Extensive Subcutaneous Emphysema after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, two Cases Reports

Ahmed Elsaady1*, Ragab Elsherbeny2 and Ashraf Elzaeem3

1Department of general surgery, Kafr Elshikh General Hospital, Egypt

2,3Department of general surgery, Balteem Hospital, Egypt

Submission: November 14, 2018; Published: January 21, 2019

*Corresponding author: Ahmed Elsaady, Department of general surgery, Kafr Elshikh General Hospital, Kafr Elshiekh, Egypt

How to cite this article: Ahmed Elsaady*, Ragab Elsherbeny and Ashraf Elzaeem. Extensive Subcutaneous Emphysema after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, two Cases Reports. Open Access J Surg. 2024; 10(2): 555784. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2024.10.555784.

Abstract

Laparoscopic surgery has expanded its horizon tremendously. It has been the preferred approach in many operations. Massive subcutaneous emphysema is a rare unique complication of laparoscopic surgery. Here, we report two cases that developed progressive extensive subcutaneous emphysema after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On reviewing the literature, we found that the incidence ranges from 0.43% to 2.34%. There are many risk factors that have been implicated for its development including; pneumo-peritoneum of more than 200 minutes, and insufflation of CO2 at pressure more than 15mmHg, & PETCO2 more than 50 mmHg.

Clinically, subcutaneous emphysema produces an unusual crackling sensation on palpation and graded into four grades according to the severity. The patients should be monitored closely for any cardio-respiratory changes and positive pressure ventilation should be continued till normocarbia is established and signs of respiratory distress & upper airway obstruction are absent. Although conservative supportive measures and close follow up are the only needed strategy in most of cases, however surgical drainage may be beneficial in some case. This achieved either incisions (infraclavicular or submandibular) or tube drainage through different techniques.

Keywords: Subcutaneous emphysema; Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Complications of laparoscopy

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has expanded its horizon tremendously [1]. It has been the preferred approach in many operations [2]. Massive subcutaneous emphysema is a rare unique complication of laparoscopic surgery [3], that terrifies the patient& surgeon especially if the surgeon doesn`t have any experience in similar cases. We report here such a complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in two cases. Because of the increased rate of occurrence & their dangers, it is important that the surgeons should be familiar with these complications, their natural history, and their management [4].

Case Report

Case Report No 1

Female patient aged 32 years, presented with chronic calcular cholecyctitis, then laparoscopic cholecystectomy was decided and done 1.5 years ago. The operation was done via four ports with feasible trocar introduction. Although the dissection and removable of GB was passed smoothly, however straining of the patient and increased intraabdominal pressure to 20mmhg occurred and persisted for 10 minutes till it return to 15mmhg again.

The surgeon put a drain as a routine and closed the ports sites as usual and finished the procedure in about eighty minutes. One hour after recovery from anaesthesia progressive subcutaneous emphysema developed on the chest that rapidly progressed to the face with bilateral pre-orbital edema closing the eyes within several hours. Dyspnea with increasing pulse reaching 120b/m, as well as blood pressure (150/80 mmHg) and wide pulse pressure occurred with O2 saturation 92% at room. The patient admitted at ICU with O2 supply in semi-setting position and follow up. Chest X ray was normal. ABG was normal but done one day later. Then the condition settled and improved after three days of close follow up and discharged to room then to outpatient clinic after five postoperative days.

Case Report No 2

Female patient aged 38 years, presented for laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholelethiasis 1month ago. The procedure passed smoothly via 4 trocars with dissection & removal of GB and closure of the ports after putting a drain within about one hundred minutes. Nothing unusual reported during the operation except trouble in the anaesthesia machine making then anaesthesiologist changed it as well as the insufflator, where the pressure was noted to be high more than 18mmhg and persisted for sometimes. The patient immediately postoperative during recovery developed extensive progressive subcutaneous emphysema involving the whole chest and neck to the orbit without pneumothorax.

Tachycardia (100b/m), Dyspnea, were developed, Blood pressure was 130/80mmhg & O2 saturation was 94% at room. Chest x ray excluded pneumothorax. Close follow up with O2 supply in semi-setting position was done. Bilateral infra-clavicular incisions were done which gave temporary improvement. Then subcutaneous tube drainage from chest wall with massage and intermittent suction were also tried. The emphysema decreased on the third day and completely disappeared on the sixth day and discharged one day later.

