Adapting Group Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for Dementia to Egyptian Culture (CST-Egy)

Alia Adel Saleh1, Ola Osama Khalaf1, Reham Kamel2, Sandra Wassim Elseesy2, Osama Refaat3, Noha Ahmed Sabry3 and George Tadros4*

1Psychiatry, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt

2Psychiatry, Lecturer of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo, Egypt University, Egypt

3Psychiatry, Professor of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt

4Professor of Old Age Psychiatry & Dementia, Aston Medical School, Aston University, UK, Clinical Lead of American center of Psychiatry & Neurology, UAE

Submission: August 08, 2022; Published: August 24, 2022

*Corresponding author: George Tadros,Professor of Old Age Psychiatry & Dementia, Aston Medical School, Aston University, UK, Clinical Lead of American center of Psychiatry & Neurology, UAE

How to cite this article: Alia Adel S, Ola Osama K, Reham K, Sandra W E, Osama R, et al. Adapting Group Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for Dementia to Egyptian Culture (CST-Egy). OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2022; 7(1): 555701. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2022.07.555701

Abstract

Objective: The study aimed to provide a culturally adapted version of the group CST and to test its acceptability and applicability.

Method: A Delphi study design in which 30 staff members received a CST training workshop and 6 patients with mild dementia received a 14-session pilot CST group that was followed by staff and patient acceptability survey. Results of the survey, barriers and challenges were presented in a Delphi group. Cultural adaptation to CST form and content were made through a Delphi consensus.

Results: CST-Egy was acceptable to 96.7 % of staff members and 83.3 % of patients surveyed. Patient showed a significant improvement in their cognitive assessment scores after CST (p=0.026). Barriers identified and modified items included increased carer burden, frequency and duration of CST sessions, effect of educational level and illiteracy, Egyptian cultural and socioeconomic considerations.

Conclusion: CST-Egy is acceptable and feasible among health care professionals and patients. More research is needed to measure its efficacy in Egyptian culture.

Keywords: CST; Egypt; Cognitive Stimulation; Cognitive Disorders; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; Multidisciplinary Cognitive Rehabilitation Programme; Dementia; Elderly people; Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5; Anti-choline Esterase Inhibitors

Introduction

Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) is a well-established, evidence based therapeutic intervention for people with dementia that offers a wide range of activities that provide stimulation to a wide range of cognitive domains such as thinking, concentration, memory and social skills. It is usually provided in a group setting [1-2].

Previous research has shown consistent evidence that CST provides benefits for cognition and quality of life in people with mild to moderate dementia and is cost-effective [3-4]. CST was the only non-pharmacological intervention with sufficient evidence to warrant recommendation by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [5]. NICE guidelines for dementia care propose that ‘People with mild-to-moderate dementia of all types should be given the opportunity to participate in a structured group cognitive stimulation programme and should be offered irrespective of any drug prescribed for the treatment of cognitive symptoms of dementia’ This recommendation was reinforced by the World Alzheimer’s Report [6].

The initial CST programme is constituted of 14 sessions of a wide range of activities that include discussion of past and present events, physical exercises, word and number games, puzzles, music and social activities. Each session is usually run by a trained health care professional in a group of 5 to 8 people with Dementia, once or twice weekly, for around 45 minutes [7]. Maintenance CST (MCST) which is a longer form of CST, was developed to investigate whether benefits of CST could be retained. Research showed continued improvements to quality of life and activities of daily living without significant benefit to cognition except when combined with Anti-choline Esterase Inhibitors (ACHEIs) [8-9].

An individual form of CST programme (iCST) that was designed to be delivered by a family member or carer on individual basis, has also been evaluated [10]. Results showed improvements in the caregiving relationship from patients’ perspective with no change in cognition and quality of life [11]. The effectiveness of CST has also been supported by a range of systematic reviews, which indicated benefits to cognition, quality of life and wellbeing. The authors highlighted the importance of the group format when compared to individual therapy, arguing that participants are encouraged to interact better in the group setting [12-13].

Another recent systematic review of qualitative research that aimed to explore experiences of group interactions in CST and MCST groups identified six themes: ‘benefits and challenges of group expression’, ‘importance of companionship and getting to know others, ‘togetherness and shared identity’, ‘group entertainment’, ‘group support’ and ‘cognitive stimulation through the group’ that may offer therapeutic advantage to the group format [14].

