Giant Hiatal Hernia with Pancreas Herniation

Sadi A Abukhalaf1*, Adham M Amro1, Muath A Baniowda1, Rami A Misk2, Radwan Abukarsh3, Ihsan Ghazzawi3, Nathan M Novotny4,5 and Tareq Z Alzughayyar1

1Faculty of Medicine, Al Quds University, Jerusalem, Palestine

2Faculty of Medicine, An-Najah National University, Palestine

3Palestine Red Crescent Society Hospital, Palestine

4Section of Pediatric Surgery, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, USA

5Palestine Medical Complex, Ramallah, Palestine

Submission: July 03, 2019; Published: August 06, 2019

*Corresponding author: Sadi A Abukhalaf, Faculty of Medicine, Al Quds University, Jerusalem, Palestine

How to cite this article: Sadi A Abukhalaf, Adham M Amro, Muath A Baniowda, Rami A Misk, Radwan Abukarsh. Giant Hiatal Hernia with Pancreas Herniation. Open Access J Surg. 2019; 10(5): 555800. DOI: DOI:10.19080/OAJS.2019.10.555800.

Abstract

Pediatric hiatal hernia is a rare congenital anomaly with congenital giant hiatal hernia being the rarest subtype. The congenital giant hiatal hernia has never been reported to contain pancreas. We report an extremely rare case of congenital giant hiatal hernia presented with respiratory distress and rapid deterioration of the respiratory function. The patient was found to have unreported intraoperative findings of colon and pancreas hiatal sac contents. Congenital giant hiatal hernia requires prompt intervention largely due to the risk of morbidity and mortality. The best option for management is surgical repair with an open or laparoscopic approach.

Introduction

Hiatal hernia occurs when abdominal viscera herniates into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus due to abnormal gastro-esophageal junction [GEJ] and is rarely seen in pediatrics [1]. Hiatal hernia is classified into four types according to the position of the GEJ and the extent of the herniated stomach and other organs into the thoracic cavity [2]. Type IV, the rarest type, is associated with large defects in diaphragmatic hiatus which allow stomach and other intra-abdominal organs such as colon, small intestine, spleen and pancreas to herniate into thorax and occurs primarily in adults [3]. Congenital giant hiatal hernia, a type IV hernia, is a very rare entity during childhood and is usually associated with high morbidity and mortality [4]. A study showed that adult hiatal hernia containing pancreas is present in a few more than 10 cases worldwide [5]. Pancreas herniation was not reported in any of the reported congenital giant hiatal hernias in the literature [5]. To the best of our knowledge, we report the first case of a congenital giant hiatal hernia in which stomach and “freely moving colon and pancreas” herniate through the diaphragmatic hiatus.

