Hospitalized Patients Care Pathway for Stroke and its Determinants in a Reference Hospital in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso)

Lompo Djingri Labodi1*, Dao Ben Aziz2, Diallo Ousséini2, Ouedraogo Adja Mariam3, Konate Lassina1, Napon Christian2 and Kabor EB Jean2

1University Hospital of Tingandogo, Unit of Formation and Research of the Sciences of the Health, University Ouaga I Pr Joseph Ki-Zerbo, Burkina Faso

2 University Hospital of Yalgado Ouedraogo of Ouagadougou, Unit of Formation and Research of the Sciences of the Health, University Ouaga I-Pr Joseph KiZerbo, Burkina Faso

3 Department of Medical Biology and Public Health, Institute of Research in Health Sciences, Burkina Faso

Submission: January 18, 2018; Published: July 18, 2018

*Corresponding author: Lompo Djingri Labodi, University Hospital of Tingandogo, Unit of Formation and Research of the Sciences of the Health, University Ouaga I PrJoseph Ki Zerbo, Burkina Faso, Tel: +22670-23-98-34; Email: labodilompo@yahoo.fr

How to cite this article: Lompo D L, Dao B A, Diallo O, Ouedraogo A M, Konate L, et al. Hospitalized Patients Care Pathway for Stroke and its Determinants in a Reference Hospital in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2018; 8(1): 555727. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2018.08.555727.

Abstract

Background: Stroke units and intravenous thrombolysis have been shown to be effective in reducing mortality and post stroke functional sequelae, but they are still embryonic in sub Saharan Africa. However, even in developed countries, long hospital and intra hospital delays still limit their access, hence the interest of a study on the care pathway of patients hospitalized for stroke and its determinants at the Tingandogo University Hospital, in Ouagadougou

Patients and methods: This was a prospective longitudinal study of patients consecutively admitted to the Tingandogo University Hospital, from May 2015 to April 2016, for stroke. Sociodemographic data, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, clinical and neuroradiological data were analyzed, as well as the characteristics of the pre- and intra hospital care pathway. Anunivariate and multivariate analysis was performed.

Result:52 patients (49.5%) consulted at a health center within ≤3h; 17patients (16.2%) consulted directly with the CHU medical emergencies; 39 patients (37.1%) received cerebral CT scan within ≤2h; pre hospital transport by ambulance and the initial clinical severity of stroke (NIHSS≥17) were independent factors associated with early first time delay; urban residence was the only independent variable associated with early admission to emergency departments; vascular risk factors, pre hospital transport by an ambulance and the initial use of a physician were independent factors associated with early CT scan.

Conclusion: The implementation of an organized network of pre and intra hospital care centered on the stroke units, public awareness and training of health professionals on stroke, will reduce the delays in hospital management of stroke.

Keywords: Stroke; Admission times; Cerebral CT scan; Determinants

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of adult death, dementia and disability in the world. Sub Saharan Africa lags behind in the establishment of stroke units (SU) and intravenous thrombolysis (IV) of acute cerebral infarctions, while their impact on reducing mortality and functional disability is today universally proven [1,2]. SU have recently been introduced in some countries such as Congo-Brazzaville [3] or Côte d’Ivoire [4], with the impact of reducing early mortality [3,4] and a reduction of intra hospital medical complications [4]. To our knowledge, in no country in sub Saharan Africa, IV thrombolysis of cerebral infarctions by tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) has yet to be performed in routine practice. However, even in the developed countries, the long prehospital and intra-hospital delays still limit their access particularly to thrombolysis [4-8]. It therefore seemed interesting to us to carry out a study on the care pathway of hospitalized patients for stroke and its determinants, at Tingandogo Teaching Hospital in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso).

