Multiple sclerosisPrevalence and Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depression Among Pregnant Women

Afusat Olanike Busari*

Department of Guidance and Counselling, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Submission: February 02, 2018; Published: September 21, 2018

*Corresponding author: Afusat Olanike Busari, Department of Guidance and Counselling, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, Tel: 234-8088979187; Email: drbukola@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Afusat O B. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depression Among Pregnant Women. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2018; 9(2): 555758. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2018.09.555758.

Abstract

This study examined the prevalence of anxiety and depression and its associated factors, including domestic violence, among pregnant women attending antenatal care at state hospital Moniya, Ibadan Oyo state. The study adopted a cross-sectional research design. Out of all the respondent’s 22 percent of the women were anxious and/or depressed. Psychological distress was associated with husband unemployment (p=0.035), lower household wealth (p=0.029), had above secondary education (p=0.005), a first (p=0.006) and an unwanted pregnancy (p<0.001). The strongest factors associated with depression/anxiety were verbal abuse; 45% of women who were physically and/or sexually abused and 21% of those with verbal abuse had depression/anxiety compared to 43% of those who were not abused. Anxiety and depression commonly occur during pregnancy among women; rates are highest in women experiencing verbal abuse, but they also are increased among women with unemployed spouses and those with lower household wealth. These results suggest that developing a screening and treatment programmed for domestic violence and depression/anxiety during pregnancy may improve the situation of pregnant women.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Depression; Anxiety; Associated factors; Domestic violence; Depression; Anxiety

Introduction

Pregnancy can be defined as the period which starts with the onset of gestation and ends at child birth. It is the stage in which life goes through various physiological and psychological suffering along with expectation and hope. Pregnancy can be a stressful time for expectant mothers.

Pregnancy is a very crucial time when a woman feels insecurity and vulnerability. Psychologically healthy woman often find pregnancy as a means of self-realization. Other women use pregnancy to diminish self-doubts about feminity or to reassure that they can function as women in the most basic sense. Still others view pregnancy negatively that they may fear childbirth or feel inadequate about mothering. At least one in ten mothers in all levels of society, and regardless of socioeconomic conditions experience clinical depression and/ or anxiety before and up to a year after child birth. Pregnancy is a special and joyful period of life. It is a time for great responsibilities and emotional attachment for the pregnant women. It is a period of enormous biological, psychological and social challenges for the mother to be and time of significant life change for women and their partners. It can however be a time of emotional and psychological disturbances when dealing with new demands. Studies have shown that antenatal period is a time of increased liability to mental disorders. The most common psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy and the post-partum period are stress and anxiety disorders.

Leight, et al. [1] submitted that estimates of the prevalence of depression during pregnancy vary depending on the criteria used but can be as high as 16% or more women symptomatic and 5% with major depression. Firm estimates for prenatal anxiety do not exist, nor is there agreement about appropriate screening tools, but past studies suggest that a significant portion of women experience prenatal anxiety both in general and about their pregnancy [2]. Evidence of high exposure to stress in pregnancy is more widely available, at least for certain subgroups of women. For example, a recent study of a diverse urban sample Woods, Melville, et al. [3] found that 78% experienced low-to-moderate antenatal psychosocial stress and 6% experienced high levels. They posited that some of the stressors that commonly affect women in pregnancy around the globe are low material resources, unfavorable employment conditions, heavy family and household responsibilities, strain in intimate relationships, and pregnancy complications.

Herrero, et al. [4] opined that stress is very common among women during pregnancy, and it can cause adverse birth outcomes such as low birth weight. According to Loomans, et al. [5] several studies reported the rates of psychosocial symptoms during pregnancy for the developed world as between 10 and 15%, while in developing countries, the rate was found to be 33% Meijer, et al. [6] observed that there is an association between psychological symptoms and oral health-related problems. Psychological symptoms during pregnancy do exist, are prevalent, and are known to have a range of serious effects on women’s health and their born babies. Peruzzo, et al. [7] in one their study reported that pregnant women adversely affected by psychological symptoms are at high risk for oral diseases.

In another study Silveira, et al. [8] reported that up to 30% of pregnant women are impacted by periodontal disease, while two more studies showed a positive relationship between stress and periodontal disease-related hormonal changes. Oral pain during pregnancy had an adverse effect on low-income pregnant Brazilian women and their quality of life, and the study concludes that without maintaining good oral hygiene, oral complications will lead to difficulty in maintaining emotional balance in eating. Silveira, et al. [8] Since oral health affects overall body health, it is important to emphasize maintaining good oral health among pregnant women and promote oral health within this vulnerable population.

Depressive symptoms tend to be higher when an individual’s relationship adjustment is lower than usual. During pregnancy, relationship adjustment was found to be associated with depressive symptoms. Marital adjustments continue to be significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Researchers such as s Hamid, et al. [9] have found differences in risk factors associated with first onset versus recurrences of depression. Kramer, et al. [10] in their recent study reported that women with both depression and anxiety disorders were at highest risk of low birth weight (LBW) as compared to those with only depressive or anxious symptoms or none.

A recent review found relatively large effects of maternal depressive symptoms on infant birth weight. Woods, et al. [11] asserted that evidence of high exposure to stress in pregnancy is more widely available, at least for certain subgroups of women. For example, a recent study of a diverse urban sample found that 78% experienced low-to-moderate antenatal psychosocial stress and 6% experienced high levels. Dunkel, et al. [12] assumed that depression occurs as frequently during pregnancy as in the postpartum. It has been shown that women prefer psychosocial treatments for depression during the perinatal period. More than a dozen studies on depressed mood or symptoms of trauma found significant effects on gestational age. Changes in relationship adjustment and changes in depressive symptoms vary within individuals at times.