Case Presentation

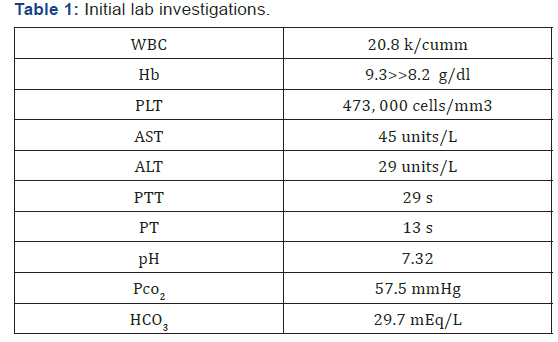

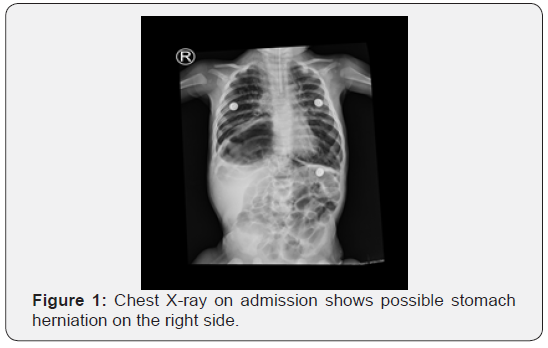

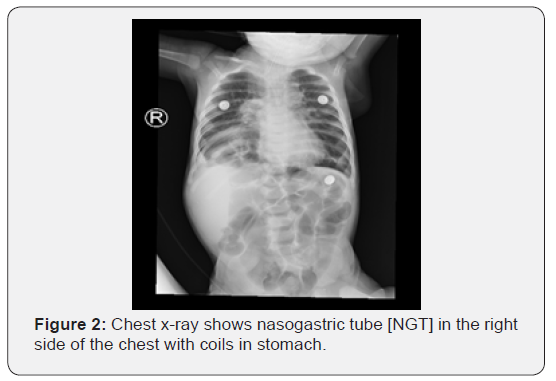

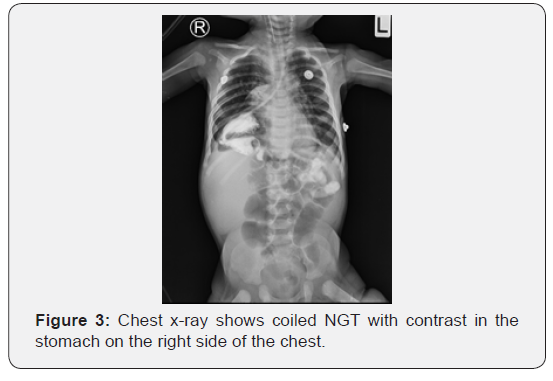

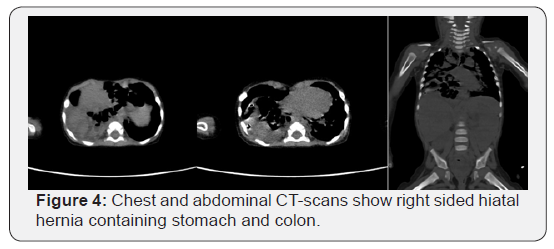

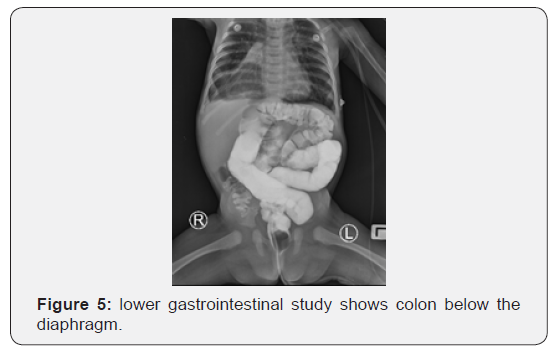

A four-month-old female infant was admitted to our hospital with symptoms of respiratory distress. The infant was in her usual state of health until two days prior to admission, when she started to have non-productive cough, runny nose and difficulty of breathing. A day prior admission, her condition worsened as she developed cyanosis, decreased activity, lethargy and worsening of the cough. There was no history of fever, vomiting, diarrhea, skin rash, trauma or previous similar episodes. Parents are first degree relatives. One male sibling had a pyloric stenosis repair at the age of 22 days and an unknown hiatal hernia repair at the age of four months. At the age of two months, our patient was found to have poor weight gain and was prescribed a higher caloric formula but without improvement. On admission, her vital signs were temperature of 35.5 C, SPO2 of 72%, blood pressure of 99/59 mmHg, Heart rate of 176 bpm, and respiratory rate of 60 breaths/min. Signs of respiratory distress were evident. Bowel sounds were audible on the right side of the chest with decreased breath sounds. Abdomen was scaphoid. Abnormal labs are summarized in table 1. A chest x-ray showed stomach on the right side of thorax (Figure 1). Nasogastric tube [NGT] was inserted and a chest x-ray showed NGT in the right side of the chest with coils in stomach and shifting of mediastinum to the left side (Figure 2). Contrast was introduced via NGT and showed coiled NGT in the stomach on the right side of the chest (Figure 3). An esophagoscopy showed the esophageal length of 18 cm confirming adequate length of the esophagus to reach the abdomen.

