Factors Associated with Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Diabetic Patients in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos

Ogbonna Adaobi Nneamaka1*, Ayonote Uzoramaka Angela1 and Akujuobi Obianuju Mirian2

1Department of Family Medicine, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

2Department of Counselling Psychology, Yorkville University, New Brunswick, Canada

Submission: July 14, 2022; Published: August 16, 2022

*Corresponding author: Ogbonna Adaobi Nneamaka, Department of Family Medicine, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-Araba, Lagos, Nigeria

How to cite this article: Ogbonna A N, Ayonote U A, Akujuobi O M. Factors Associated with Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Diabetic Patients in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2022; 6(5): 555699. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2022.06.555699

Abstract

Background

Cognitive Impairment (CI) complicates Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and increases its burden to the patients, their caregivers and the society at large. Preventing the development and progression of cognitive impairment is a key strategy in reducing this burden. This study sought to determine the prevalence of Cognitive impairment and identify its risk factors among diabetes patients attending endocrinology unit of Lagos University teaching hospital, Lagos.

Method

This was a hospital-based, observational, cross-sectional study involving 126 diabetic patients randomly selected. Using an adapted, semi-structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire, data including sociodemographic characteristics, income, cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle features were collected. Cognition was tested using the 6-item cognitive impairment test, and scores 1-7 was considered normal, 8-10 was mild CI, while >10 was severe. The proportion of participants with mild and severe impairment was calculated to obtain the prevalence of cognitive impairment. Factors associated with Cognitive impairment were investigated using Chi-square test and predictors were identified after a multivariate regression analysis. Significant level was set at p<0.05.

Results

Of the 126 participants, most were female (64.3%), aged between 60-64 years (53.9%), married (70.6%) with tertiary education (43.7%). The prevalence of cognitive impairment was 32.6%, made up of 5.6% and 27.0% of mild and severe cognitive impairment respectively. Age (χ29.77; p-0.021), income (χ2=9.04; p-0.003), hypertension (χ2=6.19, p-0.045) dyslipidemia (χ2 =6.72, p-0.035), physical activity (χ2=4.94, p-0.026), and previous use of tobacco (χ2=5.48, p-0.019) were significantly associated with cognitive impairment. Only age (aOR-23.44; p-0.016) and physical activitiy (aOR-0.23; p-0.008) were identified as significant independent risk factors among diabetic patients.

Conclusion

Cognitive impairment is common among elderly T2DM patients, it is associated with income, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, physical activity and tobacco use. Screening for CI, and effective management of DM, hypertension and dyslipidaemia as well as encouraging physical activity will hinder the progression of cognitive impairment to dementia among T2DM patients in this locality.

Keywords: CST; Egypt; Cognitive Stimulation; Cognitive Disorders; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; Multidisciplinary Cognitive Rehabilitation Programme; Dementia; Elderly people; Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5; Anti-choline Esterase Inhibitors

Introduction

Cognitive Impairment is one of the Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) associated with aging [1]. It is characterized by global and irreversible cognitive decline [2]. Cognitive functioning is classically categorized into 5 domains namely learning and memory, language, visuo-spatial, executive and psychomotor domains [3]. There are cerebral localizations linked with these domains. In Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), one domain is impaired without undermining daily function and independence whereas in dementia more than one domain is impaired and associated with significant impairment of daily function and independence of the affected individual [2-3].

Mild Cognitive Impairment is viewed as a precursor to dementia in up to one third of the cases of dementia [2-3] reported a progression rate of 7.1% per year to dementia among elderlies diagnosed with MCI as against a rate of 0.2% per year among cognitively normal persons. Furthermore, reported an annual conversion rate of 5% to 10% among persons with MCI progressing to Dementia [4]. Mild cognitive impairment occupies the intermediate stage in the continuum between normal cognitive functioning and dementia, it is hence considered the leading edge in preventive strategies for Dementia [5].

Dementia is a major cause of disability and dependency in older people [2-6] The strain imposed by dementia and its precursor- MCI on the individual and caregivers is huge with loss of income, psychosocial stress, significant social and economic implications in terms of direct medical and social care costs and the costs of informal care [5-7]. The total global societal cost of dementia was estimated to be US$818 billion in 2015 which is equivalent to 1.1% of Global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [7]. This massive impact on individuals and societies, makes preventing the onset of cognitive impairment and its progression to dementia an imperative task which will lead to enormous public health and societal benefits [8].

The prevalence of dementia increases with age and is therefore expected to rise with the aging of populations worldwide [9]. A systematic review conducted revealed that the prevalence of cognitive impairment in people aged 60 and older varied between 4.4% and 17.7% [4]. A study done by [10], in 2010 estimated 35.6million people worldwide living with dementia. The impact of population ageing in sub-Saharan Africa will progressively augment the burden of non-communicable and degenerative diseases in the region [2]. In 2010, 57.7% of all people with dementia lived in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC). This is expected to rise to 63.4% in 2030 and 70.5% in 2050.10 The health and social burden of cognitive impairment and dementia will therefore rise dramatically in these regions [2]. Few studies to determine the prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia have been conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [2,11-12]. The prevalence of cognitive impairment ranged from 6.3% in Nigeria to 25% in the Central African Republic found the prevalence of cognitive impairment to be 49.1% in a study done in South-South Nigeria [12]. According to the age-adjusted prevalence estimates were 18.4% and 2.9% for mild cognitive impairment and dementia respectively [11].

There is strong evidence that Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia [13]. Studies have reported associations of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) with an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia, including Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and vascular dementia [14]. A metaanalysis of longitudinal studies showed that diabetes was a risk factor for MCI and incident dementia [15]. A hospital-based study carried out in South-East Nigeria showed that the prevalence of cognitive impairment among older adults with T2DM was 17.8% [16].

There are also suggestions to support the link between other modifiable risk factors and cognitive decline [17]. These modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, obesity, smoking, unhealthy diet, dyslipidaemia and hypertension [17-18]. Risk factors for cognitive impairment in American and European countries have been well investigated, however little research has been carried out in West Africa where environmental, socioeconomic, and modifiable risk factors may differ [19]. Studies investigating cognitive impairment in the African subregion is essential because majority of older adults in the world reside in developing countries and projections suggest that by 2040, 71% of the people with dementia in the world will reside in developing countries [20]. In Nigeria, as well as in many other African countries, cognitive impairment is often seen as a sign of aging and little is done to explore the potential treatment of such impairment [18]. This leads to a missed opportunity for early intervention. Furthermore, in Africa, caregiving generally takes place within the family/household setting, leading to late recognition of symptoms, late presentation, poor prognosis and rapid progression to dementia which is associated with caregiver distress [18].

