To Care or To Cure, that is the Question…. Alzheimer’s Disease and Palliative Care

Martinelli E1*, Carlucci R1, Sapone P1, Padulo F1, Mondino S1, Gareri I2, Gareri P3, Maina E4, Natale C5, Foti D5, Crucitti M8, Gelmini G6 and Cotroneo AM7

1Geriatrician - Complex Geriatric Unit Maria Vittoria Hospital Turin, Italy

2Doctor - Catanzaro Italy

3Geriatrician - ASP Catanzaro, Italy

4Nurse - Complex Geriatric Unit Maria Vittoria Hospital Turin, Italy

5Psychologist

6Directior Langhirano Medical District Parma, Italy

7Director Complex Geriatric Unit Maria Vittoria Hospital Turin, Italy

8Psychiatrist ASP Reggio Calabria, Italy

Submission: December 18, 2023; Published: January 26, 2024

*Corresponding author: Martinelli E, Geriatrician, Complex Geriatric Unit Maria Vittoria Hospital Turin, Italy

How to cite this article: Martinelli E1*, Carlucci R1, Sapone P1, Padulo F1, Mondino S, et al. To Care or To Cure, that is the Question…. Alzheimer’s Disease and Palliative Care. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2024; 7(5): 555723. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2024.07.555723

Abstract

Objective: Compare the occurrence of hospitalization in the preceding 12 months among frail, vulnerable and non-frail older adults attended at primary health care units.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 298 older adults who attended primary health care units in Santos, SP, Brazil, divided into three groups classified according to the Edmonton Frailty Scale: non-frail (n=161), vulnerable (n=78) and frail older adults (n=59). To achieve the study aims, we analyzed information regarding the occurrence and number of hospitalizations reported by older adults, and/or their companions, in the preceding 12 months.

Results: The Chi square test showed a significant difference in hospitalizations (p =0.016), with higher frequency among frail older adults (n=11; 18.6%), followed by vulnerable (n=11; 14.1%) and non-frail older adults (n=10; 6.2%). A significant difference was also observed regarding the number of hospitalizations (p =0.038), where one report of hospitalization was more common among frail (n=8; 13.6%) and vulnerable older adults (n=10; 12, 8.0%) than non-frail older adults (n=7; 4.3%).

Conclusion: Hospitalization prevalence was low in the three groups studied, though it was a more frequent outcome among vulnerable and frail older adults, particularly the latter, than for non-frail older adults.

Keywords: Dementia; Oncological Disease; Neurocognitive Disorders; Mammography; Anesthesia

Abbreviations: CDCD: Centre for Cognitive Disorders and Dementia; BTCP: Break Through Cancer Pain

Opinion

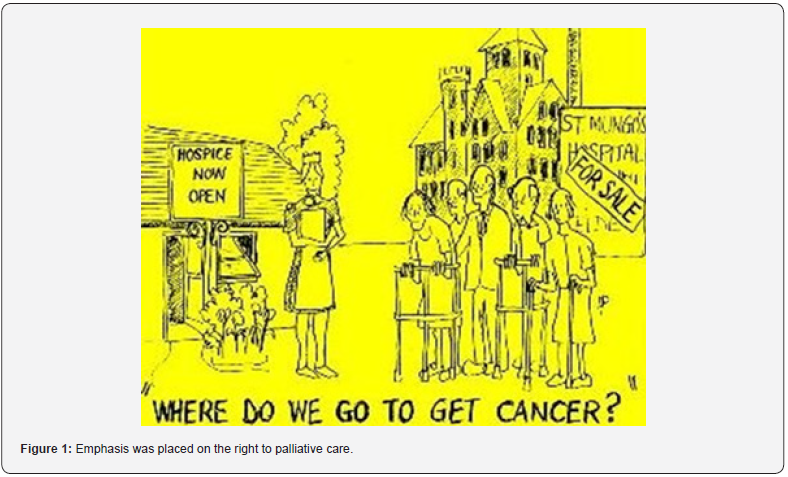

Dementia is a disease of our time and it is considered a global priority in the field of public health; it is a degenerative, progressive, irreversible pathology, for which, at the moment, there are no “disease modifying” therapies capable of to change its evolution and the perspective of the patient and family-care-givers. The numbers of this epidemic are known to everyone: according to the WHO, there were 47 million people affected by dementia in 2015 in the world, with an expected increase to 75 million by 2030. Again according to the WHO, dementia is the seventh cause of death [1] (Figure 1).