Discussion

Epidemiology

Laparoscopy has surpassed and even replacing the open technique in many operations, with gaining benefits from their many advantages in terms of rapid recovery, less adhesions, less pain & length of hospital stays. However, post-operative subcutaneous emphysema is a unique complication, that particular to laparoscopy not to open surgery [5]. Although massive subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication of laparoscopy, but it is quite annoying one [6]. It was reported in both in intra and extra-peritoneal laparoscopy such as renal and colorectal surgery [7]. The incidence ranges from 0.43% to 2.34% [3]. However, it is thought to be more if carefully assessed. The incidence might be as high as 34% if assessed by chest X-ray& up to 56% by computed tomography [5]. Other authors reported as much as 77% of laparoscopy patients have grossly undetectable subcutaneous emphysema & 20% have findings on postoperative chest radiograph of pneumomediastinum [8].

Murdock et al. [4] reported incidence rates of 5.5% for hypercarbia, 2.3% for subcutaneous emphysema, and 1.9% for pneumothorax /pneumomediastinum following laparoscopy. Pneumothorax can be developed by extension of insufflate gas through congenital diaphragmatic channels into the pleural cavities and is reported as 0.03% [2]. Subcutaneous emphysema was reported to appear in the intraoperative as well as early and late postoperative periods (in the third day) [8].

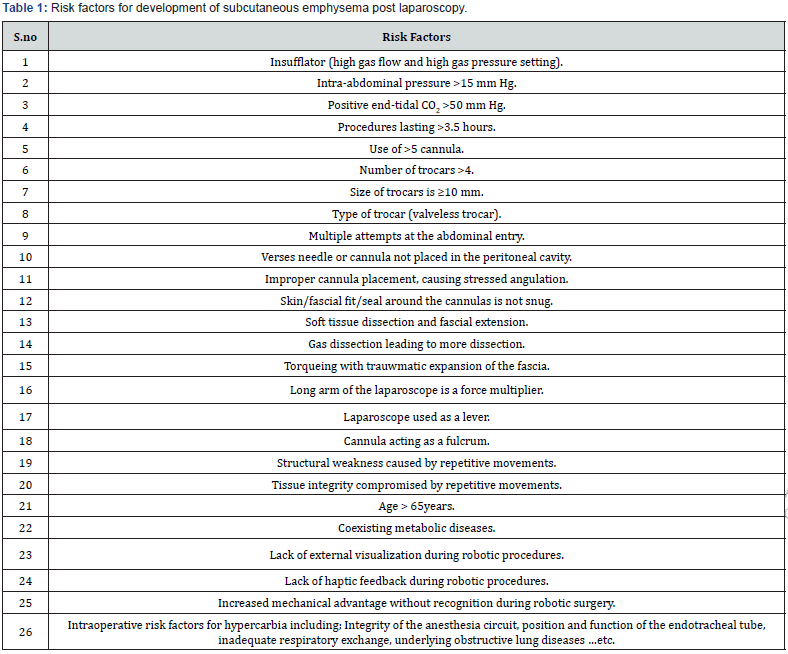

Risk factors

There are many risk factors that have been implicated for development of this complication [9] shown in Table 1. These include; prolonged surgery & pneumo-peritoneum of more than 200 minutes [10] and insufflation of CO2 at pressure ≥15mmHg [11]. Insufflator settings for pressure and flow rate influence insufflation dynamics, the amount of gas absorption or extraperitoneal extravasation with higher pressures, and flow rates contributing to the increased incidence of gas extravasation, noted as subcutaneous emphysema [12]. The total amount of gas used may or may not be related to the length of time of the procedure and may be more important than the length of time of the procedure [4]. Maximum positive end-tidal CO2 (PETCO2) more than 50mmHg is one predictor for its development [3].

Also, number of ports (six or more) [13], size and geometry of fascial incision to trocar size of entry site, snugness of fit between trocar and fascia, number of times the entry site is entered, amount of torqueing and pressure on entry sites, vectoring of the laparoscope, fulcrum effect between laparoscope and fascia, extraperitoneal dissection and methods of laparoscopy (video assisted or robotic) were also incriminated. Type of trocar used also may be a risk factor [14]. Recent articles citing use of a valve less trocar and dynamic pressure system (Air Seal; SurgiQuest, Milford, CT) showed a 16.4% rate of subcutaneous emphysema over 6.3 times the reported rate, a 3.9% rate of pneumomediastinum 2 times the reported rate, and a 0.9% complication rate of masked pneumothorax a rate 2.3 times the reported rate for a 21.24% total overall complication rate or 4.3 times the total reported rate [4].