According to Vamos, et al. [13] some of the stressors that commonly affect women in pregnancy around the globe are low material resources, unfavorable employment conditions, heavy family and household responsibilities, strain in intimate relationships, and pregnancy complications. Pregnancy is a significant event in a woman’s life and is associated with psychological and biological changes. Hormonal and lifestyle changes during pregnancy, including physical inactivity and weight gain, as well as low awareness about the importance of prenatal care, may lead to maternal stress and depression, which could persist for many years after childbirth. Herrero, et al. [14] observed that approximately 85% of pregnant women suffer from postpartum mood disorders, which are manifested as depression after pregnancy. Recent studies have shown that depression during pregnancy is more common than postpartum depression Herrero, et al. [14].

Some suggested causes of depression during pregnancy according to Meijer, et al. [6] include family history of depression, having more than three children, low income, age less than 20 years, family violence, gender of previous children, number of female children, cesarean delivery, unwanted pregnancy, lack of social support, stress, parity, and age at marriage. However, the most significant predictive factor for depression after pregnancy is depression before childbirth. Symptoms of depression include emotional instability of mother and infant, mother’s abnormal behaviors, isolation, negligence of recommended care during pregnancy, sleep disorders, and anorexia. Silveira, et al. [8] posited that in children, low birth weight, developmental disorders, growth failure during infancy and childhood, and overweight are among the consequences of depression during pregnancy.

Ko, et al. [15] asserted that impairment of daily activities, lack of prenatal care, poor diet (6), increased rate of abortion due to the consumption of multiple antidepressants (10), smoking and drug abuse, suicidal tendencies, preeclampsia, hypertension, and gestational diabetes are also associated with depression during pregnancy. Depression during pregnancy may ultimately lead to postpartum depression and reduce mothers’ quality of life and breastfeeding. Moreover, the emotional rewards of pregnancy are spoiled due to the need for multiple hospitalizations and medical treatments for the mother and infant.

Stress and anxiety disorders during pregnancy do not only have negative impacts on the course of the pregnancy, it can also affect its outcome, the development of a child and maternal well-being. It is widely recognized that stress during pregnancy may affect neuro -endocrine development in the fetus and the formation of a secure attachment bond with the newborn and, consequently, the socio-emotional development of the child [16]. High anxiety during pregnancy has been linked to lower birth weight, shorter birth length, shorter gestations and increased uterine artery resistance [17]. Anxiety in pregnancy could have long-term effects on children ‘s behavioral/emotional problems [18]. Prominent sources of stress during pregnancy include changing roles, life change, and relationship difficulties. The psychological consequences of such stress may be amplified by hormonal changes that occur during the course of pregnancy. Studies have also found that partner conflict during pregnancy is related to pregnancy related worries or concerns [19] and emotional distress.

Pregnancy is not only a period of great joy, but also one of great stress to a woman both physically and mentally. Even in healthy women, pregnancy may give rise to many anxieties because of anticipated uncertainty associated with it. Evidences from these researchers Catov, et al. [20] Hernandaz, et al. [21], Lobel, et al. [22] & Rauchfuss, et al. [23]. Findings of Lee, et al. [24] & Teixeira [17] have shown that pregnancy anxiety not only affects pregnant women’s health but also have an impact on labor outcomes such as preterm delivery, prolonged labor, caesarean birth, low birth weight. Findings of Lee, et al. [24] & Teixeira [17] revealed a varied prevalence of pregnancy anxiety at different trimesters of pregnancy with high levels in first and third trimesters. A high and diverse prevalence rate of 14-54% pregnant anxiety from different part of the world are reported from previous studies of scholars such as García Rico, Rodríguez, Díez. Real, Hernandez-Martinez, Nieminen & Stephansson and Ryding et al. [17,21,25]. Teixeira. However, most of these studies explored general pregnancy anxiety than pregnancy-specific anxiety.

Consistent effects have been observed in `pregnancy anxiety’ (also known as `pregnancy-specific anxiety’ and similar to `pregnancy distress’). Dunkel Schetter [26] submitted that pregnancy anxiety appears to be a distinct and definable syndrome reflecting fears about the health and wellbeing of one’s baby, of hospital and health-care experiences (including one’s own health and survival in pregnancy), of impending childbirth and its aftermath, and of parenting or the maternal role. It represents a particular emotional state that is closely associated with state anxiety but more contextually based, that is, tied specifically to concerns about a current pregnancy. Dunkel Schetter [27] asserted that assessment of pregnancy anxiety has entailed ratings of four adjectives combined into an index (`feeling anxious, concerned, afraid, or panicky about the pregnancy or use of a 10-item scale reflecting anxiety about the baby’s growth, loss of the baby, and harm during delivery, as well as a few reverse-coded items concerning confidence in having a normal childbirth).

Pregnancy-specific anxiety is defined as worries, concerns and fears about pregnancy, childbirth, and health of infant and future parenting [28]. Serçekuş, et al. [29] reported that nulliparous women’s childbirth fears were related to labour pain, birth-related problems and procedures. Previous researches on pregnancy anxiety concluded that pregnancy-specific anxieties are the real predictors of adverse labour outcomes than general anxiety. These researchers Bayrampour, Heaman, Duncan, and Tough. Huizink, et al. [28] & Reck, et al. [30] recommended that estimation of pregnancy-specific anxiety benefit in identification and risk reduction more specifically. They further explained that with limited evidences available on specific fears and worries related to pregnancy, the structure of pregnancy anxiety and its impact on pregnancy outcomes necessitate further studies exploring pregnancy-specific anxieties and its risk factors.

