Palliative Care for Elderly Non-Oncology Patients in an Internal Medicine Service

Elaine Aires Santos*1, Nereida Kilza da Costa Lima2 and Elga René Freire3

1Specialist in Geriatrics, Hospital das Clínicas, FMRP-USP. Master of Medicine by the Abel Salazar Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICBAS). Master of Palliative Care, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Portugal

2Associate Professor, Division of General Practice and Geriatrics, Portugal

3Hospital assistant graduated in Internal Medicine, coordinator of the In-Hospital Support Team for Palliative Care at Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto (CHUP), Portugal

Submission: December16,2020;Published: January 07, 2020

*Corresponding author: Elaine Aires Santos, Specialist in Geriatrics, Hospital das Clínicas, FMRP-USP. Master of Medicine by the Abel Salazar Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICBAS). Master of Palliative Care, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Portugal

How to cite this article: Elaine Aires S, Nereida Kilza da Costa L, Elga René F. Palliative Care for Elderly Non-Oncology Patients in an Internal Medicine Service. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2020; 6(1): 555676s. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2021.05.555676

Abstract

Objectives: To identify elderly patients with progressive and advanced chronic diseases with indication for palliative approach in a tertiary hospital, assessing their characteristics, needs, main symptoms and measuring how many of these are referred to the In-Hospital Support and Palliative Care Team (IHSTPC) and the profile of these.

Methods: Descriptive, cross-sectional, and observational study, which aimed to identify elderly patients with needs for Palliative Care of non-oncological aetiology, over a period of 3 months. Patients whose Surprise Question was positive (SQ+) were selected according to their respective attending physicians. Data were collected using the NECPAL CCOMS-ICO version 3.1 2017 tool, a questionnaire survey and the preparation of a patient registration form.

Results: There was a low identification of the need for PC by health professionals (24.5%). Of the sample of 49 elderly individuals hospitalized with positive NECPAL, IHSTPC support was requested for 9 (18%). The higher the NECPAL score of the selected sample, the greater the probability for the internist to request support from specialized PCs (p<0.001). There was an average of 27 (±17.6) days between admission to the unit and the request for support from the IHSTPC, with an average of 3 persistent symptoms per patient.

Conclusion: The use of tools is an important resource to assist in the early identification of patients with palliative needs. Its use can help to indicate the palliative approach at the right time, and to understand the needs of the patient with advanced chronic disease.

Keywords: Palliative care; Palliative Medicine; Elderly; Chronic disease; Geriatrics

Introduction

Population aging is a global reality. Intrinsic to this process is the increase in the prevalence of chronic diseases and their consequences, namely greater functional dependence, cognitive decline, excessive symptoms, polypharmacy, the need to use health services and, finally, a lower quality of life. It is estimated that, in developed countries, about 75% of the population will die due to chronic conditions, and the prevalence of patients with palliative needs is around 1.33% concerning general population and 7% of population aged ≥65 years. The prevalence reaches values between 26-40% in the population of acute hospitals, and between 60 and 70% in nursing homes [1]. This reality is associated with greater needs for palliative care (PC). The estimated number of people in need of PC at the end of their lives is 20.4 million - the largest proportion concerns adults, 94% of the cases, 69% of whom are over 60 years of age [2]. The vast majority of adults who need PC have progressive non-malignant diseases, the most common being cardiovascular ones (38.5%); cancer appears in second place (34%), followed by chronic respiratory diseases (10.3%), HIV/AIDS (5.7%) and diabetes (4.5%). It is also estimated that, on average, 37.4% of all deaths from all causes require PC, which may vary according to the region and the income of each location.

In higher income countries, with elderly populations, the percentage may exceed 60% of total mortality, while in underdeveloped countries the numbers are lower due to the higher prevalence of deaths from infectious diseases and injuries [2]. The higher prevalence of chronic diseases is accompanied by the overuse of health services and public health expenditures, which increase as the population ages. A study carried out in the United States of America showed that the elderly represented 13% of the population of this country; however, they were responsible for almost 40% of hospitalizations, with rates that tend to be more significant with advancing age [3]. Despite this knowledge, PC are still traditionally offered to people with cancer. Thus, patients with palliative needs due to chronic non-oncological progressive diseases are more likely to suffer from excessive symptoms, high psychological distress, in addition to experiencing the lack of communication and information on the part of professional teams [4]. Consequently, to better meet the needs of the aging population, it is necessary to improve and expand access to PC for people with multiple diseases and who die of cancer [5]. Studying the standard of PC reach and applicability can help to develop strategies, to minimize failures that happen and allows for greater population access to PC. Based on the above, the objective of this study was to identify elderly patients with progressive and advanced chronic diseases with indication of a palliative approach in a tertiary hospital, assessing their characteristics, needs, main symptoms, and measuring how many of these are referred to the In-Hospital Support Team and Palliative Care (IHSTPC) and their profile.