CST was initially developed in the United Kingdom, and currently widely offered in the NHS. However, lately, there has been an increase in the need of the examination of the feasibility of its application in other countries. Yamanaka et al. translated CST into Japanese language and also modified its contents to suit Japanese culture (CST-J) and performed a single-blind randomized clinical trial to examine its efficacy. The intervention group in Japan that participated in CST-J also showed significant improvements in cognitive function and quality of life as compared to the control group. The study concluded that CST may show promising benefits for people with dementia from cultures other than British. Yet, it stressed the importance of sufficient modification to the content to render it culturally appropriate before adopting CST in a different cultural setting [15].

Another study using CST was conducted in Nigeria and Tanzania. Since it was a pilot study, the sample was not large enough to indicate significant changes in cognitive functioning but the study has proven feasibility of CST in Africa which further suggests the adaptability of CST in different cultures. A similar study conducted in rural Nigeria showed that CST was feasible in this setting, although adaptation for low literacy levels, uncorrected visual and hearing impairment and work and social practices was necessary [16-17].

A pilot study in South India for culturally adapted CST showed a good level of acceptability and feasibility as the adapted program was found to be acceptable, enjoyable, and constructive by participants and carers [18]. In a study investigating the cultural appropriateness and feasibility of CST in Hong Kong in which 30 patients and their carers were enrolled, 54% of participants achieved outcome of no cognitive deterioration, and 23% showed clinically meaningful improvement. Family caregivers and group facilitators expressed good acceptance of CST, with a low attrition (13%) and high attendance rate of CST-HK sessions (92%) [19]. In another study conducted in Brazil to examine CST implementation difficulties and cultural considerations, individual interviews and focus groups were conducted with patients with dementia their carers and health professionals. The results indicated that CST was appropriate for use in the Brazilian population, with some cultural adaptations [20].

A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of 11 different psychosocial interventions for dementia in 6 low to middle income countries showed that evidence for improving both cognition and quality of life was found in CST and Multidisciplinary Cognitive Rehabilitation Programme (MCRP). CST appeared to be the most readily implemented intervention in these countries compared to other interventions [21-22]. Egypt is one of the largest countries in the Middle East with an estimated population of more than a hundred million, 4.22 % of them are above the age of 65. Life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 72.5 years. (Egypt Demographics Profile, 2018) [23]. Recent systematic reviews conducted to examine the prevalence rate of Dementia among elderly Egyptian population reported a prevalence rate ranging from 2 to 5 % that tends to be higher in older age groups, illiterate subjects and institutionalized elderly. The studies confirmed the importance of including therapeutic services for dementia in the health care system and promoting the awareness of dementia among the public [24-25].

Therapeutic interventions for dementia in Egypt are limited to cognitive enhancing medications, and psychoeducation of the carers as CST is not practiced in Egypt as yet. Possible reasons for this are the educational and cultural differences of the Egyptian population which render this therapeutic program difficult to apply without adaptation as well as the domination of the medical models which are more acceptable than non-pharmacological models. Therefore, patient and staff acceptability to CST and feasibility of its application need further exploration.

Our research team translated and culturally adapted the manuals of this therapeutic program to make it suitable for use in Egyptian patients suffering from dementia [7,26]. Cultural adaptation of the program involved replacing or modifying the original program group activities, exercises and games that were designed to suit western educational and cultural background with other activities that are more suitable, familiar and preferable to Egyptian population.

Methods

The process of adaptation was based on staff and patient acceptability measures, a pilot CST group for measurement of feasibility, that was followed by a Delphi group consensus. We also followed the evidence-based guidelines for cultural modification of the intervention that was published by the authors [27].

Translation and Adaptation of the CST Manual

The authors were granted permission from Professor Aimee Spector and her team for translation and cultural adaptation of the manual. The translation was done by an accredited translation centre and was reviewed. A one-day CST training workshop was conducted in Cairo University by a UK based Clinical Psychologist. The workshop was attended by 35 participants that included the research team, old age psychiatrists, general psychiatrists, psychologists, geriatric medicine physicians, family physicians, neurologists and a geriatric nurse. All participants were clinically practicing in the field of dementia and showed particular interest in CST training.

