Head Injury, Concussion and Dementia - The Deadly Triad

Aisha Yousaf1* and Ashley Baldwin2

1Department of Psychiatry, Arundel Community Mental Health Team, Baird House, Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, Merseyside, United Kingdom

2Department of Psychiatry, Rydal Ward, Knowsley Resource and Recovery Centre, Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, Knowsley, Merseyside, United Kingdom

Submission: June 28, 2022; Published: July 26, 2022

*Corresponding author: Aisha Yousaf, Department of Psychiatry, Arundel Community Mental Health Team, Baird House, Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, Merseyside, United Kingdom

How to cite this article: Aisha Y, Ashley B. Head Injury, Concussion and Dementia - The Deadly Triad. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2022; 6(5): 555698. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2022.06.555698

Abstract

The link between head injury and Alzheimer’s disease is a contentious and evolving topic of debate. With the recent death from dementia of several former members of England’s 1966 Football World Cup winning team, there is an increasing focus on the long-term consequences of sports related head injury. Much of the emphasis has been on the impact of concussion on the health and welfare of athletes. This article will explore the effect of mild to severe traumatic brain injury and its connection with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The latter was diagnosed in more than a hundred former National Football League (NFL) players. We will scrutinize current literature from dementia studies that has suggested racial and ethnic differences in the trends in dementia prevalence. More funding is required to support further research into the link between Alzheimer’s disease and sports participation with the goal of prevention.

Keywords : Concussion; Alzheimer’s disease; Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE); Dementia Pugilistica; Traumatic brain injury (TBI); England’s 1966 World Cup; Chris Sutton; League of Denial: The NFL’s concussion Crisis; Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez

Introduction

The subject of brain injuries in football has come under the limelight in recent years following the premature death from dementia of several former members of England’s 1966 World Cup winning football team. Dementia (ICD-10: F00-F03), an umbrella term is a neurodegenerative disease which is usually chronic and progressive in nature; it is marked by disturbance of higher cortical functions, such as impaired memory, thinking, orientation and calculation. Changes in personality and compromised reasoning and judgement are also prevalent [1]. Five members of England’s World Cup team developed neurogenerative disease leading to the death of four of them between 2018 and 2020. These were Ray Wilson, Martin Peters, Jack Charlton (Bobby Charlton’s older brother) and Nobby Stiles; whereas Bobby Charlton was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2020 [2]. Their careers are believed to have been a contributory factor to their dementia. Bobby Charlton is one of the most famous English football players and is still considered as one of the best midfielders of all times. He played in four World Cups (1958, 1962, 1966 and 1970) and made a total of 106 international appearances for England - a national record at the time.

Over the last three decades, the number of individuals living with dementia has steadily increased [3]. In addition to its obvious morbidity, the syndrome has imposed a huge burden on health and social care systems worldwide; impacting countless families and communities negatively. In 2016, the global population with dementia was 43.8 million. This increased from 20.2 million in 1990 and the trend is expected to increase in the future [3-4]. Until mitigative or curative treatments become available, dementia will constitute a mounting challenge to the public health globally. There are various recognized risk factors for dementia. Some of them are modifiable, such as low education, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, depression, smoking, alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, hearing loss, loneliness, heart disease, stroke, Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), and delirium [5-6]. Other risk factors such as age, sex and genetic predisposition (e.g. APOE ε4 genotype) are non-modifiable [6].

The link between head injury and dementia remains controversial and is considered to be complex. Although there appears to be a connection between traumatic brain injuries and augmented risk of dementia; not everyone who has had head injury is believed to progress to developing dementia. Athletes in contact sports such as football, rugby, American football, ice hockey, boxing, wrestling, skiing in addition to military veterans have an increased risk of experiencing multiple head injuries compared to general population [7-8]. Several studies have documented variances in dementia prevalence among racial and ethnic groups with Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) group and Hispanics being at a higher risk of dementia compared to Caucasian populations [9-11]. In October 2019, FIELD study was published by the University of Glasgow which revealed that male footballers were around three and- a-half times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than the general population [12]. But what about the females? It is noted that there is an under-representation of women in studies which can possibly be because their sports are still developing. A prospective cohort study published in the journal of Alzheimer’s Association in 2021 included 14,376 participants with twentyfive years follow-up. It showed that females are at greater risk of dementia after head injury compared to males. It conversely showed Caucasian populations to be at greater risk of developing dementia compared to BAME group [13].