Materials and Methods

Methodology

Descriptive, cross-sectional and observational study, which aimed to identify elderly patients with PC needs due to advanced chronic diseases and with limited life prognosis, of non-oncological aetiology, over a period of 3 months. Patients whose positive surprise question was positive (SQ+) were selected according to their respective attending physicians. Then, the NECPAL CCOMSICO version 3.1 2017 [6] tool was applied, with evaluation of clinical and psychosocial parameters requested in the tool. The observation of epidemiological data, comorbidities, symptoms, length of stay and the confirmation of referral to the PC service, were carried out through a questionnaire survey. A registration form for patients who were evaluated by the hospital’s IHSTPC, in the same period, was also prepared in order to allow for data comparison and discussion.

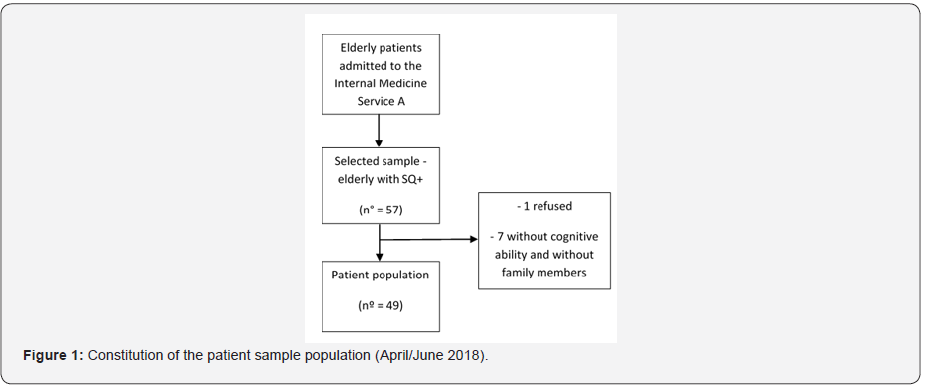

Sample

The studied sample consisted of 49 elderly patients (aged ≥65 years) admitted to Unit A of the Internal Medicine Service (MI) of Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto - CHUP (Porto University Hospital Centre), with chronic diseases and progressive causes of non-oncological aetiology, from April to June 2018. During this period, 540 patients were admitted, 426 of whom were aged 65 or over. The sample was identified randomly from the list of hospitalized patients (Figure 1). Among these patients, doctors were asked to indicate those who were in their care, aged 65 or over, with advanced chronic disease, non-oncological, and with prognosis reserved for the following year. The agreement between different doctors of the same team that took care of the patient was not necessary for a case to be selected.

The study was carried out in the wards of the IM Service (Unit A), of the CHUP, which is a public, university, tertiary and multidisciplinary hospital. According to data from the Portuguese National Health System (SNS), the number of beds in charge of MI in 2015 was 4653, in a total of 16294 in SNS hospitals, which corresponds to 29% of the hospitalization capacity in these hospitals. At CHUP, the measured number of hospitalizations in 1 month is 4304 patients, which represents an occupancy rate of 100.5% of the beds, with an average delay of 10.6 days per patient [7]. Specifically, in the Medicine A service, where data were collected from this study and which has 49 beds, data in the annual hospital report indicate that 1561 patients were hospitalized, with an average delay of 9.4 days.

Data Collection Tools

NECPAL CCOMS-ICO instrument©: The NECPAL CCOMS-ICO version 3.1 2017 tool was used as a strategy to identify patients with advanced chronic illnesses who need palliative measures. This tool is enabled for use by professionals who speak English or Spanish, and for this study it has been translated into Portuguese. The tool is divided into the following categories: 1. “Surprise Question” (SQ); 2. Choice/demand or need for PC approach; 3. General clinical indicators of severity and progression, including comorbidities and resource use; and 4. Specific disease indicators. The patient was categorized as SQ+ when the doctor’s response was “no” (i.e., “I would not be surprised if that patient died in the next 12 months”). NECPAL+ patients were defined as those with at least one more positive category or parameter in addition to SQ, which could vary from NECPAL 1+to13+. The measurement of these parameters is made resorting to internationally recognized measures or scales indicated on the NECPAL instrument itself, the main ones being Karnofsky scales [8], Barthel [9], Mini-mental [10], Detection of Emotional Malaise (DME) [11] and Edmonton [12], in addition to other specific indicators indicated in the tool. The answers to the variables of the categories of the NECPAL tool were acquired through interviews with doctors, patients or, if necessary and possible, with family members. The information available in the patient’s clinical records could also be retrieved by the principal investigator. All NECPAL+ patients were considered in need of a palliative approach.

