Diagnosis and Treatment of Face Pain: A Brief Guide

Egilius LH Spierings*

Department of Neurology, Tufts University Schools of Medicine & Dental Medicine, Boston, USA

Submission: May 08, 2018; Published: May 24, 2018

*Corresponding author: Egilius LH Spierings, Clinical Professor of Neurology & Craniofacial Pain, Tufts University Schools of Medicine & Dental Medicine, 72 Mount Auburn Street, Watertown, MA 02472, USA, Email: spierings@medvadis.com

How to cite this article: Egilius LH Spierings. Diagnosis and Treatment of Face Pain: A Brief Guide. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2018; 7(5): 555724. DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2018.07.555724.

Abstract

Face pain is relatively common and is often thought to be caused by trigeminal neuralgia, while it rarely is. The most common cause is muscular, related to the muscles of mastication in the context of a condition referred to as myofascial temporomandibular disorder (TMD). However, other causes of face pain are possible as well and range in spectrum from continuous neuropathic face pain, sometimes with superimposed stabbing, referred to as painful trigeminal neuropathy, to non-neuropathic or nociceptive stabbing face pain, sinus vacuum, and intranasal contact. A diagnostic approach to these conditions is presented along with a brief description of the treatment options. A face-pain condition not covered here is persistent idiopathic face pain, which used to be referred to as atypical face pain, because the author considers it a non-diagnosis.

Keywords:Face pain; Diagnosis; Treatment; Neuropathic pain; Nociceptive pain; Trigeminal neuralgia; Stabbing nociceptive face pain; Painful trigeminal neuropathy; Myofascial temporomandibular disorder; Masseter myalgia; Sinus vacuum; Intranasal contact

Introduction

Face pain is relatively common but receives very little attention in medical education at graduate as well as post-graduate levels, the latter very much regardless of specialty. Its prevalence in the general population was determined, amongst others, in an epidemiological study conducted in Manchester, England [1]. In the study, randomly selected subjects aged 18 to 75 years and registered with a general medical practice were requested to complete a postal questionnaire.

Of the 3,468 people who were sent the questionnaire, 2,505 or 72% returned it, with 2,290 or 66% returning a fully completed questionnaire, allowing them to be included in the analysis. Chronic orofacial pain, defined as pain present for 3 months or longer, was reported by 7% of the people, with twice the number of women affected than men. The highest occurrence of approximately 10% was found in the age group 36 to 44 years, and the lowest occurrence of approximately 5% in the age groups 18 to 35 years and 64 to 75 years. In general, chronic orofacial pain decreased in it occurrence with age. For comparison, chronic widespread body pain or fibromyalgia was reported by 15% of the subjects, irritable-bowel syndrome by 9%, and chronic fatigue by 8%. From another epidemiological study conducted in the United States, and also for comparison, we know that migraine affects an estimated 12% of the population aged 12 to 80 years and that it is three times more common in women than in men [2].

The treatment of face pain is strongly etiology driven, emphasizing the importance of a correct diagnosis. Often face pain is thought to be caused by trigeminal neuralgia and treated accordingly, medically or surgically. However, the only reason the condition ranks high on the face-pain diagnostic list is because it is generally the only face-pain etiology known to physicians. In addition, causes of face pain other than trigeminal neuralgia are not well established, including the most common one, myofascial temporomandibular disorder (TMD), mostly the work terrain of dentists. The diagnosis of face pain is also hampered by the prevailing opinion that if the pain is stabbing or burning, it is neuropathic in origin, which is, however, by far not always the case. Finally, the cause of face pain is not uncommonly related to the nose or sinuses, which may be recognized by the patient but is often not appreciated by the consulting otorhinolaryngologist.