Methodology

It was a cross-sectional, prospective, descriptive and analytical study of patients who were residents of the city of Ouagadougou or neighbouring localities within a radius of approximately 50km, consecutively hospitalized for stroke at the Tingandogo Teaching Hospital in Ouagadougou, in Burkina Faso, from May 2015 to April 2016. All adult patients over the age of 16, admitted for recent stroke up to 7days old, clinically diagnosed and confirmed by cerebral CT, with their informed consent, have been included, except those whose age was <16 years, those whose stroke had not been confirmed by neuroimaging or was more than 7 days old or whose consent had not been obtained.

For each patient, the following data were obtained from the patient or his entourage and/or indicated in the clinical file: age, sex, level of education, residence, distance from the place of residence to Tingandogo University Hospital (according to the patient’s or his entourage’s estimates and comparison with map data of Ouagadougou commune and surrounding localities), transport vector (ambulance or personal transportation), vascular risk factors, history of stroke, comorbidities, NIHSS score at admission, clinical severity of stroke at admission (NIHSS≥17, and/or disorders of consciousness), nature of stroke, first referral health structure (health and social promotion center, or nursing practice, medical center or medical practice, private clinic, Tingandogo University Hospital), profile of the first referral health professional (paramedical or medical doctor), admission to the 1st health facility since the beginning of the stroke (hours), admission to the emergency department of Tingandogo University Hospital after the start of stroke (hours), time to perform the brain scan since the patient arrived in the emergency room (hours). The time of onset of stroke was equated with the time of the first sign or symptom. When it came to a waking stroke, the start time was when the patient was last seen to be free of any neurological deficit.

The different delays in the care pathway were respectively categorized into 2 categories, namely: first-time care, early (≤3hours) or late (>3hours); emergency admission time to CHU, early (≤3hours) or late (>3hours); time to perform cerebral CT, early (≤2hours) or late (>2hours). These different delays were evaluated according to the compatibility with IV thrombolysis time of 4h30 and the recommendations of the European Stroke Organization (ESO 2008).

Statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS12 software. Student’s t-test was used to compare the means and Pearson’s Chi-square test to compare percentages; the value of p<0.05 was considered a threshold of statistical significance. Univariate and multivariate analyzes with logistic regression were performed to identify independent factors influencing the care pathway of our patients. Only variables with a p value of <0.20 in univariate analysis were considered for multivariate analysis. Ethical clearance was granted by the ethics committee of the the training and research unit of the health sciences of Ouaga University I Professor Joesph KI-Zerbo. A study permit has been obtained from the administration of Tingandogo University Hospital. Medical secrecy has been respected.

Result

Socio demographic and clinical characteristics

The mean age was 61.1 years (range 21-88 years); 22 patients (21%) were aged ≤50 years; 48 patients (45.7%) had no level of education compared to 57 patients (54.3%) who had at least a primary level of education; 44 patients (41.9%) came from surrounding localities of Ouagadougou while 61 patients (68.1%) resided in the commune of Ouagadougou; 61 patients (58.1%) lived within ≤10km of the hospital, compared to 44 patients (41.9%) who resided more than 10km from the hospital; 31 patients (29.5%) were referred to hospital emergency departments via an ambulance, versus 74 patients (70.5%) who came by personal means of transport. At least one vascular risk factor (VRF) was found in 74 patients (70.5%); 31 patients (29.5%) had a history of stroke; comorbidities were found in 43 patients (41%).There were 82 cases of ischemic stroke (78.1%) and 23 cases of hemorrhagic stroke (21.9%); 44 patients (41.9%) had signs of severity at admission; the mean NIHSS was 15.8 (range 4-42) and 44 patients (41.9%) had severe neurological impairment (NIHSS ≥17) on admission.

