Low Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma in Perimenopausal Patient. A Case

Sofoudis Chrisostomos1*, Vasileiadou Dimitra1, and Triantafyllidi Vera1, Manes Konstantino2, Papamargaritis Eythimios1 and Gerolymatos Andreas1

1Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Konstantopouleio General Hospital of Nea Ionia, Athens, Greece.

2Department of Surgery, Konstantopouleio General Hospital of Nea Ionia, Athens, Greece

Submission: April 29, 2019;Published: May 22, 2019

*Corresponding author: Chrisostomos Sofoudis, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Konstantopouleio General Hospital of Nea Ionia, Ippokratous 209, 11472, Athens, Greece

How to cite this article: Sofoudis C, Vasileiadou D, Triantafyllidi V, Manes K, Papamargaritis E, Gerolymatos A. Low Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma in Perimenopausal Patient. A Case. Open Access J Surg. 2019; 10(4): 555792. DOI:10.19080/OAJS.2019.10.555792.

Abstract

Introduction: Endometrial stromal tumors (ESS) account for less than 1% of all uterine tumors. Low-grade ESS have favorable pathologic features and a good prognosis, if diagnosed at an early stage.

Case Report: Here we report on a 43-year-old patient who presented with menometrorrhagia due to uterine fibroids, diagnosed after ultrasound and MRI examinations. She underwent a subtotal abdominal hysterectomy without bilateral salpingooopherectomy (BSO) and histology report showed a low-grade ESS. The patient then underwent a trachelectomy and BSO. No adjuvant treatment was administered.

Discussion: The most common cause of an enlarged uterus represents leiomyomas. However, there is a small risk of malignancy (1 in 500) in patients undergoing leiomyoma surgery. Preoperative assessment is often controversial; therefore, the diagnosis of malignancy is set after surgery.

Conclusion: Given the low prevalence of uterine sarcomas, the risk of a missed diagnosis of malignancy preoperatively does not seem to outweigh exposing more women to the risks of unnecessary hysterectomy.

