Multiple Cerebral Cavernoma Associated with Biatrial Myxoma: A Case Report

Babak Alijani1, Amir reza Ghayeghran2 and Seifolla Jafari3*

1 Associate Professor of Neurosurgery, Guilan University of medical sciences, Iran

2Associate Professor of Neurology, Guilan University of medical sciences, Iran

3Resident of Neurosurgery, Guilan University of medical sciences, Iran

Submission: November 14, 2018; Published: August 24, 2018

*Corresponding author: Seifolla Jafari, Resident of Neurosurgery, Guilan University of medical sciences, Iran; Email: jafariseifolla@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Seifolla J, Babak A, Amir reza G. Multiple Cerebral Cavernoma Associated with Biatrial Myxoma: A Case Report. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2018; 8(3): 555743. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2018.08.555743.

Abstract

A 38-year old man with a past medical history of bipolar disorder known for 8 years and treated medically. He experienced multiple episodes of right hemi facial paresis for the last 2 years which worsened in the previous year followed by ataxia, dizziness, diplopia, vomiting and loss of consciousness. an axial Transthorasic echocardiography showed large mobile biatrial masses which was resected surgically and both tumors had the histopathological feature of benign cardiac myxoma and brain CT scan without contrast showed multiple sub cortical hyperdense lesions. One year later brain MRI with gadolinium showed two large hyperintense lesions and patients underwent surgery for resection of both intracranial lesions. The masses have typical morphological features of a cavernoma and both of them reported cavernomas histopathologically without metastatic evidence. Cavernoma is a vascular hamartoma, characterized by channels which are separated from brain tissue by a thin adventitia layer. Several cavernomas have been reported in association with other mesenchymal anomalies in other organs including the retina angiomas, liver Angiosarcoma, skin angioma, liver and skin cavernoma but only three cardiac myxoma associated with cavernomas have been reported.

Keywords: Cavernoma; Myxoma; Biatrial; Liver; Skin cavernoma; Dizziness; Diplopia; Vomiting; Tumors; Vascular hamartoma; Cardiac tumors; Symptoms of myxomas; Echocardiography; Kidney; Organs; Syndrome; Breath; Cerebral hemorrhage

Introduction

Cavernoma is a vascular hamartoma, characterized by channels which are separated from brain tissue by a thin adventitia layer [1,2]. These channels are actually dilated blood vessels and consist of an abnormal endothelial layer. It can cause seizures or neurological deficits as a result of blood leakage and the deposition of hemeosiderin in the surrounding brain parenchyma [3-5].

The prevalence of cavernomas is 0.5% and include 5-13% of all vascular brain lesions. Cavernomas may occur in a sporadic or familial manner and multiple lesions occur mostly in the familial type. Also, symptoms such as seizures and bleeding occur more in the familial type of cavernomas. Symptoms of both sporadic and familial cavernomas usually occur between 2 to 4 decades [6,7]. A cavernoma is an autosomal dominant disease with incomplete penetration and with variable expression of genes (CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3). It has been found that 94% of the familial type and 57-71% of patients with multiple lesions, having no family history of the disease, have one of these gene mutations. In single lesion types, there is mutation in one of these three genes in 50% of cases [8-10].

The association of cavernomas with other anomalies such as intra-cranial aneurysms and vascular abnormalities of other organs such as the liver, kidney, skin and retina has already been explained [11-14].

Although it is a rare tumor and occurs in less than half percent of the general population, myxoma is the most common type of primary cardiac tumors in all ages and accounts for 3/4 of treated cardiac tumors. Its origin is the mesenchymal pleury potent cells in the sub endocardial layer and it is able to transform into multiple forms of cells such as epithelial, vascular and muscular cells [5,15-17]. Most myxoma lesions are sporadic but at least 7% occur in a familial autosomal dominant syndrome. These syndromes have previously been referred to as NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoidneurofibroma, and ephelides) or LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxoma, andblue nevi). Now it is referred to as carny complex and it consists of familial cardiacmyxomas associated with endocrine overactivity such as Cushing syndrome and spotty pigmentation of the skin (lentiginosis) with a variety of other benign neoplasms including schwannomas and pituitary or thyroid adenomas and extracardiac myxomas but CCM was not described as part of the Carney complex [18-22].