Care pathway

The median time to admission to the first referral health facility after the onset of stroke was 5 hours (±23); 52 patients (49.5%) arrived at the first referral health facility early (≤3hours) after the stroke and 53 patients (50.5%) arrived within late (>3hours); only 17 patients (16.2%) went directly to Tingandogo University Hospital’s medical emergencies after their stroke. The first health care provider after the stroke occurred was a medical doctor in 70 patients (66.7%) versus a paramedic (state certified nurse most often) in 35 patients (33.3%). The median admission time to Tingandogo CHU was 24 hours (±68); 23 patients (21.9%) arrived early (≤3hours) compared with 82 patients (78.1%) who arrived late (>3hours). The median time to perform CT scan from admission to the emergency room was 6 hours (±20); 39 patients (37.1%) received cerebral CT within an early time (≤2hours) and 66 patients (62.9%) within a delayed time (>2hours).

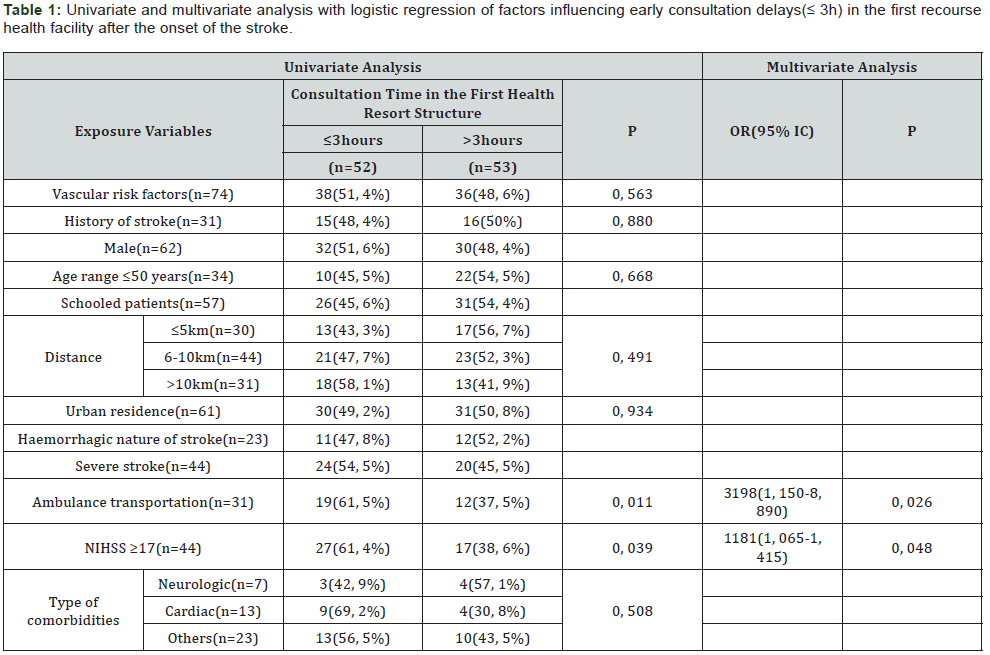

Variables influencing admission times in the 1st health facility: Table 1 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of the variables influencing admission delays in the 1st health structure after the onset of stroke. In univariate analysis, pre-hospital transportation by ambulance (p=0.011) and initial severity of neurological deficit (admission NIHSS ≥17) (p=0.039), were the variables significantly associated with a primary care waiting period early (≤3 hours) after the onset of stroke.

In multivariate analysis with logistic regression, pre-hospital transportation by ambulance (versus pre-hospital transport by personal vehicle) (OR=3.198, 95% CI: 1.150-8.890, p=0.026) and the initial clinical severity of stroke (NIHSS≥17) (OR 1.181, 95% CI: 1.065-1.415), were independently associated with an early admission delay (≤3hours) in the 1st health facility after the onset of stroke.