According to Nierop, et al. [31] multidimensional modeling techniques revealed that state anxiety, pregnancy anxiety, and perceived stress all predicted the length of gestation. But pregnancy anxiety (as early as 18 weeks into pregnancy) was the only significant predictor when all three indicators were tested together with medical and demographic risks controlled. Dunkel [32] posited that women with high pregnancy anxiety were at 1.5times greater risk of preterm birth (PTB) controlling for socio-demographic covariates, medical and obstetric risks, and specific worries over a high-risk condition in pregnancy. Dunkel [32] opined that women who are most anxious about pregnancy seem to be more insecurely attached, of certain cultural backgrounds, more likely to have a history of infertility or to be carrying unplanned pregnancies and have fewer psychosocial resources.

According to Alipour, et al. [33] a prospective study among 160 third trimester Iranian pregnant women, showed a significant relationship between general anxiety and fear of childbirth. Nulliparous women reported higher levels of anxiety in 28thand 38th weeks of gestation than parous. Körükcü, Fırat and Kukulu submitted that study among 660 low risk third trimester Turkish pregnant women revealed a significant relationship between fear of childbirth and general anxiety and higher scores of fears of childbirth in nulliparous women than parous women. An observational cross-sectional study in Northern Ireland among 263 healthy low-risk mothers found that there was a high degree of pregnancy-related anxiety among nulliparous pregnant women [34].

The results obtained by Hall, et al. [35] from a crosssectional descriptive survey conducted among 650 low risk third trimester pregnant women of 17-46 years of age revealed 25% childbirth fear and the authors concluded that the risk factors and timing of heightened anxiety during the transition to motherhood differ in pregnant women. Also, Henderson, et al. [36] reported 14% prevalence of antenatal anxiety from 5332 samples of maternity clinic attendance of England. They identified young maternal age as well as ethnicity as risk factors of pregnancy anxiety. A population-based community study among 916 Swedish first trimester women by Rubertsson, et al. [37] estimated 15.6% prevalence of anxiety symptoms and reported that women under 25 years of age were at an increased risk of anxiety symptoms. They concluded that anxiety symptoms during pregnancy increased the rate of preference for caesarean section. Investigation was conducted by Arch on socio-demographics of pregnant women to find out predictors of pregnancy anxiety in US sample of 311 pregnant women. They concluded that younger age, nulliparous status and high levels of general and state anxiety predicted higher pregnancy-related anxiety. There is a paucity of research on anxiety and depression among pregnant women in Nigeria, this study therefore investigated the prevalence of anxiety and depression among a cross section of women attending antenatal care at the state hospital located in Moniya, Ibadan, Oyo state

DObjectives of the Study

The general objective of this study is to investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression and its associated factors among pregnant women. The specific objectives include:

a) Determine the demographic characteristics of the respondents in relation to anxiety and depression among pregnant women

b) Investigate level of anxiety and depression among pregnant women.

c) Examine the level of domestic violence among pregnant women.

Research questions

The following research questions were formulated and answered in this study

i. What are the demographic characteristics of the respondents in relation to anxiety and depression?

ii. What is the level of anxiety and depression experienced by the respondents?

iii. What is the level of domestic violence experienced by the pregnant women?

Methodology

Design

This study adopted cross sectional research design

Sample and sampling techniques

This cross-sectional study was conducted among pregnant women 20 years and above, visiting State Hospital Moniya in Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo State for Antenatal Care (ANC) during the study period. One hundred and fifty-four (456) women attending routine obstetrical care or antenatal care at the State Hospital, Moniya were approached and encouraged to participate in the study. Participants were recruited prior to undertaking their medical examinations or antenatal classes. Upon giving an informed consent, data on age, educational level, employment, socioeconomic status, marital status, duration of relationship, number of previous children and gestational age were collected. Presences of medical complications in previous and current pregnancies were also recorded. The women were also asked to fill out the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Instrument

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): HADS is a commonly used instrument in hospital setting to determine anxiety and/or depression. It is a ten-point scale used to determine anxiety or depression separately. A total score of ≥8 on the depression or anxiety scale was taken as positive for anxiety or depression. Anxiety or depression status was taken as the outcome variable in the study. Using this instrument, study participants were classified as normal, only anxious, only depressed, or both anxious and depressed. The Urdu translated version of HADS demonstrated satisfactory linguistic equivalence, conceptual equivalence, and scale equivalence (concordance rates at the cutoff of 8 for anxiety and depression subscales were 82.4% and 87.0%, resp., and at the cutoffs of 11 were 91.7% and 98.1%, resp.) with English version

Data collection procedure: The pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria were recruited to the study during their first trimester period. An average antenatal attendance of 60- 75 pregnant women per day assured feasibility for adequate sampling from May 2016- June 2017. A convenient sampling method was used depending upon eligibility and voluntary willingness from those who attended antenatal clinic. Each informed and signed first trimester pregnant woman was contacted by the researcher and interviewed for socio-personal variables in a convenient hall adjacent to antenatal clinic. Then they were asked to self-rate their anxiety and depression level using HADS. Participants were asked to read through each statement in the HADS carefully and then mark their perceived levels of anxiety on a 1-5 rating scale against each statement. Each rating score meaning was explained to them. The average time taken by each participant at initial contact was 25-30 min.

