Comparison of the Occurrence of Hospitalization Between Frail, Vulnerable and Non-Frail Older Adults Attended by Primary Health Care Units

Isabella Rodrigues Esteves1, Dayane Barboza de Lira2, Izabela Silva Santos Ferreira2, Maíra Benício Pouza2, Sheila de Melo Borges3*

1Student at the Faculty of Physiotherapy and the Scientific Initiation Program, Santa Cecilia University (UNISANTA), Brazil

2BSc. Lato Senso Graduate Student in Adult and Pediatric Intensive Physiotherapy, Santa Cecilia University (UNISANTA), Brazil

3Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Physiotherapy, Santa Cecilia University (UNISANTA), Brazil

Submission: June 14, 2021; Published: June 24, 2021

*Corresponding author: Sheila de Melo Borges, Faculty of Physiotherapy of Santa Cecilia University (UNISANTA), Brazil

How to cite this article: Isabella Rodrigues Esteves, Dayane Barboza de Lira, Izabela Silva Santos Ferreira, Maíra Benício Pouza, Sheila de Melo Borges. Comparison of the Occurrence of Hospitalization Between Frail, Vulnerable and Non-Frail Older Adults Attended by Primary Health Care Units. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2021; 6(1): 555680. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2021.06.555680

Abstract

Objective: Compare the occurrence of hospitalization in the preceding 12 months among frail, vulnerable and non-frail older adults attended at primary health care units.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 298 older adults who attended primary health care units in Santos, SP, Brazil, divided into three groups classified according to the Edmonton Frailty Scale: non-frail (n=161), vulnerable (n=78) and frail older adults (n=59). To achieve the study aims, we analyzed information regarding the occurrence and number of hospitalizations reported by older adults, and/or their companions, in the preceding 12 months.

Results: The Chi square test showed a significant difference in hospitalizations (p =0.016), with higher frequency among frail older adults (n=11; 18.6%), followed by vulnerable (n=11; 14.1%) and non-frail older adults (n=10; 6.2%). A significant difference was also observed regarding the number of hospitalizations (p =0.038), where one report of hospitalization was more common among frail (n=8; 13.6%) and vulnerable older adults (n=10; 12, 8.0%) than non-frail older adults (n=7; 4.3%).

Conclusion: Hospitalization prevalence was low in the three groups studied, though it was a more frequent outcome among vulnerable and frail older adults, particularly the latter, than for non-frail older adults.

Keywords: Older Adults; Frailty; Vulnerability; Primary Health Care; Hospitalization

Abbreviations: EFS: Edmonton Frailty Scale; SUS: Brazil’s Unified Health System

Introduction

With the increase in life expectancy experienced worldwide, the aging of the population brings numerous challenges to ensure that older adults can access good quality of life [1]. Although it is possible to live more today than in past generations, chronic diseases that are related to age have not changed [2]. Thus, it is essential to identify and monitor frail adults or those at risk of frailty, since the frailty syndrome is related to advancing age [3,4]. Frailty is defined as a biological syndrome, in which there is a decrease in functional capacity, resulting in accumulative decline in the body, thereby causing vulnerability [5]. This condition is associated with greater dependence in activities of daily living, leading to the occurrence of adverse clinical outcomes, such as functional decline, falls, increased morbidity and mortality, institutionalization, and hospitalization [4]. Additionally, we know that primary care represents the entry point into the health care system for many older adults who may be pre-frail and frail and screening as well as managing frailty appear to be reasonable approaches to reducing disability in older persons [6].

In primary care, clinicians might have the opportunity to better manage co-existing conditions that underlie frailty and reduce stressors that could precipitate adverse outcomes, with the aim of averting potentially avoidable hospitalizations and others negatives consequencies such as caregiver distress, premature institutionalization, and early mortality [7]. Although necessary in many cases, the hospitalization represents a high risk to health, especially when prolonged and repeated [8]. According to some studies, [9-11] frailty increases the risk of mortality after six months of hospitalization and is associated with a higher occurrence of geriatric syndromes, including delirium, falls, depression, cognitive decline, and immobility. Given these factors and the importance of frailty and its consequences, this study sought to extend current knowledge concerning the relationship between frailty and hospitalization among this population. Thus, the purpose of this study was to compare the occurrence of hospitalization reported in the preceding 12 months among frail, vulnerable, and non-frail older adults attended at primary health care units.