Staff Acceptability

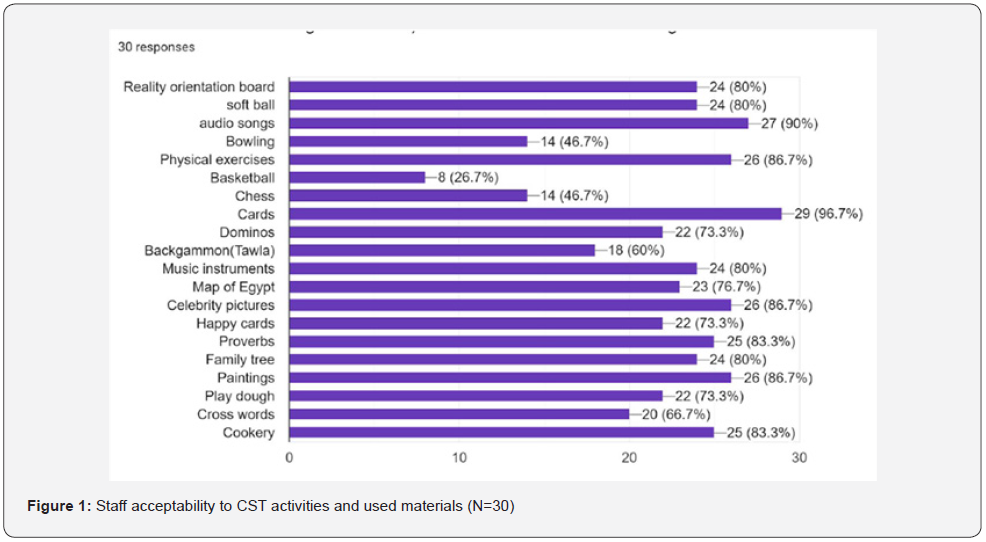

The participants were asked to answer a semi-structured online survey that involved a group of questions measuring staff acceptability to CST program and the feasibility of its application (Table 1). We received the answers of 30 participants. Participants were asked to choose between agree and don’t agree or a number of suggested choices. participants were also asked to rate the activities, games, exercises that were used and provide alternatives to the ones that are not suitable.

N.B., We received 29 responses from staff members in questions 4, 6, and 9.

Patient acceptability and feasibility of CST

To measure patient acceptability and feasibility of application of the programme among Egyptian patients, a pilot CST group was conducted. After obtaining the necessary ethical approval the research team invited 18 patients diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or mild dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) [28] in the memory clinic of Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University to participate in a pilot CST group. Ten patients refused to participate, reasons for refusal included the following (4 patients/carers not convinced with benefit of intervention, 5 patients/carers refused due to family/work obligations, and 1 patient refused due to his physical health status). Only 8 patients participated in the pilot group and gave informed consent, 6 patients completed the CST program (attended at least 12/14 sessions) and 2 patients dropped out early (reason for drop out were inconvenience of the group time).

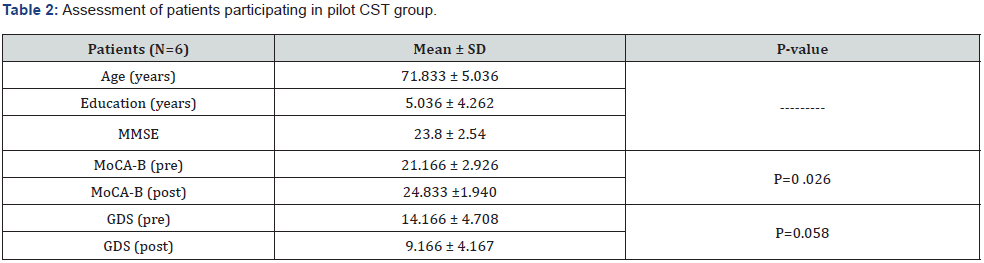

Initial assessment of patients included through history taking, present mental state examination and cognitive testing. The following tests were applied, Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) [29], Montreal Cognitive Assessment- Basic (MoCA-B) [30-31], Geriatric Depression Scale -Short Version (GDS-15) [32]. Patients scoring less than 10 in the MMSE were excluded. Patients suffering from severe depression, anxiety, agitation, uncorrected visual or hearing impairment or unstable general condition were excluded. Patients with mild forms of dementia and MCI were preferred in an attempt to allow their participation effectively in rating the adaptations done to the group sessions and in answering the patient acceptability survey (Table 2).

MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA-B=Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic, and GDS=Geriatric Depression Scale.

Program Delivery

The 14-session program was delivered by an old age psychologist and a resident psychiatrist following the previously mentioned CST manual volumes 1 & 2. The sessions were held in a wide, comfortable, quiet, well illuminated and ventilated room in the Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine hospital in Cairo, Egypt on a once weekly basis, each session lasted for 45 minutes in the period from October to December 2019. Following the completion of the group, patients were asked to complete a patient acceptability survey that included the same questions that were used in the staff acceptability survey. MoCA-B and GDS tests were reapplied to measure possible improvement in cognition and mood.