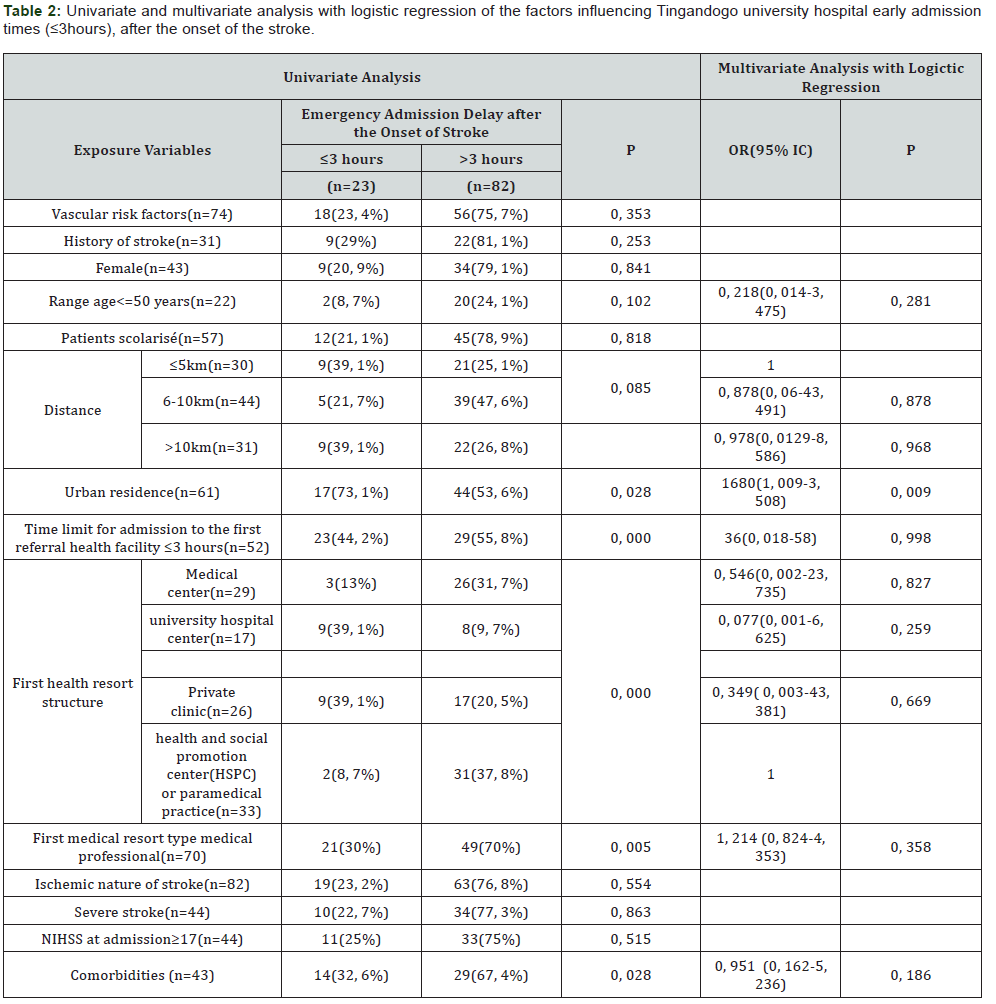

Variables influencing hospital emergency response times: Table 2 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate analyzes of the variables influencing emergency admission delays at Tingandogo University Hospital.

In univariate analysis, the following variables significantly influenced the time to early admission to medical emergencies (≤3hours) after the onset of stroke: urban residence (p=0.028), co-morbidity (p 0.028), the initial use of a medical doctor after the onset of stroke (p 0.005), the initial appeal (direct admission) to the emergency department of the Tingandogo University Hospital (p 0.000), the first-time care service within an early period (≤3hours) after the onset of stroke (p 0.000).

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only urban residence (OR=1.680, 95% CI: 1.009-3.508, p=0.009) was independently associated with an early admission delay to Tingandogo CHU (≤3hours) after the beginning of the stroke.