Cognitive Impairment is principally assessed by a medical history and a mental state examination [3]. General neurological examination may be carried out; this mainly gives insight to the aetiology of the cognitive disorder [3]. For medical history, thorough history from both the patients and caregiver who knows patient well is important. Inventories of daily activities like the 10-item functional activities questionnaire have been developed to aid the investigation of patients’ strength and weaknesses in daily living [3,21-22]. Tools for mental state examination also abound. These include the Mini Mental state examination (MMSE), the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG), Clock Drawing Test (CDT), Mini-Cog, Six item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-item CIT), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) and the Short Test of Mental Status (STMS) amongst others [23-28]. These instrument are however, associated with varying degrees of diagnostic accuracy and limitations that hinder their applicability in different settings. These limitations include educational and cultural bias, duration of administration, and scope of impairment (the domains) tested by the instrument. The 6-item CIT is a brief and easily administered test with reported sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive value of 90%, 100%, 100% and 83% respectively. It has been widely validated in Nigeria especially among T2DM patients demonstrating high diagnostic accuracy and discriminative properties which showed its impact on disease and sex on cognitive functioning of study participants [29-31].

Currently, there is no known cure for dementia. Primary prevention through identification of modifiable risk factors as well as interventions that aim at preventing the progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia should be encouraged [32]. Lifestyle modification, early screening and treatment of diabetes may reduce the rate of cognitive decline [33]. Routine cognitive screening in those with diabetes is also warranted by the preponderance of evidence supporting a significant link between diabetes and cognitive decline [33]. It is expected that reduction of these risk factors will reduce the risk of cognitive decline [17]. Hence, this study was conceptualized to determine the prevalence of cognitive impairment and its risk factors among diabetic elderly patients accessing care at the endocrinology clinic of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) using the six-item cognitive impairment test. It is hoped that findings from the study will be instrumental to the design of evidence-based preventive strategies for the development of mild cognitive impairment and its progression to dementia among the elderly especially those with T2DM in this locality.

Methodology

Study Area

The study was conducted at the Endocrinology clinic of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH). Lagos is a metropolitan state located in South-West Nigeria with a population of about 21 million which makes it the largest city in Africa [34]. It is multi-ethnic and urban though the Yorubas constitute the major ethnic group [34]. The Lagos University Teaching Hospital was established in 1962 and has since been involved in the training of both undergraduate and postgraduate medical, dental and paramedical students. It has 811 bed spaces for inpatient care and several outpatient clinics. It provides care in the major specialties of medicine to patients within and around Lagos as well as all over Nigeria. The Endocrinology clinic of the Department of Medicine, LUTH offers specialist care to adult diabetic patients. It offers follow up care to diabetic patients on Tuesdays while newly diagnosed diabetic patients are seen on Mondays. Individuals who have been diagnosed with DM at various health centers and within LUTH are referred to this clinic for further specialist care.

Study Design

This study was a hospital-based, descriptive cross-sectional study which was part of a bigger comparative study.

Study Population

The study population consisted of elderly diabetic patients aged 60 years and above attending the Endocrinology clinic of LUTH within the period of study. Inclusion criteria include elderly diabetic patients aged 60 years and above who had been diagnosed with T2DM for a minimum of 6 months. Exclusion criteria include acutely-ill patients [35], any elderly with history suggestive of secondary cause of cognitive impairment (recent head injury, thyroid disease, HIV, ongoing depression, psychoactive substance use and stroke within the past six months), history suggestive of neuropsychiatric illness, delirium and hearing impairment [36-37] and elderly with a fasting blood glucose of ≥126mg/dl who are not aware of their diabetic status.

Sample Size Determination

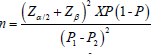

This study was part of a bigger research that compares the cognitive function of diabetic and non-diabetic patient, hence sample size was calculated using the formula for comparing two proportions shown below [38].

where n is the minimum sample size in each group,  is

the standard normal deviate at 95% confidence interval which

corresponds to 1.96, Zβ represents the standard normal deviate

at a power of 80% given as 0.84 and P1 is the proportion of elderly

diabetic patients estimated to have cognitive impairment reported

as 51.6% in a study by [16] in Ebonyi state, south-east Nigeria.

P2 is the proportion of elderly non-diabetic patients estimated to

have cognitive impairment which was 33.3% in a study conducted

in 2019 in Cameroun [39]. P1-P2 is the difference in proportion

of events in two groups and P is the pooled prevalence given by

(P1+P2)/2. Substitution yielded a minimum sample size of 114

participants per group, which was adjusted for non-response

using a non-response rate of 10%. Adjusted sample size was 126

per group. Hence, 126 participants in the diabetic arm of the study

were reported in this article.

is

the standard normal deviate at 95% confidence interval which

corresponds to 1.96, Zβ represents the standard normal deviate

at a power of 80% given as 0.84 and P1 is the proportion of elderly

diabetic patients estimated to have cognitive impairment reported

as 51.6% in a study by [16] in Ebonyi state, south-east Nigeria.

P2 is the proportion of elderly non-diabetic patients estimated to

have cognitive impairment which was 33.3% in a study conducted

in 2019 in Cameroun [39]. P1-P2 is the difference in proportion

of events in two groups and P is the pooled prevalence given by

(P1+P2)/2. Substitution yielded a minimum sample size of 114

participants per group, which was adjusted for non-response

using a non-response rate of 10%. Adjusted sample size was 126

per group. Hence, 126 participants in the diabetic arm of the study

were reported in this article.

Sampling Technique

The diabetic participants were recruited from Endocrinology clinic over a period of three months (12 weeks) between October and December 2020. Ten to twelve elderly diabetic patients aged 60 years and above were selected using a systematic random selection technique. From the attendance record of the Health Information Management System (HIMS) of the hospital, there was clinical attendance of about 120 diabetic patients on diabetic follow up clinic days. Out of the 120 patients, about 25 on the average were aged 60 years and above, hence using a sampling interval of 2, 10-12 diabetic patients were recruited every clinic day to participate in the study.