Delphi Consensus

Staff members who attended the CST training workshop and participated on the online survey were invited to attend a CST round table discussion that was scheduled as a closed session in the 13th Kasr Al Ainy Annual International Congress. Twenty participants attended the meeting in addition to the research team. The participants represented different medical and health care specialities providing care for the elderly in Egypt including psychiatry, neurology, psychology, nursing, geriatric and family medicine in Cairo University, Ain Shams University, Bani Swef University, Helwan University and Behman hospital from the private sector.

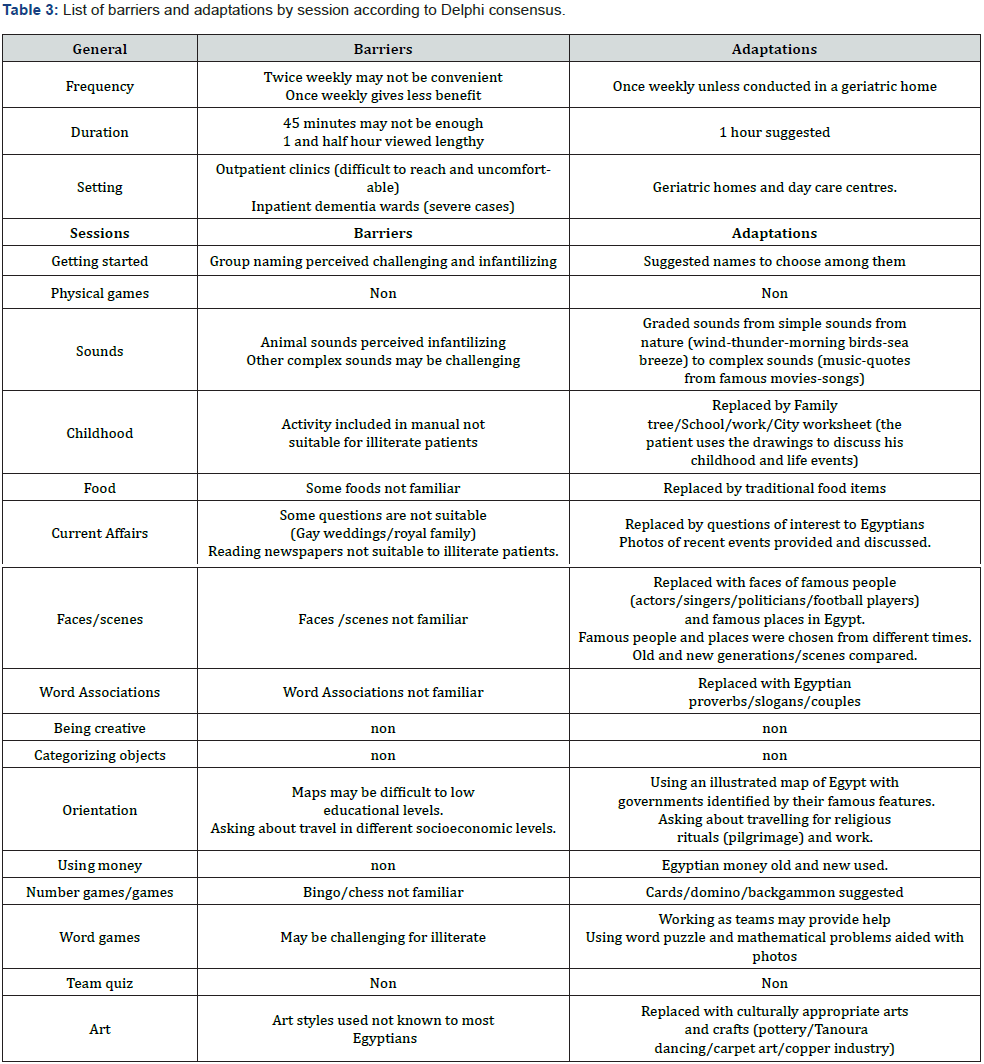

The results of the staff and patient acceptability surveys were presented. Barriers and facilitators were discussed. The suggested adaptations were presented and discussed. Adaptations discussed included adaptations to the general form of the program (i.e. frequency and duration of sessions) and content that was reviewed session by session (Table 3). Participants were asked to vote on the adapted items and/or provide alternatives till consensus was reached.