These respondents were followed up in the second and third trimesters during their regular antenatal visits to the clinic and the subsequent data on anxiety levels were collected by the nurses that were trained as research assistant using the same tools. Demographic variables included the participant’s age, level of formal education, employment status, and husband’s employment status. Socioeconomic status was estimated using a measure of overall household wealth. This measure, referred to as the household property index, scored the number of the following items owned by any member of the respondents’ household: home, cultivated land, vehicle, TV, and/or refrigerator. In addition, all participants were asked their number of previous pregnancies and whether the current pregnancy was wanted.

Statistical analysis: First, the researcher estimated the prevalence of depression/anxiety among the respondents by calculating the percentage of respondents who met the criterion for depression/anxiety based on their pre- test scores. The mean and standard deviation was calculated to examine the magnitude of depression and anxiety among the respondents.

Differences in prevalence of depression/anxiety were explored according to the following demographic and background characteristics: age, formal education, employment, husband’s employment, property index, wanting the current pregnancy, number of previous pregnancies and domestic violence reported during the six months prior to the current pregnancy. Chi-square tests were used for comparisons of whether respondents met the criterion for depression/anxiety while t-tests and analyses of variance were used for comparisons of mean scores by demographics

To identify the most salient predictors of psychological distress this may be used to target future interventions. Logistic regression model predicting depression/anxiety based on the demographic and background variables was conducted to determine which variables remained significant after controlling for other possible predictors.

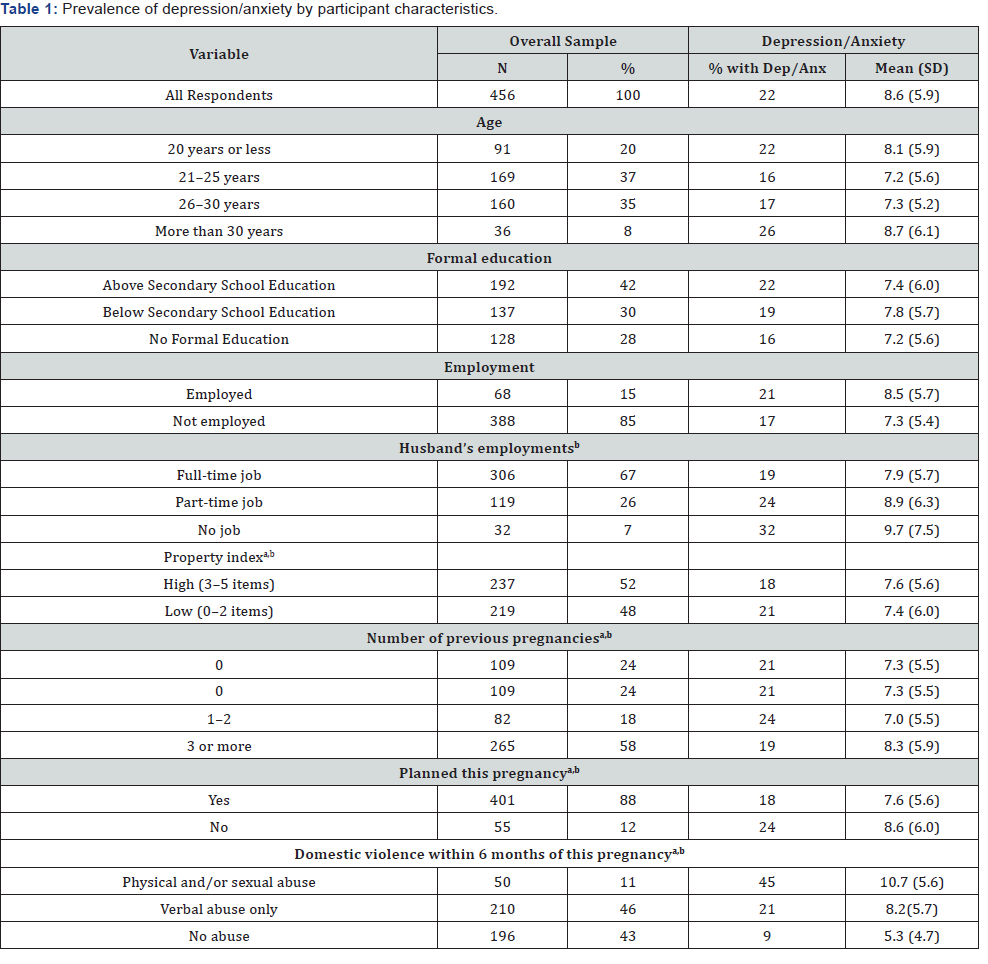

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in (Table 1). Most participants (72%) were between 21 and 30 years of age and 72 percent had some formal education. Fifteen percent were employed, and 67 percent of their husbands had permanent employment. Fifty-two had households that owned 3 or more of the 5 items included in the property index. Twenty -four percent were pregnant for the first time and 88 percent reported that the pregnancy was wanted. About half of the participants (57%) experienced domestic violence in the six months prior to pregnancy with 46 percent reporting verbal abuse only and 11 percent reporting physical and/or sexual abuse.