Research continues to show greater risk of concussions and head injuries in women. Theories are put forward to explain this increasing risk. These include potential alterations in the microstructure of the brain to the influence of hormones, differences in neck strength, players’ experience level, coaching regimes, and the management of injuries [14]. It is noted that not only the quantity of head injuries differs between women and men, but also their nature. A review of twenty-five studies of sport-related concussion suggests that female athletes are not only more vulnerable to concussion than males, but are also susceptible to more severe concussions - thus increasing the risk of neurogenerative disease [15].

Sue Lopez was one of the most noticeable woman football players in 1970s. She spent her entire club career playing for Southampton Women’s Football Club, except for a season in Italy’s Serie A with Roma in 1971. She was diagnosed with dementia in 2018. Sue publicly blames her dementia on years of heading the ball resulting in her suffering several concussions during her sporting career between 1966 and 1985. She urges young footballers to stop heading the ball due to increase risk connected with receiving concussions and dementia [16].

Sports-related traumatic brain injury is becoming a significant public health crisis. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is considered as a major cause of disability and morbidity in the United States of America. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a hundred and seventy-six Americans dying from TBIrelated injuries each day [17]. In England and Wales, around 1.4 million patients per year attend hospital following head injury and it is thought to be the most common cause of death under the age of 40 years [18-19]. Traumatic brain injuries vary in severity from mild, transient symptoms to protracted periods of altered consciousness. Moderate to severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is considered to be one of the strongest and well-established modifiable risk factors for the development of neurodegenerative diseases such as late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [20].

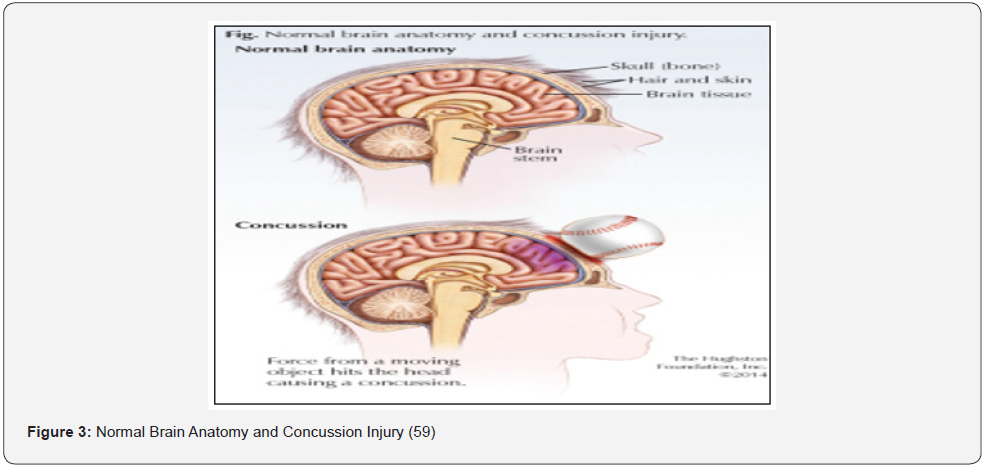

The disability may persist for years after the initial injury in survivors. Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI) on the other hand is usually of self-limited nature. Even though minor head injuries can also have consequences (e.g. confusion, sensitivity to light, migraine, depression); it holds a better prognosis, as most patients experience complete resolution of symptoms. mTBI is often used interchangeably to refer to a concessional injury. In the context of brain injuries in sports, the term ‘concussion’ (ICD 10 code: S06.0) is frequently used; which is essentially a subset of the more sinister sounding mTBIs. There is no universal definition of a concussion. It is in practice a biomechanically induced transient disturbance of neurologic function that may or may not be associated with loss of consciousness [21]. Concussion is a risky condition, and its early detection and management is of great importance as mismanagement and/or neglect can lead to a complex sequalae of neuropsychiatric disorder [22].