Materials and Methods

Study design and Ethical Aspects

An analytical, observational, cross-sectional research was conducted using data from the thematic project entitled “Síndrome da fragilidade: Identificação e monitoramento de vulnerabilidade em idosos usuários de Unidades Básicas de Saúde no município de Santos/SP” [Frailty syndrome: Identification and monitoring of vulnerability in older adults who attended primary health care units in the municipality of Santos, SP], with the approval of the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings, under protocol CAAE: 36261214.8.0000.5513 (opinion: 828.776), and following the recommendations of Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council.

Study population

For the thematic study on the frailty syndrome, the sample calculation considered the prevalence of frailty to be 23.8%, [12] and type I error was admitted in 5% (α = 0.05) with a statistical power of 95% (1 – ß = 0.95), resulting in a sample of at least 276 participants. Data from 305 older adults were collected; however, following the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 298 older adults who attended primary health care units in the city of Santos, SP, Brazil, participated in this study. They were divided into three groups, frail (n = 59; 19.8%); vulnerable (n = 78; 26.2%) and non-frail (n = 161; 54%), based on the results of the Edmonton Frailty Scale (EFS). The inclusion criteria were adults aged 60 years old or over, of either sex, who signed the informed consent form. The exclusion criterion was anyone who did not complete the questionnaire.

Procedures

The older adults who attended primary health care units in the municipality of Santos, from the neighborhoods Aparecida, Bom Retiro, Boqueirão, Embaré, Gonzaga and Ponta da Praia, who were at one of these Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) units at the time of the research for whatever reason (getting vaccinated, a consultation, making an appointment, ending a prescription medication), were invited to participate in the study at the time or were scheduled to participate on another day of their preference. After explaining the research, agreeing to participate, and signing the informed consent form, the older adults were evaluated by physiotherapy students, supervised by the person in charge of the research and/or by a physiotherapist (project collaborator). The exam took place in the primary health units, in a space assigned by the person in charge of each unit, during 2014 and 2016. Regarding data collection for the thematic project on frailty, mentioned above, a research protocol was applied based on the Caderneta da Pessoa Idosa [13] [Booklet for Older Adults] and the Caderno de Atenção Básica da Pessoa Idosa [14] [Notebook on Primary Care for Older Adults], both elaborated by the Ministry of Health. In addition, the EFS was also applied. To achieve the aims of this study, information from the sociodemographic questionnaire and health status were used to characterize the sample, in addition to questions concerning hospitalization and the results of the EFS.

Research Tools

The following data were used to characterize the sample: sex, age, years of education, number of diseases, and number of medications. In addition, the participants were asked about the occurrence of hospitalization and the number of hospitalizations in the preceding 12 months, retrospectively. It is important to highlight that all the proposed evaluations were self-reported. Thus, the responses of participants with suspected cognitive impairment assessed by cognitive screening tests or with a clinical diagnosis of dementia were confirmed by a companion.

The EFS assesses nine domains involving the following aspects: cognition, through the application of the Clock-Drawing Test; general health status; functional independence; social support; use of medication; nutrition; humor; continence; and functional performance, assessed using the Timed Up and Go Test [15,16]. The maximum EFS score is 17 points, which represents the highest level of frailty; a score of 0 to 4 indicates the absence of frailty; a score of 5 or 6 indicates the person is apparently vulnerable; 7 or 8, mild fragility; 9 or 10, moderate fragility; and 11 or more points indicate severe frailty [15,16]. To achieve the aims of this study, the group of frail older adults was composed of those who obtained a score of 7 or more points (EFS), that is, older adults with mild, moderate and severe fragility were all assigned to one group. The group of non-frail older adults was composed of those classified with “absence of frailty”, and the group of vulnerable older adults was composed of those classified as “apparently vulnerable” (EFS).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the statistical software SPSS® version 25.0 for Windows. The numerical data were presented as median values with minimum and maximum, and the nominal data were presented as the means of relative and absolute frequency. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to assess the premise of normality for numerical data. For comparative analysis, Kruskal-Wallis was used for numerical data, since all numerical variables were asymmetric, while categorical data were analyzed using the Chi square test. Bonferroni’s post hoc correction was used to identify which peer comparisons between groups were significantly different from each other. In addition, the covariance model (ANCOVA) was used to assess the potential for confounding variables to affect the results obtained. A value of p <0.05 was used to determine significance.