Elaboration of a questionnaire survey to patients: A complementary semi-structured questionnaire was designed to collect additional information from patients. This was divided into the categories:

1. Identification (gender, age, length of stay, if there was a request to the IHSTPC and how long after admission)

2. Identification of the disease or condition that led to hospitalization

3. Comorbidities, which were completed according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [13]

4. Symptoms present at the time of assessment, based on symptoms frequently reported in the literature, associated with patients with palliative needs [14,15].

For the application of this instrument, if the patient had physical and cognitive conditions to be questioned, data were collected directly with the patient. Otherwise, an attempt was made to identify a family member or visitor who was able to answer the questions. Regarding the records of the total number of requests for IHSTPC support at the hospital, data were collected between April and June 2018.

Data Processing

A database was built using software IBM SPSS (version 25), for statistical treatment through the frequency analysis of data collected through NECPAL CCOMS-ICO version 3.1 2017, questionnaire surveys applied to health patients and patient registration data assessed by the IHSTPC from April to June 2018. The evaluation of the association and correlation between some variables was also performed, using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Pearson test (when variables had parametric distribution).

Ethical Considerations

This research was approved by the CHUP Ethics Committee for Health (N/REF.2017.193 (166-DEFI/158-CES). The research includes only individuals who voluntarily consented to participate in the study, after being provided with the informed consent form, and the information document on the study. The research was carried out only with the collection of secondary data, which were used only for what referred in its objectives, with the information being presented in a confidential, collective manner and without any prejudice to the individuals involved. Data are under the custody of the principal researcher, and their secrecy and confidentiality are guaranteed.

Results

Assessment of patients

The total of respondents corresponded to a sample of 49 individuals, with an average age of 84 (±6.6) years, hospitalized, on average, 16 days before the assessment. The main conditions or diseases motivating the hospitalization of each patient were evaluated. The main disease that motivated hospitalization and the severity of the selected patients was congestive heart failure (CHF) (57.1%), followed by infectious conditions, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection or pseudomembranous colitis (40.8%), as well as diagnosis of dementia (26.5%). It is important to report that many patients showed more than one condition or illness as a cause of hospitalization, hence 81 diseases were obtained. The most common associations were between dementia + infectious disease (N=7), CHF + infectious disease (N=6), CHF + dementia (N=4) and CHF + social vulnerability (N=3). There were 3 diseases not diagnosed as candidates to admission concerning any of the patients, namely Parkinson’s disease, stroke and AIDS, probably because the most serious cases of these situations are admitted directly to specialized neurology and infectious disease units, for example.

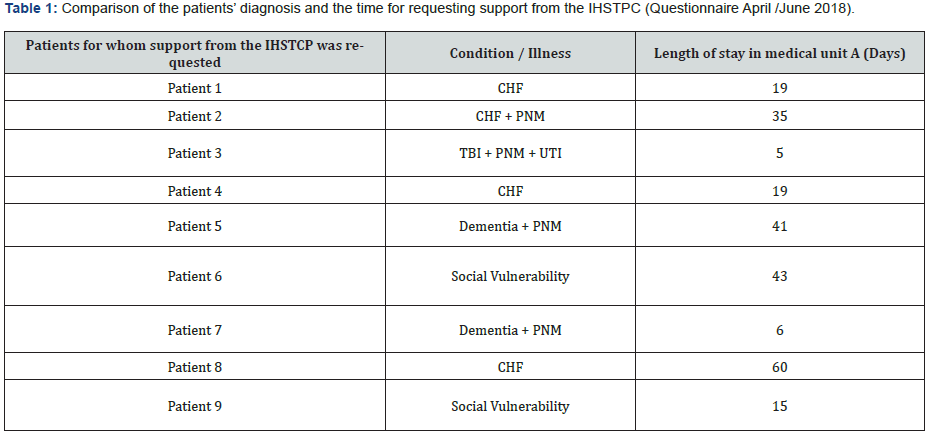

Regarding the support requested from the IHSTPC, it occurred in only 9 patients, which represents about 18% of the total patients evaluated. The time requested in the shortest time was 5 days, while the maximum was 60 days, with an average of 27 (±17.6) days between admission to the unit and the request for support from the IHSTPC. The diagnosis that most frequently motivated the request for specialized support was CHF, followed by pneumonia (PNM), dementia and social vulnerability, with the majority having at least 2 of these diagnoses combined. The diagnosis by patients and the length of stay in the Medical Unit A at the time of the request for support to the IHSTPC are shown in (Table 1).

Legend: CHF – Congestive Heart Failure; PNM – Pneumonia; UTI – Urinary Tract Infection.