The most common symptoms of myxomas including shortness of breath, platy pnea, nocturnal dyspnea, dizziness, cough, chest pain, faint, Reynaud’s syndrome and pre-systolic heart murmur. The neurological symptoms include hemiparesis, visual impairment may also be presented. The most important causes include emboli, mycotic aneurysms, intra cerebral hemorrhage and in rare cases metastasis [23-27].

Case report

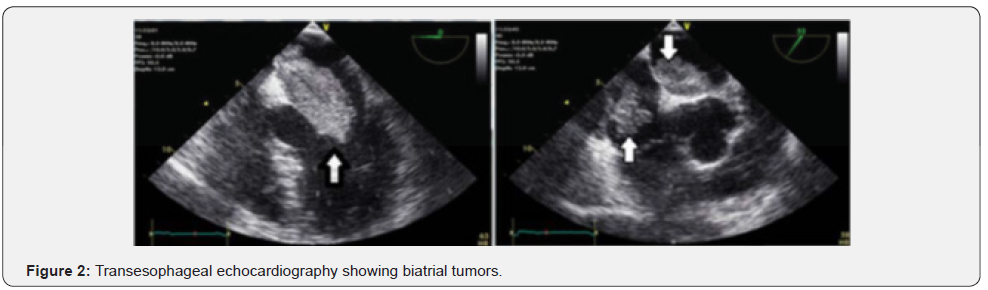

The patient is a 38-year old man with a past medical history of bipolar disorder known for 8 years and treated medically. He experienced multiple episodes of right hemi facial paresis for the last 2 years which worsened in the previous year followed by ataxia, dizziness diplopia and vomiting. Only dilated pupils and ataxia were found in the neurological examinations. Sensory examination, muscle strength and examinations of cranial nerves were normal. Multiple sub-cortical hyper dense lesions in the brain CT scan were detected with compression, mostly at the right parietal lobe. The same lesions were seen on the MRI hyper signal on T1 with GAD (Figure 1). In other surveys, RBBB and right axis deviation in ECG were observed with sinus rhythm. Auscultation of the heart and lungs were normal. Echocardiography was performed, and bilateral atrial mass was seen on transthoracic echocardiography. Echocardiography (TEE) revealed the left atrial mass size of 60 in 27mm and right sided mass 43 in 31 mm in the right atrium (Figure 2). The patient underwent surgery to remove the tumor via median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass was performed.