Another risk factor is the age where older patients (specially more than 65years) are more prone to develop it, due to decrease in natural subcutaneous resistance [11]. Also, the patient BMI, coexisting metabolic diseases & tissue integrity can be real risk factors [15].

Pathophysiology

Dissection of the insufflate CO2 from the peritoneal cavity to the subcutaneous tissue may occur at the trocar site or through a defect in the diaphragm [16]. Intra-abdominal pressure of CO2 should therefore be monitored, since high pressures are associated with a higher incidence of subcutaneous emphysema. Following CO2 absorption into the blood, the gas is stored in visceral and muscle tissue, delaying prompt elimination via the lungs. Tracking of gas along fascial planes from port sites or through diaphragmatic defects occurred allowing increased absorption of carbon dioxide [2]. A latent pocket of carbon dioxide in the abdominal wall which disseminated only later, after mobilization of the patient; a gas leak from the anastomosis, later resealed; a small iatrogenic mucosal disruption, resulting in retroperitoneal air leak, settled spontaneously may also explain its development. On the other hand, an iatrogenic airway injury or a pneumothorax appears unlikely on account of clinical and radiological findings [17].

Dissection of the gas through the tissue depends on its structure, integrity, composition, architecture, morphology, tensile strength, and adherence to underlying structures. These tissue characteristics are affected by the pressure settings, pressure drop, volume, duration, and resistance to gas flow. With multiple repetitive movements of the laparoscope acting through a cannula, peritoneal separation can occur. The cannula acts as a fulcrum for the laparoscope (lever arm) to act as a class-one lever and force multiplier. The pivot point is the fascial entry site. The original peritoneal penetration site, then mechanically extended allowing gas extravasation into planes outside of the abdomen [4].

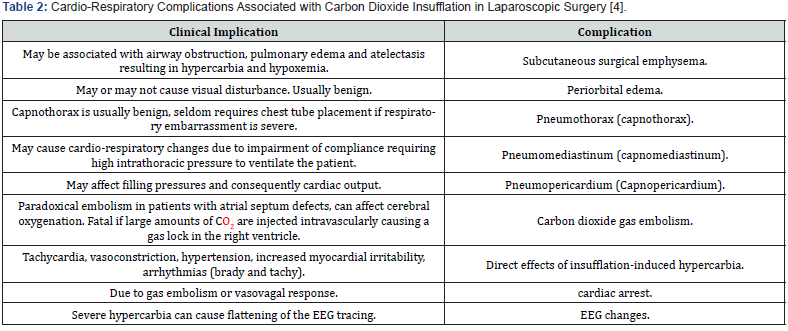

Anatomical connection between the cervical fascia and retroperitoneum was documented [17]. Notably, the soft tissues of the neck are divided into three main compartments by layers of cervical fascia. Two of these three spaces terminate at the upper thoracic spine; the visceral space, however, descends further, investing the trachea and oesophagus from the neck into the chest. Inferiorly, the visceral space extends with the oesophagus through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the retroperitoneal soft tissues [17]. Murdock notes an established link between preperitoneal insufflation and extensive dissection of retroperitoneal air [17]. Hypercarbia stimulates sympathetic nervous system, and hence the BP and HR increased. It also sensitizes the myocardium to catecholamines, predisposing to cardiac arrhythmias [18]. Later, several cardio-pulmonary complications may rapidly settle as in (Table 2).

Clinical Assessment

Post-laparoscopy subcutaneous emphysema varies from isolated area, confined in a small space to extravasation outside of the abdominal cavity extending into the labia, scrotum, legs, chest, head, and neck. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and retroperitoneal extravasation without pneumothorax have also been described during laparoscopic surgery and may be associated with prolonged hypercarbia [4]. Unilateral periorbital edema after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy was also reported [17]. Rarely, air progressing through the cervical fascia can extend along fascial planes to the face and periorbital region. Fortunately, periorbital emphysema subsides over the course of a few days without causing any visual disturbance [17].

