Horizontal Conjugate Gaze Deviation Detected in Brain MRI of Two Vestibular Neuritis Patients in the Emergency Room

Do-Hyung KIM*, Soo Jin Yoon, Sang Hyun Jang, Jae Guk KIM, Sung-YeonSohn, Han Na Choi, Jin Ok Kim and SooJoo LEE

Department of Neurology, Eulji University Hospital, Korea

Submission: November 14, 2017; Published: December 20, 2017

*Corresponding author: Do-Hyung KIM, Department of Neurology, Eulji University Hospital, School of Medicine, Eulji University, DunsanSeo-ro 95, Seo-gu, Daejeon 35233, Republic of Korea, Tel: +82-42-611-3431; Fax: +82-42-611-3858; Email: semoxx@naver.com

How to cite this article: Do-Hyung K, Soo J Y, Sang H J, Jae G K, Sung-Yeon S, et al . Horizontal Conjugate Gaze Deviation Detected in Brain MRI of Two Vestibular Neuritis Patients in the Emergency Room. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg. 2017; 6(4): 555694. DOI:10.19080/OAJNN.2017.06.555694

Abstract

Vestibular neuritis is the underlying disease affecting a large number of patients who experience symptoms of dizziness and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Even though vestibular neuritis is often diagnosed by either neurological tests or a vestibular function test, there are few studies of brain MRI in vestibular neuritis patients because brain imaging does not directly aid diagnosis. Here, the authors examine two cases of horizontal conjugate gaze deviation (h-CGD) detected in brain MRI from vestibular neuritis patients visiting the emergency room (ER), and discuss the mechanisms of pathogenesis

Keywords: Vestibular neuritis; Horizontal conjugate gaze deviation; Brain MRI; Emergency room; Nystagmus

Abbreviations: h-CGD: Horizontal Conjugate Gaze Deviation; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; ER: Emergency Room; ENG: Electronystagmography

Introduction

Vestibular neuritis is frequently encountered in cases of peripheral dizziness in the ER. Patients can present with vertigo, contralesional mixed torsional-horizontal spontaneous nystagmus, ocular tilt reaction, postural deviation [1], and autonomic nerve abnormalities [2], without tinnitus or hearing-related symptoms, or neurological symptoms such as weakness,sensory abnormalities, or cerebellar dysfunction. Diagnosis of vestibular neuritis requires neurological tests, various vestibular function tests, and the characteristic finding of nystagmus. However, in patients visiting the ER, it is often impossible to perform all the required vestibular function tests, patients with severe dizziness or postural deviation may not comply with the full suite of neurological tests, and differentiation is often required with central nervous system (CNS) disorders such as stroke. For this reason, imaging examinations such as brain MRI are often used in the ER. Nevertheless, there are few reports on brain MRI characteristics in acute vestibular neuritis patients because imaging tests do not aid diagnosis. Here, the authors report two cases of patients who received neurological treatment after visiting the ER, with the aim of exploring specific finding in brain MRI of vestibular neuritis patients, and discussing the theoretical background for these findings.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 62-year-old male patient with no specific history visited the ER with persistent dizziness that first developed after eating breakfast the day before. The dizziness, which the patient had not previously experienced, developed spontaneously, was persistent, was aggravated by movement of the head or change in posture, and was accompanied by nausea and vomiting. During neurological observations performed in the ER, the patient did not show head tilt, restricted ocular motility, skew deviation, or lateral pulsion.