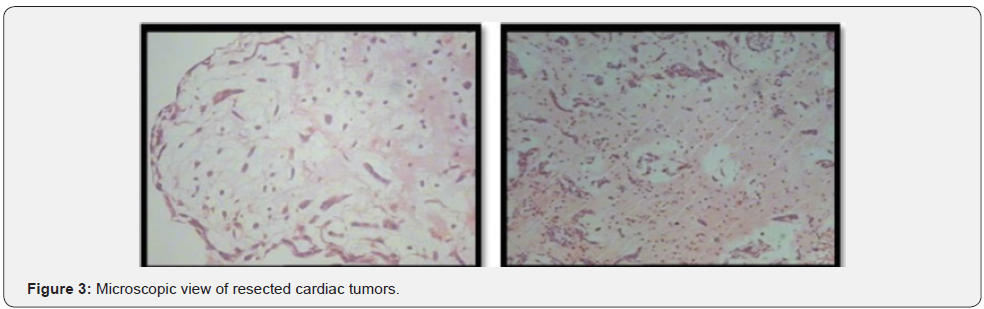

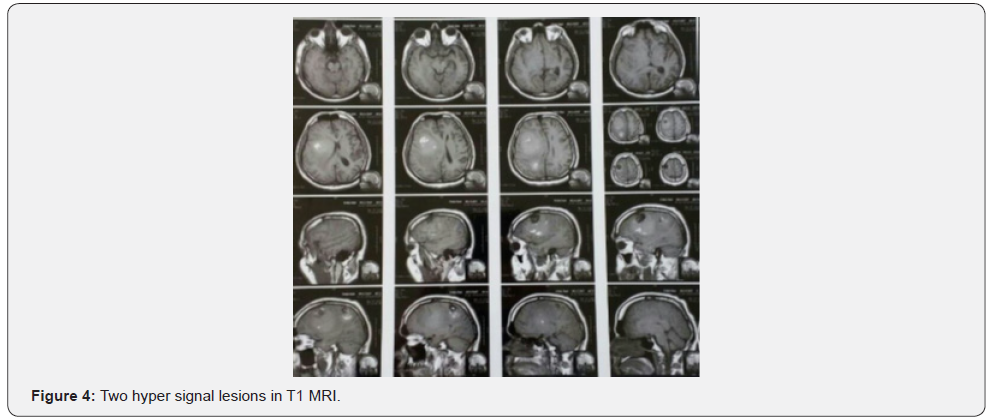

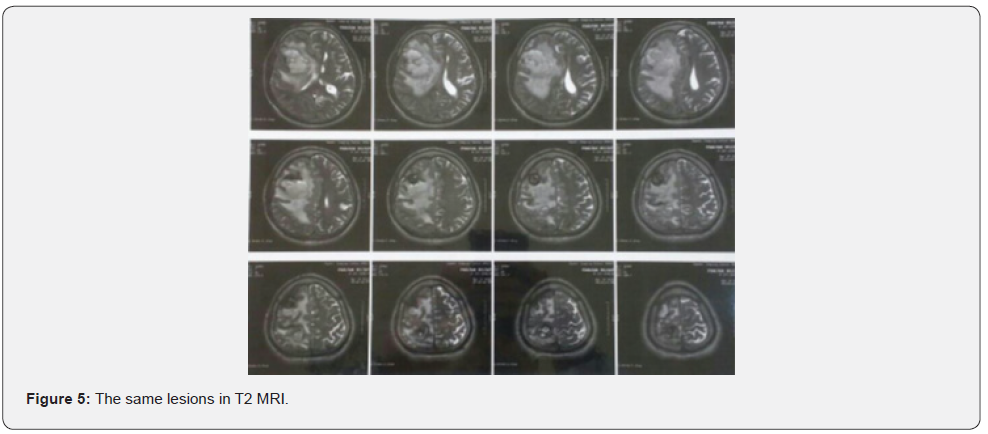

Both masses reported benign cardiac myxoma (Figure 3). No more work up was done for intra cranial lesions. New neurological deficits occurred 3 weeks before admission. Right hemi facial paresis, left hemi paresis (4/5), ataxia and several generalized tonic-clonic seizures developed. Other neurologic examinations were normal. In the Brain, CT scan space occupying lesions with low attenuation and severe edema was seen in the right parieto-occipital lobe which enlarged when compared to the images of the previous year. Two hyper signal lesions at the right parieto-occipital lobe with severe edema were seen in T1 and T2 and popcorn or burry view at GAD T1 MRI seen (Figures 4-6). In other surveys, including abdominal and pelvic ultrasonography, abdominal CT scan and fondus examination, there was no pathologic finding.

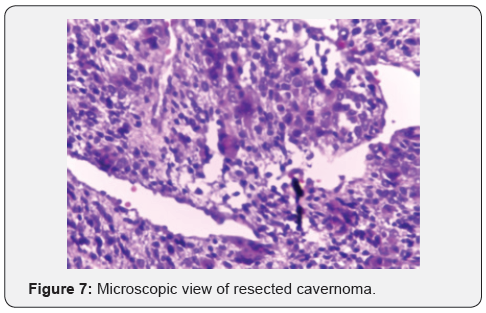

Patients underwent surgery for resection of both intracranial lesions at the same time with complete resection of hemeosiderin deposit. The masses have typical morphological features of a cavernoma. After one month, all the neurologic deficits were revealed, and seizure was controlled by just one antiepileptic drug. The lesions reported histopathological cavernomas without metastatic evidence (Figures 7&8).

Discussion

Cardiac myxoma is a benign rare tumor. Based on records, 80% of cases occur in the left atrium and right atrium counts for 18% of cases and only 2.5% of cases are presented bilaterally [28,29]. The peak age for the occurrence of myxoma is between 40 to 60 with female to male ratio of 3:1 Patients with myxoma are usually normal on physical examination and therefore, may be asymptomatic and undetected for a long period. Carney syndrome is usually presented by abnormal physical examination including cardiac myxoma, increased endocrinal activity and skin hyper pigmentation [30,31]. The patient described has no evidence of carney syndrome or family history of it.