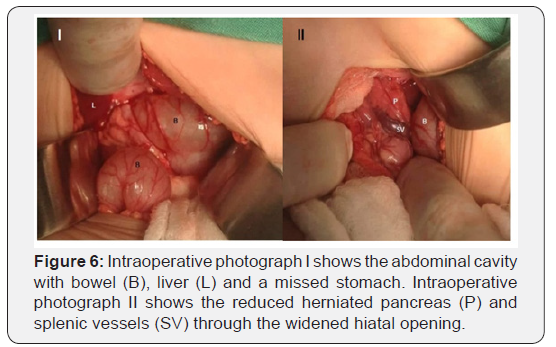

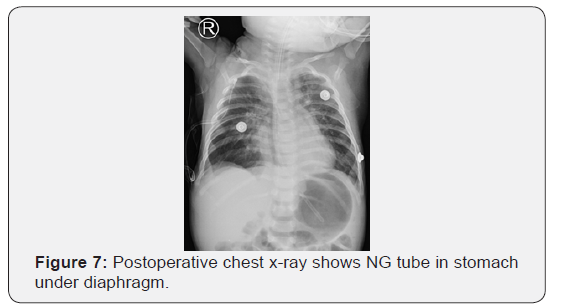

During an open operation, the stomach was not in the abdomen, and by an NGT palpation, the stomach was identified in the right thorax and pulled back to the abdominal cavity. Shortly, a pancreatic tissue with splenic vessels was identified. The hiatal hernia was found to contain parts of the bowel, the whole stomach, pancreas, and splenic vessels and herniated to the right side of the thorax with completely intact diaphragm confirming the diagnosis of congenital giant hiatal hernia and excluding any concomitant congenital diaphragmatic hernias (Figure 6). The contents were reduced to abdomen, hernia sac was excised with release of the lower esophagus, and fundoplication was performed with gastropexy (Figure 7). The infant had uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on the seventh postoperative day.

Discussion

Hiatal hernia is classified into four types based on the position of the gastroesophageal junction [GEJ] and the extent of stomach herniation and other organs into the thoracic cavity [2]. The incidence rates for type І, II, III and IV are 95%, 0.4%, 4.5%, and 0.1% respectively [6]. Type І hiatal hernia occurs due to widening of the crural diaphragm (which forms the esophageal hiatus) and looseness of the phrenoesophageal membrane resulting in transient movement of the GEJ out of the abdomen [7,8]. Type II hiatal hernia represents a true herniation of the fundus of the stomach into the chest with a normally localized GEJ [8]. In type III and IV hiatal hernias, the GEJ is abnormally localized in the thorax due to laxity of the gastrosplenic and gastrocolic ligaments, causing widening of the esophageal hiatus over time. Type III hiatal hernia is an incarcerated stomach or a fixed intrathoracic stomach [9]. Type IV hiatal hernia is characterized by the presence of abdominal organs other than stomach [3]. The commonly reported herniated organs are small intestine, transverse colon, and spleen [3]. Diaphragmatic pancreatic herniation is an extremely rare condition and was reported in only 11 adult cases with no pediatric reported cases [5,10].

Paraesophageal hiatal hernia [PEH] consists of type II, III, and/or IV hiatal hernias that is rarely present in the pediatric population [11]. Most of PEH that is reported in pediatric age groups are caused by complications of gastroesophageal surgeries as fundoplication and esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula repair.

However, congenital PEH [CPEH] accounts only for 3.5–5% of all hiatal hernias and has been reported only in very few case reports and series [12]. CPEH may be associated with other congenital anomalies that may have a tremendous impact on mortality rates [13]. Giant hiatal hernia defines a herniation of more than 30% of the stomach through the diaphragmatic hiatus [14]. Sliding hiatal hernia [15-18] and progression of paraesophageal hiatal hernia [19-21] are seen in a substantial number of cases of giant hiatal hernia. However, the definitive cause remains unclear [17-20]. In literature, many reported cases exhibit autosomal dominant familial pattern inheritance between siblings and across generations [22-26]. Although our patient and his sibling had hiatal hernias, their parents did not have any suggestive history of being diseased or having surgical repairs of any kind.

Congenital giant hiatal hernia [CGHH] is the rarest subtype of hiatal hernia in pediatric age group. CGHH can present incidentally without symptoms or may present with gastric volvulus, hematemesis, vomiting, failure to thrive, respiratory distress, frequent respiratory tract infections, cyanosis, cough and /or excessive crying [13]. Associated symptomatic and asymptomatic anemia was reported as well [27]. Our patient had hemoglobin levels of 9.3 g/dl that’s decreased to 8.2 g/dl in a few days, but he continued to be asymptomatic for anemia.

CGHH carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality rendering early diagnosis and prompt surgical treatment crucial [28]. CGHH may be misdiagnosed with other congenital anomalies as congenital diaphragmatic hernia [CDH], eventration of diaphragm, lobar emphysema, pneumatocele, pneumothorax, pleural effusion and esophageal atresia [29].

Upper gastrointestinal series with barium is essential for diagnosis [20,30]. However, it is difficult to differentiate between CDH and hiatal hernia [4,20]. Although the nasogastric tube can exclude pneumatocele, pneumothorax and pleural effusion, it is not diagnostic.