Note: Depression/anxiety is defined as an HADS score ≥ 11.

a Mean HADS scores varied significantly by characteristic (p< .05) based on analysis of variance

bPercentage of respondents with depression/anxiety varied significantly (p< .05) based on chi-square test

Results

In Table 1, the percent of women with each characteristic that had HADS score of ≥11, the cutoff for a diagnosis of anxiety/ depression. Overall, 22% of this population met the cutoff for depression/anxiety. In this univariate analysis, having a husband who was unemployed, having a low property index, a first pregnancy, an unwanted pregnancy, and a history of verbal and physical and/or sexual abuse all were associated with a HADS score of ≥11. Almost half of the respondent’s 11 percent of women experienced physical and/or sexual abuse and 46 percent were experiencing only verbal abuse had depression/ anxiety compared to 43 percent who reported no abuse. Also, the mean (and standard deviation) of the HADS score associated with each characteristic was evaluated. The overall mean score was 8.6 (5.9). Each of the characteristics associated with a significant increase in the percent of scores ≥ 11 was also associated with a significant increase in the mean score. For example, the mean HADS scores increased with increasing severity of abuse. Women reporting no abuse had a mean score of 4.8, while those reporting verbal abuse only had a mean score of 8.2, and those reporting physical and/or sexual abuse had a mean score of 10.7(p < .001).

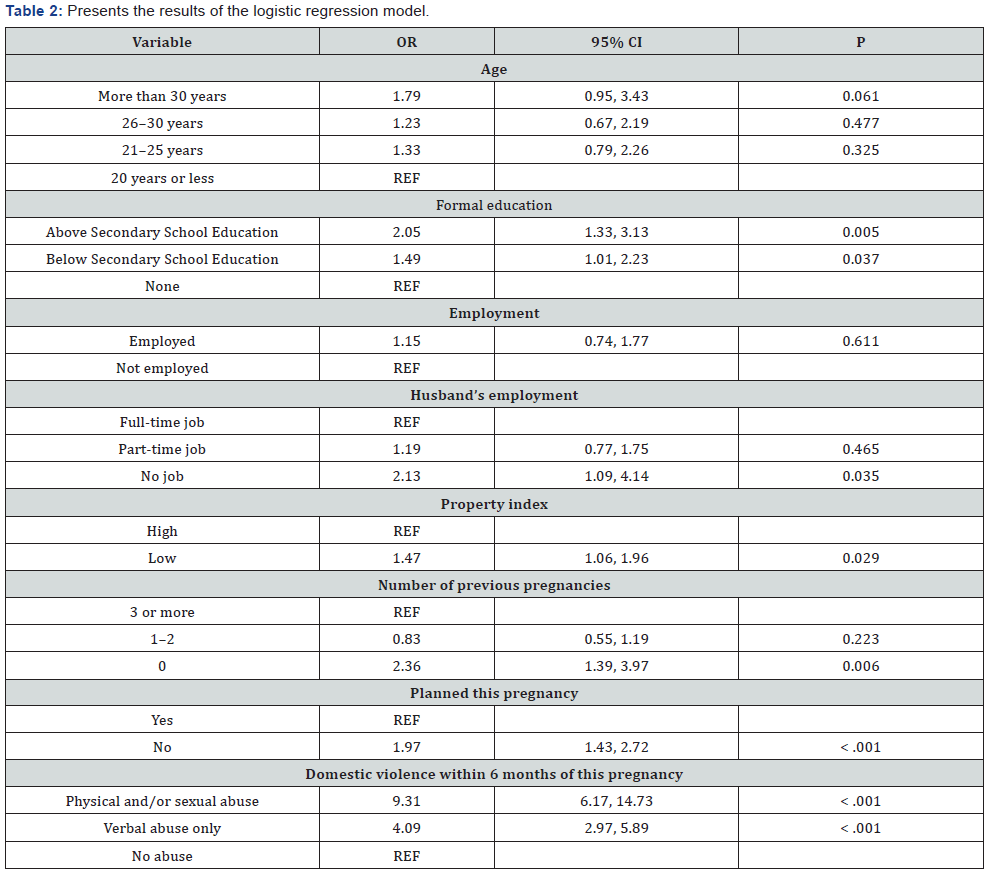

2 presents the results of the logistic regression model. After controlling for the other variables in the model, women with “Above Secondary School education were more often depressed than those without any formal education (OR = 2.05, 1.31-3.12) as were women with “Below Secondary School education (OR = 1.49, 1.01 - 2.23). Women whose husbands had no job were significantly more depressed/anxious (OR = 2.13, 1.09 - 4.15) compared to those whose husbands had a permanent job. In addition, women who had low scores on the property index (two or fewer items owned by their household) were more likely to exhibit depression/anxiety (1.51, 1.06 - 2.09). Women in their first pregnancy were more likely to exhibit depression/anxiety than those who had been pregnant before (OR = 2.35, 1.39 - 3.97). Women who did not plan the current pregnancy also were more likely to be depressed/anxious (OR = 1.99, 1.45 - 2.75). In addition, there was a strong relationship between prior domestic violence and depression/anxiety during pregnancy. Women who were physically and/or sexually abused during the six months prior to their pregnancy were far more likely to have depression/anxiety as compared to those who did not experience any abuse (OR = 9.31, 6.17 - 15.07). Similar, but not quite as striking, results were found for women reporting verbal abuse only (OR = 4.13, 2.89 - 5.93). These findings are consistent with the means and prevalence rates shown in the previous table (Table 1).