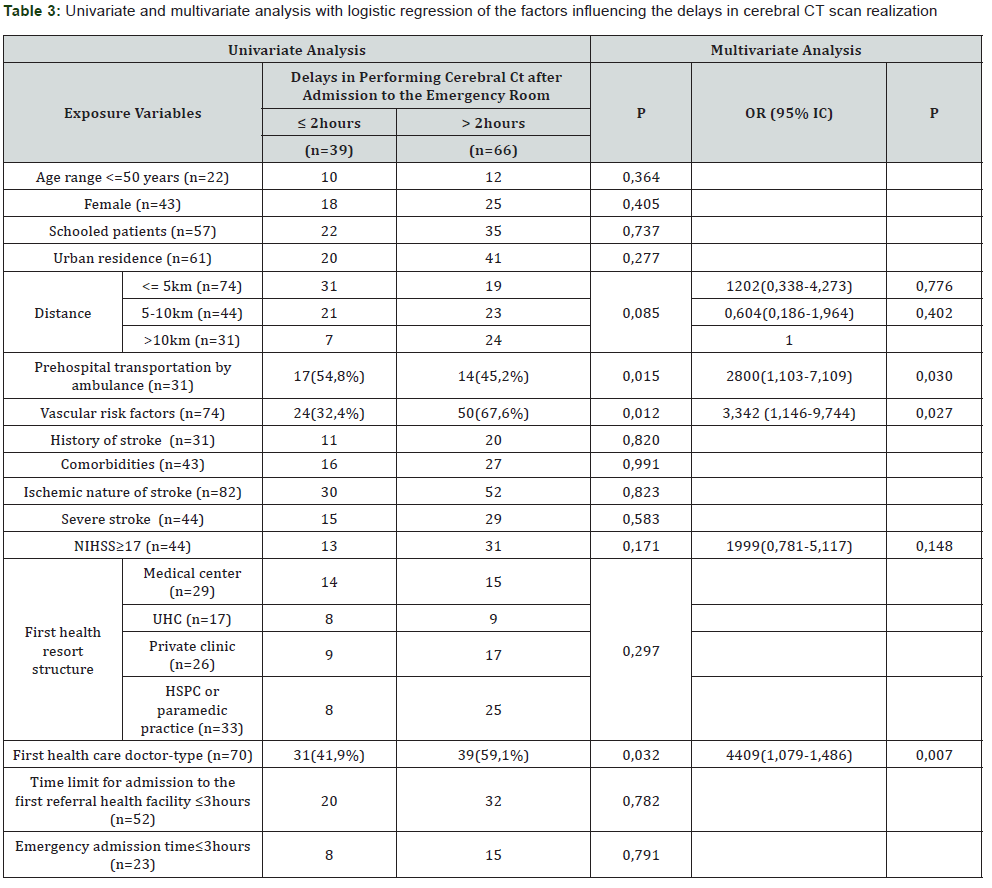

Variables influencing the time required to perform cerebral CT: Table 3 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate analyzes of the variables influencing the time required to perform brain CT after admission to the emergency department.

In univariate analysis, the following variables were significantly associated with an intra-hospital delay in achieving early cerebral CT (≤2hours) after arrival in the emergency department: admission to CHU emergency departments via a personal vehicle (p=0.015), existence VRF in the patient’s history (p=0.012) and initial physician referral after stroke onset (p=0.032).

In multivariate analysis with logistic regression, the existence of VRF (OR=3,342, 95% CI: 1,146-9,744, p=0,027), emergency admission to the CHU via a personal vehicle (OR=2.28, 95% CI: 1.103-7.109, p=0.030) and the initial use of a physician after the onset of stroke (OR=4.409, 95% CI: 1.486-13.09, p=0.007), were independently associated with delayed early completion of cerebral CT (≤2hours) after the patient’s arrival in the emergency room.