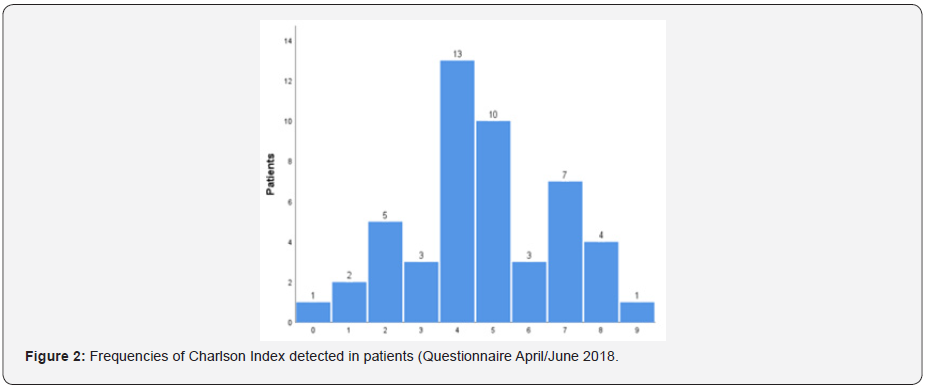

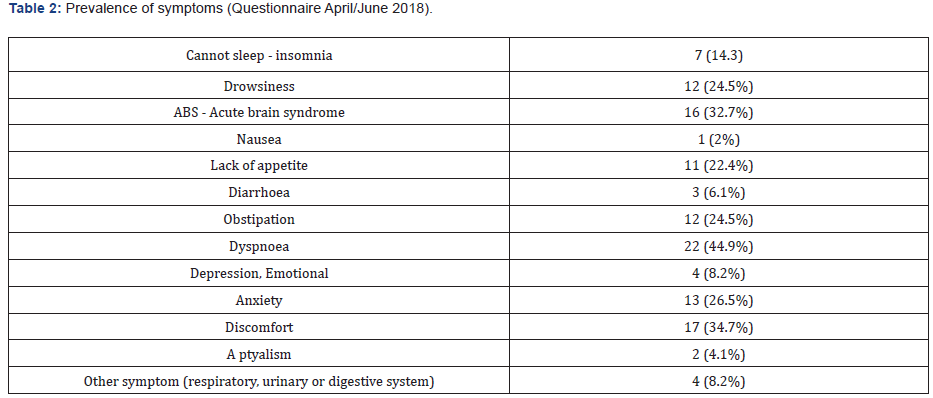

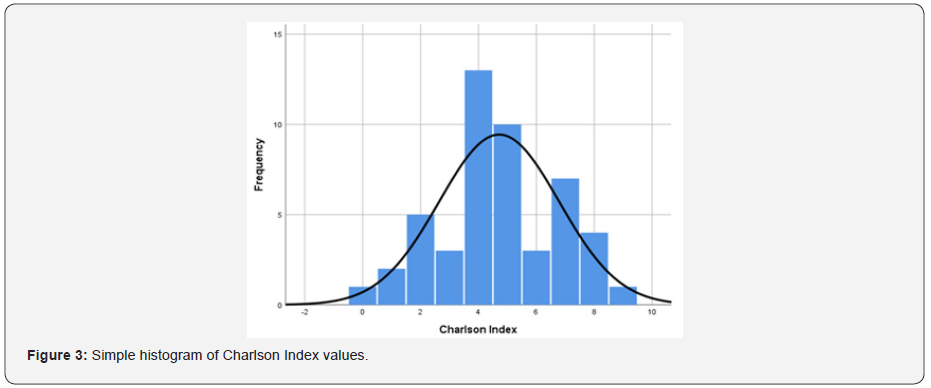

The most frequent comorbidity among patients was CHF, followed by nephropathy, chronic pneumopathy, dementia, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vasculopathy and cerebrovascular disease. The minimum number of comorbidities was no comorbidity in 1 patient, while the maximum was 9 also in 1 patient. The result of the CCI score, according to the quantity and type of the disease, can be seen in (Figure 2), where the most frequent value was 4, which represents a mortality rate of 52% in 1 year. The most prevalent symptom among the patients evaluated was dyspnoea, present in 44.9% of patients. Other common symptoms were malaise, confusion/delirium, tiredness, anxiety, drowsiness, constipation, poor appetite, pain, and insomnia (Table 2). There was an average of 3 symptoms per patient, which explains the reason why the prevalence of symptoms exceeded the number of patients.

