Positioning of Sophono (Otomag Alpha 2) Bone Conduction Transcutaneous Device in Subjects Undergoing Radical Mastoidectomy

Mammarella F1*, Zelli M1, Varakliotis T1,2, Eibenstein A2, Pianura CM1 and Bellocchi G1

1ENT Department, San CamiHo Forlanini Hospital, Italy

2Department of Applied Clinical Sciences and Biotechnology (DISCAB), L'Aquila University, Italy

Submission: January 27, 2018; Published: February 16, 2018

*Corresponding author: Fulvio Mammarella, ENT Department, San Camillo Forlanini Hospital, Italy, Tel: 3336954667; Email: fulvio.mammarella@hotmail.it

How to cite this article: Mammarella F, Zelli M, Varakliotis T, Eibenstein A, Pianura CM, Bellocchi G. Positioning of Sophono (Otomag Alpha 2) Bone Conduction Transcutaneous Device in Subjects Undergoing Radical Mastoidectomy. Open Access J Surg. 2018; 8(2): 555732. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2018.08.555732

Introduction

The first electro acoustic hearing aid (ha) in history is dated 1880 by Alexander Graham Bell (made for his wife Mabel Hubbard deaf from the age of five years old from complications of an infection). The technological evolution begun in the 50s allowed its miniaturization and ubiquitous diffusion, however some subjects must use a different type of ha (atresia auris, inflammatory stenosis of the CUE, skin diseases, degree of hearing loss, etc.). Starting from the identification of the bone integration, the work of Dr. Branemark in the '60s, numerous medical applications have been developed, among which the introduction of bone conduction device, commonly called BAHA by the name of the progenitor, is the first in the audiological field. The modern advances of the otologic endoscopic surgery and / or use of Mesna have not eradicated the secondary use of open technique in case of cholesteatoma, residual or recurrent (about 20-25%) [1,2]. Until a few years ago the acoustic rehabilitation of these cavities was problematic, we describe our experience in the placement of passive transcutaneous bone conduction device in two subjects undergoing radical mastoidectomy for recurrence of cholesteatoma.