In this paper, a structured approach to the diagnosis of face pain will be presented, very much based on the experience gained by the author, a neurologist, consulting at the Craniofacial Pain Center of Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts. A face-pain condition not covered is persistent idiopathic face pain, which used to be referred to as atypical face pain, because the author considers it a non-diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Trigeminal neuralgia

The best known face-pain condition is trigeminal neuralgia, with stabbing, jabbing, or lancinating pain in the face as its very hallmark (Figure 1). The pain is unilateral and limited to the innervations area of one of the branches of the trigeminal nerve, usually the maxillary nerve, although occasionally two adjacent branches are involved but rarely the ophthalmic nerve. Sometimes, the stabbing pain occurs with a background of continuous pain and then, it should be the continuous pain, rather than the stabbing, that guides the diagnostic process (vide infra).

A stabbing, jabbing, or lancinating paroxysmal pattern is generally considered an indication of a neuropathic origin of the pain but this is not true and, consequently, stabbing pain can also be nociceptive. We know this, amongst others, from pain in the head in a condition known as stabbing headache, which is probably of migrainous origin because it is often seen in patients with migraine or cluster headache.

A diagnosis of neuropathic pain requires more than just a stabbing, jabbing, or lancinating temporal pattern but also symptoms or signs of nerve dysfunction, and the same applies to pain of a burning nature [3]. The required symptoms or signs of nerve dysfunction concern the sensory response to fine touch in the painful area, consisting of paresthesia, dysesthesia, or allodynia, respectively referring to a tingling sensation, an unpleasant sensation, or pain. Trigeminal neuralgia is a neuropathic pain, caused by demyelination affecting the trigeminal ganglion or the nerve’s root-entry zone, due to multiple sclerosis or vascular casu quo neoplastic compression. Allodynia is what is typically seen in this condition, with fine touch as subtle as a blow of wind, triggering a volley of pain, particularly when affecting so-called trigger zones, which tend to be found especially in the nasolabial fold.Stabbing nociceptive face pain

As with stabbing headache as mentioned, stabbing, jabbing, or lancinating pain in the face can also be nociceptive in nature, representing the facial variant of stabbing headache. It is also unilateral like trigeminal neuralgia but not limited to the innervation area of a particular branch of the trigeminal nerve. As it is not neuropathic in origin, it is not triggered by touch and neither is it associated by fine touch causing paresthesia (tingling), dysesthesia (unpleasant sensation, such as the touch of a finger being perceived as that of an ice pick), or allodynia (pain). Stabbing face pain of neuropathic origin requires imaging of the cerebellopontine angle and treatment with an anticonvulsant, while stabbing face pain of nociceptive nature is treated preventively with indomethacin.

Continuous neuropathic face pain

Neuropathic face pain, that is, pain in the face associated with the symptoms or signs of nerve dysfunction mentioned above, can also be non-stabbing in temporal pattern. Then it is generally continuously present, unilateral in location, and limited in its distribution to one of the divisions of the trigeminal nerve. It does not have to be burning in quality, as is often assumed to be the quality of neuropathic pain when not stabbing, and can be associated with superimposed stabbing pain. The condition is painful trigeminal neuropathy and requires, like trigeminal neuralgia, imaging of the cerebellopontine angle.

Continuous nociceptive face pain

If not stabbing in temporal pattern or neuropathic in origin, face pain tends to be continuous although other paroxysmal patterns than stabbing are possible but they are rare. For example, there is a facial variant of migraine, with severe face pain occurring in attacks that last for a day or days, associated with nausea and sometimes also with vomiting. In further diagnosing continuous non-neuropathic face pain, location of the pain in the face needs to be considered in terms of bilateral versus unilateral and peripheral versus central. This generates the two-by-two table as shown in Table 1, providing the four diagnostic categories of masseter tension, masseter spasm, referred pain from the nose or teeth, and sinus vacuum.