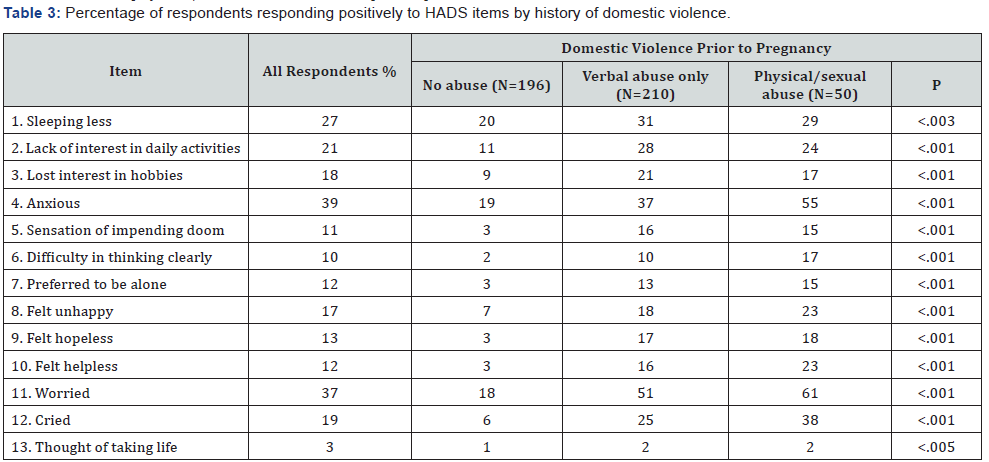

In the current study there existed strong association between history of domestic violence and antenatal psychological distress, this study explored the depression and anxiety symptoms reported by women who experienced different levels of abuse, based on responses to the individual HADS items. In Table 3, the percentage of women reporting that they often or always had a specific symptom by level of abuse was presented. The most commonly reported symptoms overall were anxiety (39%), worry (37%), lack of interest in daily activities (21%) and crying (16%). For each symptom, there was a significant trend of greater symptoms according to increasing level of abuse from no abuse to physical/sexual abuse. For example, 65 percent of women who had been physically and/or sexually abused reported that they were often or always worried compared to 51 percent of those who were verbally abused and 18 percent of those who reported no abuse. In the same vein a little above half the women 55%) were experiencing physical/sexual abuse and 43 percent were experiencing verbal abuse only reported feeling anxious often or always compared to 19 percent who experienced no abuse. Two percent of women who experienced physical/sexual abuse prior to pregnancy thought often or always about taking their own lives compared to one percent of those experiencing no abuse and 2% verbal abuse only.

Discussion

Despite the fact that pregnancy is a time of enormous biological, psychological and social challenges for the pregnant woman the fact that it is a period of fulfillment for the mother to be, it can also be a time of emotional and psychological disturbances when dealing with new demands. In this study, using the HADS scale, it was found that nearly 26 percent of pregnant women met the criteria for depression/anxiety. The result obtained is not surprising comparing the data obtained in the current study to other reports characterizing women’s mental health in some other regions. For instance, a study of the general population of women in the northern area of Pakistan using the AKUADS questionnaire found that 17 percent were anxious or depressed. The prevalence of depressive disorders was 25 percent among women from southern Kahuta, Pakistan in the third trimester of pregnancy. Elsewhere in the region, the prevalence of depression was reported at about 16 percent among South Indian women during the third trimester of pregnancy and among pregnant women in Hong Kong. It is, however, lower than the 34% reported by Pantha and higher than the 14% as reported by Andersson. Similarly, the differences in the prevalence in the various studies could be accounted for by the differences in population studied and the assessment tools used.

Though the rates of depressive symptoms in the current study are comparable to other data obtained from Pakistan and elsewhere in Asia, the prevalence is low compared to the 75 percent overall rates of anxiety and depression reported in community surveys in Pakistan. The different in the various data obtained may be as a result of the fact that the experience of pregnancy may be different for this cohort of women from Hyderabad, Pakistan which has access to skilled pregnancy care. Again, hormonal changes during pregnancy may protect them from mood disorders. More so, local cultural influences may encourage the families to be more supportive and caring towards pregnant women, thus moderating mood disorders.

The study revealed that higher education has an impact on anxiety and depression in pregnant women. In this study, a higher proportion of people who had attained above secondary school educational status had anxiety depression. The negative impact of literacy was pronounced in this study on the prevalence of anxiety and is consistent with the findings by Dunkel-Schetter [38] on education as a risk factor. This could be as a result of the fact that highly educated individuals are more sensitive to the symptoms of anxiety disorders and can easily report them and are not embarrassed about admitting pregnancy related anxiety and depression symptoms. In contrast, other studies from around the world have indicated literacy as protective factor. Literate pregnant women may have good social networks and social support, which has been identified as a protective factor in previous research. Literacy gives individuals a sense of improved self-esteem or self-efficacy, enhances their feelings of self-worth, diminishes feelings of shame, and in turn, anxiety symptoms. Meanwhile, a study by Levin found no association between educational status and pregnancy anxiety.

In this study, age was found to be positively associated with pregnancy related anxiety and depression, this contradicts the findings of Arch who showed that younger age is associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression, whereas others find no relationship between maternal age and pregnancy related anxiety and depression, or mixed findings depending on the timing of assessment. It follows that there is the likelihood that this is a U-shaped effect with women who are of youngest and oldest maternal age having higher stress anxiety. Teen pregnancies are likely to invoke more anxiety as are pregnancies among women more than 35 years old [39].

The results obtained from this study also suggest a strong link between level of abuse and magnitude of depression/anxiety, consistent with studies from other developing and developed countries that have found associations between domestic violence and poor mental health during the childbearing period. In the current study, women who were in an abusive environment during the 6 months before their pregnancy were at greater risk for developing depression/anxiety during pregnancy [40-68].

Conclusion

This study place emphasis on the rising levels of pregnancy specific anxiety and depression, with social and medical factors such as literacy levels, age, marital status and parity playing major roles in the determination of pregnancy related anxiety and depression levels. The study highlights the need for proper education about pregnancy related problems and the need for provision of proper social support for pregnant women in order to reduce the likelihood of pregnancy specific anxiety and depression so as to avert any possible negative outcomes.