Study Instrument

A pre-tested, semi-structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. The study instrument is made up of five sections namely: Section A which captures socio-demographic information of participants. This includes age, gender, level of education, occupation, average monthly income, marital status, religion, and ethnicity. Section B explored the medical, medication and family history as reported by the participants. Section C investigated lifestyle characteristics which included information on physical and social activity, alcohol, and tobacco use. Section D examined cognitive function of the participants using the 6-item cognitive impairment test. The 6-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) is a short and simple test of cognition used to assess cognitive impairment in the elderly within two-three minutes. It consist of six questions designed to test concentration and memory [29-31]. It is scored from 0-28. Scores of 0-7 indicates normal cognition; 8-9 suggests mild cognitive impairment and 10-28 suggests severe cognitive impairment [29-31]. Section E recorded results from clinical and laboratory measurements which include weight, height, Body Mass Index (BMI), blood pressure, fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels. The study instrument was pretested among 15 diabetic patients who were aged 60 years and above attending the Endocrinology clinic of Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH). Pretesting was done to check the applicability of the questionnaire in this setting and confirm the clarity of items in the questionnaire. Parts of the study tool were modified based on findings from the pretesting to improve its clarity.

Study Procedure

Data was collected with the help of two research assistant who were medical doctors (MBBS graduates) who just completed their one-year mandatory internship program. They were selected based on their background medical knowledge, their venepuncture skills and their proficiency in English and Yoruba language. The training was carried out by the principal investigator, it lasted a total of 6 hours (2 days of 3-hour sessions). They were trained on the objectives, benefits, selection, and procedure of the study, assuring confidentiality, explaining the data collection process, taking informed consent, ensuring a comfortable and private environment, and administering the questionnaire. They were also trained on brief counselling techniques, and how to give the participants feedback on their test results. There was a role play between assistants and principal investigator to conclude the training.

On each research day, the first participant was determined by simple random sampling (balloting) between the first and second elderly diabetic patients attending the clinic. Using a sampling interval of 2, systematic sampling was deployed to recruit other participants for the study every clinic day. Patients who were selected for the study, had their folders tagged at the health record’s registration desk and sent to the designated consulting rooms where they were informed about the study and informed consent sought. They were allowed to ask questions for clarification. Patient who gave consent were thereafter recruited for the study. When included in the study, an interviewerbased questionnaire was administered, the blood pressure, anthropometric measurements and fasting blood sugar were done. Participants who had not fasted for at least 8 hours were given an appointment for the test. Samples for HbA1c were also taken in the study participants.

Data analysis and management

Each completed questionnaire was cross-checked for completeness and correctness by the principal researcher after every interview. Data was entered into Microsoft EXCEL software where cleaning was done and later exported to Statistical package for scientific solutions (SPSS) version 26 which was used for data analysis. Univariate analysis was done to uncover descriptive statistics including socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, educational level, ethnicity etc), social and medical history, income, clinical features, anthropometric measurement, and risk factors in participants. Categorical variables were summarized in frequencies and proportions, while mean and standard deviation or median and range were used as appropriate in presenting continuous data. The primary outcome variables were level of cognition, diabetes mellitus and HbA1c values. The score obtained by each patient in the 6-CIT test was graded as follows; 6-CIT scores of 1-7 was graded as normal cognition; 8-9 was categorized as mild cognitive impairment and while 6-CIT score ≥ 10 was classified as significant cognitive impairment. Bivariate analyses were carried out to investigate the association between variables; with Chi square test we explored the association between cognitive function (dependent variable) and independent variables like sociodemographic characteristics like age, marital status, income; cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, obesity; lifestyle features e.g physical and social activities. Bivariate logistic regression analysis investigated the strength of association between risk factors and cognitive impairment. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine significant predictors of cognitive impairment. The level of statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Health Research and Ethical Committee of LUTH. Written signed informed consent was obtained from each participant at the point of recruitment. Participants were assured of confidentiality on all information obtained from them and the questionnaires were safely and securely stored for research purpose only. The completed questionnaires were serially coded with numbers without any links to identifying the participants.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and anthropometric measurement of study participants

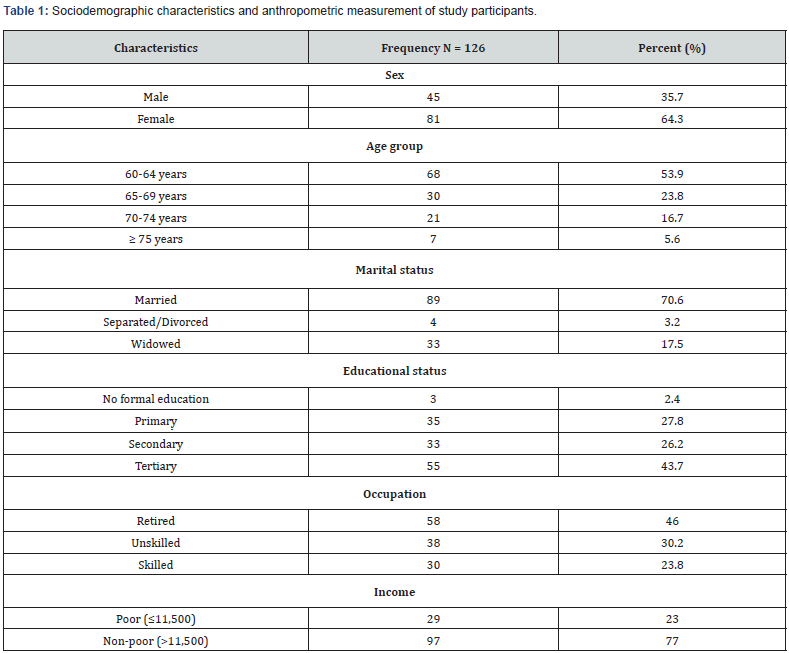

The study involved 126 elderly diabetic patients who had been diagnosed for more than 6 months prior to the study. Of the 126, 45 (35.7%) were male, while 81 (64.3%) were females (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 65.3 years with a standard deviation of 5.9 years. The modal age group was 60 to 64 years (Table 1). Majority of the participants were married (70.6%), non-poor (77.0%) with tertiary education (43.7%) and retired (46.0%). (Table 1) further shows that 45.2% of them were overweight and the mean body mass index of participants in the study was 27.21 ± 5.3kg/m2.