During central fixation, right-beating mixed torsional- horizontal spontaneous nystagmus was observed; the nystagmus increased greatly on right gaze but decreased on left gaze, and there was no gaze-evoked nystagmus. The spontaneous nystagmus increased when the visual fixation was removed. When attempting smooth pursuit eye movement, the patient experienced saccadic pursuit on right gaze, but was normal on left gaze. Saccadic eye movements were normal in both directions, and in a head impulse test, corrective catch-up saccades were observed when the left horizontal canal was stimulated. In the Frenzel glass test, right-beating spontaneous nystagmus persisted in all positions, and right-beating nystagmus increased after head-shaking. The finger-to-nose test and heel-to-shin test were both normal, but due to severe dizziness, the patient was unable to perform neither tandem gait nor the Romberg maneuver. Other cerebral, motor, and sensory nerve tests were all normal. The dizziness was not accompanied by ear symptoms (e.g. tinnitus, ear fullness, hearing impairment), and the patient showed no pathological reflexes. Blood tests were also normal. Brain MRI (including diffusion weighted image (DWI), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and gradient echo (GRE))was performed to exclude a diagnosis of postural disequilibrium due to acute disease of the CNS.As a result, the patient was diagnosed with left vestibular neuritis with no acute brain lesion.

Case 2

A 58-year-old female patient, who had previously received multiple rounds of neurological treatment for tension headaches, visited the ER with dizziness since waking in the morning. The dizziness had become gradually more severe over time, was aggravated by postural change and head movements, and was accompanied by nausea and vomiting. In neurological examinations, the patient showed head tilt to the right side, but there was no restricted ocular motility, skew deviation, or lateral pulsion. The patient showed left-beating mixed torsional- horizontal spontaneous nystagmus during central fixation, which increased during left gaze and decreased during right gaze. There was no gaze-evoked nystagmus, and the Frenzel glass test showed an increase in nystagmus after the removal of the visual fixation. While attempting smooth pursuit, the patient showed saccadic pursuit during left gaze but was normal during right gaze. Saccadic eye movements were normal in both directions. Corrective catch-up saccades were observed when the right horizontal canal was stimulated during a head impulse test. During the Frenzel glass test, left-beating spontaneous nystagmus persisted in all positions, and left-beating nystagmus increased after head-shaking. Initially, upon admittance to the ER, the patient had difficulty maintaining anstanding or seated position, but actual cerebellar function tests were normal, as were all cerebral, motor, and sensory nerve tests. The dizziness was not accompanied by any ear symptoms; the patient showed no pathological reflexes; and all blood tests were also normal. The patient was diagnosed with right vestibular neuritis, but because of her history with recurrent headaches, the patient also requested brain imaging. A brain MRI was taken, and this test confirmed that the patient had no acute lesions that might cause dizziness.

Results

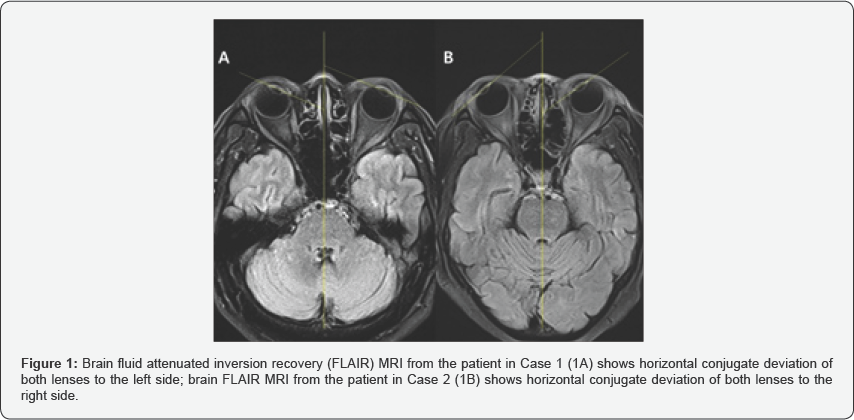

In the two cases presented here, the patients did not show any abnormal findings in the brain MRI that would enable the diagnosis of vestibular neuritis. However, the first patient, who was diagnosed with left vestibular neuritis, showed a horizontal conjugate deviation of both lenses towards the left side in the brain MRI (FLAIR) (Figure 1A), and the second patient, who was diagnosed with right vestibular neuritis, showed a horizontal conjugate deviation of both lenses to the right side (Figure 1B).