Materials and Methods

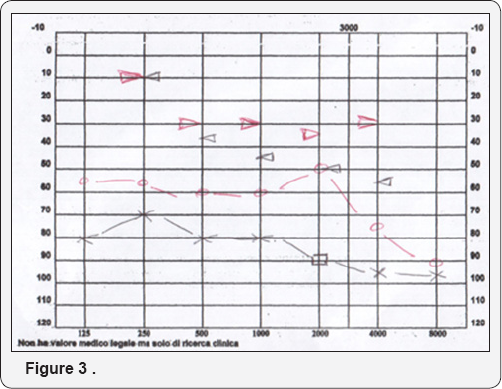

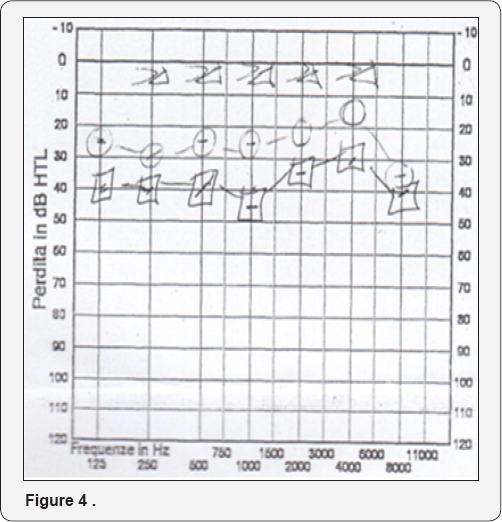

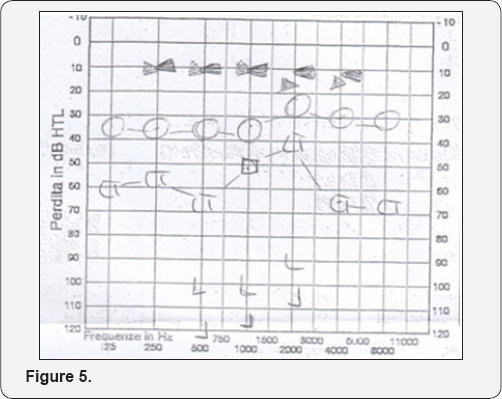

Two subjects, respectively a man and a woman, followed by our otological surgery center and suffering from residual mixed hearing loss after radical mastoidectomy, were selected for a preliminary result evaluation by placement of a passive transcutaneous prosthesis on an elastic band (Rod test) based on the audiometric profile. Both underwent multiple otologic surgery, first with conservative technique CWU, then demolishing one, for recurrent cholesteatoma, diagnosed in early adulthood. The first candidate, a 55-years-old man after undergoing a right CWU on a different acoustic centre about 20 years ago, had arrived at our emergency room affected by meningitis of otogenic secondary nature to recurrence of cholesteatoma for which it was necessary to perform a radical mastoidectomy with repair of bone breach (Figures 1 & 2) (it is also possible to visualize the positioning of sophono prosthesis). After three years, the subject, asymptomatic with the perfectly reoxified breach, presented bilateral mixed hypoacusia, unexpectedly more relevant on the left by the presence of a chronic glue ear (Figure 2), for which the patient refused the surgical indication. The bone loss showed mild-to-moderate hypoacusis with a maximum loss of 35 dbHL in the best ear (Figure 3). The second candidate was a 51-years-old woman first operated 8 years ago for right cholesteatoma and submitted 4 years ago to revision with radical mastoidectomy for recurrent cholesteatoma. The tonal profile showed a mixed loss, slightly more pronounced on the left, with normoacusis via bilateral bone (Figure 4). Six months after surgery, secondary left acoustic deterioration of chronic catarrhal otitis worsening in medical therapy resulted in a marked worsening of the left threshold with difficulty in spatial and vocal discrimination (Figure 5). Informed of the right bone device option, she underwent a positive test with a soft band for which she decided to undergo its placement.

Discussion

The first placement of a titan screw in the extraoral region for the implantation of a hearing aid is dated 1977. The candidates were limited to patients with conductive hearing loss, both adults and children [3], with a mild loss of bone conduction (<35 dB HL on the frequencies 500-4000). Over the last few years the original indication has also been extended to subjects with mixed hearing loss [4,5] or, more recently, singled side deafness (SSD) [6,7] and even pure neurosensory hearing losses [8] with loss within 45 db HL (in these last two cases with less benefit). Despite its simplicity of positioning and the objective advantages described in years of scientific literature, its diffusion has been limited for the problems related to the management of the surgical incision and above all the aesthetic imperfection [9], limiting its application to the malformation pathologies [10].

The recent introduction of transcutaneous devices, initiated with the first otomag model, has cancelled this fear [11]. However, due to its recent introduction, some doubts still exist on its application in particular categories (paediatric one) for the possibility of generating alterations of the cutanous layer [12] . Sophono device is made up by an external part (the sound processor) and an internal one (a twin magnet). The surgical technique is very easy, complete safe and can be performed with a local or a brief general anaesthesia, especially in children. A muscular-coetaneous flap is elevated for exposure the temporal bone. The correct position on bone of device is defined using a template then the location is drilled. For a correct placement the depth of drilling can be test using a false twin magnet also called dummy. Finally the magnet is stabilizing with five bone screw.

The cavities of radical mastoidectomy often have heterogeneous functional results, representing a dilemma for the acustic rehabilitation due to the impossibility to the positioning of conventional prosthesis. Among the AMEI, the vibrant sound bridge offers the possibility of acoustic rehabilitation through its positioning on the round window [13] in an extremely heterogeneous group of situations: transmission or mixed hearing loss due to the presence of congenital oxycular defects [13] , diseases of the middle ear [14], atresia of the oval window [15], post-petrosectomy [16]. Similarly, the application of bone conduction devices in the presence of mixed postoperative hearing loss has already been described in subjects subjected to CWD [17] and radical mastoidectomy as well [18] both to improve sound localization (pseudo-stereo) and the acoustic rehabilitation still of percutaneous type. An audio logical criterion for the selection of the type of aid was defined by Mojallah [19] who defined the threshold for the bone at 35 dbHL as the maximum limit for the positioning of BAHA prosthesis. The simplicity of positioning, the absence of imperfections and the reduced size of the magnet makes it an optimal solution for acoustic rehabilitation even in subjects undergoing radical mastoidectomy; however the absence of cortical bone makes it necessary an abnormal postero-superior positioning in order to find sufficient bone for the magnet housing (Figure 2). Similar studies are published in the literature (positioning of sophono prosthesis in subjects subjected to subtotal petrosectomy with closure of the external auditory canal [20]) nevertheless this is the first case study in subjects undergoing radical mastoidectomy. Clinically, both cases selected and submitted to the procedure report an optimal acoustic rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Haring loss, more frequently mixed, following radical mastoidectomy, is a frequent and disabling condition. The impossibility of positioning a traditional ha has almost always prevented the acoustic rehabilitation of these subjects. The introduction of new AMEI acoustic aids, and specifically the vibrant sound bridge, has opened a new rehabilitation threshold. In patients with preserved bone or mild hearing loss (within 3540 db hl on the 500-4000 frequencies) the positioning of a BAHA prosthesis is a valid option, better if percoutaneus type. Ours is the first acoustic rehabilitation report in the cavity of radical mastoidectomy with sophono device.