Surgery is the only available treatment for hiatal hernia and should include resection of the hernia sac, reduction of the stomach and other organs into abdomen, closing the hiatus, antireflux procedures and/or achieving sufficient gastropexy [31]. Laparoscopic and open surgical approaches are possible. One study found that the laparoscopic approach has more advantages over the open approach in that it has a shorter time to oral intake, shorter time to full feeding, low mortality rate and acceptably low recurrence rate [32,33]. However, proponents of the open approach argue that laparoscopic approach is associated with a higher recurrence rate and intraoperative and postoperative complications [34-36]. Intraoperative complications for laparoscopic approach are pneumothorax, splenic injury and crura laceration and conversion to open approach [36]. laparoscopic approach may be safe, feasible, and cost-effective and could be the preferred choice of treatment for experienced surgeons [37-40]. The frequently reported postoperative complications are bowel obstruction, intussusception, dysphagia, esophageal leak, breakdown of the repair, postoperative gastroesophageal reflux and hiatal hernia recurrence [41]. Hiatal hernia recurrence has been declined largely due to performing gastropexy and fundoplication procedures and is reported to be as high as 7% [31,33]. In addition, anti-reflux procedures as fundoplication are recommended with hiatal hernia repair to achieve a favorable postoperative course [18].

Conclusion

We presented the first case of congenital giant hiatal hernia with the unreported intraoperative findings of pancreas above the diaphragm. Congenital giant hiatal hernia represents the rarest type of pediatric hiatal hernias and carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality rendering prompt diagnosis and surgical intervention vital. Prognosis can be favorable if low threshold for surgery is committed.

Patient consent

The patient consent was obtained by the infant’s father. And the father accepted the final edition of the article.

Conflict of interest

The following authors have no financial disclosures: S.A, A.A, M.B, R.M, R.A, I.G, N.N, and T.A.

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for Authorship.

References

- Sriram P, Femitha P, Nivedita Mondal, Prakash V, Bharathi B, et al. (2011) Neonatal Hiatal Hernia-A rare case report. Curr Pediatr Res 15: 55-57.

- Banimostafavi, Elham Sadat, Maryam Tayebi (2018) Large hiatal hernia with pancreatic body herniation: Case-report. Ann Med Surg 28: 20-22.

- Chase Dean, Denzil Etienne, Bianca Carpentier, Jerzy Gielecki, Shane Tubbs, et al. (2012) Hiatal hernias. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 34(4): 291-299.

- Bataineh ZA, Rousan LA, Abu Baker A, Wahdow H, Kiwan RN, et al. (2104) Congenital massive hiatus hernia type IV; initial experience with laparoscopic repair in young infant. Hernia 18(3): 427-429.

- Jäger Tarkan, Neureiter D, Nawara C, Dinnewitzer A, Ofner D, et al. (2013) Intrathoracic major duodenal papilla with transhiatal herniation of the pancreas and duodenum: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 5(6): 202.

- Krause William, Jennifer Roberts, Romel J, Garcia Montilla (2016) Bowel in chest: type IV hiatal hernia. Clin Med Res 14(2): 93-96.

- Kissane, Nicole A, David W Rattner (2013) Paraesophageal and other complex diaphragmatic hernias. Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. Elsevier Medicine, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 494-508.

- Kahrilas Peter J, Hyon C Kim, John E, Pandolfino (2008) Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 22(4): 601-616.

- Hefler Joshua (2015) Case report: Type IV paraesophageal hernia. University of Ottawa Journal of Medicine 5(1): 36-39.

- Saxena Pankaj, Konstantinov IE, Koniuszko MD, Ghosh S, Low VH, et al. (2006) Hiatal herniation of the pancreas: diagnosis and surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 131(5): 1204-1205.

- Di Francesco Stefania, Lanna MM, Napolitano M, Maestri L, Faiola S, et al. (2015) A case of ultrasound diagnosis of fetal hiatal hernia in late third trimester of pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol.

- Zhang, Chao, Liu D, Li F, Watson DI, Gao X, et al. (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic mesh versus suture repair of hiatus hernia: objective and subjective outcomes. Surg Endosc 31(12): 4913-4922.

- Jetley Nishith Kumar, Ali Hassan Al-Assiri, Dawood Al Awadi (2009) Congenital para esophageal hernia: a 10 year experience from Saudi Arabia. Indian J Pediatr 76(5): 489-493.

- Wongrakpanich, Supakanya, Hilit Hassidim, Wikrom Chaiwatcharayut, Wuttiporn Manatsathit (2016) A case of giant hiatal hernia in an elderly patient: When stomach, duodenum, colon, and pancreas slide into thorax. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics 7(3): 112-114.

- Pearson FG, Cooper JD, Ilves R, Todd TR, Jamieson WR (1983) Massive hiatal hernia with incarceration: a report of 53 cases. Ann Thorac Surg 35(1): 45-51.