References

- Leight KL, Fitelson EM, Weston CA, Wisner KL (2010) Childbirth and mental disorders. Int Rev Psychiatr 22(5): 453-471.

- Dunkel S (2010) Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, bio-psychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Ann Rev Psychol 62: 531-558.

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, et al. (2010) A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(10): 1012-1024.

- Herrero SG, Saldaña MÁ, Rodriguez JG, Ritzel DO (2012) Influence of task demands on occupational stress: gender differences. J Safety Res 43(5-6): 365-374.

- Loomans EM, van Dijk, AE (2013) Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: Results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. European Journal of Public Health 23(3): 485-491.

- Meijer JL, Beijers C, van Pampus MG (2014) Predictive accuracy of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale assessment during pregnancy for the risk of developing postpartum depressive symptoms: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 121(13): 1604-1610.

- Peruzzo DC, Benatti BB, Ambrosano GM (2007) A systematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol 78(8): 1491-1504.

- Silveira ML, Whitcomb BW, Pekow P, Carbone ET, Chasan-Taber L (2016) Anxiety, depression, and oral health among US pregnant women: 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Public Health Dent 76(1): 56-64.

- Hamid F, Asif A, Haider (2008) Study of anxiety and depression during pregnancy. Pak J Med Sci 24: 861-64.

- Kramer MS, Seguin L, Goulet L, Kahn SR, McNamara H, et al. (2009) Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth: the role of stressors, psychological distress and stress hormones. Am J Epidem 169(11): 1319-1326.

- Woods SM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Fan MY, Gavin A (2010) Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(1): 61. e1-e7.

- Dunkel S, Glynn (2011) Stress in pregnancy: empirical evidence and theoretical issues to guide interdisciplinary researchers. In: Contrada R, Baum A (eds.). Handbook of stress science: biology, psychology, and health. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company: 321-343.

- Vamos CA, Walsh ML, Thompson E, Daley EM, Detman L, et al. (2015) Oral-systemic health during pregnancy: exploring prenatal and oral health providers’ information, motivation and behavioral skills. Matern Child Health J 19(6): 1263-1275.

- Herrero SG, Saldaña MÁ, Rodriguez JG, Ritzel TG (2013) Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. European Journal Public Health 23(3): 485-491.

- Ko YL, Lin PC, Chen SC (2015) Stress, sleep quality and unplanned Caesarean section in pregnant women. Int J Nurs Pract 21(5): 454-461.

- Jacobsen T (1999) Effects of postpartum disorders on par-enting and on offspring. In Miller Journal of Perinatal Medicine 39(5): 515-521.

- Teixeira C, Figuerido B, Conde A, Pachecho A, Costa R (2009) Anxiety and depression during pregnancy in Turkey Midwifery 25(2): 155-162.

- O’Connor TG, Caprariello P, Blackmore ER, Gregory AM, Glover V, et al. Obstetrics and Gynecology 110(5): 1102-1112.

- Da Costa D, Larouche J, Dritsa M, Brender W (2000) Variations in stress levels over the course of pregnancy: factors associated with elevated hassles, state anxiety and pregnancy-specific stress. Journal Psychosom Res 47(6): 609-621.

- Catov JM, Abatemarco DJ, Markovic N, Roberts JM (2010) Anxiety and optimism characteristics and pregnancy-related stress among low-risk mothers: Child Health Journal 17(6): 1138-1150.

- Hernandez-Martinez C, Val VA, Murphy M, Busquets PC, Sans JC (2011) Relation between positive and negative maternal emotional states and obstetrical outcomes. Women and Health 51(2): 124-135.

- Lobel M, Cannella DL, Graham JE, DeVincent C, Schneider J, et al. (2008) Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychol 27(5): 604-615.

- Rauchfuss M, Maier B (2011) Biopsychosocial predictors of preterm delivery Journal of Perinatal Medicine 39(5): 515-521

- Lee AM, Lam SK, Lau SM, Chong CSY, Chui HW, et al. (2007). Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstetrics & Gynecology 110(5): 1102-1112.

- Nieminen K, Stephansson O, Ryding EL (2009) Women’s fear of childbirth and preference for cesarean section – A cross-sectional study at various stages of pregnancy in Sweden. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 88(7): 807-813.

- Dunkel Schetter C (2009) Stress processes in pregnancy and preterm birth. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18(4): 205-209.

- Dunkel Schetter C, Lobel M (2011) Pregnancy and birth: a multilevel analysis of stress and birth weight. In: Revenson T, Baum A, Singer J (eds.). Handbook of health psychology 2. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: pp. 427-453

- Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, Robles de Medina PG, Visser GH, Buitelaar JK (2004) Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome? Early Human Development 79 (2): 81-91.

- Serçekuş P, Okumuş H (2009) Fears associated with childbirth among nulliparous women in Turkey. Midwifery 25(2): 155-162

- Reck C, Zimmer K, Dubber S, Zipser B, Schlehe B, et al. (2013) The influence of general anxiety and childbirth-specific anxiety on birth outcome. Archives of Womens Mental Health 16(5): 363-369.

- Nierop WB, Zimmermann E (2008) Stress-buffering effects of psychosocial resources on physiological and psychological stress response in pregnant women. Biol Psychol 78(3): 261-268.

- Dunkel S (2010) Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, bio-psychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Ann Rev Psychol 62: 531-558

- Alipour Z, Lamyian ME, Hajizadeh ME (2012) Anxiety and fear of childbirth as predictors of postnatal depression in nulliparous women. Women Birth 25(3): e37-e43.