Continuous peripheral nociceptive face pain

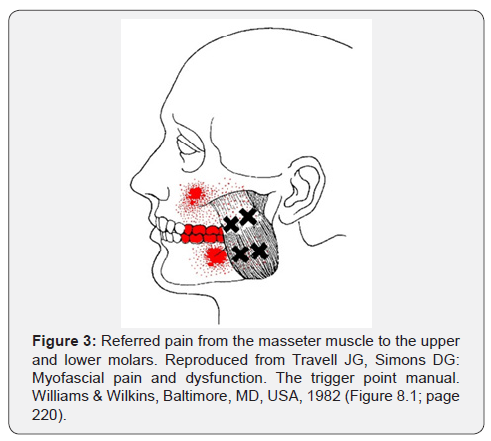

Peripheral face pain, located peripherally in the face, that is, in the jaw(s), involves the muscles of mastication, particularly the masseter muscles in terms of masseter myalgia [4]. When bilateral, it tends to generate a low-level intensity pain and when unilateral, a high-level intensity pain. The bilateral masseter myalgia is generally more described as a discomfort or aches, rather than a pain and can be referred to as masseter tension or the facial variant of (chronic) tension headache (Figure 2). In contrast, the unilateral peripheral face pain is described as pain, often severe, caused by masseter spasm and sometimes associated with stabbing or visible twitching. It may also cause referred pain in the maxillary or mandibular molars, as is shown in Figure 3, erroneously suggesting a dental origin of the pain.

Continuous central nociceptive face pain

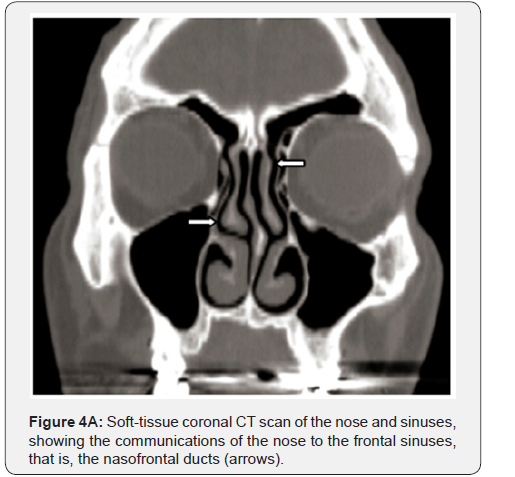

Central face pain, that is, pain located in the area of the nose and/or cheek, in the same way as peripheral face pain, tends to be of a low-level intensity when bilateral and of a high-level intensity when unilateral. When bilateral, it tends to be described as a pressure rather than a pain, like a plunger on the face or a tight mask being pulled to the back (Figure 2). This drawing sensation centrally in the face is caused by under-pressure in the sinuses, a condition also referred to as sinus vacuum, barosinusitis, or sinusitis ex vacuo. It is the result of closure of the passages to the sinuses, particularly the nasofrontal ducts and ostiomeatal complexes, which form the communications of the nose with the frontal and maxillary sinuses, respectively (Figure 4A & 4B). The closure of these passages is generally the result of congenitally narrow passages in combination with inflammation, usually from chronic allergic rhinitis, also causing relatively large turbinates that may well be contacting each other as well as the walls and floor of the nasal cavity (soft contact).