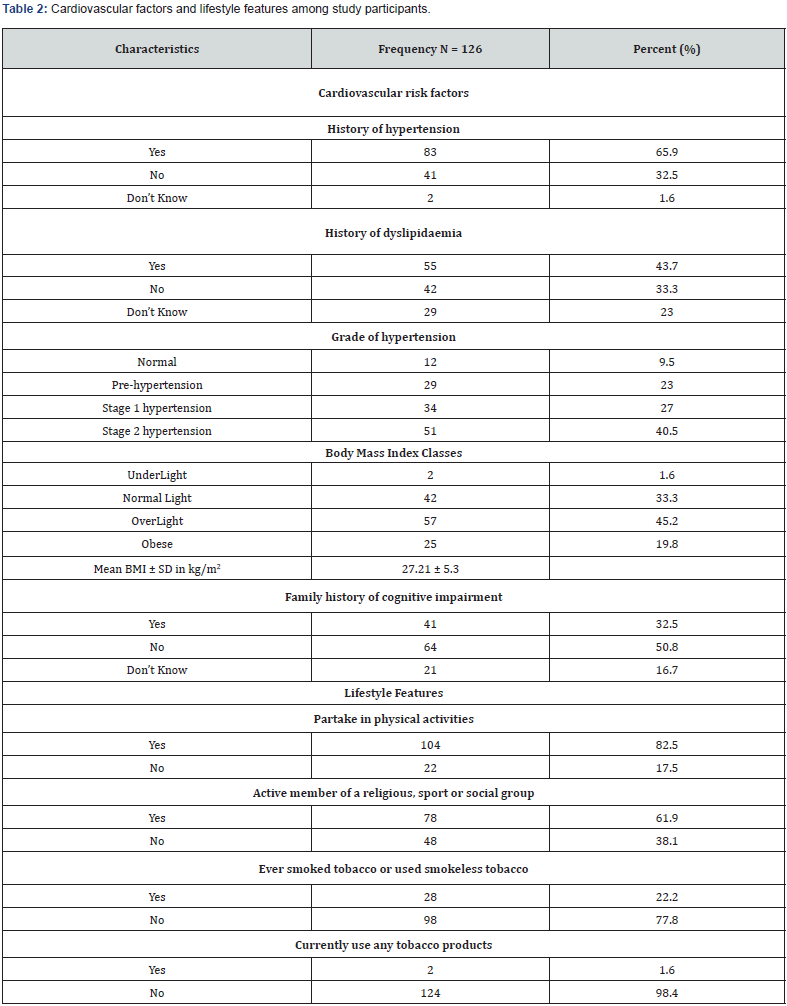

Comorbid conditions, Lifestyle and Blood pressure readings among study participants

About two-third of participants were known hypertensive patients (65.9%) and 43.7% had a history of dyslipidaemia while about a third (32.5%) had a positive family history of cognitive impairment (Table 2). One hundred and four participants (82.5%) partake in physical activities outside their daily self-care routine while 78 participants (61.9%) were active member of a religious, sports and social group. Though 22.2% of participants had used tobacco or smokeless tobacco at some point in life, only 2 (1.6%) were currently using tobacco product at the time of the study (Table 2).

Cognitive function among study participants

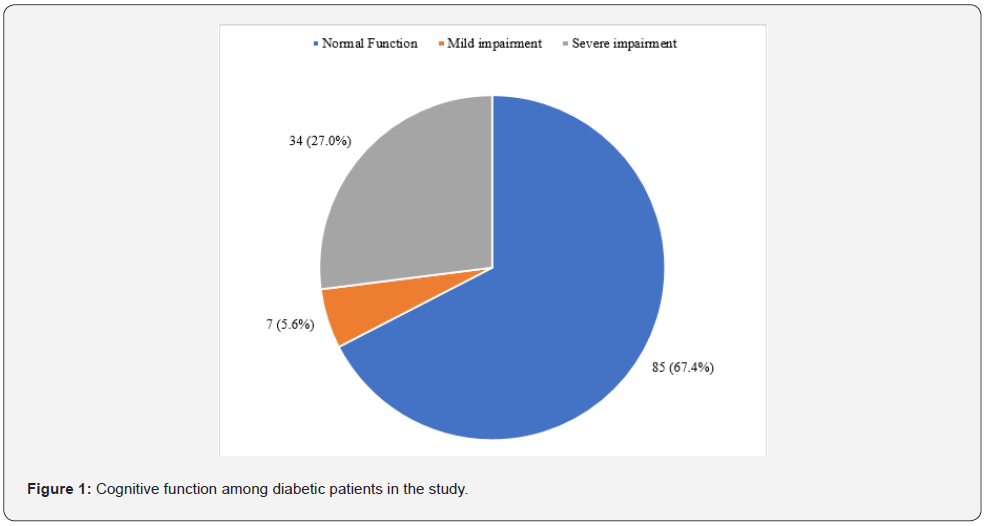

The cognitive function scores obtained using the 6-item CIT range between 0 and 23 points with a median score of 4 points. (Figure 1) shows that 67.4%, 5.6% and 27.0% of study participants had normal cognitive function, mild and severe cognitive impairment respectively. Hence, a total of 48 participants (32.6%) had varying degree of cognitive impairment among diabetic patients in the study.

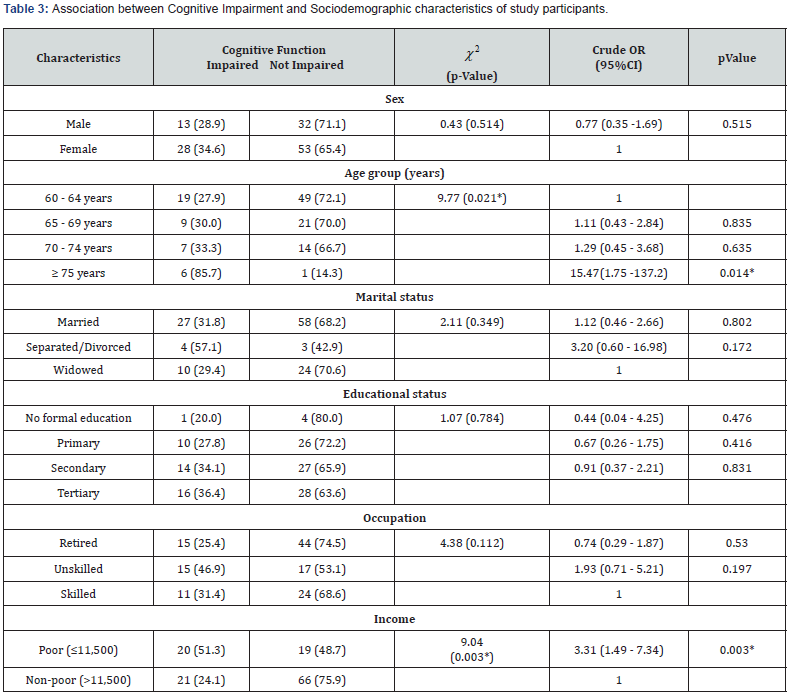

Association between Cognitive Impairment and sociodemographic characteristics in Diabetic Participants