In Italy, with Law 38 of 15 March 2010, emphasis was placed on the right to palliative care which, however, is still very oncocentric. For Azheimer’s disease and dementia an economic allocation was established by Law number 178 ( paragraph 330, 331, 332) only on 30 December 2020 [2].Provocatively in this short writing we want to highlight how there is a close parallelism between oncological disease and neurocognitive disorders and underline how the needs are similar, but the attention and resources have different weights. The elderly population is exposed to a greater risk of developing oncological diseases and neurocognitive disorders, however the approaches are clearly different in the two dimensions. Taking the history of oncology pathology as an example, let’s try to draw a parallel with dementia-related diseases.

Screening: There is currently a wide debate on the real benefit of carrying out screening to identify patterns of cognitive deterioration in the preclinical and/or prodromal phase. How could it be conducted? Through a clinical evaluation carried out by whom? By primary care medicine (GP) and in what way? Are the tests used in basic medicine so fine as to intercept prodromal and preclinical cases? It can be carried out through laboratory tests (serological tests seem to be promising), but they pose a risk, and are not as advantageous from a cost-benefit point of view, as for example the test for fecal occult blood or the PAP test, or the mammography as in colorectal and female cancer screening. And are the costs sustainable, given that at the moment there are no effective “disease modifying” treatments? [2].

Thanks the prevention and control of risk factors due, also, to the improvement of living and environmental conditions and the great development of medical technology and science, there has been a notable increase in life expectancy, but also an increase in the incidence and prevalence of diseases age related. Probably, for the development of cognitive disorders, much is known about “natural prevention”, just think about the control of cardiovascular risk factors, the modification of lifestyles, both in young adulthood and in senile age, and, as Candido, by Voltair, would argue, in the best possible world, the “maximum” of preventive or almost preventive action has probably been achieved. However the process of the development of neurodegenerative pathologies is complex and chronologically distributed in stages, so prevention can probably no longer be only natural with correction of some risk factors, but must be proactive with drugs or “therapeuticpreventive” interventions.

Diagnosis is a fundamental stage in every pathology: it is the moment in which an indelible mark and a life and illness trajectory is assigned to a man and/or a woman and her family members. In a treatment and progression process in which the pathology is one-way, it is essential to activate a treatment process with drugs which, at the moment, are not disease modifying, but which have a role in slowing down the progression and preserving in some way, the functional aspect, and also give a caring perspective. A palliative mentality is needed (as present in oncological diseasessimultaneous care) to remodulate the disease trajectory, which is not the acceptance of a slow and progressive decline, but it is a reprogramming, a redesign, a search for a new purpose and path for the patient and the group of people who will increasingly take care of him. The alliance between healthcare workers, patients and family members and care-givers becomes essential.

At the present time, in this kind of neurological degenerative diseases, the objectives are different, it is no longer healing, but rather taking care of, maintaining what is the existential, physical and human core of our patient [3]. Therefore, even if the drugs do not cure the pathology, they have the meaning of maintaining the cognitive aspects and autonomy as much as possible, of maintaining a meaning to the treatment. It is important to take charge of the patient and the family in the management, which always involves gratuitousness, caritas, a laborious dedication given by the family members that increases with the passage of time. It is a caring that sees the progression of the disease and the inexorable change of one’s spouse, of one’s parent who is no longer him but is always him. Support for family members is fundamental especially in preparing for the more advanced stages and sharing the end-of-life journey.

Dementia clinics in Italy (CDCD-Centre for Cognitive Disorders and Dementia) tend to follow patients as long as there is therapy, be it for the control of behavioral disorders or for the prescription of I-AcE and memantine; but when there is no longer any indication for therapy, the patients and care givers go from routine check, periodic appointments to nothing: so what happens to them afterwards? What happens to these groups of patient-care-givers? who will take care of them? Fortunately, the CDCD centers present a long term vision and as previously stated it is necessary to start a perspective vision immediately, that is, to prepare to face the advanced stages of the disease with a communication of what will happen and with a start of everything that will be able to support the aftermath , i.e. the welfare, management, medical-legal and psychological aspects.

