Preoperative Prognostic Features of Pancreatic Head Adenocarcinoma

Kelsey Hinther1, Sanji Ali1, Jack Spiers2, Bill Taylor3, Roman Bacchus4, Ismail Peer4, Mahmoud Soliman5 and Yigang Luo1,5,6*

1College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

2Department of Radiology, Regional Hospital, Canada

3Department of Anesthesiology, Regional Hospital, Canada

4Department of Gastroenterology, Regional Hospital, Canada

5Department of Surgery, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

6Department of Surgery, Regional Hospital, Canada

Submission: December 13, 2016; Published: January 04, 2017

*Corresponding author: Yigang Luo, Royal University Hospital, Ellis Hall, Rm 161, 103 Hospital Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada S7N 0W8, Email: yil872@mail.usask.ca

How to cite this article: Kelsey H, Sanji A, Jack S, Bill T, Roman B et al. Preoperative Prognostic Features of Pancreatic Head Adenocarcinoma. Open Access J Surg. 2017; 2(1): 555578. DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2016.02.555578

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to define the preoperative prognostic features in pancreatic cancer patients of Whipple procedure.

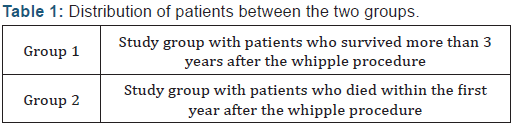

Methods: The medical records of pancreatic head adenocarcinoma patients who underwent Whipple procedure by a single surgeon from 2003 -2012 were reviewed. The cases were retrogradely analyzed in 2 groups: Group 1 (n=9) comprised of patients who lived more than 3 years, and Group 2 (n=13) comprised who died within 1 year following the surgery. Clinical data were collected by chart review, including demographic, histopatho-logic, preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative findings. Anova microsoft excel sta-tistic analysis was performed on the recorded data.