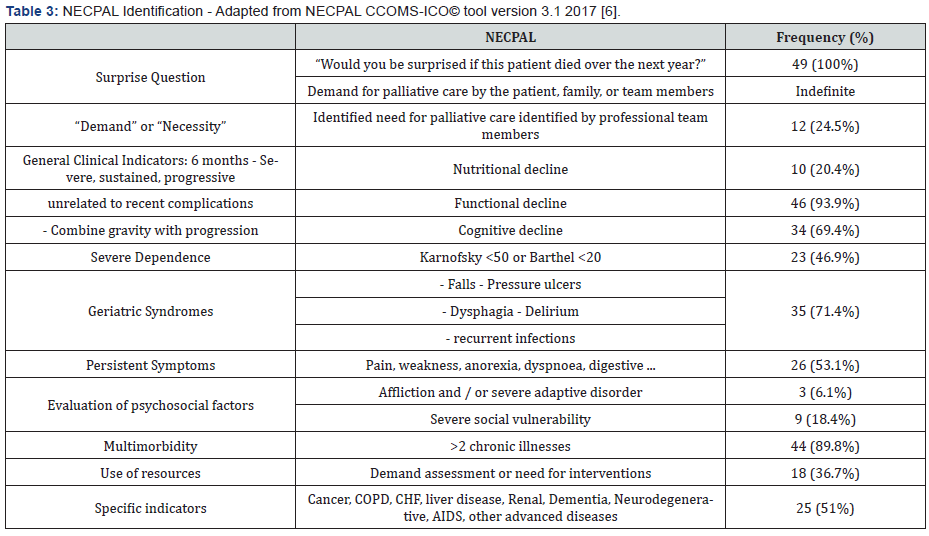

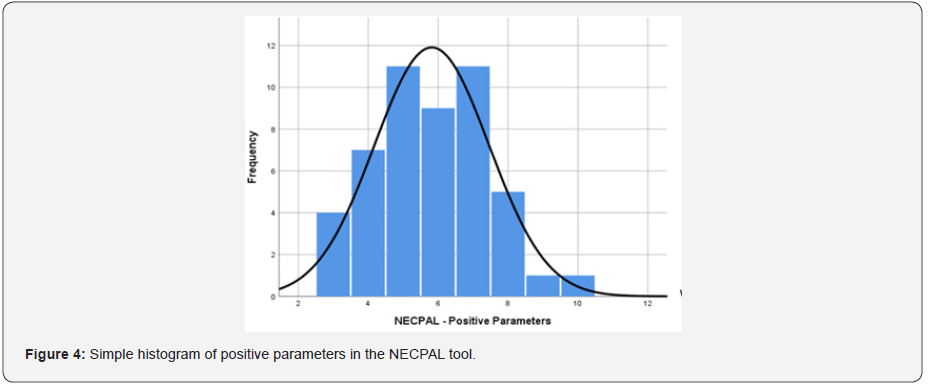

The next step in the research was the application of the NECPAL instrument (Table 3). shows the frequencies in number and percentage of each parameter of the evaluated tool. All users for whom the SQ was positive also had a positive NECPAL; the most frequently positive parameters were functional decline (93.9%), multimorbidity (93.8%), geriatric syndromes (71.4%), cognitive decline (69.4%), persistent symptoms (53.1%) and specific indicators of advanced diseases (51%).

There was a low identification of the need for PC by health professionals (24.5%). This identification was accounted for when the professionals expressed verbally, based on data from the patients’ clinical records or when support was requested from the IHSTPC (Figures 3 & 4).

IHSTPC records

The total number of requests for support to the IHSTPC was 30, of which 76.7% were individuals aged ≥65 years, while only 23.3% were younger. The minimum age was 49 years, and the maximum was 95 years, making an average age of 76.1 ± years of age/sick for individuals whose support from the specialized team was requested. In relation to the total of 23 individuals aged ≥65 years, 47.8% were female, while 52.2% were male. Three types of underlying diseases were identified for elderly patients in this sample: cancer (52.2%), cardiovascular (30.4%) and neurological (17.4%).

Discussion

In medical practice the group of patients with palliative needs is predominantly elderly and the most common clinical conditions are advanced frailty, dementia, and organ failure, in addition to cancer [16]. In the present study similar data were found since elderly patients with palliative needs, with a mean age of 84 years, suffered from the main causes of hospitalization: CHF, followed by dementia, conditions related to fragility, respiratory diseases, or other organic failures. The increase in population survival, associated with the great overload of symptoms that these diseases can cause, leads to a substantial increase in the number of people with PC needs. Defining the need for PC for users with non-cancer diseases is not a simple task. Diseases due to organ failure are accompanied by several factors that influence its evolution, such as the varied aetiology, the presence of other comorbidities and the gradual decline punctuated by episodes of exacerbation, which may vary in each case [17].

In the present study, all patients identified as SQ+ had a NECPAL+. These data are equivalent to the results of the study carried out by Gómez-Batiste et al [16] which identified 55 patients admitted to a general and university hospital for progressive chronic diseases over 1 year, with 52 having SQ+ and 51 having NECPAL+.