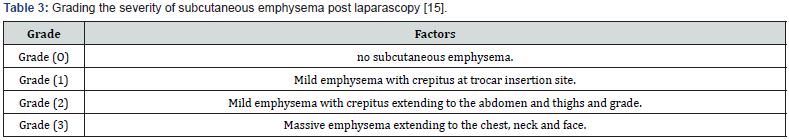

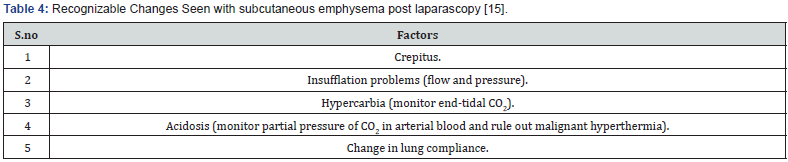

Clinically, subcutaneous emphysema produces an unusual crackling sensation on palpation as the gas in pushed through the tissues [15]. Severity of emphysema can be graded into four-point Grades as in Table 3; Grade O; no subcutaneous emphysema, Grade (1) Mild emphysema with crepitus at trocar insertion site, Grade 2; Mild emphysema with crepitus extending to the abdomen and thighs and grade 3; massive emphysema extending to the chest, neck and face [15].

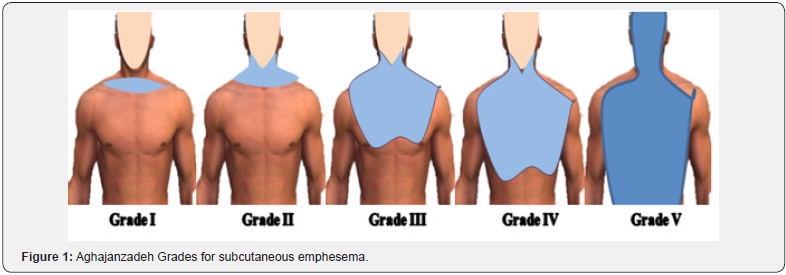

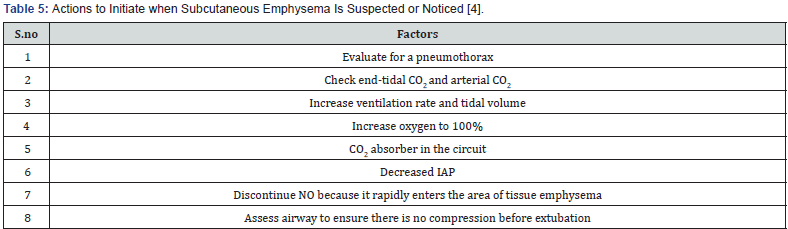

Another grading system for subcutaneous emphysema was also reported by Aghajanzadeh who divided it into five grades 19 as in Figure 1. Grade 1; involves the base of the neck only, grade (2) all the neck area, grade (3) subpectoralis major area, grade (4) chest wall and all the neck, while grade (5) involves chest wall, neck, orbit, scalp, abdominal wall, upper limbs, and scrotum [19]. Hypercarbia stimulates sympathetic nervous system, and hence the BP and HR increase. It also sensitizes the myocardium to catecholamines, predisposing to cardiac arrhythmias [18]. Cardiorespiratory complications may rapidly develop as in (Table 4).

Management

Early intraoperative detection is very important [1]. Anaesthesiologists must be aware of the risk factors to take precautions and detect emphysema in the early stages 1. Anaesthesia machines have option to measure VCO2. This parameter is useful to detect increases in CO2 production, which can be increased as a result of several conditions. These include inadequate ventilation, excessive CO2 production due to increased metabolism or release and external sources. During laparoscopic surgery, CO2 is absorbed by peritoneum; therefore, CO2 levels in blood are high. This is readily compensated by assisting expiration from the lungs as it has high aqueous solubility and diffusibility [20].

If alveolar ventilation is impaired, additional CO2 load is not cleared, resulting in hypercapnia and acidosis and EtCO2 elevation [20]. This is usually corrected by increasing minute volume as much as 30% [14]. If very high levels of EtCO2 are noticed, palpating the patients’ skin surface for emphysema and notifying the same to the surgeon is advisable. When subcutaneous emphysema appears, all the members of the team must be notified and start the management as in (Table 5).

A blood gas analysis is mandatory to evaluate the grade of acidosis, electrolytes disorders and gas interchange. Other potential events such as pneumothorax or air embolism must be ruled out. FiO2 of 100% must be delivered if oxygenation appears compromised [21]. The patient should be closely examined under the drapes intraoperatively even if the parameters of the ventilator are normal [21]. At the end of surgery, airway assessment before extubation must be performed. A direct laryngoscopy and a leak test should be considered as well as an airway exchange device must be kept ready for a potential airway compromise [22].