Results

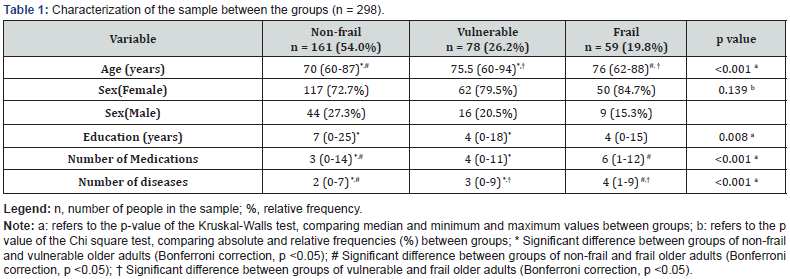

There was a significant difference in the variables age (p <0.001), education (p=0.008), number of medications taken (p <0.001) and number of diseases (p <0.001) between the groups studied (Table 1). Regarding age, frail and vulnerable older adults (median, 76 and 75.5 years old, respectively) were older compared with non-frail older adults (median, 70 years old), and post hoc analysis showed a significant difference between these groups (p <0.05). Education was lower among the groups of frail and vulnerable older adults, with a median of 4 years of education, compared with non-frail older adults (median, 7 years); however, post hoc analysis only showed a significant difference (p <0.05) between non-frail and vulnerable older adults. When analyzing the number of diseases and use of medication, the group of frail older adults reported a median of four diseases and the use of six medications, vulnerable older adults reported a median of three diseases and the use of four medications, and non-frail older adults reported a median of two illnesses and the use of three medications. Post hoc analysis showed the groups were significantly different from each other (p <0.05) only in relation to the number of diseases. Regarding the use of medications, no difference was observed between vulnerable and frail older adults, though these groups were significantly different (p <0.05) compared with non-frail older adults. No significant difference was observed in relation to sex (p =0.139), even though female older adults were more prevalent in all three groups (Table 1).

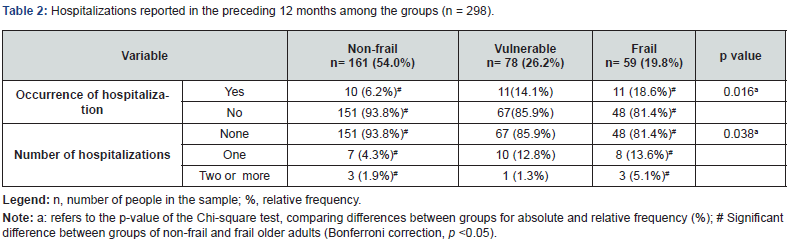

Significant differences were observed in the occurrence of hospitalization (p = 0.016), and the number of hospitalizations (p = 0.038) in the preceding 12 months (Table 2). Although the majority of the participants in the three groups reported no hospitalization in that period, the frequency of hospitalization was higher among frail older adults (n = 11; 18.6%), followed by vulnerable older adults (n = 11; 14, 1%), and finally non-frail older adults (n = 10; 6.2%). Reports of a single hospitalization were more frequent among frail (n = 8; 13.6%) and vulnerable older adults (n = 10; 12.8%) than among non-frail older adults (n = 7; 4.3%), while reports of two hospitalizations were more frequent among frail older adults (n = 3; 5.1%) than vulnerable (n = 1; 1.3%) and non-frail older adults (n = 3; 1.9%). Post hoc correction only showed a significant difference (p <0.05) between the nonfrail and frail groups, both in the occurrence and in the number of hospitalizations. In addition, the occurrence of hospitalization remained significant [F (2,277) = 4,270; p = 0.020] after adjusting for the variables age, education, number of diseases and use of medications (Table 2).

Discussion

Fried et al. [17] affirmed that the prevalence of frailty increases as age advances and determined older adults are at greater risk for their health, including mortality, institutionalization, falls, and hospitalization. However, even though frailty is associated with age, the evidence does not support broad generalizations because not all older adults are frail [18]. This study corroborates these findings, since among the 298 participating older adults, 161 were non-frail; thus, more than half of the participants did not show frailty. Nevertheless, according to Schuurmans et al.,[18] higher mean age contributes to the worsening of chronic diseases, exacerbating these more frequently, which increases the chances of frailty. According to some studies [17,19] the higher the chronological age, the greater the risk of the occurrence of frailty, a fact corroborated by the profile of the participants in this study, where the median age of frail older adults was 76 years old, vulnerable older adults was 75.5 years old, while that of non-frail older adults was 70 years old. Moreover, this research observed that in addition being older, vulnerable and frail older adults had a lower level of education, reported more diseases, and showed greater use of medications compared with non-frail older adults. Regarding the use of medications in older adults, a study by Pagno et al. [19] showed that concomitant use of more than five medications doubled the risk of frailty, a finding that is consistent with this study, which verified that frail older adults reported a median use of six medications, while non-frail older adults reported the use of three medications. According to Sousa et al. [20] medications improve the health and wellbeing of older adults; however, problems often occur due to drug interactions, inappropriate drugs, and the use of multiple drugs (polypharmacy), particularly in frail older adults [21]. Faced with this perspective, regarding adverse reactions from drugs, it is important to consider not only their high prevalence in the older adult population, but also the costs generated and their epidemiological importance as a possible cause of hospitalization [20].