Comments and Discussion

About 50% of our patients had recourse in an early time (≤3hours), to a health structure after the beginning of the stroke; however, only 21.6% of our patients were directly admitted to the university teaching hospital emergency department early (≤3hours) after stroke. Similar findings were made in other hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa: 30% in Dakar [9], 32% in Conakry [10] and China with 25% of patients admitted to the SU within 3 hours, following the installation of the stroke [11]. In Western countries, the results are better with nearly 50% of patients admitted to SU within 3 hours of stroke [6, 12,13], and these results are constantly improving. Approximately 37% of our patients received cerebral CT within ≤2 hours after admission to the emergency, which is eligible for IV thrombolysis by activated tissue plasminogen recombinant (t-PA). The reduction of hospital emergency room admission delays after the onset of stroke and the time required to perform cerebral CT after admission to the emergency department is essential to increase the eligibility of the largest number of patients for thrombolysis IV cerebral infarction, only curative treatment of proven efficacy. This treatment makes it possible to reduce mortality, reduce the frequency and severity of post-stroke functional sequelae.

Several factors influencing emergency admission time or SU after stroke have already been identified in European, US and Asian studies [3,5-7,12-16]: pre hospital transportation by ambulance or firefighters, sudden onset of signs of stroke, advanced age or between 65 and 74 years of age, VRF, TIA or prior stroke, atrial fibrillation or coronary heart disease, the existence of a family circle, the female gender, the severity of the initial neurological deficit (NIHSS>15,16 or 17), the disorders of consciousness on admission, the recognition of stroke as a urgency by the patient or his entourage, the stroke of the anterior circulation, a 1st episode of stroke, a suspicion of stroke by the witnesses, the hemorrhagic nature of the stroke. In our study, pre-hospital transportation by ambulance (versus personal vehicle) and the existence of a severe neurologic deficit at admission (NIHSS≥17) were independent factors associated with early admission (≤3hours) in the 1st health facility of recourse after the installation of the stroke. In this, our study is in agreement with the results of the literature [3,5,6,11,12,14].

Indeed, several studies have shown that medical ambulance transport via the emergency medical assistance service (EMS) or by fire fighters, and in particular via a telephone emergency medical regulation system, significantly increases the proportion of stroke patients arriving within the appropriate time for thrombolysis [5,6,8,15]. However, in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) and probably in other large cities in sub-Saharan Africa, pre-hospital transport of patients by ambulances or by fire fighters is still not available and accessible and the emergency medical help services is still embryonic or non-existent. Thus, only 36.5% of the patients admitted early in the 1st health facility of recourse after the occurrence of their stroke arrived there by ambulance, against 63.5% by means of personal transport. At the same time, 11.7% of patients admitted early to the hospital’s emergency department arrived there by ambulance against 78.3% by personal means of transport.

Awareness-raising actions for the general public is needed to improve the early use of a qualified stroke health service. Improvements in the Burkinabe health system and sub-Saharan African countries in general are also required to ensure rapid pre-hospital transport, ideally provided by emergency medical help services or fire fighters, and urgent treatment to the largest number of patients with acute stroke, by creating SU within hospitals. The initial clinical severity of stroke defined by an NIHSS≥17, identified in our study, as an independent early admission factor. In the literature, initial NIHSS>15 or 16 or ≥17 and / or initial impairment of consciousness, were also recognized to have a significant influence on the early admission of patients with acute stroke [6]. Clearly, the clinical severity of stroke is seen more often as a life-threatening threat and encourages patients to seek immediate medical help. In our study, only 41% of patients with an NIHSS≤16 were admitted early into the 1st referral health facility, compared to 61.4% for those with initial NIHSS≥17, which emphasizes that an effort should also be made for patients with clinically moderate stroke. Indeed, all patients should be encouraged to seek medical attention immediately and health education should encourage early hospitalization of all patients with acute stroke, regardless of clinical severity.