There is a greater request for support to the IHSTPC in cases presenting higher scores from the NECPAL tool, probably because those are patients with higher parameters of severity and dependence. In the records of requests for support to the IHSTPC within the study period, the average age was 76.1 (±6.8) years, which reinforces the elderly majority of the population with needs in PC.

It is known that the geriatric population is associated with a worse prognosis and greater probabilities of rehospitalization. Other characteristics associated with this outcome are cognitive impairment, institutionalized living, heart, or kidney failure. Respiratory and urinary tract infections and exacerbation of CHF were the main diagnoses found in patients readmitted within a 3-month period [18]. In the present study these diagnoses cited were also the main ones found in patients requiring support from the IHSTPC. In addition, social vulnerability, with regard to the lack of social and family support, was present in 2 of the 9 patients referred to PC, which draws attention to the role of this specialty not only from a physical and psychological point of view, but also socially, and, moreover, spiritually.

An association was observed between the number of comorbidities and a higher score of the NECPAL tool. In fact, there was a high prevalence of multimorbidity among the evaluated users, and the vast majority (93.8%) had more than 2 associated comorbidities, indicating a low probability of 1-year survival in the evaluated patients. In addition, it was observed that 25 patients (51%) met NECPAL criteria for severity/progression/ advanced disease, indicating that this is a population with important severity and poor prognosis.

Of the 423 elderly people aged 65 or over, admitted in a 3-month period, 57 were identified with a limited life prognosis, according to the SQ, which represents only 13.5% of the total. It is believed that, in this case, there is an underestimation of the number of patients who can benefit from PC, as in a study carried out in this same IM Service, in 2009, it was identified that 22.9% of hospitalized patients had a disease chronic, understood as advanced; of these, it was observed that almost 75% had noncancer disease [19].

Despite the clear evidence of the advantages of involving specialized PC services in caring for people with various lifelimiting illnesses, those who can benefit from these services do not always use them [20]. As noted in the IHSTPC records between April and June 2018, 53% of the patients evaluated were oncological. These results, despite the higher percentage of cancer patients, have a higher rate of non-cancer patients than most studies. A large survey carried out in Belgium, in 2015, showed that 34% of individuals with organ failure had specialized PC, 48% with dementia and 73% having died of cancer [20]. In another study conducted in Scotland, 60% of patients who died of cancer were evaluated by PC, while only 20% of patients who died of other conditions such as CHF, dementia, and COPD, were evaluated [21].

There is also a wide variation in time periods from admission to the request for IHSTPC collaboration: between 5 to 60 days (average of 27 days). In a survey [22] carried out in 11 Portuguese PC inpatient units, published in 2012, it was observed that there is a delay in referring patients to PC services, usually in the last stage of life; in this study, patients admitted to a PC unit, oncological and non-oncological, had a median survival of 11 days, with 54.41% of patients dying in the first 14 days of hospitalization, and 3.83% having passed away on the same day of admission and 4.60% one day after admission.

The quantification of days for referral to specialized PC does not necessarily indicate that a patient does not receive adequate care by the IM team, according to the patient need. However, a strong indicator that specialized help may be needed is the number of persistent symptoms counted in each patient, as PC specialists may have more experience in managing refractory and persistent symptoms. Symptom overload was found, as 53.1% of patients have persistent symptoms. In fact, on average, there are 3 symptoms per patient. Nevertheless, the need for PC was registered in 24.5% of the cases, and for 18% of the total support was requested from the IHSTPC. Thus, there is a tendency to underestimate patients’ palliative needs.

There was little referencing or requests for support from specialized PC (18%). However, professionals from the Medical Service expressed the need for palliative care for NECPAL + patients, in 12 cases (24.5%). We can suggest that the fact that they were questioned with the SQ allowed professionals to at least think about this issue, justifying a percentage slightly higher than that of previous referrals.

There is no precise justification for this low referral rate, which can be interpreted in different ways. There is evidence that there is no clear transition to PC for patients with chronic diseases, but rather a slow period of decline, in which both curative care and palliative approach are needed [23]. In this way, the identification of palliative needs and the moment for transition to PC is accompanied by many doubts and uncertainties. Difficulties in recognizing the need for a palliative approach to non-cancer patients are explained by several barriers that limit or delay this indication, namely, the lack of knowledge about the meaning of PC by both health professionals and the population in general, the unpredictability of non-cancer disease, scarcity of criteria for indication of PC, failures in communication between professionals, patients and family members, limited resources for access or provision of PC by services, unfavorable socio-economic situation, beliefs and taboos regarding death [20,24-32].

These barriers can be tackled by identifying the wishes and needs of the patient with severe and progressive illness, which requires not only knowledge, but also time, patience, and practice of communication skills, which is not always developed over time by health professionals. In addition, in order to reach a greater number of users who benefit from PC, it is necessary that national or regional chronic care programs incorporate this approach as one of the elements of a global policy [16].