Keywords: Endometrial Stromal Tumor, Uterine Masses, Leiomyoma Surgery

Introduction

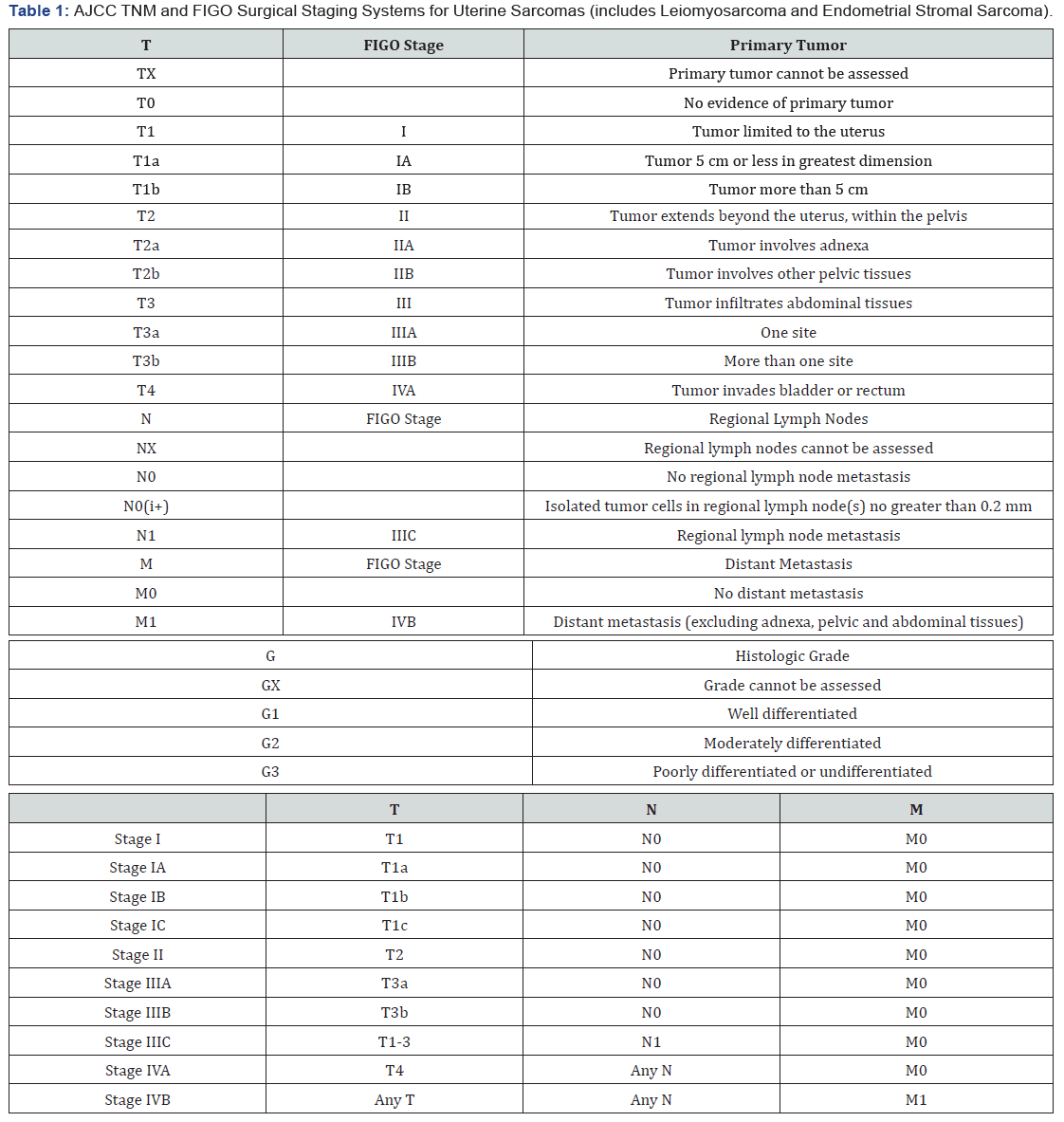

Sarcomas account for three to nine percent of all uterine malignancies and are much less frequent than endometrial carcinomas (epithelial neoplasms) [1]. Uterine sarcomas stem from proliferating cell populations in the myometrium or connective tissue elements within the endometrium. Compared to endometrial carcinomas, uterine sarcomas behave more aggressively and are associated with a poorer prognosis. According to the current WHO Classification of Tumours of the Female Reproductive Organs [2], the most common types of uterine sarcoma are the endometrial stromal neoplasms, the undifferentiated uterine sarcomas and the uterine leiomyosarcoma [3]. Endometrial stromal tumors account for less than 1% of all uterine tumors [4] are further classified into five categories: endometrial stromal nodule (ESN), low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS), high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS), undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (UUS), and uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor (UTROSCT) [5], classified by invasion into surrounding myometrium and the degree of differentiation. The TNM and FIGO staging systems are presented in Table 1.

Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas (LG-ESS) are characterized by small cells with low-grade cytology and features resembling stromal cells in proliferative endometrium (<5 MF per 10 HPF), having nonetheless myometrial and vascular invasion as well as a potential for recurrence and metastasis [3]. They account for about 20% of uterine sarcomas [6]. They affect primarily women in the perimenopausal age group, amd more than half of patients are diagnosed premenopausally [4,7]. Several risk factors have been associated with LG-ESS, such as diabetes, obesity, younger age at menarche and tamoxifen use [8]. The most common symptoms and signs are abnormal uterine bleeding, a uterine mass, pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea [9].

Also the patient may be asymptomatic and present with an incidental finding on clinical or ultrasound examination. It can often present as an endometrial polyp and most cases (60%) present with FIGO stage I disease while only 20% present with stage IV metastatic disease [8]. Uterine sarcomas tend to spread via intraabdominal, lymphatic or hematogenous routes. The most frequent site of extrauterine pelvic extension is the ovary, while hematogenous spread is most often to the lungs.