When analyzing the variable education and how it affects the health of older adults, Chen et al. [22] pointed out that education contributes to a greater cognitive reserve, improving adequation to numerous situations. Thus, according to Brigola et al. [23] education is one of the predisposing factors for frailty, since they observed that frail and pre-frail older adults had less education compared with non-frail older adults, a finding that corroborates the data obtained in this present study. We verified that frail and vulnerable older adults had a median of four years of education, which was lower than non-frail older adults, who had a median of seven years. Another factor that characterizes the sample, which can also be decisive in relation to health care and health status concerns the process of the “feminization of old age” [24]. This condition was observed herein, with a predominance of women in all three study groups. This process occurs due to the higher life expectancy of women compared with men [25] in addition to factors like the differences in exposure to occupational risks, higher mortality rates due to external causes among men, difference in lifestyles regarding alcohol and tobacco, and the fact that women are more likely to seek health care services [26,27]. Regarding hospitalization, despite the low frequency of reports of hospitalization in the preceding 12 months in the groups studied, the prevalence showed a significant increase among vulnerable (14.1%) and frail (18.6%) older adults. Indeed, the sum of the occurrence of hospitalizations for these two groups is a hospitalization rate of 32.7%, compared with just 6.2% among non-frail older adults. A study by Remor et al. [28] also observed a low frequency of hospitalization. The authors observed that in a population of 100 older adults, only 27% required hospitalization, and of these, frail older adults showed more occurrences and a higher number of hospitalizations compared with pre-frail and non-frail older adults.

In addition, frail older adults showed a higher frequency both in reports of a single hospitalization and two or more hospitalizations [28]. Another Brazilian study from 2019 [29], reported a higher frequency of hospitalization in frail older adults, where the occurrence was observed in 54.9% of the population. An international study, published in the same year [8] indicated a prevalence of frailty from 31.9% to 35.4% in hospitalized older adults, depending on the instrument used to assess the syndrome. It is worth highlighting that in this study, we also observed that a single hospitalization was more common in relation to two or more hospitalizations, and that these situations where most frequent among frail older adults, followed by vulnerable older adults. Recent study has reported that hospital readmission is associated with frailty syndrome [30] a fact observed in this study.

According to Freire et al. [31] hospitalization is an important resource in the care of older adults; however, when prolonged and repeated, it can produce negative consequences for their health, including decreased functional capacity and quality of life, and increased frailty. Following this line of reasoning, a systematic review [32] showed that frailty is a risk factor for hospitalization, for increased length of stay, and for hospital readmission. Furthermore, regarding the consequences that hospitalization can cause in the older adult population, especially for those who are already frail, comparisons between the groups studied here (frail vs vulnerable, frail vs non-frail, and vulnerable vs non-frail) showed a significant difference was only observed a between frail and non-frail older adults, while the occurrence and number of hospital admissions was similar between frail and vulnerable older adults. According to Cunha et al. [32] vulnerable older adults must be identified, since they are more susceptible to evolving to frailty than returning to non-frail status. We also highlight the importance of studies and early intervention proposals for this population, since in relation to variables like the use of medications and education, and the occurrence and number of hospitalizations, no significant differences were observed between frail and vulnerable older adults, following post hoc correction, in contrast to that observed for the non-frail group.