Ethical Approval and Consent

Ethical approval was obtained through the ethical committee of Cairo University (Rec Application: N-132-2018). An informed written consent was taken from the participants. Data was coded and secured on a computer with no access except for the principal investigator and coinvestigator.

Data Analysis

The acceptability surveys were created by the authors using Google forms that were emailed to participants on their personal emails. A printed version of the survey was made also available in case participants were unable to provide answers by mail. Patients who found difficulty in reading or understanding the survey questions were aided by the resident or psychologist in charge. The results were received and further analysed. Patients data was expressed in terms of mean±SD and range. Patients scores in MoCA-B and GDS-short were compared before and after CST using paired t-test. A probability level of less than 5% was considered significant.

Results

Staff Acceptability Results

The results of the staff acceptability survey (Table 1) showed that 96.7 % of staff agree that patients would like to participate in CST while; 90 % agree that carers would want patients to participate in CST. All staff members expected that CST would improve patient’s cognition while; 96.6 % of them agreed that CST may improve patient’s mood. However, 53.3 % of staff members expected a high drop-out rate. Though, 79.3 % agree that the activities are suitable for patients with higher levels of education, 76.7 % agree that the activities are also suitable for illiterate patients and patients with low education. Once weekly session was suggested to be more suitable for patients 66.7 % versus 33.3 % who recommend two sessions per week. 41.4 % of staff members recommended a one-hour session, while 34.5 % recommended a 45 minutes session and 24.1 % recommended a longer session of one and half hour. The majority of the participants (73.3 %) believed that outpatient clinics and day care centres are the most convenient settings, 23.3 % thought that residential facilities are more convenient and only 3.4 % thought that hospital inpatient wards are convenient (Table 1). Rating of the different activities used showed that basketball (26.7 % agree), chess (46.7% agree), and bowling (46.7%) were viewed less suitable to the Egyptian population compared to other activities.

Patient Acceptability and feasibility of CST

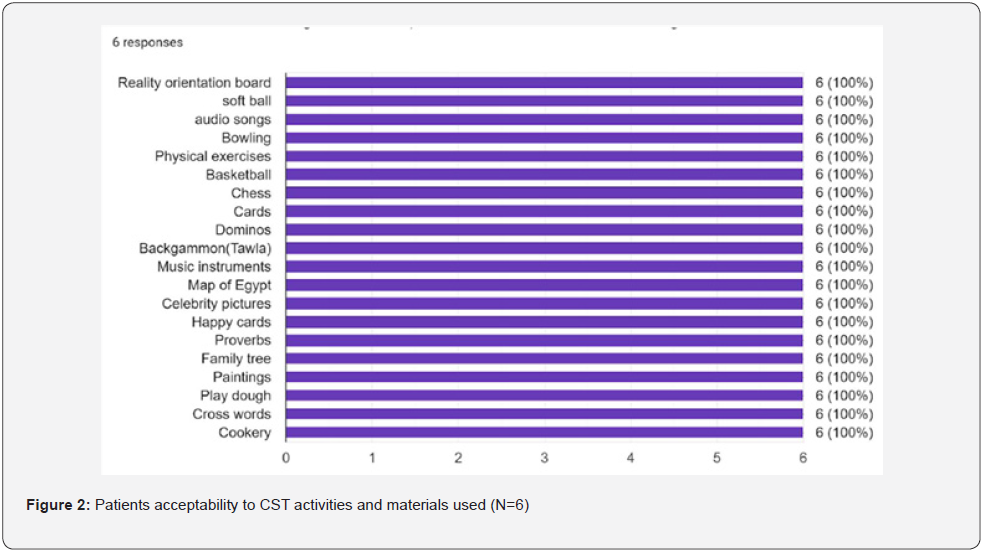

The results of the patient acceptability survey showed that the vast majority (83.3 %) would like to participate in CST, and believe that their carer will be happy to take part. They (83.3%) did not expect a high dropout rate. All patients agree that CST could improve their cognition and mood and that the activities are suitable for them. The majority of the participants (66.7%) recommend two sessions per week, while 33.3 % of patients felt one session per week would be enough considering transportation challenges. Half of the participants recommend an hour session, while the other half recommend a 45 minutes session. Most of patients (66.7 %) thought that outpatient clinics and day care centres are the most convenient settings. All patients viewed the activities used as suitable (Table 1 & Figure 2) [Insert Figure 2: Patients acceptability to CST activities and materials used (N=6)].