- Lynn FA, Alderdice FA, Crealey GC, McElnay JC (2011) Associations between maternal characteristics and pregnancy-related stress among low-risk mothers: An observational cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 48(5): 620-627.

- Hall WA, Stoll K, Hutton EK, Brown H (2012) A prospective study of effects of psychological factors and sleep on obstetric interventions, mode of birth, and neonatal outcomes among low-risk British Columbian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12: 78.

- Henderson J, Maggie R (2013) Anxiety in the perinatal Perio: Antenatal and postnatal influences and women’s experience of care Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 31(5): 465-478.

- Rubertsson C, Hellstrom J, Cross M, Sydsjo G (2014) Anxiety in early pregnancy: Prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Womens Ment Health 17(3): 221-228.

- Dunkel S (2009) Stress processes in pregnancy and preterm birth. Curr Directions Psychol Sci 18: 205-209.

- Barbato Avanzo (2008) Efficacy of couple therapy as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatr Quart 79(2): 121-132.

- Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A (2004) Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 103(4): 698-709.

- Bergink V, Kooistra L, Lambregste-van den Berg MP, Wijnen H, Bunevicius R, et al. (2011) Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy. J Psychosom Res 70(4): 385-389.

- Beydoun H, Saftlas AF (2008) Physical and mental health outcomes of prenatal maternal stress in human and animal studies: a review of recent evidence. Pediatric Perinat Epidemiol 22(5): 595-596.

- Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, Emond A (2008) The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG 115(8): 1043-1051.

- Donnell C, O’Connor TG, Glover V (2009) Prenatal stress and neurodevelopment of the child: focus on the HPA axis and role of the placenta. Develop Neurosci 31(4): 285-292.

- Faisal Cury A, Menezes PR (2007) Prevalence of anxiety and depression during pregnancy in a private setting sample. Arch Womens Ment Health 10(1): 25-32.

- Fall A, Goulet L, Vézina M (2013) Comparative study of major depressive symptoms among pregnant women by employment status. Springerplus 2(1): 1-11.

- Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Figueiredo B, Deeds O, et al. (2010) Comorbid depression and anxiety effects on pregnancy and neonatal outcome. Infant Behav Develop 33(1): 23-29.

- Flynn HA, O’Mahen HA, Massey L, Marcus S (2006) The impact of obstetrics clinic-based intervention on treatment use for perinatal depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 15(10): 1195-1204.

- Gausia K, Fisher C, Ali M, Oosthuizen J (2009) Antenatal depression and suicidal ideation among rural Bangladeshi women: a communitybased study. Arch Womens Ment Health 12(5): 351-358.

- Goodman JH (2009) Women’s attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to perinatal depression. Birth 36(1): 60-69.

- Guxens M, Tiemeier H, Jansen PW, Raat H, Hofman A, et al. (2013) Parental psychological distress during pregnancy and early growth in preschool children: the generation R study. Am J Epidemiol 177(6): 538-547.

- Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H (2005) Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 105(6): 1442-1450.

- Hübner L B, Hausner H, Wittmann M (2012) Recognizing and Treating Peripartum Depression. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109(24): 419-424.

- Jabbari Z, Hashemi H, Haghayegh SA (2012). Survey on effectiveness of cognitive behavioral stress management on the stress anxiety, and depression of pregnant women. Health System Research 8(7): 1341- 1347.

- Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, et al. (2010) Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(1): 5-14.

- Love C, David RJ, Rankin KM, Collins JW (2010) Exploring weathering: effects of lifelong economic environment and maternal age on low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth in African- American and white women. Am J Epidemiol 172(2): 127-134

- Mahen F (2008) Preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for depression during the perinatal period. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 17(8): 1301-1309.

- Orr R, Blazer J (2007) Maternal prenatal pregnancy related anxiety and spontaneous preterm birth in Baltimore. Psychosom Med 69(6): 566-570.

- Peen J, Schoevers R, Beekman A, Dekker J (2010) The current status of urban‐rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 121(2): 84-93.

- Ross McLean (2006) Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period, a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 67(8): 1285- 1298.

- Sajjadi H, Kamal SHM, Rafiey H, Vameghi M, Forouzan AS, et al. (2013) A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of depression among Iranian adolescents. Glob J Health Sci 5(3): 16-27.

- Stewart DE (2011) Depression during pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine. 365(17): 1605-1611.

- Stroud D, Davila J, Moyer A (2008) The relationship between stress and depression in first onsets versus recurrences: A meta-analytic review. J Abn Psychology 117(1): 206-213.

- Waqas A, Raza N, Lodhi HW, Muhammad Z, Jamal M, et al. (2014) Psychosocial determinants of antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan: Issocial support a mediator? Peer Journal of Pre-Prints 3(2): e463.

- Westdahl C, Milan S, Magriples U, Kershaw TS, Rising SS, et al. (2007) Social support and social conflict as predictors of prenatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 110(1): 134-140.

- Whitton S, Markman Baucom (2008) Women’s weekly relationship functioning and depressive symptoms. Peers Relationships 15(4): 533-550.

- Witt W P, De Leire T, Hagen EW, Wichmann MA, Wisk LE, et al. (2010) The prevalence and determinants of antepartum mental health problems among women in the USA: a nationally representative population-based study. Arch Womens Ment Health 13(5): 425-437.

- Guardino CM, Dunkel Schetter C (2014) Under-standing Pregnancy Anxiety. Zero to Three 34(4): 12-21.