It is worth emphasizing that comparisons between the variable study outcomes in relation to hospitalization was significant among the three groups, despite the low occurrence of hospitalization in the population studied as a whole. Moreover, participation was lower among frail and vulnerable older adults compared with non-frail older adults. The baseline study [12] for the sample calculation of the thematic project on frailty observed a prevalence of 23.8% for frail older adults using EFS. A systematic review and meta-analysis [33] using only Brazilian studies, determined a prevalence of frailty of 24%. Another study using this review methodology [34] reported that the prevalence of frailty in Latin America and the Caribbean was 19.6%, which is like the profile of the frail older adults in this study, where the frequency was 19.8%; however, this is below that determined for Brazilian studies alone [12,33]. Thus, the characteristics of the population studied in the thematic project, which this study is part of, shows that the prevalence of this condition is in line with that expected for the continent, but we know that the results can be affected due to the type of assessment used to define fragility in the population. Here we used the EFS, since it is a clinical tool that is easy to apply and, according to the literature, can be useful in making therapeutic decisions daily [35] especially in primary health care settings. However, the criteria established by Fried et al. [17] are considered the gold standard for defining frailty. We highlighted that one of the difficulties in conducting research in a primary care setting using the instruments indicated by Fried et al. [17] was the use of and, more importantly, access to a handheld dynamometer.

Using this instrument as a routine screening measure is beyond the resources and applicability of most Brazilian primary health care units. The cross-sectional study approach presents limitations regarding monitoring the possible effects of frailty and its association with the emergence of hospitalization during a follow-up of 12 prospective months, as observed in longitudinal studies. Another limitation of this study is related to data collection that is based on the self-reporting of the occurrence of certain conditions, such as diseases, use of medications, and hospitalization. Despite these limitations, the study contributes to increase to the care for the older adult population seeking primary health care. According to Jankoska-Polanska et al. [35] knowledge concerning the factors associated with frailty enables the development of health actions aimed at older adults. In addition, we know that a network of health care is essential for longitudinal monitoring of the population assisted by the SUS. The low frequency of hospitalization in this population may be an indication of longitudinal care for this population. Since there is no single national medical record coordinated the SUS that allows health care professionals to access all the patient’s clinical information and the services they use, we still need to collect this information during health team consultations with these older adults and/or their families. We also emphasize the importance of understanding the care map of older adults in relation to the use of different levels of health care, whether this is public and/or private, to ensure comprehensive care for this population. Indeed, this is an important doctrinal principle of SUS.

Conclusion

We conclude that the occurrence of hospitalization in the preceding 12 months was an outcome reported more frequently by vulnerable and frail older adults, particularly the latter, compared with non-frail older adults, even though the prevalence of hospitalization was low in all groups of participants analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the entire team of the project “Síndrome da fragilidade: Identificação e monitoramento de vulnerabilidade em idosos usuários de Unidades Básicas de Saúde no município de Santos/SP”. We would also like to thank the Santos Secretary for Municipal Health for authorizing the research, the professionals of the primary health units that participated in the study for helping us during data collection, and, especially, the older adults who agreed to participate in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Straus S, Fortin M, Guthrie B et al. (2017) Multimorbidity, dementia and health care in older people: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open 5(3): 623-631.

- Burch JB, Augustine AD, Frieden LA, Hadley E, Howcroft TK et al. (2014) Advances in geroscience: impact on healthspan and chronic disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): S1-S3.

- Fhon JRS, Rodrigues RAP, Santos JLF, Diniz MA, Dos Santos EB et al (2018) Factors associated with frailty in older adults : a longitudinal study. Rev Saude Publica 52: 74-82.

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G (2004) Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and a care. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(3): 255-263.

- Campbell AJ, Buchner DM (1997) Unstable disability and the fluctuations of frailty. Age Ageing. 26: 315–318.

- Ruiz JG, Dent E, Morley JE, Merchant RA, Beilby J, et al. (2020) Screening for and Managing the Person with Frailty in Primary Care: ICFSR Consensus Guidelines. J Nutr Health Aging 24(9): 920-927.

- Lee L, Patel T, Hillier LM, Maulkhan N, Slonim K et al. (2017) Identifying frailty in primary care: A systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17(10): 1358-1377.

- Nguyen AT, Nguyen TX, Nguyen TN, Nguyen THT, Pham T et al (2019) The impact of frailty on prolonged hospitalization and mortality in elderly inpatients in Vietnam : a comparison between the frailty phenotype and the Reported Edmonton Frail Scale. Clin Interv Aging 14: 381-388.

- Joosten E, Demuynck M, Detroyer E, Milisen K (2014) Prevalence of frailty and its ability to predict in hospital delirium, falls, and 6-month mortality in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr 14: 1.

- Shim EY, Ma SH, Hong SH, Lee YS, Paik WY et al. (2011) Correlation between frailty level and adverse health-related outcomes of community-dwelling elderly, oneyear retrospective study. Korean J Fam Me 32(4): 249-256.