Discussion

Well-established psychotherapeutic interventions in one culture may become ineffective when applied in different cultures due to implementation difficulties and/or cultural inappropriateness. Accordingly, pilot and small-scale studies are always required before large scale application. Cultural appropriateness is important for creating meaning and motivating engagement in the intervention, particularly for older adults [33].

In the process of adaptation, the following barriers were identified and addressed whenever possible, alternative strategies or options were also provided as suggested by the Delphi consensus (Table 3).

CST and carers burden

Patients with dementia are usually dependent on family members and carers. They usually require assistance in their daily life routine. This includes mobility and transports. Carers are usually overwhelmed and sometimes burdened especially that they have other work and family obligations. Six out of ten patients who refused participating in this CST pilot group reported that coming to the group was extra work for their carer. Moreover, two patients dropped out early due to the same reason. In a study conducted in Brazil, the following barriers to CST were identified, extra work to the carer and transport distance from patients’ home. Strategies that were recommended by the authors were gaining the support of the carer, reducing the frequency to once weekly session and engaging the carers in an activity while they wait [20]. It was also noticed that there is limited awareness of the public and dementia carers in Egypt of the usefulness of the non-pharmacological interventions for dementia including CST [24]. We recommend increasing the public awareness of CST and engaging patients’ carers through psychoeducation and family support.

Duration and frequency of the sessions

The original CST manual recommended a 45-minute session twice weekly. Increased number of sessions per week may be considered as a barrier to regular attendance and may increase drop outs, especially if the patient should be accompanied by his carer and is travelling a long distance from home. In the staff acceptability survey, 53.3 % of staff members expected a high drop-out rate and 66.7 % of them agree that once weekly session is suitable for patients versus 33.3 % who recommend two sessions per week. However, 66.7 % of patients who attended the CST group recommend two sessions per week. The Delphi group argued that although twice weekly sessions may be associated with better patient outcomes, a once weekly session is more feasible for Egyptian population unless the group is conducted in a residential facility or geriatric home. A study looking into the effectiveness of once weekly CST concluded that it may not offer the necessary dose required to combat cognitive decline [34]. Most of the Staff members and patients preferred a session duration of 45 minutes to 1 hour. More than 1 hour was viewed by the Delphi as lengthy yet allowing breaks and patient assistance as needed. A session duration of an hour was viewed appropriate.

The convenience of the setting

Though CST is a simple intervention that doesn’t require special preparation or material and can be conducted in several settings including outpatient clinics, day care centres, geriatric social centres, residential care facilities and inpatient dementia wards, the majority of our staff believed that outpatient clinics and day care centres are the most convenient settings. The Delphi group consensus thought that inpatient dementia wards were less convenient as they usually included cases with severe dementia that may be associated with behavioural manifestations followed by residential facilities.

Educational levels and literacy

In Egypt there is a wide range of levels of education and social structures with a significant level of illiteracy which should be taken in consideration. Therefore, question of whether the CST group activities are suitable for patients with different educational levels and illiterate patients and whether adjustments were required was considered was raised. Most staff members and patients agreed that the activities could be tailored for different educational levels. Patients participating in this CST pilot group had number of formal educational years ranging from 2 to 11 with mean and SD of 5.036 ± 4.262. The following adaptations were recommended for illiterate patients, replacement of worksheets provided in the manual by Family tree/School/work/City worksheet in which the patient may use drawings to discuss his childhood and life events instead of writing, conventional maps were replaced by an illustrated map of Egypt with governments identified by their famous features. A recommendation was made by the authors of the CST study conducted in rural Nigeria to consider low levels of education, work and social backgrounds of patients, and uncorrected hearing and visual problems in adaptation [17].

Socioeconomic levels

Patients from different socioeconomic backgrounds may find difficulties in some activities that require description of their home, school environment, interests, hobbies and travel details. Adaptations included focusing on common interests like, describe your city and work environment which is particularly relevant in groups including patients with different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Egyptian culture considerations

The influence of cultural factors on the adaptation of CST was evident in the study done in Hong Kong where the authors identified 2 key cultural issues:

(i) less active opinion sharing in group discussions due to conservatism/cautiousness and

(ii) preference of practical activities with reward/ recognition over pure discussion due to pragmatism. The authors recommended a group of coping strategies that involved material reinforcement in the form of gifts and food, focus on group cohesiveness, and using rituals and actions rather than simple group discussions [19].