References

- Stew BT, Fishpool SJ, Clarke JD, Johnson PM (2013) Can early second- look tympanoplasty reduces the rate of conversion to modified radical mastoidectomy? Acta Otolaryngol 133(6): 590-593.

- Crowson MG, Ramprasad VH, Chapurin N, Cunningham CD, Kaylie DM (2016) Cost analysis and outcomes of a second-look tympanoplasty- mastoidectomy strategy for cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 126(11): 2574-2579.

- Liu CC, Chadha NK, Bance M, Hong P J (2013) The current practice trends in paediatric bone-anchored hearing aids in Canada: a national clinical and surgical practice survey. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 42: 43.

- Siegert R, Kanderske J (2014) Semi-implantable transcutaneous bone conduction hearing devices. HNO 62(7): 502-508.

- Mclean T, Pai I, Philipatos A, Gordon M (2017) The Sophono bone- conduction system: Surgical, audiologic, and quality-of-life outcomes. Ear Nose Throat J 96(7): E28-E33.

- Snapp H, Angeli S, Telischi FF, Fabry D (2012) Postoperative validation of bone-anchored implants in the single-sided deafness population. Otol Neurotol 33(3): 291-296.

- Hougaard DD, Boldsen SK, Jensen AM, Hansen S, Thomassen PC (2017) A multicenter study on objective and subjective benefits with a transcutaneous bone-anchored hearing aid device: first Nordic results. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 274(8): 3011-3019.

- Hartland SH, Proops DW (1996) Bone anchored hearing aid wearers with significant sensorineural hearing losses (borderline candidates): patients' results and opinions. J Laryngol Otol Suppl 21: 41-46.

- Siau RT, Dhillon B, Siau D, Green KM (2016) Bone-anchored hearing aids in conductive and mixed hearing losses: why do patients reject them? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273(10): 3117-3122.

- Mazita A, Fazlina WH, Abdullah A, Goh BS, Saim L (2009) Hearing rehabilitation in congenital canal atresia. Singapore Med J 50(11): 1072-1076.

- Shin JW, Kim SH, Choi JY, Park HJ, Lee SC, et al. (2016) Surgical and Audiologic Comparison between Sophono and Bone-Anchored Hearing Aids Implantation. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 9(1): 21-26.

- Marsella P, Scorpecci A, Dalmasso G, Pacifico C (2015) First experience in Italy with a new transcutaneous bone conduction implant. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 35(1): 29-33.

- Colletti L, Mandala M, Colletti V (2013) Long-term outcome of round window Vibrant Sound Bridge implantation in extensive ossicular chain defects. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 149(1): 134-141.

- Claros P, Pujol Mdel C (2013) Active middle ear implants: Vibroplasty™ in children and adolescents with acquired or congenital middle ear disorders. Acta Otolaryngol 133(6): 612-619.

- Zhao S, Gong S, Han D, Zhang H, Ma X, et al. (2016) Round window application of an active middle ear implant (AMEI) system in congenital oval window atresia. Acta Otolaryngol 136(1): 23-33.

- Linder T, Schlegel C, DeMin N, van der Westhuizen S (2009) Active middle ear implants in patients undergoing subtotal petrosectomy: new application for the Vibrant Sound bridge device and its implication for lateral cranium base surgery. Otol Neurotol 30(1): 41-47.

- Gluth MB, Friedman AB, Atcherson SR, Dornhoffer JL (2013) Hearing aid tolerance after revision and obliteration of canal wall down mastoidectomy cavities. Otol Neurotol 34(4): 711-714.

- Schupbach J, Kompis M, Hausler R (2004) Bone anchored hearing aids (B.A.H.A.) Ther Umsch 61(1): 41-46.

- Mojallal H, Schwab B, Hinze AL, Giere T, Lenarz T (2015) Retrospective audiological analysis of bone conduction versus round window vibratory stimulation in patients with mixed hearing loss. Int J Audiol 54(6): 391-400.

- Magliulo G, Turchetta R, Iannella G, Valperga di Masino R, de Vincentiis M (2015) Erratum to: Sophono Alpha System and subtotal petrosectomy with external auditory canal blind sac closure. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 272(9): 2191.