There was a statistically significant association between age ( χ2 = 9.77; p- 0.021) and income (χ2 = 9.04; p - 0.003) and cognitive impairment (Table 3). While the odd of cognitive impairment was 15 times higher among diabetic patients 75 years and above (OR = 15.47; p -0.014), participants categorized as poor were 3 times more likely to have cognitive impairment (OR = 3.31; p - 0.003). Other socio-demographic factors such as gender (χ2 = 0.43; p - 0.514), marital status (χ2 = 2.11; p - 0.349) occupation (χ2 = 4.38; p - 0.112) and educational level (χ2 = 1.07; p - 0.784) were not significantly associated with cognitive impairment.

**Fischer exact test, χ2 = Chi square, * Statistically significant

Association Between Cognitive Impairment and cardiovascular risk, lifestyle Characteristics among Diabetic Participants

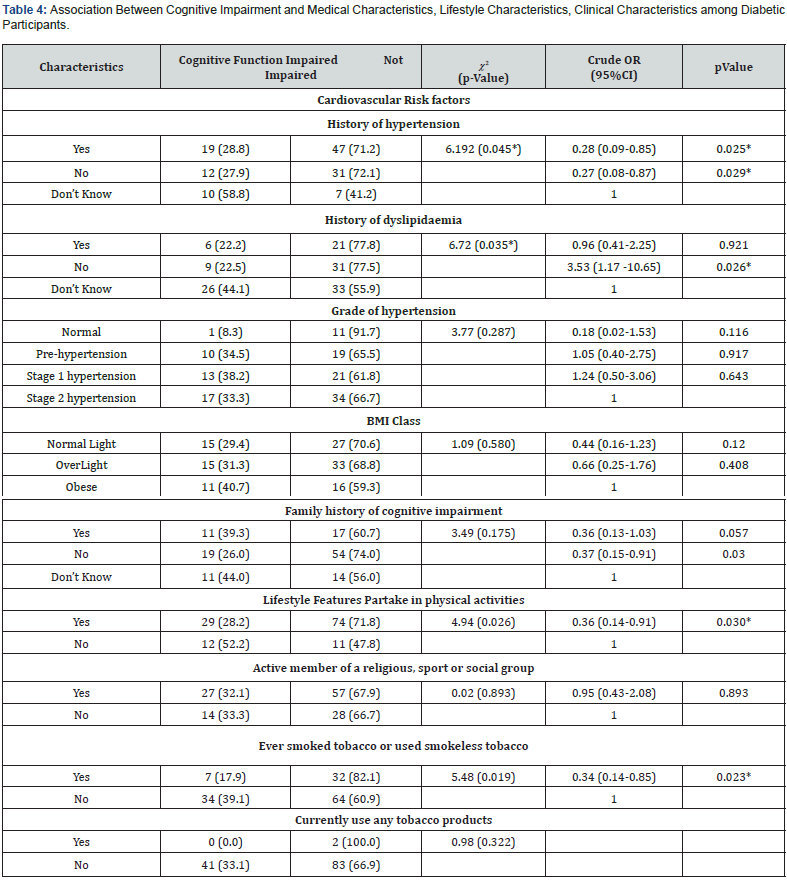

(Table 4) shows that among diabetic participants, there was a statistically significant association between cognitive impairment and history of hypertension (χ2 = 6.19, p - 0.045) as well as history of dyslipidemia (χ2 = 6.72, p - 0.035) but the severity of hypertension (χ2 = 3.77, p - 0.287) and body mass index (χ2 = 1.09; p - 0.580) were not significantly associated with cognitive impairment (Table 4). Furthermore, (Table 4) shows that there was a statistically significant association between physical activity (χ2 = 4.94, p - 0.026), previous use of tobacco or smokeless tobacco (χ2 = 5.48, p - 0.019) and cognitive impairment among diabetic patients. However, family history of cognitive impairment (χ2 = 3.49, p - 0.175), social activity (χ2 = 0.02, p - 0.893), and current use of tobacco products (χ2 = 0.98, p - 0.322) were not significantly associated with the occurrence of cognitive impairment among diabetic patients.