We also showed that the urban residence reduced the hospital emergency room admission times. Compared with patients residing in the commune of Ouagadougou, patients from the rural area had long admission delays probably because of the limited availability and accessibility of ambulances, long distances to travel, the poor state of roads, long care path inherent in the health system: initial recourse to the CSPS, then initial transfer to the medical center, sometimes secondary transfer to the Regional Hospital Center before the final transfer to the CHU .Some authors [5,6], however, noted that stroke history, VRF, or co-morbidities among stroke victims most often do not influence emergency admission times paradoxically. This could be explained by an incomplete therapeutic education after the 1st stroke, in particular, the lack of information regarding the existence of a specific treatment in a very early phase.

The minimum intra-hospital patient care period from admission to the emergency department until the beginning of rt-PA administration, referred to as “Door To Needle” (DTN), is evaluated within 60 minutes, in hospitals performing IV thrombolysis in routine practice. This delay includes the time of clinical examinations by the emergency physician, then by the stroke specialist, of realization and interpretation of the cerebral CT, the biological blood tests, the ECG, the time of the various intra-hospital transports, until at the beginning of the fibrinolytic administration. Each of the links in this chain of care can influence the delay in treatment administration [17- 21]. In our context, the median time to perform cerebral CT was the only evaluation of intra-hospital management and is very largely incompatible with IV thrombolysis. In fact, it was 6hours (±20) and only 37.1% of patients received cerebral CT within ≤2 hours after arriving in the emergency room. These very long delays reflect several shortcomings related to the health system and the hospital organization. Among the shortcomings of the health system, we can mention the financial inaccessibility and sometimes geographic inaccessibility of CT for patients. Among the hospital organizational deficiencies, we can cite, the non-inclusion of stroke as a medical emergency accessible to therapeutics, with corollary, at the level of emergency physicians, delays in the clinical evaluation and expression of requests for paraclinical investigations and neurovascular evaluation; at the level of neurologists, delays in neurovascular evaluation and radiologists, delays in the realization and interpretation of cerebral CT examinations.

We find in our study that the existence of VRF, the use of ambulance as a means of pre-hospital transportation, and the initial use of a physician after stroke, were the independent factors associated with early achievement of cerebral CT. Our results are similar to those of Sekoranja et al. [13] in Switzerland who observed that the time required for cerebral CT scanning and the emergency neurologist’s response time were shorter when the patient had been referred by his family, not by the family doctor and when he was transported by ambulance not by his own means of transport. Patients already sensitized on health issues, especially those with VRF or who had seen a doctor after the stroke, naturally had the shortest time to perform CT scans.

Public awareness actions, continuing medical and paramedical training and the creation of an organized network of pre- and intra-hospital stroke care will contribute to the improvement of hospital management and the prognosis of stroke.

Conclusion

Nearly 50% of the patients arrived in the first referral health facility, within ≤3 hours, but only 16% of patients consulted directly with Tingandogo University Hospital’s medical emergencies after the stroke began. The median admission time to Tingandogo CHU was 24hours (±68) and only 22% of patients arrived within 3hours. The median time to perform CT scans from admission to the emergency department was 6hours (±20) and only 37.1% of patients benefited within ≤2hours. Ambulance pre-hospital transportation, initial clinical severity of stroke and urban residence were independent determinants of pre-hospital stroke care pathway, while VRF, pre-hospital transportation by ambulance and initial doctor after the start of the stroke were the determinants of the intra-hospital care pathway. Awarenessraising activities for the general public, medical and paramedical continuing education and the establishment of an organized network of pre- and intra-hospital care for stroke focused on SU, will help reduce the time needed for hospital care and improve the prognosis of stroke.

References

- Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, Kaste M, von Kummer R, et al. (2004) Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of Atlantis, Ecass, and Ninds rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet 363(9411): 768 -774.

- Morris DL, Rosamond W, Madden K, Schultz C, Hamilton S (2000) Prehospital and emergency department delays after acute stroke: the genentech stroke presentation survey. Stroke 31(11): 2585-2590.