For a palliative approach to be carried out properly, it is essential to remember that PC should not be started in an outdated context of “giving up the patient” or “when there is nothing else to do”. In an individualized way and according to the needs of each case, this care must be initiated, including the times when there is still a chance of improvement or even reversion of the clinical condition, as active management of the disease and palliative treatment are complementary. This is so because many chronically ill elderly people have ambiguous medical prognoses, showing they may be sick enough to die, but they can also live for many years, suffering long periods of illness or disability [33]. To aid in the identification of patients with palliative needs, a number of general and specific factors for many diseases have been identified as significantly associated with survival and can assist professionals in the appropriate time for the palliative approach [34]. Thus, tools have been developed, which use parameters such as clinical judgment, decline indicators, laboratory parameters and/or prognosis estimation, in order to identify patients with palliative needs early [34-37]. We can mention some of the main examples, in recent years: The Gold Standards Framework (GSF) and its tool Prognostic Indicator Guidance (PIG), which served as inspiration for other tools such as the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators (SPICT) and Palliative Necessities (NECPAL) CCOMS-ICO, considered tools that combine different and important indicators such as the surprise question, the perception of health professionals and the preferences and desires of patients, as well as clinical parameters (progressive functional and nutritional decline, presence of comorbidities, presence of geriatric conditions and use of health resources) that contribute to identify the status specific conditions (cardiac, respiratory or other) [38].

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that there is still a low rate of identification of specialized PC needs. When support for a PC team happens, it is often late, or when there is an excess of symptoms and functional dependence. Tools, such as NECPAL, are important resources to assist in the early identification of patients, presenting advanced chronic diseases of various aetiologies, with palliative needs. Its use can help to indicate the palliative approach at the right time and to understand the needs of the patient with advanced chronic disease. However, it is important to consider that, despite efforts, there is still no absolute consensus as to when the palliative trajectory begins and, in addition, the early integration of PCs in clinical practice still depends on overcoming the numerous barriers related to the disease, with health professionals and the organization of services. Thus, more studies are still necessary to clarify the best strategies for early identification of the need for PC, especially in non-cancer disease.

Elderly “surviving” patients with long-term illnesses, symptom overload and excess of multimorbidity are increasingly common in medical practice. This fact is corroborated by the increasing number of complex elderly patients using health services. Therefore, professionals must be up-to-date and confident regarding the palliative approach of patients, and this is only possible with adequate levels of training and education on the subject. Understanding and promoting the proper introduction of palliative care, which in many cases is complementary to curative treatment, allows for better management, symptom control and promotion of quality of life for patients with palliative needs.

Author Contribution

Elaine Aires dos Santos designed and conducted the questionnaires, performed the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Elga René Freire collaborated in study design, data collection and together with Nereida Kilza da Costa Lima provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez Muñoz M, Blay C, Amblàs J, Vila L, et al. (2013) Identifying patients with chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: development of the NECPAL tool and preliminary prevalence rates in Catalonia. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 3(3): 300-308.

- Alliance WPC (2020) WHO. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. 2nd Edition ed. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance.

- Wier L, Pfuntner A, Steiner C (2006) Hospital Utilization among Oldest Adults, 2008: Statistical Brief #103. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US)

- Addington Hall J, Fakhoury W, McCarthy M (1998) Specialist palliative care in nonmalignant disease. Palliat Med.12(6):417-427.

- WHO (2011) Palliative care for older people: better practices. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe

- Gómez-Batiste X, Amblàs J, Costa X, Espaulella J, Lasmarías C, Ela S, et al. Recomendaciones para la atención integral e integrada de personas con enfermedades o condiciones crónicas avanzadas y pronóstico de vida limitado en Servicios de Salud y Sociales: NECPAL-CCOMS-ICO© 3.1; 2017.

- Carvalho A, Dias C, Morais A, Veríssimo MT, Sousa MC-B, et al. (2016) Rede de Referenciação Hospitalar - Medicina Interna. Lisboa: República Portuguesa - Saúde

- Mor V, Laliberte L, Morris JN, Wiemann M (1984) The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale. An examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer.53(9): 2002-2027.

- Mahoney FI, (1965) Barthel DW FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J. 14:61-65.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 12(3):189-198.

- Limonero JT, Mateo D, Maté-Méndez J, González-Barboteo J, Bayés R, Bernaus M, et al. (2012) [Assessment of the psychometric properties of the Detection of Emotional Distress Scale in cancer patients]. Gac Sanit. 26(2):145-152.

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K (1991) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 7(2):6-9.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 40(5):373-383.