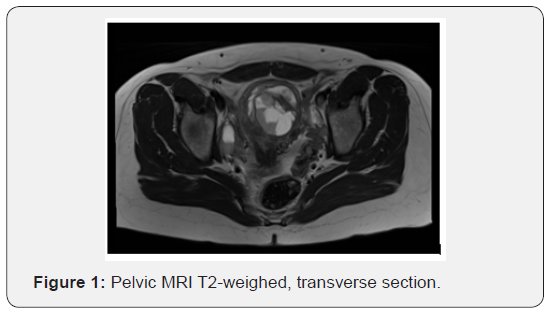

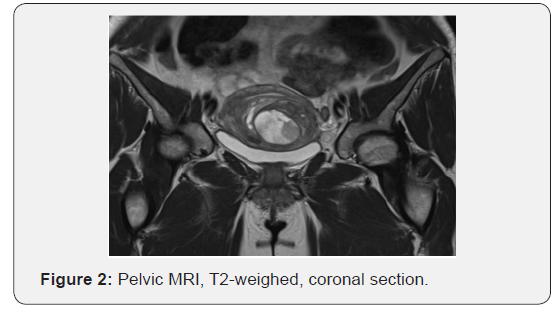

The medical history should include an assessment of risk factors associated with uterine sarcoma. Clinical examination may reveal an enlarged uterus. Serum tumor markers (CA-125 and lactate dehydrogenase) have been reported to be elevated in uterine sarcoma but they are not diagnostic [10]. Preoperative imaging cannot reliably differentiate between benign fibromas and uterine sarcomas. Suspicious ultrasound findings may include multiseptated cystic areas and multiple small areas of cystic degeneration [11]. On magnetic resonance imaging LGESS may appear as a polypoid endometrial mass with low signal on T1-weighted images and heterogeneously increased high T2 signal. Myometrial and lymph vascular invasion can be noted. Contrast enhancement is moderate and often heterogeneous [12]. However these findings cannot set the definite diagnosis of malignancy.

Regarding the management of LG-ESS, surgery is the most important procedure, with hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy (BSO) being the procedure of choice. LG-ESS seems to be sensitive to hormones, BSO seems to be quite important in its management, as it ceases hormone production [9]. Whether systematic lymphadenectomy is needed is unclear. Stage I LG-ESS does not require adjuvant treatment. Stage II to IV disease may be managed with adjuvant endocrine treatment, while radiation therapy may sometimes be considered [13]. The prognosis of LG-ESS is favorable. Disease stage is the most important prognostic factor, as the 5-year overall survival rate for Stage I is more than 90% but is decreased to 50% for Stage III and IV. The most common sites for recurrence are the pelvis and abdomen [9].

Case

A 43-year-old parous patient presented to our Gynecology Clinic for surgical management of uterine leiomyomas causing menometrorrhagia. Ultrasound examination revealed two leiomyomas. Furthermore, following MRI depiction revealed more than three leiomyomas, the largest being 6 x 4.5 cm in dimensions. (Figures 1 & 2) The patient’s medical and surgical history was insignificant and the tumor markers were negative. Pap smear free for malignancy. After preoperative assessment the patient was led to surgery where she underwent a subtotal abdominal hysterectomy without salpingooopherectomy (as it was her preference to preserve the cervix and the adnexae).

Her intraoperative and postoperative course was uneventful. Histology report showed a low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS). After the Multidisciplinary Team meeting, it was decided that the patient undergo prophylactic trachelectomy and bilateral salpingoophorectomy. Indeed, the histology report was negative for malignancy and it was decided at the Multidisciplinary Team meeting that the patient should be followed up every six months for three years and yearly after that. The patient is alive and disease-free nine months after the operation.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of an enlarged uterus includes many etiologies such as a benign leiomyoma, variants of uterine leiomyomas, adenomyoma or diffuse adenomyosis, uterine sarcoma, uterine carcinosarcoma, endometrial carcinoma, metastatic disease, pregnancy and hematometra. Endometrial stromal tumors account for less than 1% of all uterine tumors. On the other hand, benign leiomyomas (fibroids) are the most common pelvic neoplasm in women (lifetime risk 70-80%). This fact poses the important issue of preoperative differentiation between the common situation of leiomyomatosis versus a malignant uterine tumor, as it interferes with appropriate management, especially in the era of uterine-sparing alternatives to hysterectomy.

