisingly, residence, occupation and education have not shown any significant relationship with the development of complication (p >0.05) while lack of antenatal care, first episode of mastitis, late presentation have shown relation to the high frequency of complication (0.014), (p=0.02), (p=0.01). Also complicated mastitis was found to be high in association with nipple trauma (p=0.11) and among women using herbal medicine (P=0.10). On other hand the current study failed to show significant associations encountered between dirty brace and amulet and complicated mastitis (P= >0.05). lastly, complicated mastitis appears to have less significant relationship with the type of breast infection where complicated mastitis was found to be a little pit higher among the patients of bilateral disease, as equal to (80.0%) (P= >0.08).

Conclusion

The affected women are from the rural area of Elnohud city in majority (94.9%), they are young (78.5%); below 30 years with teenager nursing mother representing 20.3%. Similar to other studies, mastitis is more frequent in the first 6 months. In comparison to many other studies, risk factors in our study are different, it is largely related to poor hygienic practice, improper feeding technique and history of mastitis. however, wearing tight para, using nipple cream, nipple piercing and using breast pumps were not even reported here. Complications rate is very high 80(50.6%) especially among younger women, primiparous, early lactation (Puerperium) lactation, women lacking antenatal care, late consultation, history of nipple trauma and using herbal medicine. Conversely, the affected breast and poor hygiene especially wearing dirty braces and amulets showed no relationship with frequency of complications. We recommend urgent intervention to raise the awareness about healthy breast feeding practice among women living in rural areas emphasizing on proper breast feeding technique, hygienic practice, urgent consultation and avoidance of using herbal medicine.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study which involvement human participation were in accordance with the ethical standards of institution review board of faulty of medicine and health sciences west kordufan university and the hospitals research committees. Also this work is in line with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and an additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

References

- Viduedo AFS, Leite JRC, Monteiro JCS, Reis MCG, Gomes-Sponholz FA, et al. (2015) Severe lactational mastitis: particularities from admission. Revista brasileira de enfermagem 68(6): 1116-1121.

- Delgado S, Arroyo R, Martín R, Rodríguez JM (2008) PCR-DGGE assessment of the bacterial diversity of breast milk in women with lactational infectious mastitis. BMC infec dis 8(1): 51.

- Kvist LJ, Scott JA, Lee AH, Binns CW (2008) The role of bacteria in lactational mastitis and some considerations of the use of antibiotic treatment. Breastfeed Med 3(1): 6.

- Khanal V, Scott JA, Lee AH, Binns CW (2015) Incidence of mastitis in the neonatal period in a traditional breastfeeding society: results of a cohort study. Breastfeed Med 10(10): 481-487.

- Kvist LJ, Larsson BW, Hall-Lord ML, Steen, Schalén C (2010) Toward a clarification of the concept of mastitis as used in empirical studies of breast inflammation during lactation. J Hum Lact 26(1): 53-59.

- Organization WHO (2000) Mastitis: causes and management. World Health Organization.

- Buescher ES, Hair PS (2001) Human milk anti-inflammatory component contents during acute mastitis. Cell Immunol 210(2): 87-95.

- Riordan JM, FH Nichols (1990) A descriptive study of lactation mastitis in long-term breastfeeding women. J Human Lact 6(2): 53-58.

- Foxman B, D'Arcy H, Gillespie B, Bobo JK, Schwartz K (2002) Lactation mastitis: occurrence and medical management among 946 breastfeeding women in the United States. Am j Epidemiol 155(2): 103-114.

- Jonsson S, M Pulkkinen (1994) Mastitis today: incidence, prevention and treatment. in Annales chirurgiae et gynaecologiae. Supplementum.

- Vogel ABL, Hutchison EA Mitchell (1999) Mastitis in the first year postpartum. Birth 26(4): 218-225.

- Fetherston C (1998) Risk factors for lactation mastitis. J Human Lact 14(2): 101-109.

- Scott JA, Robertson M, Fitzpatrick J, Knight C, Mulholland S (2008) Occurrence of lactational mastitis and medical management: a prospective cohort study in Glasgow. Int Breastfeed J 3(1): 21.

- Kvist LJ, Hall Lord ML, Rydhstroem H, Larsson BW (2007) A randomised-controlled trial in Sweden of acupuncture and care interventions for the relief of inflammatory symptoms of the breast during lactation. Midwifery 23(2): 184-195.

- Tang L, Lee AH, Qiu L, Binns CW (2014) Mastitis in Chinese breastfeeding mothers: a prospective cohort study. Breastfeeding Medicine 9(1): 35-38.

- Thompson JF, Roberts CL, Currie M, Ellwood DA (2002) Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: associations with parity and method of birth. Birth 29(2): 83-94.

- Mediano P, Fernández L, Rodríguez JM, Marín M (2014) Case–control study of risk factors for infectious mastitis in Spanish breastfeeding women. BMC preg childbirth 14(1): 195.

- Amir, Forster DA, Lumley J, McLachlan H (2007) A descriptive study of mastitis in Australian breastfeeding women: incidence and determinants. BMC Pub Health 7(1): 62.

- Egbe TO, Darlene Tufon Ngonsai , Robert Tchounzou, Marcelin Ngowe Ngowe (2015) Prevalence and risk factors of lactation mastitis in three hospitals in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Br J Med Med Res 13: 1-10.

- Kinlay JR, O'Connell DL, Kinlay S (2001) Risk factors for mastitis in breastfeeding women: results of a prospective cohort study. Aust N Z J Public Health 25(2): 115-120.

- Amir LH, Forster D, McLachlan H, Lumley J (2004) Incidence of breast abscess in lactating women: report from an Australian cohort. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 111(12): 1378-1381.

- SPencer JP (2008) Management of mastitis in breastfeeding women. Am Fam Physician 78(6): 727-731.

- Sales AdN, Vieira GO, Maria, Tatiana (2000) Puerperal Mastitis: Study of Predisposing Factors. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia 22(10): 627-632.

- Gollapalli V, Liao J, Dudakovic A, Sugg SL, Scott-Conner CE, et al. (2010) Risk factors for development and recurrence of primary breast abscesses. J Am College Surg 211(1): 41-48.

- Betzold CM (2007) An update on the recognition and management of lactational breast inflammation. J Midwifery Womens Health 52(6): 595-605.

- Branch-Elliman W, Golen TH, Gold HS, Yassa DS, Baldini LM, et al. (2011) Risk factors for Staphylococcus aureus postpartum breast abscess. Clin Infect Dis 54(1): 71-77.