Predictors of cognitive impairment among study participants

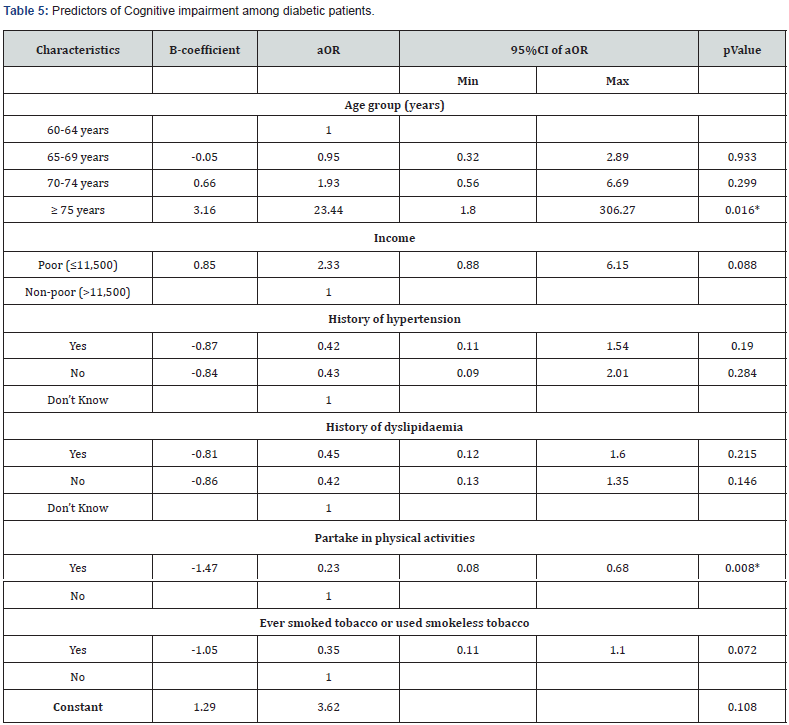

(Table 5) shows that age of participants (aOR - 23.44; p - 0.016) and physical activity (aOR -0.23; p - 0.008) remained associated with cognitive function after the multivariate binary logistic regression was applied. Age 75 years and older was found to be an independent predictor of cognitive impairment in the diabetic elderly participants. Respondents aged 75 years or older are 23 times more likely to have impaired cognitive function compared to those that were less than 75 years. Physical activity was also an independent predictor of cognitive impairment in diabetic elderly participants (P= 0.002) as those who engaged in physical activities outside their daily self-care routine had a reduced odd of having cognitive impairment compared to those who did not (Table 5).

χ2 = Chi square; *Statistically Significant; Variable with shaded row was not included in bivariate logistic regression because there was no participant in the category of the variable.

Discussion

Prevalence. Cognitive impairment was defined by the 6-item CIT score > 7, this was found in 32.6% of the diabetic patients studied. This is similar to the 27% prevalence of impaired cognitive function among T2DM patients reported by in Kwara state, north-central Nigeria [40] but slightly lower than 40% prevalence reported mong diabetic patients in the South-east Nigeria [16]. Studies in other parts of Africa and different part of the globe have reported varying prevalence among elderly T2DM patients. [19] in central African republic and in Ethiopia [41] found 25% and 53.3% prevalence, respectively, while 23% was reported in Argentina [42]. Even lower prevalence of 9.6% and 9.9% were found in India by [43] and [44] in China respectively. The varying prevalence could be explained by the different settings in which the studies were conducted. While some studies like those in Kwara [40] Enugu [16] and the index study were hospital-based studies, the Central African Republic [19] India [43] and China [44] studies were population-based studies. As suggested by [16], the variation in prevalence could also be accounted for by the different tools used for the assessment of cognitive impairment and sociodemographic characteristics of the population studied [16,40-44]. It is however clear from the above that cognitive impairment is common among elderly diabetics globally.

Age

This study found age and physical activities beyond daily self-care routine were independent predictors of cognitive impairment among T2DM in this locality. The index study clearly demonstrated increasing prevalence of cognitive impairment as age increases. Several studies, both locally and internationally, have established a very strong association between age and cognitive decline [15,37,43,45]. Age, family history of cognitive impairment and genetic susceptibility genes eg Apolipoprotein E allele have been identified as the strongest risk factors for cognitive impairment especially in diabetic patients [3]. The process of aging leads to the formation and deposition of insoluble protein metabolic products in the brain which precedes neuronal death by apoptosis. This results in cerebral atrophy and ultimately cognitive impairment [16,46]. Age is also associated with other factors known to increase the risk of cognitive impairment like hypertension (leading cause of vascular dementia), dyslipidaemia, and stroke [3].

Physical activity

This study identified physical activity as an independent predictor/risk factor for cognitive impairment in diabetic patients. More than half of the participants who did not partake in physical activities outside their daily self-care routine had cognitive impairment while only about a quarter of those who were physically active had cognitive impairment. This implies that there is increased risk of cognitive impairment in diabetic elderly individuals with low physical activity. This corresponds to findings, where there was a reduction in the occurrence of MCI among physically active T2DM patients [47]. Another longitudinal study carried out in China found that daily exercise not less than 30 minutes a day was an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment in elderly T2DM patient [44]. This finding also corroborated conclusions from systematic reviews and randomized control trials, that physical activity as little as walking, reduces the risk of cognitive impairment [3]. Scientific evidence in favour of physical activity is considered very strong [2]. However, the optimal mix of type, intensity and duration of physical exercise needed is still very difficult to prescribe [2].

Income

Though, income, hypertension and dyslipidaemia may not be considered significant independent predictors of cognitive impairment in this study, they showed significant association at the bivariate analysis stage. Income was related to cognitive impairment in the diabetic participants. Among the participants living below the poverty line of N11,500, more than half of them had cognitive impairment while about a quarter of those with income above N11,500 had cognitive impairment. This implies that diabetic elderly people with low income have a higher chance of developing cognitive impairment than those whose income is above the poverty line. Similarly, showed that monthly income less than 2000 yuan was significantly associated with cognitive impairment in the elderly [48]. A study however, found no association between low income and cognitive impairment among diabetic participants [49].

Hypertension

Participants who knew their hypertensive status were less likely to develop cognitive impairment when compared to their counterparts in the study who do not know their hypertensive status. An Iranian study by similar, to our finding demonstrated an association between hypertension and cognitive impairment [50]. Participants who knew their hypertensive status are more likely to take medication for blood pressure control and ameliorate the effect of hypertension in the development of cognitive impairment. Those without hypertension are not exposed to its mechanism of cognitive impairment. However, patients who do not know their status were unknowingly exposed to this effect with its attendant risk of cognitive decline. It is also worthy to note that, ignorance of their hypertensive status could be an indication of cognitive impairment.

Dyslipidaemia

As regards dyslipidemia, this study revealed a statistically significant association between dyslipidemia and cognitive impairment. Amongst the diabetic participants, 44.1% of those who did not know if they had dyslipidemia had cognitive impairment, 22.5% of those without history of dyslipidemia had cognitive impairment, while 22.2% of those who had dyslipidemia had cognitive impairment. This means that there is a higher risk of cognitive impairment amongst those who did not know if they had dyslipidemia. Similar finding was revealed in a study by Sun et al. [51] which showed that dyslipidemia was significantly associated with cognitive impairment in diabetic patients [51]. Conversely, a study did not find any association between dyslipidemia and cognitive function in diabetic participants [52]. It is important to know, however, that the Yarube study was conducted among a relatively younger population than those in this study (< 60years). Another study by Yusuf et al. [37] also revealed that dyslipidemia was not significantly associated with dementia [37]. Dyslipidaemia was assessed by laboratory method by Yusuf et al. [37] while this study only relied on history of dyslipidemia.