Although extensive research has focused on the increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases associated with moderate to severe brain injuries, emerging data proposes that mild head injuries, particularly repeated mild injuries, may also pose as a risk factor [23]. Research in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans in 2017 showed that ‘repetitive’ mild traumatic brain injury is associated with a higher risk of neurodegeneration and reduced memory performance in individuals at greater genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. These results demonstrate the importance of documenting head injuries even within the mild range as they may interact with genetic risk to produce negative long-term health consequences such as neurodegenerative disease [24-26].

Historically, concussion was a phrase that was never regarded as significant and was used very lightly in mainstream media coverage. However, with the deaths of high-profile World Cup winning footballers, a visible change in media perception of concussion and head injuries in sport has emerged [27-28]. Concussion is now recognized as one of contact sport’s greatest challenges as well as a potential risk factor for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) [29]. Much of the media focus has been given to link the impact of concussion on the health and welfare of athletes. This attention was mostly driven by the generation of enlightening conversations inspired by some of the highprofile films such as the Will Smith movie “Concussion” and documentaries such as “League of Denial: The NFL’s concussion Crisis” and “Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez”.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and CTE have long been recognized as sharing some parallel neuropathological qualities, predominantly the accumulation of pathognomonic hyperphosphorylated tau protein and shrinkage in the hippocampus. Though research has established that CTE has an inimitable pattern of abnormal tau build up that is different from AD such that they are seen as discrete entities. Research done in 2015 summarises the differences in the distribution of hyperphosphorylated tau in both CTE and AD [30]. Findings are now emerging that CTE and AD may be present in the same patients and there are ongoing debates whether TBI can specifically lead to Alzheimer’s like disease, or whether CTE can cause AD following TBI [31-33]. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative syndrome, associated with single, episodic, or repetitive blunt force impacts to the head and transfer of acceleration-deceleration forces to the brain [34]. Those at maximum risk for CTE are athletes who play contact sports and military veterans, possibly due to their added chances of enduring recurrent blows to the head [35]. CTE is a rare disorder, and its diagnosis can only be done posthumously (at autopsy by studying sections of the brain) as unfortunately no reliable biomarkers of this disorder are available.

CTE was previously known as Dementia pugilistica (the term was derived from the Latin word pugil, which translates as “boxer” or “fighter”) or punch-drunk syndrome since it was originally described in 1920s’ boxers. They were thought to have suffered multiple concussions leading to the decline in mental ability, with impaired memory, lack of coordination and Parkinson’s disease like symptoms (due to biomechanical trauma to similar sub cortical areas of the brain). Other terms used were ‘‘Chronic Boxer’s Encephalopathy’’, ‘‘Traumatic Boxer’s Encephalopathy’’, and a subtype of Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury or CTBI. These terms are no longer used because it is now known that the condition is not restricted to ex-boxers and is also diagnosed in relation to contact sports and military personnel [36]. Mohammed Ali, possibly the greatest heavyweight boxer of all times was believed to suffer from Dementia Pugilistica, and it is thought that he died of its complications in June 2016 [37-38].