- Arima T (1988) Hiatal herniation of the colon in an infant. International surgery 73(3): 196-197.

- Maziak Donna E, Thomas RJ Todd, Griffith Pearson F (1998) Massive hiatus hernia: evaluation and surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 115(1): 53-62.

- Herek Özkan, Nergül Yıldıran (2002) A massive hiatal hernia that mimics a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. An unusual presentation of hiatal hernia in childhood: report of a case. Surg Today 32(12): 1072-1074.

- Senocak ME, Büyükpamukçu N, Hiçsönmez A (1990) Massive paraesophageal hiatus hernia containing colon and stomach with organo-axial volvulus in a child. Turk J Pediatr 32(1): 53-58.

- Al Arfaj, A Latif, Mohd Saleem Khwaja, PURU Upadhyaya (1991) Massive hiatal hernia in children. Eur J Surg 157(8): 465-468.

- Geha Alexander S, Massad MG, Snow NJ, Baue AE (2000) A 32-year experience in 100 patients with giant paraesophageal hernia: the case for abdominal approach and selective antireflux repair. Surgery 128(4): 623-630.

- Carré IJ, P Froggatt (1970) Oesophageal hiatus hernia in three generations of one family. Gut 11(1): 51-54.

- Chaiken BH (1968) Familial occurrence of esophageal hiatus hernia. Gastroenterology. Independence Square West Curtis Center, Ste 300, PA 19106-3399, Wb Saunders Co, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 54(6).

- Chana J, Crabbe DCG, Spitz L (1996) Familial hiatus hernia and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur J Pediatr Surg 6(3): 175-176.

- Carre IJ, Johnston BT, Thomas PS, Morrison PJ (1999) Familial hiatal hernia in a large five generation family confirming true autosomal dominant inheritance. Gut 45(5): 649-652.

- Hubert, Bruce C, William M Toyama (1987) Familial right thoracic stomach. Pediatrics 79(3): 430-431.

- Karpelowsky, Jonathan S, Nicky Wieselthaler, Heinz Rode (2006) Primary paraesophageal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg 41(9): 1588-1593.

- Garvey, Erin M, Daniel J Ostlie (2017) Hiatal and paraesophageal hernia repair in pediatric patients. Semin Pediatr Surg 26(2).

- Yadav K, NA Myers (1997) Paraesophageal hernia in the neonatal period—another differential diagnosis of esophageal atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 12(5-6): 420-421.

- Stiefel Dorothea, Willi UV, Sacher P, Schwöbel MG, Stauffer UG (2000) Pitfalls in therapy of upside-down stomach. Eur J Pediatr Surg 10(03): 162-166.

- Al-Salem, Ahmed H (2000) Congenital paraesophageal hernia in infancy and childhood. Saudi Med J 21(2): 164-167.

- Carre IJ, Johnston BT, Thomas PS, Morrison PJ (1999) Familial hiatal hernia in a large five generation family confirming true autosomal dominant inheritance. Gut 45(5): 649-652.

- Petrosyan Mikael (2018) Congenital paraesophageal hernia: Contemporary results and outcomes of laparoscopic approach to repair in symptomatic infants and children. J Pediatr Surg 54(7): 1346-1350.

- Low Donald E, Trisha Unger (2005) Open repair of paraesophageal hernia: reassessment of subjective and objective outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 80(1): 287-294.

- Trus Thadeus L, Bax T, Richardson WS, Branum GD, Mauren SJ, et al. (1997) Complications of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg 1(3): 221-228.

- Dahlberg Peter S, Deschamps C, Miller DL, Allen MS, Nichols FC, et al. (2001) Laparoscopic repair of large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg 72(4): 1125-1129.

- Kundal, Anjani Kumar, Noor Ullah Zargar, Anurag Krishna (2008) Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatus hernia in infancy. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 13(4): 142.

- Van der Zee, DC, Bax NM, Kramer WL, Mokhaberi B, Ure BM (2001) Laparoscopic management of a paraesophageal hernia with intrathoracic stomach in infants. Eur J Pediatr Surg 11(1): 52-54.

- Van Niekerk, Martin L (2011) Laparoscopic treatment of type III para-oesophageal hernia S Afr J Surg 49(1): 47-48.

- Bettolli M, SZ Rubin, A Gutauskas (2008) Large paraesophageal hernias in children. Early experience with laparoscopic repair. Eur J Pediatr Surg 18(2): 72-74.

- Karpelowsky, Jonathan S, Nicky Wieselthaler, Heinz Rode (2006) Primary paraesophageal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg 41(9): 1588-1593.