Tracheal extubation should be postponed if unsure of airway patency post-extubation [23]. Treatment is usually aiming at the underlined cause and respiratory support, while the air is gradually absorbed from interstitial tissues. The patients should be monitored closely for a longer duration in the postoperative period for any cardio-respiratory changes and positive pressure ventilation should be continued till normocarbia is established and signs of upper airway obstruction are absent [17]. However, in extensive cases, surgical intervention may be needed hoping for drainage of subcutaneous gas [24]. The drainage may be achieved by either incisions or tube drainage. Several manoeuvres have been reported [25]. Bilateral infra-clavicular incisions down to pectoralis fascia were recommended by Harlan as efficient procedure [26], while others recommended submandibular incisions [27]. On the other hands a lot of varieties for tube drainage have been reported. A trochar-type chest tube [26], wide angiocatheter (14G) & central venous catheter [28] are also reported to be efficient.

Jackson-Pratt drain or 12Fr Seldinger drain administrated in the tract dissected & then placed on gentle suction to ensure tube patency & air resorption was described [26]. Srinivas et al. [5] described a modified microcatheter & active compressive massage with the face downward & arms upward toward the catheter to facilitate the drainage [27]. Liposuction as efficient method for gas drainage was reported [28]. Unfortunately, there is no reliable comparison study, to identify the best method; neither we have any large series study published about possible complications of each method [29]. Larger studies are needed to come to safe conclusions [29].

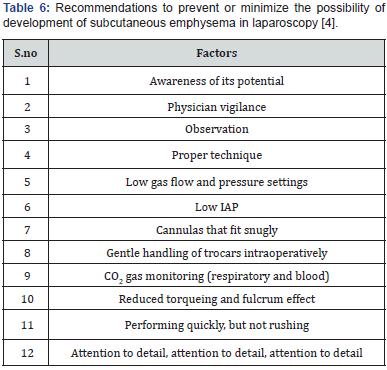

However, the likelihood for development of subcutaneous emphysema in laparoscopy can be diminished by the following recommendations [4] shown in Table 6; awareness of its potential; physician vigilance; attention to detail regarding abdominal entry; monitoring insufflator settings for pressure, flow rate, and volume of gas with alarm settings; quickness, but not rushing, to complete the procedure (because length of procedure and gas consumption relate to the condition); reduce the number of attempts to enter the abdomen; have a snug trocar skin condition; test for correct. Also, look at and feel the skin around the cannula insertion sites, perform the surgery quickly but not hurried, and, finally-attention to detail [4].

Review the Two Cases Reports

The alarming factors in both cases were the increased intra-abdominal pressure more than 15mmHg and absence of the awareness and experience of the operative team with this complication. In the two cases the progress of the emphysema is outmost in the first 24hours and decreased on the third day, while completely relived after 1week. Surgical drainage either by infra-clavicular incision or by tube provided only temporary improvement. Awareness & attention to detail seem to be important factor especially in prevention, early detection and proper management a s well as minimizing the panic feeling of the patients and their relatives with massive subcutaneous emphysema.

Conclusion

Massive subcutaneous surgical emphysema is a rare complication after laparoscopic surgery. Many risk factors have been incriminated including; pneumo-peritoneum of > 200 minutes10 and insufflation of CO2 at pressure ≥15mmHg, maximum positive end-tidal CO2 (PETCO2) > 50mmHg. Most of these factors are preventable. Early detection is important. The patients should be monitored closely for any cardio-respiratory changes and positive pressure ventilation should be continued till normocarbia is established and signs of respiratory distress & upper airway obstruction are absent. Although conservative supportive measures and close follow up are the only needed strategy in most of cases, however surgical drainage may be beneficial in some case. This is achieved either incisions or tube drainage through different techniques. The superiority of each technique is debatable, need more studies.

References

- Sood J (2014) Advancing frontiers in anaesthesiology with laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 20(39): 14308-14309.

- Saeed S, Godwin O, Adu AK, Ramcharan A (2017) Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema after successful laparoscopic supra-cervical hysterectomy. J Surg Case Rep 2017(7): rjx146.

- Critchley LA, Ho AM (2010) Surgical emphysema as a cause of severe hypercapnia during laparoscopic surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care 38(6): 1094-1100.

- Ott DE (2014) Subcutaneous Emphysema-Beyond the Pneumoperitoneum. JSLS 18(1): 1-7.

- Jones A, Pisano U, Elsobky S, Watson AJ (2015) Grossly delayed massive subcutaneous emphysema following laparoscopic left hemicolectomy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 6C: 277-279.

- Baron PW, Ben Youssef R, Ojogho ON, Kore A, Baldwin DD (2012) Morbidity of 200 consecutive cases of hand-assisted laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies: A single-center experience. J Transplant 2012: 121523.