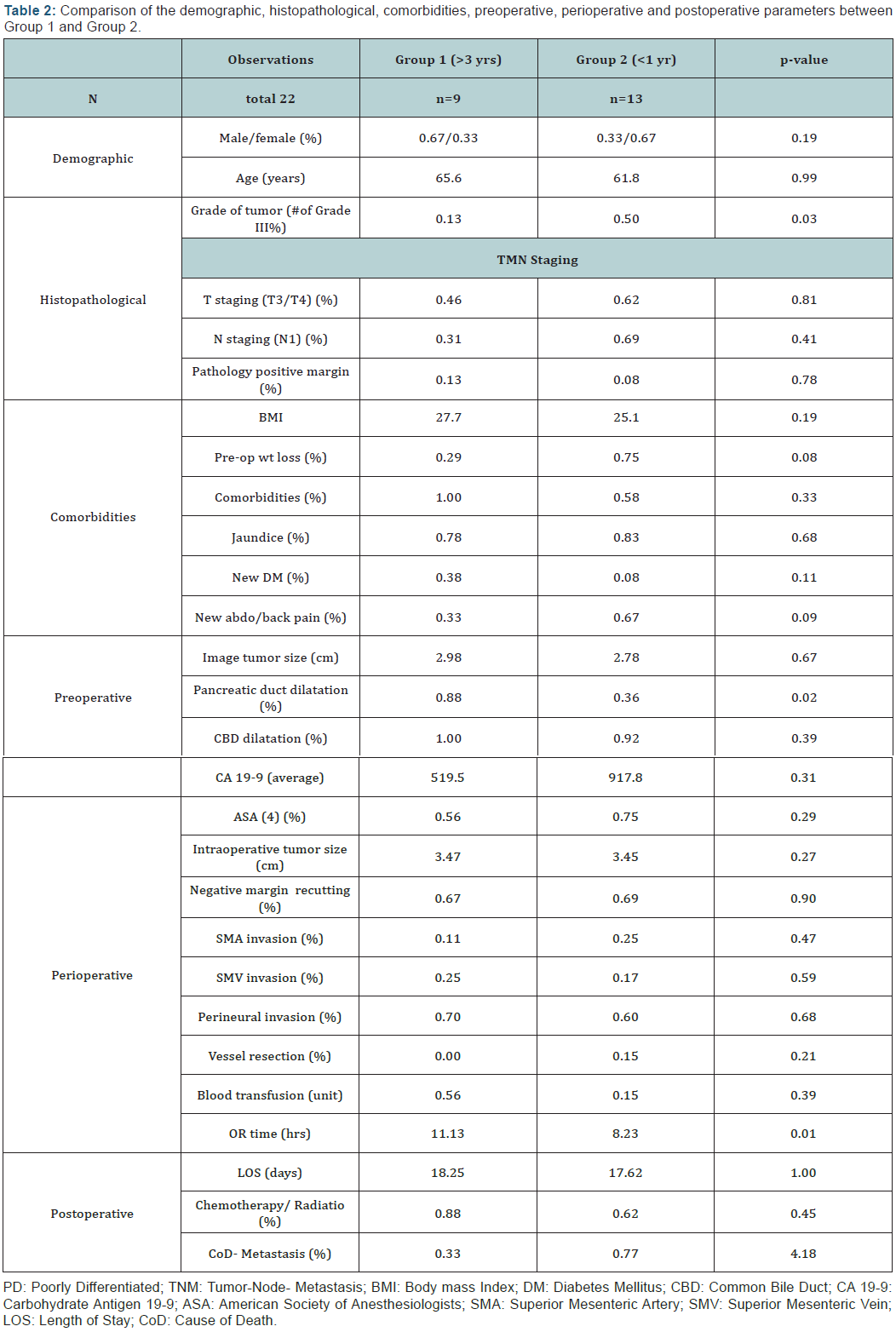

Result: Patients in Group 2, who survived less than 1 year following surgery, had statis-tically significant more poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and less dilatation of the pancreatic duct. These patients were more often to have preoperative abdominal/back pain, weight loss and higher level of CA19-9, as compared with those of Group 1 pa-tients. Both groups showed most patients died due to metastatic disease.

Conclusion: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is not a homogeneous disease. It is possible to find preoperative prognostic features for more appropriate management. With better pre-operative stratification, the care for these patients could be more individualized, and lead to better outcome.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the Western World, following lung, colorectal and breast cancer [1-9]. Unlike these cancers, the mortality rates for pancreatic cancer remain relatively unchanged [10]. Without treatment, the overall 5-year survival rate is less than 10% [1,7-9,11]. Surgical resection is the only therapeutic treatment to achieve long-term survival [2,5,8,9,12]. The majority of patients have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, thus only 10-20% of patients are considered candidates for curative resection [1,4,8,9]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as Whipple procedure, is the surgical treatment choice in patients who have resectable tumors located at the head of the pancreas, or regions adjacent to the head of the pancreas [10].

Although the survival rates following surgery have improved over last few decades, the prognosis following surgery remains poor, with an overall five-year survival ranging between 10 to 25% [12]. Several studies have analyzed the determinants of short-term and long-term survival rates in post-resection pancreatic cancer patients, but the results have been inconsistent [1,2]. Finding preoperative prognostic features in clinical resectable patients will help to triage patients for appropriate treatment. The purpose of this study is to determine the preoperative prognostic factors influencing short-term and long-term survival rates in pancreatic cancer patients who were all resectable on preoperative clinical staging according to NCCN guideline.

Methods

Twenty-two of 87 Whipple procedures performed by a single surgeon in Windsor, Ontario, Canada between March 2004 and October 2012 were pathology confirmed pancreatic head adenocarcinoma and survived for either less than one year or more than 3 years after the surgery. The patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 comprised of 9 patients who lived more than 3 years, and Group 2 comprised of 13 patients who died with-in 1 year, following the surgery. Potential prognostic factors abstracted in this study included demographic, histopathologic, preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative factors. The primary variable analyzed in this study was survival time after surgery. Survival time was defined from the time of surgery to death due to pancreatic cancer-related complications. Anova microsoft excel statistic analysis was performed on the recorded data.

Results

All 22 patients were preoperatively diagnosed and classified as resectable pancreatic cancer according to NCCN pancreatic cancer guideline. Indeed, all of these patients had radical resection by means of Whipple procedure. Our results suggested that most observation data were not statistically significant. However, pathological differentiation and pancreatic duct dilatation were found statistically significant different between the two groups, while preoperative weight loss, abdominal/ back pain and CA19-9 level were trending more often in Group 2, those survived less than one year after the surgery (Tables 1 & 2).