Smoking

As regards smoking, this study revealed that there was a significant relationship between history of smoking and cognitive impairment in T2DM patients and history of smoking even seem to be protective. Though current smoking status was not related significantly to cognitive impairment, it is worthy to note that none of the participants who currently smoked or used smokeless tobacco had cognitive impairment as opposed to a third of participants who did not smoke and found to have cognitive impairment. Similarly, some studies have found that current smokers have lower risk of cognitive impairment compared to persons who never smoked [53-54] In consonance with these findings, an Ethiopian study by [41] found no significant association between smoking and cognitive impairment. Another study by [44]. revealed that smoking was not an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment in older people with DM.

Gender

As regards to gender, even though the prevalence of cognitive impairment was higher in female diabetics (34.6%) than in males (28.9%), this observed difference could not substantiate a significant association between gender and cognitive impairment in the diabetic elderly participating in this study. This finding contrast results from [31,37] [52] and Gwarzo from northern Nigeria and [12-16] from southern Nigeria. These studies reported that females were more likely to develop cognitive impairment. These finding was hinged on the low educational attainment of women in the northern region of Nigeria. A systematic review by [55] also concluded that years of schooling measured by grade level attained, lowers the risk of cognitive impairment [3,55] Another factor thought to predispose elderly women to cognitive impairment is the lost protection of oestrogen in the menopausal stage which predispose them to hypertension and in turn to cognitive impairment [16].

Marital Status

There was also no significant association between marital status and cognitive impairment in diabetic elderly participants in this study. Similarly, studies by [52,6,56] despite differences in their study designs, all concluded there is no significant association between marital status and cognitive impairment in the diabetic participants [49,52,56]. However, findings by Yusuf’s study revealed a significant association between dementia in the diabetic participants and absence of a spouse [37]. Results from systematic review suggests social contacts are associated with better cognitive function and reduce the risk for cognitive impairment, howbeit the strength of evidence is said to be unclear [3].

Occupational status

Occupational status of the diabetic participants was not statistically related to cognitive function. Similar findings were seen in a population-based Malaysian study by [57] which showed that there was no statistically significant association between occupation and cognitive impairment in diabetic participants. Conversely, a study South-East Nigeria, revealed a statistically significant association between unskilled occupation and cognitive impairment [16].

Limitation

The study is not without its limitation. First, it is a hospitalbased study and may not be a complete reflection of the prevalence of cognitive impairment in this locality. Secondly, being a cross-sectional study limits the conclusion on causal relationship between diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairment and its progression to dementia. Despite these limitations, the study provides insights about modifiable risk factors that may be included in the design of evidence-based prevention strategies needed to delay the development and progression of cognitive impairment.

References

- Jaul E, Barron J (2017) Age-Related Diseases and Clinical and Public Health Implications for the 85 Years Old and Over Population. Front public Health 5:335.

- Mavrodaris A, Powell J, Thorogood M (2013) Prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment among older people in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 91(10): 773-783.

- Knopman DS, Petersen RC (2014) Mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: a clinical perspective. Mayo Clin Proc Vol. 89(10): 1452-1459.

- de Souza-Talarico JN, de Carvalho AP, Brucki SMD, Nitrini R, Ferretti-Rebustini RE de. L (2016) Dementia and Cognitive Impairment Prevalence and Associated Factors in Indigenous Populations. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 30(3): 281-287.

- Ogunniyi A, Adebiyi AO, Adediran AB, Olakehinde OO, Siwoku AA (2016) Prevalence estimates of major neurocognitive disorders in a rural Nigerian community. Brain Behav 6(7): 481-489.

- Yusuf AJ, Baiyewu O, Sheikh TL, Shehu AU (2011) Prevalence of dementia and dementia subtypes among community-dwelling elderly people in northern Nigeria. Int psychogeriatrics 23(3): 379-386.

- World Health Organisation. Dementia fact sheets (2019).

- Rakesh G, Szabo ST, Alexopoulos GS, Zannas AS (2017) Strategies for dementia prevention: latest evidence and implications. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 8(9): 121-136.

- Arntzen KA, Schirmer H, Wilsgaard T, Mathiesen EB (2011) Impact of cardiovascular risk factors on cognitive function: The Tromsø study. Eur J Neurol 18(5): 737-743.

- Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, et al. (2013) The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 9(1): 63-75.

- Olayinka OO, Mbuyi NN (2014) Epidemiology of Dementia among the Elderly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Alzheimers Dis 1-15.

- Okokon IB, Asibong UE, Ogbonna UK, John EE (2018) Psychogeriatric Problems Seen in the Primary Care Arm of a Tertiary Hospital in Calabar, South-South Nigeria. Int J Geriatr Gerontol 1-9.

- Saedi E, Gheini MR, Faiz F, Arami MA (2016) Diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairments. World J Diabetes 7(17): 412-422.

- Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, et al. (2014) Association of diabetes with amnestic and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 10(1): 18-26.

- Cheng G, Huang C, Deng H, Wang H (2012) Diabetes as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Intern Med J 42(5): 484-491.

- Eze CO, Ezeokpo BC, Kalu UA, Onwuekwe IO (2015) The Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment amongst Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients at Abakaliki South-East Nigeria. J Metab Syndr 04(01): 1-3.

- Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, et al. (2015) Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement 11(6): 718-726.

- Adebiyi AO, Ogunniyi A, Adediran BA, Olakehinde OO, Siwoku AA (2015) Cognitive Impairment Among the Aging Population in a Community in Southwest Nigeria. Health Educ Behav 43(1): 93S-9S.

- Guerchet M, Mouanga AM, M belesso P, Tabo A, Bandzouzi B, et al. (2012) Factors Associated with Dementia Among Elderly People Living in Two Cities in Central Africa: The EDAC Multicenter Study. J Alzheimers Dis 29(1): 15-24.

- Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Kola L, Abiona T (2011) Incidence of and Risk Factors for Dementia in the Ibadan Study of Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(5): 869-874.

- Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S (1982) Measurement of Functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 37(3): 323-339.

- Teng E, Becker BW, Woo E, Knopman David S, Cummings Jeffrey L, et al. (2010) Utility of the Functional Activities Questionnaire for distinguishing Mild Cognitive impairment From Very Mild Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24(4): 348-353.

