An Evaluation of the Impact of Community Specialist Clinics (CSC) on a Local Community in London

Feray Ozdes1, Anwar Khan2* and Pasquale Giordano3

1Foundation Year 1 trainee, Princess Alexandra Hospital, England

2Senior Research Fellow Kings College (London), Ching Way Medical Centre, England

3Consultant Surgeon, Whipps Cross University Hospital and Ching Way Medical Centre, England

Submission: September 1, 2019; Published: September 17, 2019

*Corresponding author: Anwar Khan, Senior Research Fellow Kings College (London), Ching Way Medical Centre, England, United Kingdom

How to cite this article: Feray Ozdes, Anwar Khan, Pasquale Giordano. An Evaluation of the Impact of Community Specialist Clinics (CSC) on a Local Community in London. Open Access J Surg. 2019; 11(1): 555804. DOI: DOI:10.19080/OAJS.2019.10.555804.

Keywords: Care setting; NHS Operational target; Public satisfaction; Cost effective healthcare; Community clinics; Colorectal surgery

Background

Community specialist clinics (CSC) are consultant-led services run within a primary care setting [1]. Within recent years, the waiting times for referral to specialists has reached an all-time high [2,3]. The national waiting time target for referral to consultant-led treatment, known as Referral to Treatment (RTT), has been set at 18 weeks [2,4]. However, in 2019, this target was met for only 87% of patients, falling significantly below the NHS operational target of 92% [4]. If it is not possible for treatment to be provided within the target waiting times, the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) is responsible for offering alternative providers [2] which often adds further costs to the service. As well as waiting times, patient satisfaction and quality of care within the NHS is declining [5]. Public satisfaction with the NHS overall was as low as 53% in 2018 – a 3% point drop from the previous year and the lowest level since 2007 [5]. At the levels of funding provided, the NHS is struggling to meet demands and cost pressures are likely to worsen [3,6]. With CCGs also beginning to fall into financial deficit [7] at a time of increasing power and financial independence of general practitioners (GPs) [8], there has been a growing demand for CCGs to outsource their specialist services in order to ease the burden on their secondary care providers.

In 2001, a national evaluation of specialists’ clinics in primary care settings concluded that the benefits of community clinics included shorter waiting times for appointments, shorter waiting times at the clinics themselves, the need for fewer follow- up appointments, higher patient satisfaction, and lower personal costs to the patients such as those for travel and parking [9]. Nevertheless, the costs to the NHS per patient were found to be higher in community clinics when compared to secondary care outpatient clinics [9].

This paper aims to evaluate the impact of implementing a CSC on a local community in Waltham Forest, East London. The particular provider we will evaluate was established in 2008 and includes three specialist services; colorectal, gynaecology and dermatology. The data for the latter specialty was limited and therefore we will evaluate colorectal and gynaecology clinics only. We will aim to compare the impact of these services from three different perspectives; that of the NHS, the patients, and the doctors.

Methods

NHS

In order to compare the financial impact of community clinics to secondary care clinics, the cost to the CCG and therefore to the NHS, will be compared. Outpatient appointments for new patients, outpatient appointments for follow-up patients, and each individual outpatient procedure is coded for using a healthcare resource group (HRG) code. Each HRG code is valued by pre-determined tariffs set out by the care provider and the CCG at the start of each working year [10]. These tariffs paid to the CSC differ to those paid to secondary care providers, most likely due to the higher costs associated with running a hospital. As well as the tariffs paid to the providers, the CCG also pays an additional 21.28% market force factor (MFF) to the secondary care provider, but not to the CSC. An MFF, which varies between CCGs nationally, is an estimate of unavoidable cost differences between health care providers based on their geographical location [10,11]. This data should reflect the cost differences and therefore the financial impact on the NHS of each service provider.

Patients

The patients’ perspective will be evaluated using questionnaires voluntarily completed by patients at the end of CSC clinics. These will aim to provide qualitative information on the views and attitudes of patients to community-run clinics. Written feedback from patients will be observed and both positive and negative comments referring directly to the quality of the service will be evaluated. In addition, the questionnaires will be used to ascertain how long patients waited between their initial GP referral to clinic and their first CSC appointment. These waiting times will be compared to publically-accessible data on waiting times by the same NHS Trust’s secondary care clinics in the same year. This information should summarise the impact on patients of community clinics in comparison to secondary care clinics.