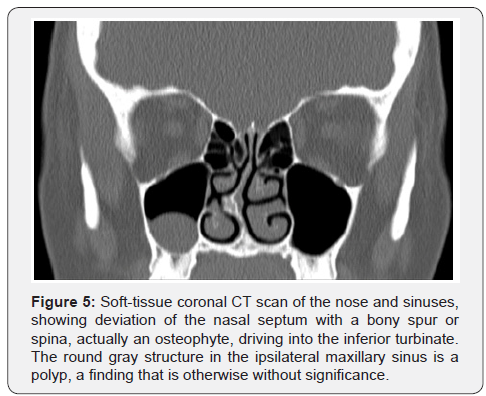

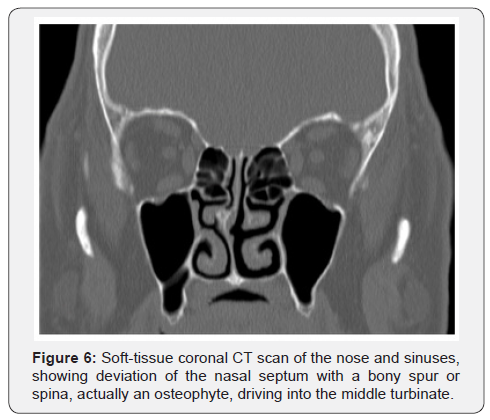

Unilateral central face pain is located in the side of the nose and/or cheek and is either referred from a maxillary incisor or caused by (hard) intranasal contact. The maxillary incisor can be affected by endodontic or periodontal disease and the (hard) intranasal contact relates to a septal spur or spina driving into a turbinate (Figure 5). Usually the inferior turbinate is involved, causing referred pain in the cheek, and sometimes the middle turbinate, causing referred pain in the side of the nose (Figure 6). The inferior turbinate may also cause referred pain in the maxillary teeth, again erroneously suggesting a dental origin of the pain (Figure 7).

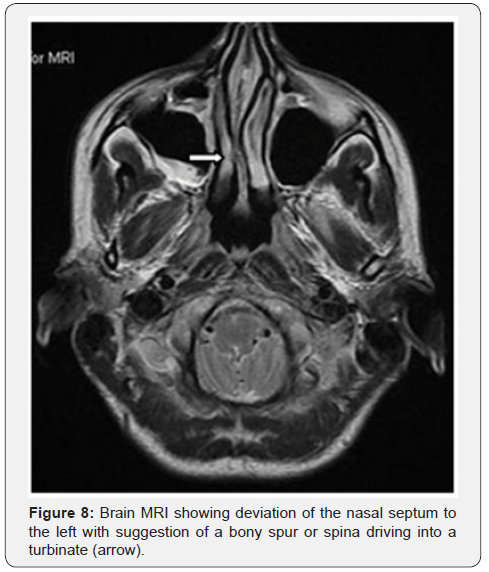

Intranasal-contact pain may also be associated with localized autonomic symptoms of the ipsilateral eye and/or nostril, such as conjunctival injection, lacrimation, or rhinorrhea, often leading to the erroneous diagnosis of cluster headache. However, the typical temporal pattern of cluster headache is missing, that is, attacks that occur daily or almost daily, one to three times per 24 hours, and lasting for 1 or 2 hours. Sometimes, the intranasal contact can be seen on a brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) (Figure 8) but the diagnostic test of choice is computerized tomography (CT scan) of the nose and sinuses with soft-tissue coronal views.

Treatment

Trigeminal neuralgia

The treatment of stabbing face pain of neuropathic origin, that is, trigeminal neuralgia, is extensively covered in the neurological and neurosurgical literature and that of peripheral face pain, that is, masseter myalgia, in the dental, temporomandibulardisorder (TMD) literature [5]. Trigeminal neuralgia can be treated medically or surgically, with the medical treatment being pharmacological in nature, predominantly utilizing anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine. The surgical treatment is generally directed towards the trigeminal nerve or ganglion in terms of destruction or decompression. The non-destructive, decompression approach is usually preferred but it is an invasive procedure that requires an occipital craniotomy. Therefore, the destructive approaches are often attempted first, percutaneous thermo-coagulation or gamma-knife lesioning of the nerve or ganglion. Gamma-knife lesioning is generally preferred because it is more selective in its destruction, that is, it more selectively targets the nociceptive C and A-delta fibers. A feared complication of the destructive procedures is the development of anesthesia dolorosa, although with the more selective, destructive procedures mentioned the likelihood of this complication developing is small.

Painful trigeminal neuropathy

Neuropathic face pain, that is, pain in the face associated with the symptoms or signs of nerve dysfunction mentioned above, can also be non-stabbing in nature and is referred to as painful trigeminal neuropathy. It is generally present continuously, unilateral in location, and limited in its distribution to one of the divisions of the trigeminal nerve, often the second division or maxillary nerve. The pain does not have to be burning in nature, as is often assumed to be the quality of neuropathic pain when not stabbing, and can be associated with superimposed stabbing pain. The treatment is pharmacological with medications that have been shown to be beneficial for neuropathic pain in general, that is, gabapentin, pregabalin, and duloxetine.