Several studies have explained the role of genetics in CCM. The familial type of CCM that accounts for 10-20% of it, is an autosomal dominant disease. In patients with multiple CCM and without a family history, 71-75% have a de novo mutation [9,10]. Also, 75% of asymptomatic patients inherited it from their parents. This shows the importance of genetic roles, especially in multiple lesions. Several CCM have been reported in association with other CNS tumors including schwannomas and spinal CM [32-35]. CCM is also associated with mesenchymal anomalies in other organs including the retina angiomas, liver Angiosarcoma, skin angioma, liver and skin CM have been reported. None of the anomalies noted in our patient was found [11,13,36-38].

Thus far, three cardiac myxoma associated with CCM have been reported. In 2008, Ardeshir and colleagues reported hepatic CM also but in other cases such as our patient, only a myxoma and CCM was reported in association. Based on the role of genetics in CCM and bilateral myxoma, it leads to a mutation role to justify their company rather than simultaneous occurrence of both incidentally. According to limited genetic analysis facilities in our center and unwillingness of patient’s family to workups, the confirmation of genetic or familial association of CCM and myxoma observed in this patient was not possible and more patients are needed to confirm or disprove this theory.

References

- Atherton DJ, Pitcher DW, Wells RS, MacDonald DM (1980) A syndrome of various cutaneous pigmented lesions, myxoid neurofibromata and atrial myxoma: the NAME syndrome. Br J Dermatol 103(4): 421-429.

- Mao Y, Zhao Y, Zhou LF, Huang CX, Shou XF, et al. (2005) A novel gene mutation (1292 deletion) in a Chinese family with cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery 56(5): 1149-1153.

- Laurans MS, DiLuna ML, Shin D, Niazi F, Voorhees JR, et al. (2003) Mutational analysis of 206 families with cavernous malformations. J Neurosurg 99: 38-43.

- Clatterbuck RE, Eberhart CG, Crain BJ, Rigamonti D (2001) Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical evidence that an incompetent blood-brain barrier is related to the pathophysiology of cavernous malformations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71(2): 188- 192.

- Burke AP, Virmani R (1993) Cardiac myxoma. A clinicopathologic study. Am J Clin Pathol 100(6): 671-680.

- Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Kestle JR (1995) The natural history of cerebral cavernous malformations. J Neurosurg 83(5): 820-824.

- Rigamonti D, Johnson PC, Spetzler RF, Hadley MN, Drayer BP (1991) Cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasia: a spectrum within a single pathological entity. Neurosurgery 28(1): 60-64.

- Denier C, Goutagny S, Labauge P, Krivosic V, Arnoult M, et al. (2004) Mutations within the MGC4607 gene cause cerebral cavernousmalformations. Am J Hum Genet 74: 326-337.

- Felbor U, Gaetzner S, Verlaan DJ, Vijzelaar R, Rouleau GA, et al. (2007) Large germline deletions and duplication in isolated cerebral cavernous malformation patients. Neurogenetics 8(2): 149-153

- Drigo P, Battistella PA, Mammi I, Ricchieri G, Carollo C (1994) Familial cerebral, hepatic, and retinal cavernous angiomas: a new syndrome. Child’s Nervous System 10(4): 205-209.

- Giombini S, Morello G (1978) cavernous angiomas of the brain: account of fourteen personal cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Weien) 40(1-2): 61-82.

- Janssens J, Boland B, Draguet AP, Van Beers BE, Godfraind C, et al. (1999) Diffuse liver angiosarcoma and cerebral cavernous angiomas in a young patient. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 62(4): 446-449

- Pascual-Castroviejo I (1985) The association of extracranial and intracranial vascular malformations in children. Can J Neurol Sci 12(2): 139-148.

- Reynen K (1995) Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 333(24): 1610-1617.

- Ferrans VJ, Roberts WC (1973) Structural features of cardiac myxomas. Histology, histochemistry, and electron microscopy. Hum Pathol 4(1): 111-146.