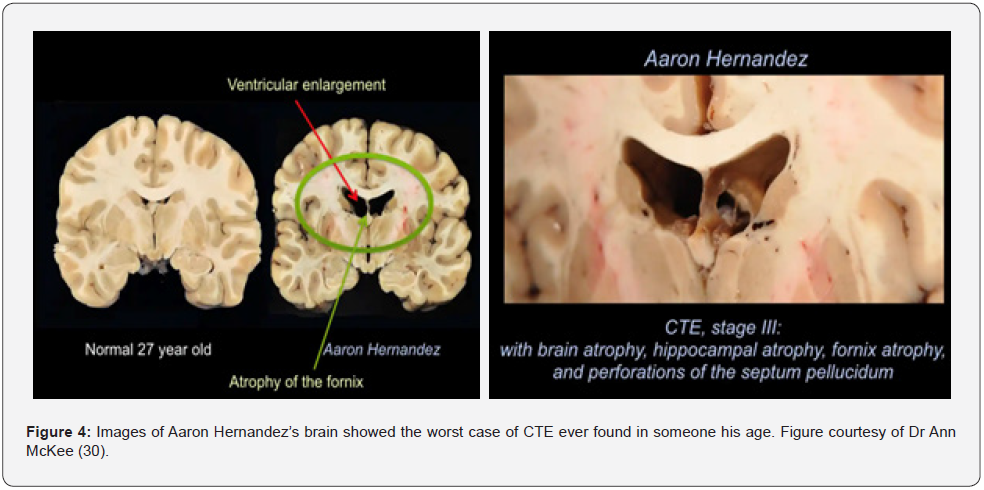

Aaron Hernandez, a former NFL (National Football League) player and a convicted murderer was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. He committed suicide in April 2017 at the age of 27 while serving life in prison for murder. He was believed to suffer from a substantial damage to the key parts of the brain, including the hippocampus - central to memory creation and storage, as well as the frontal lobe – which has a pivotal role in problem solving, judgement, impulse control and behaviour [39]. Autopsy on his post-mortem brain was performed by Boston University researchers, led by Dr Ann McKee and showed that he suffered from a severe form of the degenerative brain disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy [40,30]. The brain autopsy findings were described as the most severe case of CTE seen in someone of Aaron’s age [41]. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy has been found in more than a hundred former N.F.L. players, some of whom committed suicide with others suffering from mental health problems such as depression, anxiety or other mood and behavioral disorders [42-44]. This raises a thoughtprovoking question: Is there a link between TBI and suicide? Although we must not forget that sports players are not immune to mental health issues manifesting for similar biopsychosocial reasons or majority of supplementary risk factors present in the general population

There seems to be an association between a single TBI and the development of dementia. Research has shown that even a single episode of TBI can lead to the development of neurofibrillary tangle pathologies; which are essentially the aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. These tau proteins are pathognomonic of both AD and CTE [45-46]. A player can expect to play a number of games each season in addition to intense and exhausting weekly training routines. When considering the number of direct head contacts and the impact of the resultant high forces on the brain of a player during games and training, it is easy to understand the greater risk of receiving repeated concussions and through these, neurodegenerative diseases - compared to the general population [47-48].