- Marchiori GF, Tavares DMDS (2017) Changes in frailty conditions and phenotype components in elderly after hospitalization. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 10(25): e2905

- Reis Júnior WM, Carneiro JA, Coqueiro Rda S, Santos KT, Fernandes MH (2014) Pre-frailty and frailty of elderly residents in a municipality with a low Human Development Index. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 22(4): 654-661.

- Ministério da Saúde (2016) Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estraté Caderneta da Pessoa idosa. Brasilia (DF).

- Ministério da Saúde (2006) Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde Departamento de Atenção Bá Caderno de Atenção Básica – Envelhecimento e saúde da pessoa idosa. Brasilia (DF).

- Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K (2006) Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing 35(5): 526-529.

- Fabrício-Wehbe SCC, Schiaveto FV, Vendrusculo TRP, Haas VJ, Dantas RAS, et al. (2009) Adaptação cultural e validade da Edmonton Frail Scale – EFS em uma amostra de idosos brasileiros. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem 17(6): 1043-1049.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C et al. (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontolog Med Sci 56(3): 146-156.

- Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Linderberg S, Frieswijk N, Slates JP (2004) Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(9): 962-965.

- Pagno AR, Gross CB, Gewehr DM, Colet CF, Berlezi EM (2018) Drug therapy, potential interactions and iatrogenesis as factors related to frailty in the elderly. Rev. bras. geriatr. Gerontol 21(5): 588-596.

- Sousa RM, Santana RF, Santo FHF, Almeida JG, Alves LAF (2010) Diagnósticos de enfermagem identificados em idosos hospitalizados: associação com as síndromes geriá Esc Anna Nery 14(4): 732-741.

- Alves MKL, Oliveira NGN, Pegorari MS, Tavares DMS, Rodrigues MCS et al. (2020) Evidence of association between the use of drugs and community-dwelling older people frailty: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J 138(6): 465-474.

- Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX (2014) Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging 9: 433-441.

- Brigola AG, Alexandre TS, Inouye K, Yassuda MS, Pavarini SCI et al (2019) Limited formal education is strongly associated with lower cognitive status, functional disability and frailty status in older adults. Dement. neuropsychol 13(2): 216-224.

- Freitas FFQ, Rocha AB, Moura ACM, Soares SM (2020) Fragilidade em idosos na Atenção Primária à Saúde: uma abordagem a partir do geoprocessamento. Ciê saúde coletiva 25(11): 4439-4450.

- Life expectancy at birth, total (Years). The World Bank.

- Ye B, Gao J, Fu H (2018) Associations between lifestyle, physical and social environments and frailty among Chinese older people a multilevel analysis. BMC Geriatrics 18: 314-324.

- Aznar-Tortonda V, Palazón-Bru A, Gil-Guillén VF (2020) Using the FRAIL scale to compare pre-existing demographic lifestyle and medical risk factors between non-frail, pre-frail and frail older adults accessing primary health care: a cross-sectional study. PeerJ 8: e10380.

- Remor CB, Bós AJG, Werlang MC (2011) Características relacionadas ao perfil de fragilidade no idoso. Scientia Medica 21 (3): 107-112.

- Grden CRB, Rodrigues CRB, Cabral LPA, Reche PM, Bordin D et al. (2019) Prevalência e fatores associados à fragilidade em idosos atendidos em um ambulatório de especialidades. Rev Eletr Enferm 21: 52195.

- Stillman GR, Stillman AN, Beecher MS. (2021) Frailty is associated with early hospital readmission in older medical patients. J Appl Gerontol 40(1): 38-46.

- Freire JCG, Nóbrega IRAP, Dutra MC, Silva LM, Duarte HA (2017) Fatores associados à fragilidade em idosos hospitalizados: uma revisão integrativa. Saúde debate 41(115): 1199-1211.

- Cunha AIL, Veronese N, Borges SM, Ricci NA (2019) Frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 56: 100960.

- Melo RC, Cipolli GC, Buarque GLA, Yassuda MS, Cesari M, et al. (2020) Prevalence of frailty in Brazilian older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging 24(7): 708-716.

- Da Mata FAF, Pereira PPdS, Andrade KRCd, Figueiredo ACMG, Silva MT et al. (2016) Prevalence of frailty in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 11(8): e0160019.

- Jankowska-Polańska B, Uchmanowicz B, Kujawska-Danecka H, Nowicka-Sauer K, Chudiak A, et al. (2019) Assessment of frailty syndrome using Edmonton frailty scale in Polish elderly sample. Aging Male 22(3): 177-186.