Doctors

The perspective of the doctors working in these clinics will be evaluated using questionnaires which will be sent to them via email. The specialists who complete these questionnaires may be either a GP with specialist interest (GPwSI) or a consultant in their specialty but must have at least one year’s experience in working in both community and secondary care clinics. The questionnaires will aim to gather information about the quality of care, advantages and disadvantages of both primary and secondary care outpatient clinics in their experience. This will enable a comparison of views and attitudes in each setting from a clinician’s point of view.

Results

NHS

Total costs were collected for the year commencing April 2018, for both primary and secondary care outpatient clinics. The data revealed that the cost to the CCG of funding both new and follow-up patient appointments, as well as for all outpatient procedures were higher for secondary care clinics than for CSCs. This was true for both colorectal and gynaecology clinics (Figures 1 & 2).

Patients

There was a 59.8% response rate for patient questionnaires after attending a CSC clinic, with 3204 responses out of the 5354 total visits to the clinics in the year commencing April 2018.

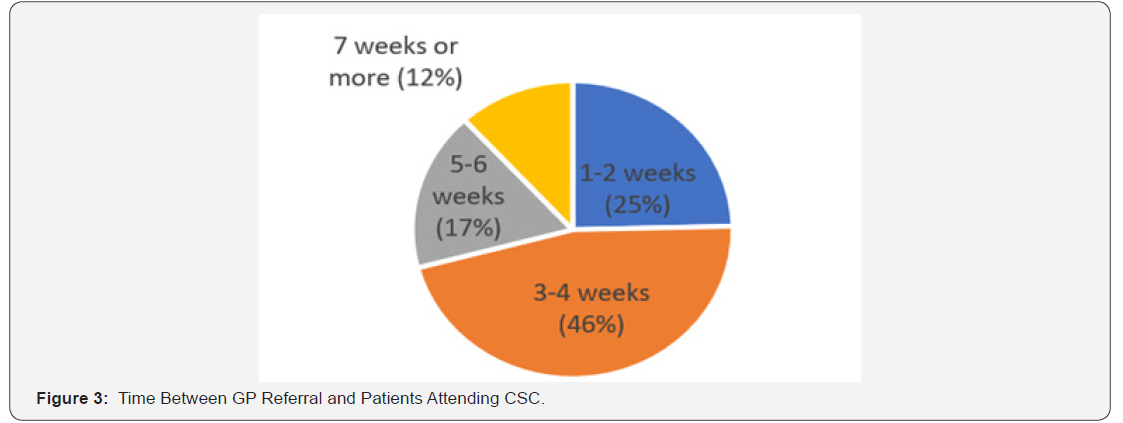

Waiting times from referral to clinic

According to CSC practice data, 100% of patients were offered appointments within 6 weeks of referral from their GP. However, patient questionnaire data from the CSC revealed that 88% of patients were actually seen within 6 weeks of their GP referral, which was attributed to patient preference, patient cancellations, or patients not arriving to their given appointments. Overall, the median waiting time for referral to this CSC fell between 2-3 weeks. Practice data also revealed that the mean waiting time from clinic appointment to undergoing a procedure with the CSC was 16 days, thereby giving a total RTT waiting time of approximately 5 weeks, falling well below the NHS 18 week RTT target. In fact, 100% of patients at this CSC met this 18 week target. Contrastingly, NHS England data for the same NHS trust reveals that only 85.5% of patients were meeting the 18 week RTT target in secondary care clinics in the same year (Figure 3).