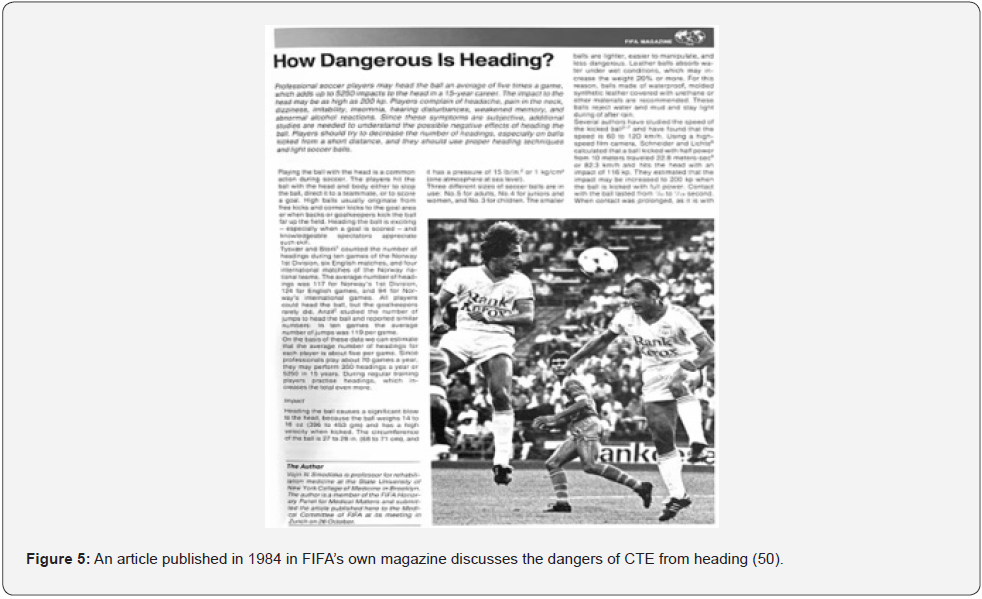

There are reports of footballers suffering from brain damage as early as September 1903. Sam Nicholls, a former English footballer who won the 1892 FA Cup Final was believed to be in a serious condition due to his persistency of heading the balls [49]. FIFA (the International Federation of Association Football) published an article in the FIFA magazine titled ‘How Dangerous Is Heading?’ in 1984; this revealed the apparent connection between football game and brain damage [50]. The article was presented to the FIFA Medical Committee at a meeting in Zurich on 26 October 1984. It is disappointing that these early red flags were not appreciated and acted upon. There remained a slow commitment within professional football to recognise and admit the link between brain injury and the sport. The rising concerns regarding the alleged link between contact sports and the development of CTE and Alzheimer’s disease have resulted in increasing academic attention focussed on sporting injuries. Ongoing media coverage and awareness has amplified public awareness of sports-related head injuries. A noticeable shift in media attitudes has therefore been detected towards concussion and head injuries in contact sports.

In Rugby, repeated blows to the head suffered on the field, from colliding with other players is thought to be the cause of the irreversible damage [51]. The Rugby Football Union admits that it poses a ‘significant potential risk of concussion’. It says there is one incident in every three professional matches [52]. More and more players are joining legal action against rugby union’s governing bodies, condemning negligence over head injuries. This unfortunately includes one of the prominent names of Adam Hughes who retired with brain injury at the age of only 28. He is thought to be on path to early-onset dementia [53-54].

Chris Sutton – former international professional football player, Celtic FC legend, former Lincoln City manager and later TV/Radio commentator has campaigned hard to raise awareness of the connection between heading in football and dementia. His father and mentor Mike Sutton, who was also a professional footballer, died of dementia in December 2020. Chris Sutton’s efforts have been pivotal is raising funds for extended research into the deadly triad of head injury, concussion and dementia. He has advocated that players who receive blow on their heads during the game need to be properly assessed in a dressing room by an independent doctor before they can carry on. He called for rule makers IFAB (International Football Association Board) for immediate ratification of temporary substitutes [55]. Risk is a recognised part of any contact sport. Yet, sport clubs have a duty of care to guard their players by implementing their own concussion protocols and minimise their risk of being exposed to injury.

Especially if this is reasonably anticipatable. With an increasing profile, there are now welcomed conversations and changes in relation to dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases.

It is time we consider a more focused question be asked about head injuries and dementia; especially in high-risk sports such as boxing and the NFL: Is heading necessary to the game of football? During the summer of 2021, the Football Association (the FA) declared that from the start of the 2021/2022 season, English football will introduce heading guidance across all levels of professional and amateur football games, with a particular focus on training sessions [56]. Healthier communication is a prerequisite with a player’s treating team if a brain injury is suspected, with appropriate medical intervention and aftercare. The take home message is that sports related concussion is common and carries long term risks. It can lead to complex neuropsychiatric disorder. Concussion is cumulative and can affect nearly any aspect of players’ lives. It cannot be ignored as absent or incomplete management of head injuries may result in ongoing symptoms, more concussions and other injuries. Advocacy is an issue that should not exclusively be limited to professional sportsmen; but a very common problem in amateur and youth sports [57]. This is an alarming prospect for parents in trying to decide whether to allow their children to participate in sports or not. It is crucial to maintain a healthy balance between the benefits of the games on one hand and the risks and lifelong damages on the other.