Discussion

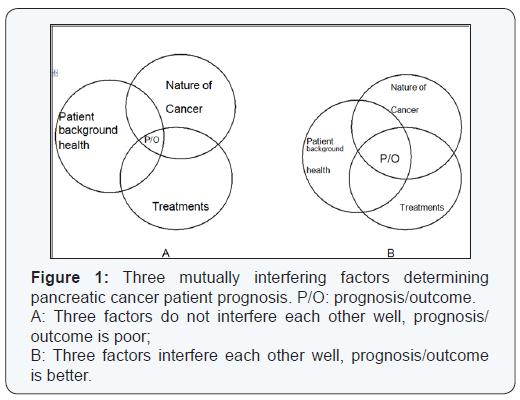

Pancreatic cancer like many other malignancies is a systemic disease. It affects individual patient differently based on many variables (Figure 1), including factors associated with tumor aggressiveness, clinical background condition of the patient, and the scope of the treatment used, amongst others [1-3]. In order to determine the optimal treatment strategy that can be of most beneficial for each individual patient, this study was to investigate the variables that were responsible for the prognosis of pancreatic cancer, particularly those in the preoperative period. For many years, Whipple procedure has been the choice of surgical treatment for early-staged tumors [4]. However, systemic therapy including adjuvant chemoradiational therapy, immunotherapy is playing roles for patient long-term survival. Neo-adjuvant therapy before surgery has also been becoming an important therapeutic strategy in the modern management of pancreatic cancer patients [6].

This study reviewed various factors associated with survival time in pancreatic cancer treatment. Data analysis showed no statistically significant differences in patients’ background health and oncological treatments including surgery and chemo/ radiation therapies between the two groups. The Whipple procedures for all patients performed by a single surgeon kept surgical treatment relatively identical to each patient. Therefore, the prognosis should be reasonably believed to be depending on the pancreatic cancer itself. A cancer causing poor prognosis should be in one of two possible situations:

- The cancer was in late stage when it was found, thus it caused the patient’s death in short time;

- The cancer was still in relatively early stage, however, in very aggressive nature, i.e. developing very fast and killing the patient in short time.

All our patients were clinically staged as resectable per NCCN guideline, with similar size and lymph node involvement. It is suggested that the difference in prognosis was most likely caused by the different natures of the cancer, instead of purely pathological staging, between the groups. The main findings in this study were poorly differentiated tumors and less dilatation of the pancreatic duct predicted reduced post-operative survival time. Pre-operative weight loss, higher level of CA 19-9, and new abdominal/back pain were also more prevalent in short survival group. Group 2, the patients who survived less than one year after surgery had more poorly differentiated tumors on pathology, denoting more aggressive tumors in these patients. This group also had fewer patients with pancreatic duct dilatation. Possible explanation might be that a more aggressive cancer presented only for a shorter period of time with not enough time causing chronic pancreatic duct obstruction and thus dilatation.

Justification for terminology

According to genomic analysis, there are 4 different molecular subtypes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma:

- Squamous;

- Pancreatic progenitor;

- Immunogenic; and

- Aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine (ADEX) that correlate with histopathological characteristics [14]. Each subtype develops from different genetic mutation pathways and carries different prognosis. Obviously, cancers in Group 1 and Group 2 were not homogeneous in nature/aggressiveness, even though no genetic testing was conducted.

Most of patients, who died, died of metastasis that was not identified with preoperative imagings. This microscopic image unidentifiable pre-operative metastasis should be considered as phenotype of more aggressive nature of cancer, which were more consistent in Group 2, where preoperative weight loss, abdominal/back pain, and higher levels of CA 19-9 were more common. Despite no statistical significance obtained these few variables might help to identify more aggressive cancer in group 2 patients, in addition to the above mentioned preoperative pancreatic duct non-/less dilatation.

Only 15%-20% of pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed with a resectable tumor, while 45%-50% are diagnosed with metastatic disease [11]. A tumor with no arterial tumor contact (celiac axis CA, superior mesenteric artery SMA, common hepatic artery) and no contact with superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein (PV) or ≤ 180⁰ contact with no vein contour irregularity is considered resectable [12]. A tumor with distant metastasis or unreconstructible SMV/PV, or pancreatic head tumor with ≥ 180⁰ encasement of the SMA or CA, or pancreatic body or tail tumor with ≥ 180⁰ encasement of the SMA or CA or tumor contact with CA and aortic involvement, is considered unresectable [12]. Tumor staging is also important to decide whether to treat with curative resection or neoadjuvant therapy. Group 2 patients all died within one year after the surgery. In other words, surgery did not benefit these patients. On the other hand, Whipple procedure is a lengthy and extensive surgery.