On one hand, implementation of minimal procedures such as myomectomy and morcellation may cause the dissemination of a neoplasm, on the other hand, it is equally important to avoid unnecessary surgery for the sole purpose of excluding the rare possibility of malignancy. In systematic reviews of women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for a myometrial mass, the prevalence of sarcoma is approximately 0.2% (1 in 500) in most studies [14].

Since no imaging or laboratory modality is able to reliably differentiate between a fibroid and a malignant tumor, risk factors should be carefully assessed preoperatively. Increasing age and postmenopausal status are important risk factors, therefore a new or growing uterine mass should warrant further evaluation. Also, failure of a leiomyoma to respond to treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist may be an indication for further investigation. During intraoperative evaluation some features may raise suspicion of malignancy, however a frozen section cannot reliably exclude it.

Definitive diagnosis is set after pathologic examination and further management may sometimes be needed. In accordance with the treatment of uterine leiomyosarcomas, if a subtotal hysterectomy or myomectomy was performed, trachelectomy and BSO are reasonable. If morcellation was performed, surgical exploration could be considered to check for residual disease.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no financial interest with respect to this manuscript.

Conclusion

Endometrial stromal sarcomas are uterine neoplasms with a favorable prognosis, depending on the stage at diagnosis. Several clinical features may raise suspicion of malignancy of a presumed leiomyoma, however definite diagnosis is confirmed with pathologic examination. Given the low prevalence of uterine sarcomas, the risk of a missed diagnosis of malignancy preoperatively does not appear to outweigh exposing more women to the risks of an unnecessary hysterectomy.

References

- Nordal RR, Thoresen SO (1997) Uterine sarcomas in Norway 1956-1992: incidence, survival and mortality. Eur J Cancer 33(6): 907-911.

- Kurman RJ Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH (2014) WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2019) Uterine Neoplasms.

- Prat J, Mbatani (2015) Uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 131 Suppl 2: S105-S110.

- Conklin CM, Longacre TA (2014) Endometrial stromal tumors: the new WHO classification. Adv Anat Pathol 21(6): 383-393.

- Clement PB, Young RH (2013) Mesenchymal and Mixed Epithelial–Mesenchymal Tumors of the Uterine Corpus and Cervix in Atlas of Gynecologic Surgical Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences 245-251.

- Nucci MR (2016) Practical issues related to uterine pathology: endometrial stromal tumors. Mod Pathol 29 Suppl 1: S92-S103.

- Amant F, Floquet A, Friedlander M, Kristensen G, Mahner S, et al. (2014) Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for endometrial stromal sarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24 (9 Suppl 3): S67-S72.

- Horng HC, Wen KC, Wang PH, Chen YJ, Yen MS, et al. (2016) Uterine sarcoma Part II-Uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma: The TAG systematic review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 55(4): 472-479.

- Memarzadeh S, Berek JS (2017) Uterine sarcoma: Classification, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate.

- Park GE, Rha SE, Oh SN, Lee A, Lee KH, et al. (2016) Ultrasonographic findings of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma of the uterus with a focus on cystic degeneration. Ultrasonography 35(2): 124-130.

- Santos P, Cunha TM (2015) Uterine sarcomas: clinical presentation and MRI features. Diagn Interv Radiol 21(1): 4-9.

- Gaillard S, Secord AA (2019) Classification and treatment of endometrial stromal sarcoma and related tumors and uterine adenosarcoma. UpToDate.

- Stewart EA (2018) Differentiating uterine leiomyomas (fibroids) from uterine sarcomas. UpToDate.