Stabbing nociceptive face pain

Stabbing face pain of nociceptive nature, that is, the facial variant of stabbing headache, is treated, as mentioned and like stabbing headache, preventively with indomethacin. However, indomethacin is a potent medication and treatment should only be initiated if the face pain occurs frequently, that is, daily and a good number of times per day. The starting dose is either 25mg four times per day, with meals and at bedtime with some food, or 75mg extended release in the morning with breakfast and 25mg at bedtime with some food. The bedtime dose is often forgotten, resulting in the development of withdrawal headache overnight, causing the patient to wake up in the morning with a dull throbbing pain in the back of the head. If necessary, the dose of the medication can be increased and generally maximum dosages used are 50mg four times per day or 75mg extended release three times per day.

With long-term use of indomethacin, kidney function should be monitored regularly (electrolytes, BUN, creatinine) and the patient should be closely followed for the development of gastropathy. However, gastric symptoms, such as nausea, heartburn, or epigastric pain, do not tend to be prominent with NSAID-induced gastropathy and may be completely absent. Therefore, monitoring for (occult) blood loss may be indicated in the blood (hemoglobin, ferritin) and in the stool (fecal occult blood test). Preventive gastroprotective treatment may also be required and a variety of medications are available for this purpose, most notably histamine-2-receptor antagonists and proton-pump inhibitors, but also medications such as misoprostol and sucralfate. Furthermore, it is prudent to reduce the dose of the medication every so often to see whether the face pain can be controlled with a lower dose or, maybe, can be discontinued altogether.

Continuous nociceptive face pain

The continuous nociceptive face pain of peripheral location, localized in the jaw(s), requires a muscular approach directed at the muscles of mastication, particularly the masseter muscles. In general, it is difficult to get tight muscles to relax and it may require several approaches simultaneously to be successful. The muscles may also be caught in a vicious cycle that may need to be interrupted for the treatment to be successful. This is especially the case with the muscles of mastication, which may be caught in the vicious cycle of bruxism, that is, clenching and grinding. These co-called parafunctional activities are driven by tight muscles and, in turn, make the muscles tight. Oral-appliance therapy is indicated here, with a mandibular appliance used during the day and/or a maxillary appliance used during the night, to protect the teeth from the wear caused by the bruxism and to break the bruxism cycle.

Daily use of heat for 15 to 20 minutes on the muscles is also often beneficial, minimally once per day and, if possible, twice per day, followed by gentle stretching. Formal physical therapy can be applied as well, including massage and ultrasound, as well as acupuncture or acupressure. Relaxation exercises represent another useful modality, utilizing such techniques as biofeedback or autohypnosis. Medications can also be employed, either fast- and short-acting muscle relaxants on an as-needed basis, such as metaxolone, carisoprodol, chlorzoxazone, and methocarbamol, or long-acting muscle relaxants on a daily basis, preferably used once daily at bedtime, such as cyclobenzaprine and tizanidine. Instead of the long-acting muscle relaxants, tricyclics can be used as well, for example, amitriptyline or doxepin when insomnia is also an issue and otherwise the lesser sedating imipramine or nortriptyline. Finally, injection therapy can be applied, either in the form of trigger-point injections with a local anesthetic or injections with botulinum toxin. The latter injection therapy provides much longer-lasting relief, is easy to apply, and is generally tolerated well without side effects, particularly impairment of jaw function.