Discussion

Both patients were diagnosed with vestibular neuritis based on persistent nystagmus in the same direction even after postural change, with no weakness, sensory abnormalities, cerebellar dysfunction, or pathological reflexes in neurological tests. In general, there are various CNS disorders that can cause dizziness (e.g. stroke, tumor, demyelinating diseases, and infection). However, these diseases could be excluded in both patients based on their brain MRI results; the absence of additional symptoms of CNS infection (e.g. fever, headache, or neck stiffness) during post-hospitalization monitoring; the fact that both patients, despite taking no drugs other than dimenhydrinate and diazepam, experienced spontaneous recovery of dizziness within 1 week post-discharge; and the fact that neither patient showed any new abnormal neurological symptoms after being discharged. Both patients showed an increase in nystagmus in the original direction during the Frenzel glass test, which is characteristic of peripheral dizziness [3,4]. Nystagmus is caused by vestibular neuritis is a result of imbalances in the activation of the left and right semicircular canals, and in the afferent nerve signals entering the brain stem from the left and right labyrinths. Neuritis usually affects the superior vestibular nerve, which innervates the superior and horizontal canals; a decrease in afferent signals from these structures to the nerve stem results in increased activity from their functional counterparts, which are the horizontal and posterior semicircular canals on the healthy side. Therefore, when there is a slow horizontal displacement towards the lesion side due to the horizontal canal on the healthy side, and, simultaneously, a slow torsional displacement towards the lesion side due to the posterior canal on the healthy side, the eyes produce a rapid mixed torsional- horizontal nystagmus towards the healthy side to compensate [5] . This characteristic eye movement can be verified using the Frenzel glass test, but it can only be observed when a patient's eyes are open. Electronystagmography (ENG) can be used to record nystagmus even with the eyes closed; one previous report used ENG in peripheral dizziness patients with a unilateral lesion such as vestibular neuritis, and found that nystagmus increased when the visual fixation was removed on anterior gaze or the gaze in the direction of nystagmus, but that the eyes slowly drifted towards and eventually came to rest on the lesion side [6] . In other words, when vestibular neuritis patients close their eyes, nystagmus increases, but the eyes slowly move towards the lesion side. Because nystagmus in vestibular neuritis and other peripheral dizziness disorders follows Alexander's law, after the eyes have drifted towards the lesion side, nystagmus may be smallest during gaze in other directions. Based on this finding, we might expect that if a vestibular neuritis patient is instructed to close their eyes and wait until a certain time has passed, once the eyes have finished drifting, the patient will be gazing towards the lesion side.

In the two cases presented here, both patients showed a horizontal conjugate deviation of both lenses towards the each lesion side of vestibular neuritis. This type of observation may allow some deductions to be made from imaging examinations. Of course, there are numerous anatomical locations and diseases in the brain that could cause eyeball deviation, but the CNS disorders affecting these anatomical locations present with other specific neurological symptoms apart from eyeball deviation, and such lesions are likely to be identified in brain MRI. Therefore, in cases such as the two presented here, where the patients present with dizziness and nystagmus but without any other neurological findings or abnormalities in brain MRI, the observation of h-CGD in both eyes in brain MRI can be considered a pathophysiological feature of vestibular neuritis and distinguish it from a CNS disease. This needs to be investigated further in studies with more patients.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflicting interests and none of them are supported/funded by and drug company.

References

- Choi KD, Goh EK (2008) Vestibular neuritis and bilateral vestibulopathy. J Korean Med Assoc 51(11): 992-1006.

- Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, et al. (2017) Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 156(3):1-47.

- Abadi RV (2002) Mechanisms underlying nystagmus. J R Soc Med 95(5):231-234.

- Bergstedt M (1988) Vestibular and non-vestibular nystagmus in examination of dizzy patients. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 455: 14-16.

- Strupp M, Brandt T (2009) Vestibular neuritis. Semin Neurol 29(5): 509-519.

- Rudge P, Bronstein AM (1995) Investigations of disorders of balance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 59(6): 568-578.