- Ossou Nguiet PM, Franck Ladys Banzouzi FL, Matali E, Paggy Dahlia Mawandza PD, Bertrand Fikahem Elleng Mbolla BF, et al. (2015) Unité neurovasculaire de Brazzaville: résultats des 9premiers mois d’activité. Revue Neurologique 171(Suppl 1): A233.

- Kouamé Assouan AE (2015) Communications affichées M 118; 20èmes journées SFN.

- Agyeman O, Nedeltchev K, Arnold M, Fischer U, Remonda L, et al. (2006) Time to admission in acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke 37(4): 963-966.

- Derex L, Adeleine P, Nighoghossian N, Honnorat J, Trouillas P (2002) Factors influencing early admission in a french stroke unit. Stroke 33(1):153-159.

- Fogelholm R, Murros K, Rissanen A, Ilmavirta M (1996) Factors delaying hospital admission after acute stroke. Stroke 27(3): 398-400.

- Mandelzweig L, Goldbourt U, Boyko V, Tanne D (2006) Perceptual, social, and behavioural factors associated with delays in seeking medical care in patients with symptoms of acute stroke. Stroke 37(5): 1248-1253.

- Cissé O, Ba M, Faye AB, Dadah SL (2015) Accessibilité aux soins hospitaliers des patients victimes d’AVC au service de neurologie du CHU de Fann (Dakar, Sénégal), Communications affichées M-016; 20èmes journées de la Société Française Neurovasculaires des, Paris

- Cissé FA, Sangaré L, Camara B, Barry S, Cissé (2015) A Evaluation de la prise en charge des AVC dans le service de neurologie de l’hôpital national Ignace Deen, Conakry, Guinée; Communications médicales affichées, M-107 ; 20èmes journées de la Société Française Neurovasculaires des Paris, Paris.

- Jin H, Zhu S, Wei JW, Wang J, Liu M (2012) Factors associated with prehospital delays in the presentation of acute stroke in urban china. Stroke 43(2): 362-370.

- Lacy CR, Suh DC, Bueno M, Kostis JB (2001) Delay in presentation and evaluation for acute stroke: Stroke time registry for out comes knowledge and epidemiology (S.T.R.O.K.E.). Stroke 32(1): 63-69.

- Sekoranja L, Griesser AC, Wagner G, Njamnshi AK, Temperli P, et al. (2009) Factors influencing emergency delays in acute stroke management. Swiss Med Wkly 139 (27-28): 393-399

- Harraf F, Sharma AK, Brown MM, Lees KR, Vass RI, et al. (2002) A multicentre observational study of presentation and early assessment of acute stroke. BMJ 325(7354):17.

- Kleindorfer DO, Lindsell CJ, Broderick JP, Flaherty ML, Woo D, et al. (2006) Community socioeconomic status and pre-hospital times in acute stroke and transient is chemicattack: do poorer patients have longer delaysf rom 911 call to the emergency department? Stroke 37: 1508 -1513.

- Salisbury HR, Banks BJ, Footitt DR, Winner SJ, Reynolds DJ (1998) Delay in presentation of patients with acute stroke to hospital in Oxford. QJM 91(9): 635- 640.

- Palomeras E, Fossas P, Quintana M, Monteis R, Sebastián M, et al. (2008) Emergency perception and other variables associated with extra-hospital delay in stroke patients in the Maresmeregion (Spain). Eur J Neuro 15(4): 329-335.

- Williams LS, Bruno A, Rouch D, Marriott DJ (1997) Stroke patients’ knowledge of stroke: influence on time to presentation. Stroke 28(5): 912-915.

- Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS (1996) Factors delaying hospital admission in acute stroke: the copenhagen study. Neurology 47(2): 383-387.

- Fernandes D, Umasankar U (2016) Improving door to needle time in patients for thrombolysis. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. p. 5

- Qiang Huang Q, Ma Q, Feng J, Cheng W, Jia J, et al. (2015) Factors associated with in-hospital delay in intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: lessons from china. PLoS ONE 10(11).