People in the Arab cultures have high regard and concern for the elderly. In describing the customs of the Egyptians, descriptive writings of modern times say the younger show great respect to them and believe that their prayers and vows are answered. Children particularly in villages are often instructed to kiss the hands of older people, young people are encouraged to listen to and learn from the elders. The wisdom of the old is seldom questioned. Elderly people usually live in extended families where they are cared for by their children and grandchildren and have influence over them [35].

Therefore, it was important to provide Egyptian patients with activities that were appealing, interesting, culturally appropriate and respectful. Accordingly, topics that were viewed religiously or culturally by them as inappropriate or childish were replaced with others. Activities like animal sounds were viewed as infantilizing by our patients and accordingly were replaced with other sounds. Word Associations were replaced with Egyptian famous proverbs, slogans or known couples. Art styles were replaced with culturally appropriate arts and crafts (pottery/Tanoura dancing/carpet art/ copper industry). Cards, domino, backgammon were suggested as games instead of bingo and chess. At the end of each session patients were invited to have a snack or lunch together to promote group unity.

Clinical Implications

Results obtained from this pilot study may indicate that CST offered benefit in cognitive functions of our patients as evidenced by the improvement of MOCA-B scores (P˂0.05), however we were not able to show any significant improvement in mood as measured by the GDS (P˃0.05). Studies with a larger sample are required to confirm these findings. The availability of a culturally adapted version of group CST manuals in Arabic language will allow the use of this evidence-based therapeutic intervention among Egyptian and other Arabic speaking patients suffering from dementia. Moreover, this will also enable a greater number of health care professionals caring for patients suffering from dementia to become familiar with the basics and application of group CST.

Limitations

Limitations of this work include the small sample size of staff and patients surveyed. Moreover, the group CST participants did not include women, patients from different socioeconomic levels, and patients suffering from moderate dementia. Accordingly, some barriers could not be identified. Moreover, the study did not perform interviews with the carers and did not measure other variables like activities of daily living and quality of life among patients.

Conclusion

The study concludes that group CST is acceptable among health care professionals working with dementia in Egypt. After cultural adaptation, it was applicable and acceptable to a sample of Egyptian patients suffering from mild dementia. Future research should focus on measuring the efficacy of group CST among Egyptian patients suffering from mild to moderate dementia compared to the available treatments for dementia in Egypt. We hope this tool will encourage other researchers to measure effectiveness in Egyptian culture and other clinicians to offer services provision.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Professor Aimee Spector and her team for permission of adaptation of the manuals.

Aston Medical School, Aston University, U.K. for purchasing copyrights of the manuals.

Dr. Gemma Ridel, Principal Psychologist Suffolk & Norfolk NHS, U.K. for conducting the training.

Ms. Shimaa Mady, Old Age Psychologist, Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University for conducting the group sessions.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Spector A, Orrell M, Davies S, Woods RT (1998) Reality orientation for dementia: a review of the evidence of effectiveness, Gerontologist 40(2):206-212. The Cochrane Library Oxford: Update Software.

- Spector A, Davies S, Woods B, Orrell M (2000) Reality orientation for dementia: a systematic review of the evidence of effectiveness from randomized controlled trials. Gerontologist 40(2): 206-212.

- Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B, Royan L, Davies S, et al. (2003) Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatr 183: 248-254.

- Knapp M, Thorgrimsen L, Patel A, Spector A, Hallam A, et al. (2006) Cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia: Cost-effectiveness analysis. Br J Psychiatr 188: 574-580.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence London (2018) Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers (NG97).

- Patterson C (2018) World Alzheimer’s Report-The state of art of dementia research: New frontiers. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Wood B, Orrell M (2006) An evidence-based group programme to offer cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) to people with dementia. The Journal for Dementia Care. London, UK: Hawker Publications.

- Aguirre E, Spector A, Hoe J, Streater A, Woods B, et al. (2011) Development of an evidence-based extended programme of maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for people with dementia. Non-Pharmacological Therapies in Dementia Journal 1(3): 197-216.

- Orrell M, Aguirre E, Spector A, Hoare Z, Woods RT, et al. (2014) Maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: Single-blind, multicentre, pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatr 204(6): 454-461.

- Yates L, Leung P, Orgeta V, Spector A, Orrell M (2014) The development of individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) for dementia. Clin Interv Aging 10:95-104.

- Orrell M, Yates L, Leung P, Kang S, Hoare Z, et al. (2017) The impact of individual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (iCST) on cognition, quality of life, caregiver health, and family relationships in dementia: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 14(3): e1002269.

- Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, Orrell M (2012) Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005562.