The continuous face pain of central location, localized in the nose and/or cheek, is treated depending on the nature of the problem. If the pain is bilateral, the culprit is often chronic allergic rhinitis, which can be treated with an anti-allergy nasal spray, such as azelastine or cromolyn, an antihistamine and mast-cell stabilizer, respectively, or with a corticosteroid nasal spray. Regarding the latter, a water-based “aqua” nasal spray is preferred because long-term use is required and is generally better tolerated than an alcohol-based spray, which tends to cause nasal dryness and bleeding.

Unilateral central face pain of rhinogenic origin is caused by intranasal contact that often needs surgical intervention, preferably through an endoscopic, minimally-corrective procedure. However, a decongestant or corticosteroid nasal spray may also be helpful as well as the topical application of a local anesthetic. Relief of the pain by local anesthesia certainly increases the likelihood that surgical treatment of the intranasal contact will have the desired effect but lack thereof does not preclude it. If the unilateral central face pain is of dentogenic origin, a maxillary incisor is the culprit, affected by an endodontic or periodontal condition. An endodontic condition is treated with a so-called root-canal procedure and a periodontal condition, such a periodontal tendonitis, with a non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory analgesic (NSAID). With ether condition, the tooth can also be extracted but that is obviously not the preferred treatment.

Summary

In terms of its temporal pattern, face pain is generally stabbing, jabbing, or lancinating or it is continous; paroxysmal patterns other than stabbing are possible but rare. If stabbing, the pain is either neuropathic or nociceptive, rendering the diagnoses of trigeminal neuralgia and facial variant of stabbing headache, respectively. With neuropathic pain, symptoms or signs of nerve dysfunction are present, such as tingling, unpleasant sensation, or pain upon fine touch, referred to as paresthesia, dysesthesia, and allodynia, respectively.

If non-stabbing, the pain can still be neuropathic and this is the case when it is associated with the above mentioned symptoms or signs of nerve dysfunction, rendering the diagnosis of painful trigeminal neuropathy. With non-neuropathic, non-stabbing pain, location of the pain in the face in terms of bilateral versus unilateral and peripheral versus central needs to be considered to advance the diagnostic process. A peripheral location suggests a muscular etiology, that is, masseter myalgia, in terms of masseter tension (bilateral), also referred to as the facial variant of (chronic) tension headache, or masseter spasm (unilateral). The latter may be associated with stabbing, jabbing, or lancinating pain or visible twitching of the affected muscle. A central location suggests under-pressure of the sinuses (bilateral), also referred to as sinus vacuum, or dentogenic or rhinogenic referred pain (unilateral), originating from a maxillary incisor or caused by intranasal contact, respectively.

Stabbing face pain is treated with anticonvulsants when neuropathic (trigeminal neuralgia) or with indomethacin preventively & when nociceptive (facial variant of stabbing headache). Non-stabbing, neuropathic face pain (painful trigeminal neuropathy) is also treated with anticonvulsants. Non-stabbing, non-neuropathic face pain is treated from a muscular perspective when peripheral, that is, with oralappliance therapy, heat, physical therapy, acupuncture, relaxation exercises, muscle relaxants, tricyclics, trigger-point injections, and/or injections with botulinum toxin. When central and bilateral, it is treated with an anti-allergy or corticosteroid nasal spray and if unilateral, with surgery to relief the intranasal contact or whatever therapy is appropriate for the identified condition of the maxillary incisor.

References

- Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Zakrzewska JM, Lunt M, Macfarlane GJ (2006) The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have a common associated factor? Int J Epidemiol 35(2): 468-476.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD, Reed ML (1992) Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. Relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors. Journal of the American Medical Association 267(1): 64-69.

- Spierings ELH, Dhadwal S (2015) Orofacial Pain after invasive dental procedures: neuropathic pain in perspective. Neurologist 19(2): 56- 60.

- Spierings ELH, Mulder MJHL (2017) Persistent orofacial muscle pain: its synonymous terminology and presentation. Cranio 35(5): 304-307

- Mulder MJHL, Spierings ELH (2017) Treatments of orofacial muscle pain: a review of current literature. Journal of Dentistry & Oral Disorders 3(5): 1075-1080.