References

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK. Dementia (2007) Dementia: A NICE-SCIE Guideline on Supporting People With Dementia and Their Carers in Health and Social Care.

- Sky Sports - Boys of ’66 and dementia.

- Nichols E, Szoeke CE, Vollset SE, Abbasi N, Abd-Allah F, et al. (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18(1): 88-106.

- GBD 2019 (2022) Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7(2): e105-e125.

- Yaffe K (2018) Modifiable risk factors and prevention of dementia: what is the latest evidence?. JAMA Intern Med 178(2): 281-282.

- Willoughby KA (2021) A Multidisciplinary Analytical Approach to the Identification of Both Modifiable and Non-Modifiable Risk Factors of Dementia (Doctoral dissertation, Colorado State University)

- Baugh CM, Stamm JM, Riley DO, Gavett BE, Shenton ME, et al. (2012) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: neurodegeneration following repetitive concussive and subconcussive brain trauma. Brain Imaging Behav 6(2): 244-254.

- Stewart W (2021) Sport associated dementia. BMJ 372.

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, et al. (2007) Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology 29(1-2): 125-132.

- Yaffe K, Falvey C, Harris TB, Newman A, Satterfield S, et al. (2013) Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: prospective study. BMJ 347.

- Pham TM, Petersen I, Walters K, Raine R, Manthorpe J, et al. (2018) Trends in dementia diagnosis rates in UK ethnic groups: analysis of UK primary care data. Clin Epidemiol 10: 949-960.

- Russell ER, Stewart K, Mackay DF, MacLean J, Pell JP, et al. (2019) Football’s Influence on Lifelong health and Dementia risk (FIELD): protocol for a retrospective cohort study of former professional footballers. BMJ open. 9(5): e028654.

- Schneider AL, Selvin E, Latour L, Turtzo LC, Coresh J, et al. (2021) Head injury and 25‐year risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 17(9): 1432-1441.

- Why sports concussions are worse for women.

- McGroarty NK, Brown SM, Mulcahey MK (2020) Orthop. J Sports Med 8.

- Dailymail: Ex-England women's footballer Sue Lopez, 74, blames her dementia diagnosis on heading the ball as a child and urges a ban for under-12s.

- Traumatic Brain Injury and concussion - CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance (2014) Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in children, young people and adults. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK).

- Lawrence T, Helmy A, Bouamra O, Woodford M, Lecky F, et al. (2016) Traumatic brain injury in England and Wales: prospective audit of epidemiology, complications and standardised mortality. BMJ open. 6(11): e012197.

- Maas AI, Menon DK, Adelson PD, Andelic N, Bell MJ, et al. (2017) Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol 16(12): 987-1048.

- Giza CC, Difiori JP (2011) Pathophysiology of sports-related concussion: an update on basic science and translational research. Sports Health 3(1): 46-51.

- Jordan BD (2013) The clinical spectrum of sport-related traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol 9(4): 222-230.

- Vincent AS, Roebuck‐Spencer TM, Cernich A (2014) Cognitive changes and dementia risk after traumatic brain injury: implications for aging military personnel. Alzheimers Dement 10(3 Suppl): S174-187.

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, Spielberg JM, Verfaellie M, et al. (2017) Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 140(3): 813-825.

- Barnes DE, Byers AL, Gardner RC (2018) Association of mild traumatic brain injury with and without loss of consciousness with dementia in US military veterans. JAMA Neurol 75(9): 1055-1061.

- Bloom BM(2019) Assessment and outcomes in mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. London: William Harvey Research Institute, Queen Mary University of London.

- The Guardian: Why are so many former footballers suffering from dementia. Nov 2020.

- Parry KD, White A, Anderson E, Batten J (2021) The shifting media discourse surrounding head injuries in association football. Academia Letters 13: 1-8.