- Nakajima K, Kai Y, Yasumasa K, Nishida T, Ito T, et al. (2006) Subcutaneous emphysema along cutaneous striae after laparoscopic surgery: a unique complication. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 16(2): 119-121.

- Coronil ÁB, Sanchez Cañete AM, Bartakke AA, Fernández JG, García AI (2016) Life-threatening subcutaneous emphysema due to laparoscopy. Indian J Anaesth 60(4): 286-288.

- Herati A, Atalla M, Rais Bahrami S, Andonian S, Vira M, et al. (2009) A new valve-less trocar for urologic laparoscopy: initial evaluation. J Endourlol 23(9): 1535-1539.

- Horstmann M, Horton K, Kurz M, Padevit C, John H (2013) Prospective comparison between the AirSeal® System valve-less Trocar and a standard Versaport Plus V2 Trocar in robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Endourol 27(5): 579-582.

- Saggar VR, Singhal A, Singh K, Sharma B, Sarangi R (2008) Factors influencing development of subcutaneous carbon dioxide emphysema in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 18(2): 213-216.

- Murdock CM, Wolff AJ, Geem TV (2000) Risk factors for hyper-carbia, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum during laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol 95(5): 704-709.

- Giorgakis E, Fernandez Diaz S (2013) Diffuse Subcutaneous Emphysema after Transperitoneal Laparoscopic Donor Nephrectomy, Hippokratia 17(1): 94.

- Tan PL, Lee TL, Tweed WA (1992) Carbon dioxide absorption and gas exchange during pelvic laparoscopy. Can J Anaesth 39(7): 677-681.

- Saini S, Agrawal N (2015) Massive subcutaneous emphysema following laparoscopic nephroureterectomy: An unusual presentation. Indian J Anaesth 59(6): 389-390.

- ASM Moosa, M Baharul Islam, Shahina Akther, M Latifur Rahman, Nazim Uddin Ahmed (2008) Massive Subcutaneous Emphysema during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. The Journal of Teachers Association 21(1): 77-79.

- Jaydev Sarma (2011) Unilateral Periorbital and Cervical Subcutaneous Emphysema Following Extraperitoneal Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy. The Open Anesthesiology Journal 5: 1-4.

- Srivastava A, Niranjan A (2010) Secrets of safe laparoscopic surgery: Anaesthetic and surgical considerations. J Minim Access Surg 6(4): 91-94.

- Aghajanzadeh M, Dehnadi A, Ebrahimi H, Fallah Karkan M, Khajeh Jahromi S, et al. (2015) Classification and Management Of Subcutaneous Emphysema: A 10-Year Experience. Indian JSurg 77(Suppl 2): 673-677.

- Valenza F, Chevallard G, Fossali T, Salice V, Pizzocri M, et al. (2010) Management of mechanical ventilation during laparoscopic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 24(2): 227-241.

- Manchanda G, Bhalotra AR, Bhadoria P, Jain A, Goyal P, et al. (2007) Capnothorax during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia 51: 231-233.

- Yagihashi Y, Okinami T, Fukuzawa S (2009) Case of pharyngeal emphysema with airway obstruction during retroperitoneal laparoscopic nephroureterectomy. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 100(4): 540-544.

- Chandra A, Clarke R, Shawkat H (2014) Intraoperative hypercarbia and massive surgical emphysema secondary to transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS). BMJ Case Rep pii: bcr2013202864.

- Sucena M, Coelho F, Almeida T, Gouveia A, Hespanhol V (2010) Massive subcutaneous emphysema--Management using subcutaneous drains. Rev Port Pneumol 16(2): 321-329.

- O'Reilly P, Chen HK, Wiseman R (2013) Management of extensive subcutaneous emphysema with a subcutaneous drain. Respirol Case Rep 1(2): 28-30.

- Srinivas R, Singh N, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN (2008) Management of extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum by micro-drainage: Time for a re-think? Singapore Med J 48(12): e323-e326.

- Vijayalakshmi AM, Vel MT (2003) Subcutaneous Emphysema. Indian Pediatr 11: 1092-1093.

- Lloyd MS, Jankowksi S (2009) Treatment of Life-Threatening Surgical Emphysema with liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg 123(2): 77e-78e.

- Aslanidis Theodoros, Kontos Athanasios (2017) Surgical Treatment of Subcutaneous Emphysema. In Which Cases? Journal of Surgery and Emergency Medicine 1(2): 12.