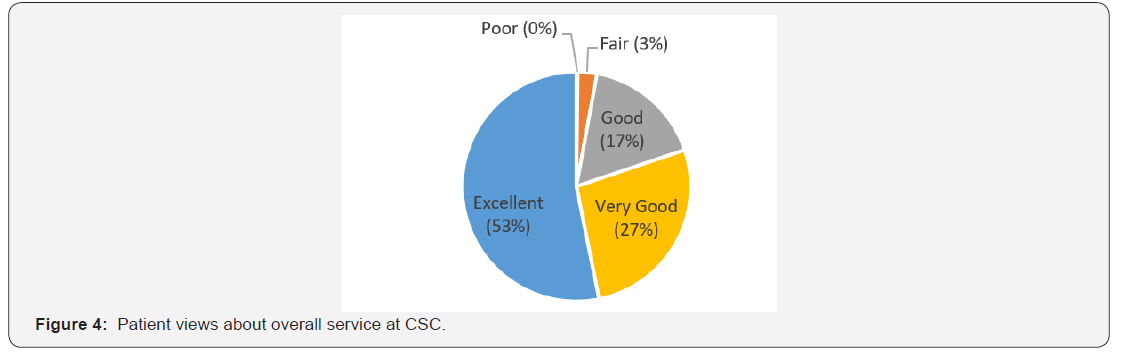

Quality of service

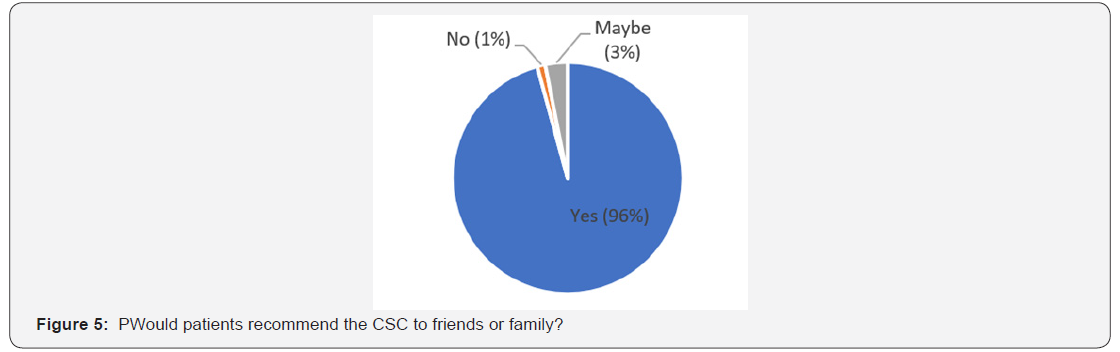

When asked to rank the overall service provided at the CSC, 80% of patients rated this as “excellent” or “very good”, while less than 1% rated it as “poor”. Moreover, 96% of respondents would recommend the service to friends and family (Figures 4 & 5).

Of the 3204 patients who completed the questionnaires, 436 left additional comments. Of these comments, 121 were relevant to the service provided as opposed to other factors such as the quality of the doctors and other staff members. Of all of the comments relevant to the service provided, 102 (84%) comments were positive while 19 (16%) were negative or suggested improvements that could be made to the service. Positive comments included forty patients commending the CSC’s “excellent service” with thirty eight patients using other positive descriptive terms for the service such as ‘brilliant’ or ‘outstanding’. Nine patients praised the service’s efficiency, punctuality and organisation. One patient commented that there were excellent parking facilities. Another stated that the CSC was very convenient and close to home, while one patient felt it was much better than being seen at the hospital. On the other hand, eight patients expressed the need for improved waiting times. Four patients asked for better waiting room facilities such as more space and chairs, and one commented that car parking was not always available. Overall, comments were generally positive, and the suggested improvements have been fed back to the practice for action.

Doctors

Eighteen doctors working at the CSC were sent a questionnaire via email. 10 doctors completed the questionnaire anonymously. 70% of respondents were male, while 30% were female. 70% were specialists in colorectal, while 30% specialise in gynaecology. 70% were consultants, while the other 30% of respondents were GPwSIs./p>

Waiting room times

When asked about how late clinics usually run in both primary and secondary care settings, doctors revealed that, on average, their secondary care clinics run later than their community clinics. In the CSC, 40% stated their clinics run on time, 40% claimed they run 5-15 minutes late, and 20% claimed clinics run 20-30 minutes late. Contrastingly, when asked about secondary care clinics, only 14% claimed their clinics were on time. Furthermore, 14% of secondary care clinics were said to run 5-15 minutes late, 43% run 20-30 minutes late, and 29% run more than 45 minutes late. These responses indicate that community clinics are, on average, more punctual than clinics for the same specialty in a secondary care setting (Figure 6).