- Figure 5: New images show Aaron Hernandez suffered from extreme case of CTE

- Ramalho J, Castillo M (2015) Dementia resulting from traumatic brain injury. Dement Neuropsychol 9(4): 356-368.

- Shively S, Scher AI, Perl DP, Diaz-Arrastia R (2012) Dementia resulting from traumatic brain injury: what is the pathology?. Archives of neurology. 69(10): 1245-1251.

- Turner RC, Lucke-Wold BP, Robson MJ, Lee JM, Bailes JE (2016) Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Distinct but possibly overlapping disease entities. Brain Inj 30(11): 1279-1292.

- Baugh CM, Stamm JM, Riley DO, Gavett BE, Shenton ME, et al. (2012) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: neurodegeneration following repetitive concussive and subconcussive brain trauma. Brain Imaging Behav 6(2): 244-254.

- McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, et al. (2009) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 68(7): 709-735.

- Castellani RJ, Perry G (2017) Dementia pugilistica revisited. J Alzheimers Dis 60(4): 1209-1221.

- Lolekha P, Phanthumchinda K, Bhidayasiri R(2010) Prevalence and risk factors of Parkinson's disease in retired Thai traditional boxers. Mov Disord 25(12):1895-1901.

- The Complicated Link Between Muhammad Ali’s Death and Boxing

- Henne K, Ventresca M (2020) A criminal mind? A damaged brain? Narratives of criminality and culpability in the celebrated case of Aaron Hernandez. Crime, Media, Culture 16(3): 395-413.

- Bisht R (2020) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Understanding the Disease and Its Impact on Football. Science.

- New York Post - Aaron Hernandez autopsy revealed ‘severe’ case of CTE, lawyer says

- Moran B (2017) CTE found in 99 percent of former NFL players studied. Boston University.

- Didehbani N, Munro Cullum C, Mansinghani S, Conover H, Hart J (2013) Depressive symptoms and concussions in aging retired NFL players. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 28(5): 418-424.

- Webner D, Iverson GL (2016) Suicide in professional American football players in the past 95 years. Brain Inj 30(13-14): 1718-1721.

- Zanier ER, Bertani I, Sammali E, Pischiutta F, Chiaravalloti MA, et al. (2018) Induction of a transmissible tau pathology by traumatic brain injury. Brain 141(9): 2685-2699.

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2012) Widespread tau and amyloid-beta pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol 22(2):142-149.

- Niedfeldt MW (2011) Head injuries, heading, and the use of headgear in soccer. Curr Sports Med Rep 10(6): 324-329.

- Manley G, Gardner AJ, Schneider KJ, Guskiewicz KM, Bailes J, et al. (2017) A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion. Br J Sports Med 51(12): 969-977.

- Football League’s heading fears…in 1966: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/daily-mail/20211007/283244511144604

- How Dangerous Is Heading.

- Stewart W, McNamara PH, Lawlor B, Hutchinson S, Farrell M (2016) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late and under recognized consequence of rugby union?. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 109(1): 11-15.

- Headcase general Information.

- Dyer C. Rugby players plan negligence claim for chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

- Adam Hughes and Head injury: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/rugbyunion/article-9064531/Adam-Hughes-speaks-head-injury-ordeal-retiring-rugby-union-28.html

- Chris Sutton: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-10549387/CHRIS-SUTTON-disappointed-Michael-Owen-said-concussion-rules.html

- Football and Dementia: https://www.stewartslaw.com/news/football-and-dementia-are-players-getting-enough-protection-against-the-risks-of-brain-injury/

- Moreno MA, Furtner F, Rivara FP (2012) Youth sports and concussion risk. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166(4): 396.

- Figure 1: News: Jack Charlton: Leeds and Ashington legend remembered.

- Figure 3: Hughston Clinic: Concussions & ImPACT Testing Guidelines for Athletes (2014).

- Figure 7: The Telegraph: Chris Sutton exclusive: My dad's dementia battle a reminder of why we must act over 'national disgrace'