- Lobbia A, Carbone E, Faggian S, Gardini S, Piras F, et al. (2019) The efficacy of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for people with mild-to-moderate dementia: A review. European Psychologist 24: 257-277.

- Gibbor L, Yates L, Volkmer A, Spector A (2020) Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for dementia: a systematic review of qualitative research. Aging and Mental Health 25(6): 980-990.

- Yamanaka K, Kawano Y, Noguchi D, Nakaaki S, Watanabe N, et al. (2013) Effects of cognitive stimulation therapy Japanese version (CST-J) for people with dementia: a single-blind, controlled clinical trial. Aging Ment Health 17(5): 579-586.

- Mkenda S, Olakehinde O, Mbowe G, Siwoku A, Kisoli A, et al. (2018) Cognitive stimulation therapy as a low-resource intervention for dementia in sub-Saharan Africa (CST-SSA): Adaptation for rural Tanzania and Nigeria. Dementia (London) 17(4): 515-530.

- Olakehinde O, Adebiyi A, Siwoku A, Mkenda S, Paddick, et al. (2020) Managing dementia in rural Nigeria: feasibility of cognitive stimulation therapy and exploration of clinical improvements. Aging and Mental Health 23(10): 1377-1381.

- Raghuraman S, Lakshminarayanan M, Vaitheswaran S, Rangaswamy T (2017) Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for Dementia: Pilot Studies of Acceptability and Feasibility of Cultural Adaptation for India. Am J of Geriatr Psychiatry 25(9): 1029-1032.

- Wong GHY, Yek OPL, Zhang AY, Lum TYS, Spector A (2018) Cultural adaptation of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for Chinese people with dementia: multicentre pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33(6): 841-848.

- Bertrand E, Naylor R, Laks J, Marinho V, Spector A, et al. (2019) Cognitive stimulation therapy for Brazilian people with dementia: Examination of implementation’ issues and cultural adaptation. Aging and Mental Health 23(10): 1400-1404.

- Dugmore O, Orrell M, Spector A (2015) Qualitative studies of psychosocial interventions for dementia: A systematic review. Aging Ment Health 19(11): 955-967.

- Stoner C, Lakshminarayanan M, Durgante H, Spector A (2019) Psychosocial interventions for dementia in low and middle-income countries (LMICs): a systematic review of effectiveness and implementation readiness. Aging Ment Health 25(3): 408-419.

- Egypt demographics (2020).

- Elshahidi M, Elhadidi M, Sharaqi A, Mostafa A, Elzhery M (2017) Prevalence of dementia in Egypt: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 13: 715-720.

- Odejimi O, Tadros G, Sabry N (2020) Prevalence of Mental Disorders, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia Among Older Adults in Egypt: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR Res Protoc 9(7): e146347.

- Aguirre E, Spector A, Streater A, Hoe J, Woods B, et al. (2012) Making a difference 2: Volume two: An evidence-based group programme to offer maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) to people with dementia. London, UK: Hawker Publications.

- Aguirre E, Spector A, Orrell M (2014) Guidelines for adapting cognitive stimulation therapy to other cultures. Clin Interv Aging 9: 1003-1007.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (2013). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P (1975) Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3): 189-198.

- Julayanont P, Tangwongchai S, Hemrungrojn S, Tunvirachaisakul C, Phanthumchinda, et al. (2015) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic: A Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment in Illiterate and Low-Educated Elderly Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63(12): 2550-2554.

- Saleh AA, Alkholy RSAEHA, Khalaf OO, Sabry N, Amer H, et al. (2019) Validation of Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic in a sample of elderly Egyptians with neurocognitive disorders. Aging and Mental Health 23(5): 551-557.

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA (1986) Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In T.L. Brink (Ed.), Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention (pp. 165-173). NY: The Haworth Press.

- Dickinson C, Gibson G, Gotts Z, Stobbart L, Robinson L (2017) Cognitive stimulation therapy in dementia care: Exploring the views and experiences of service providers on the barriers and facilitators to implementation in practice using Normalization Process Theory. Int Psychogeriatr 29(11): 1869-1878.

- Cove J, Jacobi N, Donovan H, Orrell M, Stott J, et al. (2014) Effectiveness of weekly cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia and the additional impact of enhancing cognitive stimulation therapy with a carer training program. Clin Interv Aging 9: 2143-2150.

- Peters I (1986) The attitude towards the elderly as reflected in Egyptian and Lebanese proverbs. The Muslim world 76(2): 80-85.