Quality of care

Doctors rated the overall quality of care provided at the CSC, as perceived by them, higher than that of their secondary care clinics. 60% rated the quality of care at the CSC as ‘excellent’. which corresponds similarly to the 53% of patients who also gave the service this rating. Meanwhile, 30% of doctors rated the service as very good, and 10% as good. In regard to the secondary care clinics, the results were less positive. 20% of doctors rated the quality of care provided at secondary care clinics as excellent, 20% rated it as very good, 30% said it was good, 20% claimed it was fair, while 10% claimed it was poor (Figure 7).

Doctors’ views on CSC

100% of respondents believed the CSC was of benefit to the local community. The main advantages of the CSC, as described by doctors, tended to relate to the locality and ease of access of the service, particularly easier and cheaper travel and parking for both the patients and staff. Timely referral from CSC to local endoscopy services was also highlighted by several practitioners as an advantage to patients, as was improved waiting times from referral and waiting times at clinics themselves. The continuity of care provided at CSC was also commended. Some felt that the availability of on-site treatments such as haemorrhoid injections and banding was practical and, again, improved patients’ waiting times for referral to treatment. Some doctors believed that having a community clinic allowed them to cut down on unnecessary referrals to their secondary care clinics, consequently improving their efficiency when working at the hospital. Many believed it was well organised and well-staffed, particularly admin staff which lightens the burden on doctors so that they can focus on clinical aspects. This also means more time can be allocated to meeting patient needs and as a consequence doctors feel that they are able to provide better care. The lack of interruption from the rest of the hospital while working in community was also a benefit.

As for disadvantages of the CSC, some doctors claimed they were not always able to access information from patient’s hospital notes. Additionally, results of recent investigations are not immediately available in community clinics and do not always arrive in time for patients’ follow-up appointments. Numerous doctors claimed that a disadvantage of working in the community was the use of paper notes rather than a centralised electronic system.

s’ views on secondary care clinics

The main advantage of secondary care clinics for many doctors was the fact that all services were on-site, and more facilities were available and accessible. There is also the possibility of seeing specialist nurses where appropriate. Additionally, all results of investigations taken in secondary care are immediately available in clinic. Some doctors felt that always having other specialists on site from whom a second opinion could be sought was an advantage of working in secondary care. Moreover, the clinics in hospital were felt to be well-staffed and well-equipped.

On the other hand, most respondents felt that the long waiting lists in hospital were a major disadvantage. They also felt clinics were overbooked and therefore waiting times in clinic can often be very long, as were waiting times for many procedures. Some felt that the care was depersonalised in hospital and patients were not always able to see the same consultant. Accessibility, travel, and the cost of parking was highlighted as a disadvantage for patients and staff. Some felt the hospital was a more stressful environment to both work and be treated. Some feel they are overworked in secondary care and the system does not value its staff.

Conclusion

This clinic not only provides cost effective healthcare (below the national tariffs) but also has good satisfaction ratings by both staff and patients. It also provides a good learning environment for both surgical trainees and GPs wanting to develop a special interest in colorectal surgery.

References

- CSC (2019) Community Specialist Clinics.

- Parkin E, Bellis A (2018) NHS maximum waiting times standards and patient choice policies, Briefing paper. House of Commons Library.

- Anon (2016) Who is to blame for the NHS funding crisis, a funding squeeze is leaving the NHS overwhelmed.

- NHS (2019) Statistics - Consultant-led Referral to Treatment Waiting Times.

- The King’s Fund (2019) Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2018 Results from the British Social Attitudes survey. The King’s Fund.

- Lafond S, Charlesworth A, Roberts A, Health (2016) A perfect storm: an impossible climate for NHS providers’ finances? an analysis of NHS finances and factors associated with financial performance. The Health Foundation., London, United Kingdom.

- Anon (2016) Is the NHS Underfunded?

- Baird B, Reeve H (2018) Innovative models of general practice. The King’s Fund London, United Kingdom.

- Bowling A, Bond M (2001) A national evaluation of specialists’ clinics in primary care settings. Br J Gen Pract 51(465): 264-269.

- NHS England and NHS Improvement (2016) 2017/18 and 2018/19 National tariff payment system. NHS Improvement Publication code: P 04/16, NHS England Publications Gateway Reference: 06227, United Kingdom.

- Monitor (2013) A guide to the Market Forces Factor. NHS England. Publication code: IRG 31/13, NHS England Publications Gateway Reference: 00883, United Kingdom.