Advances in medical and surgical technology have reduced its mortality rates to less than 5%, but morbidity rates continue to be high up to 30%-60% [5-8,10]. Postoperative complications, include delayed gastric emptying, infections, intra-abdominal abscess and abdominal hemorrhage, etc [1,5,9,10]. These complications increase hospital stay, and delay postoperative recovery and further adjuvant therapy [5,10]. Whipple procedure also has an increased risk of perioperative and postoperative in hospital mortality [1,5]. It is important to stratify the patients preoperatively to prevent patients like in Group 2 from this surgery which is futile in treatment and non-economical in resources. Non-surgical treatment may be more appropriate for this group of patients. Neo-adjuvant therapy could render about one-third of borderline resectable cancer cases to resectable, making surgical resection possible [13]. Newly emerging Nano Knife (Irreversible Electroporation) treatment was used to treat non-resectable pancreatic cancer patients with good results [14].

Appropriate triage of patients is undertaken preoperatively, the valuable operating time and other resources could be used more efficiently, while the patients would be treated more effectively. Additionally, an interesting finding was that almost all deceased patients at the time of the study had died of metastasis (liver or lung metastasis), seldom from local recurrence. Thus, surgery is not the only treatment for pancreatic cancer, despite being the only treatment option leading to long-term survival. This finding warrants effective and timely systemic therapy and a multidisciplinary approach. The limitations of this study are its small sample size and long sampling period. However, overall the findings in this preliminary study were still informative and are worth further investigation. Larger sample size with multiinstitution involvement study in the future is warranted to elucidate the findings and discover more clues for preoperative treatment triage.

Conclusion

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is not a homogenous disease. With better preoperative stratification, individualized patient care would lead to a better outcome. Moreover, clinical management could be more efficient, economically beneficial, while reducing surgical wait time and sparing selected patients from futile surgery. Patient death was found often due to metastatic disease. Therefore, surgery seems not enough for pancreatic cancer treatment even though it is the only one leading to long-term survival. Early systemic cancer control (by neo-adjuvant therapy) might be important to facilitate longterm survival.

References

- Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC (2003) Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 237(1): 74-85.

- Eloubeidi MA, Desmond RA, Wilcox CM, Wilson RJ, Manchikalapati P, et al. (2006) Prognostic factors for survival in pancreatic cancer: a population based study. Am J Surg 192(3): 322-329.

- Papadoniou N, Kosmas C, Gennatas K, Polyzos A, Mouratidou D, et al. (2008) Prognostic factors in patients with locally advanced (unresectable) or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A retrospective analysis. Anticancer res 28(1B): 543-550.

- Peixoto RD, Speers C, McGahan CE, Renouf DJ, Schaeffer DF, et al. (2015) Prognostic factors and sites of metastasis in unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med 4(8): 1171-1177.

- Corsini MM, Miller RC, Haddock MG, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, et al. (2008) Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy for pancreatic carcinoma: The mayo clinic experience (1975-2005). J Clin Ooncol 26(21): 3511-3516.

- Fogelman DR, Overman MJ, Varadhachary GR, Fortuno M (2008) Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for resectable and borderline pancreatic cancer. Applied Cancer Research 28(4): 127-133.

- Luo J, Xiao L, Wu C, Zheng Y, Zhao N (2013) The Incidence and Survival Rate of Pop-ulation-Based Pancreatic Cancer Patients: Shanghai Cancer Registry 2004-2009. PLoS ONE 8(10): 1-7.

- Hackert T, Buchler MW, Werner J (2011) Current state of surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Cancers 3(1): 1253-1273.

- Herreros-Villanueva M, Hijona E, Cosme A, Bujanda L (2012) Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 18(14): 1565-1572.

- Klinkenbijl JHG, Jeekel J, Schmitz PI, Rombout PA, Nix GA, et al. (1993) Carcinoma of the pancreas and periampullary region: palliation versus cure. Br J Surg 80(12): 1575-1578.

- Speer AG, Thursfield VJ, Torn-Broers Y, Jefford M (2012) Pancreatic cancer: surgical management and outcomes after 6 years of follow-up. Med J Aust 196(8): 511-515.

- Marius Distler, Felix Rückert, Maximilian Hunger, Stephan Kersting, Christian Pilarsky, et al. (2013) Evaluation of survival in patients after pan-creatic head resection for ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Surgery 13(12): 1-8.

- Stauffer JA, Rosales-Velderrain A, Goldberg RF, Bowers SP, Asbun, HJ (2013) Comparison of open with laproscopic distal pancreatectomy: a single institution’s transition over a 7-year period. HPBD 15(2): 149- 155.

- Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, et al. (2016) Genomic analyses identify molecular sub-types of pancreatic cancer. Nature 531(7592): 47-52.