- Stiel S, Matthies DM, Seuß D, Walsh D, Lindena G (2014) Symptoms and problem clusters in cancer and non-cancer patients in specialized palliative care-is there a difference? J Pain Symptom Manage. 48(1): 26-35.

- Chino FT (2012) Plano de Cuidados: cuidados com o paciente e a família. In: Carvalho RT, Parsons HA, editors. Manual de Cuidados Paliativos ANCP. São Paulo: Academia Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos p. 392-399.

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez-Muñoz M, Blay C, Amblàs J, Vila L, et al. (2014) Prevalence and characteristics of patients with advanced chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 28(4):302-311.

- Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, Rutten FH, McDonagh T, et al. (2009) Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 11(5): 433-443.

- Ben-Chetrit E, Chen-Shuali C, Zimran E, Munter G, Nesher G A (2012) simplified scoring tool for prediction of readmission in elderly patients hospitalized in internal medicine departments. Isr Med Assoc J 14(12):752-756.

- Rui C, Elisabete S, Tiago G, Nelson R [2009] Qualidade e Satisfação com a Prestação de Cuidados na Patologia Avançada em Medicina Interna. Arq Med 23(3): 95-101.

- Beernaert K, Deliens L, Pardon K, Van den Block L, Devroey D, et al. (2015) What Are Physicians' Reasons for Not Referring People with Life-Limiting Illnesses to Specialist Palliative Care Services? A Nationwide Survey. PLoS One. 10(9): e0137251.

- Harrison N, Cavers D, Campbell C, Murray SA (2012) Are UK primary care teams formally identifying patients for palliative care before they die? Br J Gen Pract. 62(598): e344-352.

- Dias AS (2012) Referenciação para unidades de internamento de cuidados paliativos portuguesas: Quando? Quem? E Porquê? Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisboa;

- Crawford GB, Brooksbank MA, Brown M, Burgess TA, Young M (2013) Unmet needs of people with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recommendations for change in Australia. Intern Med J. 43(2):183-190.

- Beernaert K, Cohen J, Deliens L, Devroey D, Vanthomme K, et al. (2013) Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: a population-based study. Respir Med. 107(11):1731-1739.

- O'Leary N, Tiernan E (2008) Survey of specialist palliative care services for noncancer patients in Ireland and perceived barriers. Palliat Med. 22(1):77-83.

- Ouchi K, Wu M, Medairos R, Grudzen CR, Balsells H, et al. (2014) Initiating palliative care consults for advanced dementia patients in the emergency department. J Palliat Med. 17(3):346-350.

- Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, Dev S, Biddle AK, et al. (2014) "Not the 'grim reaper service'": an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 3(1): e000544.

- Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Hazeldine C, et al. (2007) Improving end-of-life care for patients with chronic heart failure: "Let's hope it'll get better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won't". Heart. 93(8): 963-967.

- Torke AM, Holtz LR, Hui S, Castelluccio P, Connor S, Eaton MA, et al. (2010) Palliative care for patients with dementia: a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(11): 2114-2121.

- Green E, Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C (2011) Exploring the extent of communication surrounding transitions to palliative care in heart failure: the perspectives of health care professionals. J Palliat Care 27(2):107-116.

- Mc Carty CE, Volicer L (2009) Hospice access for individuals with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 24(6): 476-485.

- Rush B, Hertz P, Bond A, McDermid RC, Celi LA (2017) Use of Palliative Care in Patients with End-Stage COPD and Receiving Home Oxygen: National Trends and Barriers to Care in the United States. Chest 151(1): 41-46.

- Lynn J, Adamson DM (2003) Living Well at the End of Life - Adapting Health Care to Serious Chronic Illness in Old Age. Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation.

- Duenk RG, Heijdra Y, Verhagen SC, Dekhuijzen RP, Vissers KC, (2014) Prolong: a cluster-controlled trial to examine identification of patients with COPD with poor prognosis and implementation of proactive palliative care. BMC Pulm Med. 14:54.

- Thoonsen B, Engels Y, van Rijswijk E, Verhagen S, van Weel C, et al. (2012) Early identification of palliative care patients in general practice: development of RADboud indicators for PAlliative Care Needs (RADPAC). Br J Gen Pract. 62(602): e625-631.

- O'Callaghan A, Laking G, Frey R, Robinson J, Gott M (2014) Can we predict which hospitalized patients are in their last year of life? A prospective cross-sectional study of the Gold Standards Framework Prognostic Indicator Guidance as a screening tool in the acute hospital setting. Palliat Med. 28(8):1046-1052.

- Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Adhikari NK (2017) The "surprise question" for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cmaj. 189(13): E484-e493.

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez-Muñoz M, Blay C, Espinosa J, Contel JC, (2012) Identifying needs and improving palliative care of chronically ill patients: a community-oriented, population-based, public-health approach. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 6(3):371-378.