It is also important to set up a shared care plan to allow the patient self-determination, in the phases in which he is still able to decide for himself, and also relieve family members from the burden of deciding for their loved one in moments of complex and difficult stages of disease progression. We must not find ourselves unprepared when faced with thorny problems, such as artificial nutrition, the onset of acute events that could require hospitalization - delirium, infections, the difficulty of management at home, when the care-giver has been worn out for years of care, or elderly and sick. The vision in these crucial and painful phases, which often generate remorse, further stress and discomfort for the patient and those who care for him, is not one of acceptance of the inevitable end and abandonment, but rather of remodulating and accompanying in this moment of possible separation with a wealth of awareness acquired in the long journey of care and assistance and shared management in the most extreme phases of illness, so that there is an understanding and acceptance of the separation.

Often in the terminal stages, caregivers express feelings of guilt due to the uncertainty of having done everything possible, of having chosen the best care setting, of having looked after their loved one as best as possible, of not having “ghettoised” him or her in a facility for the sick- hopeless terminals. It is essential to prepare and activate services that can support at home or in more comfortable residential settings. Another critical moment is the aftermath, it is filling the void: after the diligent, long care of one’s loved one, who absorbed a good part of the energies of a part of existence, with the days following the same routine, the thoughts, the worries, joys, probably few, we need to face the new horizon which is probably partly a relief, but partly an abyss in which we need to reorganize and rethink our lives, find a new purpose and somehow keep alive the memory of who no longer had memories.

A further parallel between oncological disease and dementia is pain and behavioral disorders, which are the symptomatic cohort that often puts the care-giver relationship and sometimes the medical management into crisis: the therapy is not only medical, but has a behavioral-environmental approach , as in cancer pain, it is necessary to evaluate the causes that can trigger these symptoms and set up a basic therapy that contains the symptom to guarantee a better quality of life, adequate night’s rest and functional, but also emotional, autonomy (think to the apathy and apathy typical of BPSD, but also the sentimental “anesthesia” sometimes caused by neuroleptics or “emotional blunting”).

Sometimes, as with Break Through Cancer Pain (BTCP), there are behavioral “attacks”, which are not delirium superimposed on dementia, which require as-needed therapy which often must be managed by care givers with, sometimes rupture of that fragile balance with possible hospitalization and institutionalization or improper therapies [4]. The parallelism between the history of oncological disease and dementia is a provocation since dementia-related pathologies have their own individuality and autonomy, but all this is aimed at underlining that people die from dementia, that it is a disease that leads to a stage of terminality that must be addressed not in the urgent-emergency phases, but rather it is a path that must be set from the early phases, where the remodulation, the rethinking of a “care” care perspective is fundamental, rather than “cures”, at the present time, unfortunately. All this does not take away hope or make important attempts to find an effective cure useless and futile, but in the face of uncertainty we need to find certainties that must be sought in man and humanity, not just in science.

As Professor Trabucchi claims, complexity must be the interpretative key, sectoral actions do not lead to real advantages, the role and the importance of networks, connections and environmental conditions is fundamental [5]. It is essential to design a well-being system that is comprehensive and above all attentive to the most vulnerable, including the elderly and those suffering from dementia: they do not benefit from unrelated aid, but from interventions without gaps, from concrete actions and stable bonds, seasoned with humanity and sharing, with a strong generational alliance. There is a need for relationship, for contact, for humanity that characterizes the life and essence of every human being, even when the mind seems to no longer be there and it seems impossible to establish contact, but as is present in the geriatric-palliative culture, there is always the possibility of remodulating the therapeutic strategy, of remodulating the communication channels to maintain the core of humanity, affection and dignity that the patient possesses.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more.

W. Shakespeare Macbeth soliloquy

Yet the feeble candle continues to illuminate the dark night.

References

- (2020) WHO. The top 10 causes of death.

- Leonardi M (2009) Definire la disabilità e ridefinire le politiche alla luce della Classificazione ICF. ICF e Convenzione ONU sui diritti delle persone con disabilità, Erickson.

- Voumard R, Rubli Truchard E, Benaroyo L, Borasio GD, Büla C, et al. (2018) Geriatric palliative care: a view of its concept, challenges and strategies. BMC Geriatr 18(1): 220.

- Lorenz K, Joanne L, Sydney MD, Lisa RS, Anne W, et al. (2008) Evidence for Improving Palliative care at the end of life: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 148(2): 147-159.

- Trabucchi M (2022) Aiutami a ricordare. La demenza non cancella la vita. Come meglio comprendere la malattia e assistere chi soffre. San Paolo Edizioni.