- Steinmetz EF, Calanchini PR, Aguilar MJ (1973) Left atrial myxoma as a neurological problem: a case report and review. Stroke 4(3): 451-458.

- Farah MG (1975) Familial atrial myxoma. Ann Intern Med 83(3): 358- 360.

- Kigawa I, Fukuda S, Marat D, Tanaka J, Ikeda S, et al. (1996) A case of familial cardiac myxoma (in Japanese). Kyobu Geka 49: 323-326

- Singh SD, Lansing AM (1996) Familial cardiac myxoma-a comprehensive review of reported cases. J Ky Med Assoc 94(3): 96-104.

- Vaughan CJ, Veugelers M, Basson CT (2001) Tumors and the heart: molecular genetic advances. Curr Opin Cardiol 16(3): 195-200.

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, Perez-Atayde AR (1984) Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 10(1): 72-82.

- Knepper LE, Biller J, Adams HP Jr, Bruno A (1988) Neurologic manifestations of atrial myxoma. A 12-year experience and review. Stroke 19(11):1435-1440.

- Samaratunga H, Searle J, Cominos D, Le Fevre I (1994) Cerebral metastasis of an atrial myxoma mimicking an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol 18(1): 107-111.

- Wada A, Kanda T, Hayashi R, Imai S, Suzuki T, et al. (1993) Cardiac myxoma metastasized to the brain: potential role of endogenous interleukin-6. Cardiology 83(3): 208-211.

- Roeltgen DP, Weimer GR, Patterson LF (1981) Delayed neurologic complications of left atrial myxoma. Neurology 31(1): 8-13.

- Sabolek M, Bachus-Banaschak K, Bachus R, Arnold G, Storch A (2005) Multiple cerebral aneurysms as delayed complication of left cardiac myxoma: a case report and review. Acta Neurol Scand 111(6): 345-350.

- Zhenghua X, Wei M, Da Z, Eryong Z (2012) A Typical Bilateral Atrial Myxoma: A Case Report. Case Reports in Cardiology :460268

- Crafoord C (1955) Discussion on mitral stenosis and mitral insufficiency. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Cardiovascular Surgery, Philadelphia, Saunders. American Journal of Medical Case Reports. 4(1): 202-211.

- Basson CT, Aretz HT (2002) Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 11– 2002. A 27-year-old woman with two intracardiac masses and a history of endocrinopathy. N Engl J Med 346(15): 1152-1158.

- Carney JA, Gordon H, Carpenter PC, Shenoy BV, Go VL (1985) The complex of myxomas, spotty pigmentation, and endocrine overactivity. Medicine (Baltimore) 64(4): 270-283

- Labauge P, Laberge S, Brunereau L, Levy C, Tournier-Lasserve E (1998) Hereditary cerebral cavernous angiomas: clinical and genetic features in 57 French families. Societe Francaise de Neurochirurgie. Lancet 352(9144): 1892-1897.

- Kimura T, Sako K, Ishizaki T, Hashizume K, Yonemasu Y, et al. (1996) Familial multiple cavernous angioma in the brain and spinal cord. No To Shinkei 48(10): 955-959.

- Vishteh AG, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF (1999) Patients with spinal cord cavernous malformations are at an increased risk for multiple neuraxis cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery 45(1): 30-32.

- Feiz-Erfan I, Zabramski JM, Herrmann LL, Coons SW (2006) Cavernous malformation within a schwannoma: review of theliterature and hypothesis of a common genetic etiology. Acta Neurochir(Wien) 148(6): 647-65216.

- Felbor U, Sure U, Grimm T, Bertalanffy H (2006) Genetics of cerebral cavernous angioma. Zentralbl Neurochir 67(3): 110-116.

- Dobyns WB, Michels VV, Groover RV (1987) Familial cavernous malformations of the CNS and retina. Ann Neurol 21(6): 578-583.

- Fukushima T, Ohkawa M, Tomonaga M (1986) Multiple and familial cavernous angiomas in the brain and extremities–case report. No Shinkei Geka 14(3 suppl): 423-428.

- Aghajankhah MR (2016) Biatrial cardiac myxoma: a case report. American journal of medical case report 4(1): 22-25.