- Arizaga RL, Gogorza RE, Allegri RF, Baumann PD, Morales MC, et al. (2014) Cognitive impairment and risk factor prevalence in a population over 60 in Argentina. Dement Neuropsychol 8(4): 364-370.

- Dinesh G, Gursimran K, Akriti G (2019) Geriatric syndromes 2016.

- Hayden KM, Reed BR, Manly JJ, Tommet D, Pietrzak RH, et al. (2011) Cognitive decline in the elderly: An analysis of population heterogeneity. Age Ageing 40(6): 684-689.

- Palsetia D, Rao G, Tiwari S, Lodha P, De Sousa A (2018) The clock drawing test versus mini-mental status examination as a screening tool for dementia: A clinical comparison. Indian J Psychol Med 40(1): 1-10.

- Sheehan B (2012) Assessment scales in dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 5(6): 349-358.

- Egbi O, Ogunrin O, Oviasu E (2015) Prevalence and determinants of cognitive impairment in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study in Benin City, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 14(2): 75-81.

- Murman DL (2015) The Impact of Age on Cognition. Semin Hear 36(3): 111-121.

- Fisher GG, Chacon M, Chaffee DS (2019) Theories of cognitive aging and work. In: Work Across the Lifespan. Elsevier 17-45.

- Oghagbon EK, Giménez-Llort L (2019) Short height and poor education increase the risk of dementia in Nigerian type 2 diabetic women. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 11: 493-499.

- George-Carey R, Adeloye D, Chan KY, Paul A, Kolčić I, et al. (2012) An estimate of the prevalence of dementia in Africa: a systematic analysis. J Glob Health 2(2).

- Mayeda ER, Haan MN, Kanaya AM, Yaffe K, Neuhaus J (2013) Type 2 Diabetes and 10-Year Risk of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment Among Older Mexican Americans. Diabetes Care 36(9): 2600-2606.

- Lagos Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs). World Population Review (2020).

- Sakusic A, O’Horo JC, Dziadzko M, Volha D, Ali R, et al. (2018) Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors for Long-Term Cognitive Impairment After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review. Mayo Clin Proc 93(1): 68-82.

- World Health Organization. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines (2020).

- Yusuf AJ, Baiyewu O, Bakari AG, Garko SB, Jibril ME-B, et al. (2018) Low education and lack of spousal relationship are associated with dementia in older adults with diabetes mellitus in Nigeria. Psychogeriatrics 18(3): 216-223.

- Charan J, Biswas T (2013) How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med 35(2): 121-126.

- Tianyi FL, Agbor VN, Njamnshi AK, Atashili J (2019) Factors associated with the prevalence of cognitive impairment in a rural elderly cameroonian population: A community-based study in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 47(1-2): 104-113.

- Yusuf AR, Alabi KM, Odeigha LO, Wahab KW, Obalowu IA, et al. (2019) Cognitive impairment among type 2 diabetic patients attending family medicine clinics, university of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, north central Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Family Practice 10(3): 26-33.

- Baye D, Amare DW, Andualem M (2017) Cognitive impairment among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. J Public Heal Epidemiol 9(11): 300-308.

- Arizaga RL, Gogorza RE, Allegri RF, Baumann PD, Morales MC, et al. (2014) Cognitive impairment and risk factor prevalence in a population over 60 in Argentina. Dement Neuropsychol 8(4): 364-370.

- Tiwari SC, Tripathi RK, Farooqi SA, Kumar R, Srivastava G, et al. (2012) Diabetes mellitus: A risk factor for cognitive impairment amongst urban older adults. Ind Psychiatry J 21(1): 44-48.

- Xiu S, Liao Q, Sun L, Chan P (2019) Risk factors for cognitive impairment in older people with diabetes: a community-based study. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 10: 1-11.

- Teixeira MM, Passos VMA, Barreto SM, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, et al. (2020) Association between diabetes and cognitive function at baseline in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA- Brasil). Sci Rep 10(1): 1-10.

- Zhang MY, Katzman R, Salmon D, Jin H, Cai GJ (1990) He prevalence of dementia and Alzeheimer’s disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender, and education. Ann Neurol 27(4): 428-437.

- Li W, Sun L, Li G, Xiao S (2019) Prevalence, influence factors and cognitive characteristics of mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Aging Neurosci 11: 180-186.

- Ren L, Zheng Y, Wu L, Gu Y, He Y, et al. (2018) Investigation of the prevalence of Cognitive Impairment and its risk factors within the elderly population in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep 8(1): 3575-3583.

- Odeigah LO, Rotifa SU, Oligbu P, Okeke K (2020) Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in a Primary Care Setting of A Tertiary Hospital in North Central Nigeria. MedRead J Fam Med 1(3): 1013.

- Jamalnia S, Javanmardifard S, Akbari H, Sadeghi E, Bijani M (2020) Association Between Cognitive Impairment and Blood Pressure Among Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus in Southern Iran. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 13: 289-296.

- Sun L, Diao X, Gang X, Lv Y, Zhao X, et al. (2020) Risk factors for cognitive impairment in patients with type 2 diabetes. J diabetes Res.

- Yarube IU, Mukhtar IG (2018) Impaired cognition and normal cardiometabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes in Kano, Nigeria. Sub-Saharan Afr J Med 5(2): 37-44.

- Momtaz YA, Ibrahim R, Hamid TA, Chai ST (2015) Smoking and Cognitive Impairment Among Older Persons in Malaysia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 30(4): 405-411.

- Amer MS, Hamza SA, Abd El Rahman EE, Hamed HM, Zaki OK, et al. (2014) Relation between Smoking and Cognition in Egyptian Elderly. Egypt J Hosp Med 55(1): 239-244.

- Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Gamaldo AA, Teel A, Zonderman AB, et al. (2014) Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public health 14: 643.

- Formiga F, Ferrer A, Padrós G, Corbella X, Cos L, et al. (2014) Diabetes Mellitus as a Risk Factor for Functional and Cognitive Decline in Very Old People : The Octabaix Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15(12): 924-928.

- Momtaz YA, Hamid TA, Bagat MF, Hazrati M (2019) The Association Between Diabetes and Cognitive Function in Later Life. Curr Aging Sci 12(1): 62-66.