Bi-direction Coding for Qualitative Analysis Surfaced the Importance of Social Connectedness as a Coping Mechanism in Retirement Transition

Amberyce Ang*

University of Social Sciences, Singapore

Submission: October 13, 2020;Published: November 06, 2020

*Corresponding author: Amberyce Ang, PhD candidate, University of Social Sciences, Singaporea

How to cite this article: Amberyce A. Bi-direction Coding for Qualitative Analysis Surfaced the Importance of Social Connectedness as a Coping Mechanism in Retirement Transition. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2020; 5(5): 555674. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2020.05.555674

Abstract

This qualitative study aimed to understand the retirement adjustment process of retirees, factors that facilitated their successful retirement transition, and the possible effects of voluntary and involuntary retirement transition types. Using interview responses from 103 retirees, bi-directional analytical strategy was designed and applied to this study. Bi-directional analysis combines inductive and deductive coding into a two-way analysis in order to increase the validity of the findings. Using bi-directional coding and analysis, social connectedness was found to be a key coping mechanism for retirement transition, for both voluntary and involuntary retirement types. The findings suggest the importance of socio-emotional resources in retirement adjustment and recommend for more deliberate national effort to increase community engagement towards this end. On the research front, this study recommends for larger scale qualitative studies to evaluate the reliability of bi-directional coding and analysis.

Introduction

Retirement studies [1-3] found that retirement is not a uniform experience and many older workers struggle in adjusting to retirement. Pinquart & Schindler posit that resource-rich individuals were less likely to experience retirement-related change in satisfaction. Other studies [4,5] found that people with poor physical and financial resources were more likely to experience adjustment problems in retirement, resulting in lower levels of psychological well-being in retirement [6].A Swedish study [7] concurred that the retirement experience is diverse. In their examination of retirees’ six resource domains: self-esteem (emotional), autonomy (motivational), social support (social), self-rated physical health (physical), self-rated cognitive ability (cognitive) and financial resources (finances), the results showed that the retirement transition type and individual differences in resource capability had varying impact on changes in post-retirement life satisfaction. In addition to resources, the same study also noted that retirement transition type had influenced life satisfaction of retirees. Abrupt retirement had more impact on variability in life satisfaction changes than gradual retirement. Gradual retirement eased the retirement adjustment process and differences in individual resources might account for within and between person differences in well-being during the retirement adjustment process [7,8]. Assuming that gradual retirement leads to more successive lifestyle changes [9-12] then gradual retirement could potentially be associated with fewer changes in life satisfaction than those observed in abrupt retirement.

The relationship between retirement transition types and life satisfaction, and the association between resources and retirement adjustment are in conclusive and need to be further examined. Hansson et al. did not find any significant changes in post-retirement life satisfaction for either profiles of retirees with abrupt retirement or gradual retirement. Instead, the study found that social support, physical health and financial resources, were associated with overall increases in life satisfaction, while individuals lacking in these resources experienced decreased life satisfaction. In addition, individuals with less resources were more affected in abrupt retirement than in gradual retirement. This is perhaps explained by the assumption that an individual becomes more vulnerable to lifestyle changes in an abrupt retirement if he had less resources to cope with retirement transition changes [10,11,13].

In comparison to abrupt and gradual retirement transition types, other studies examined the relationship between voluntary and involuntary retirement with retirement satisfaction. An earlier study [14] found that voluntary retirement led to more positive attitudes towards retirement and higher retirement satisfaction than involuntary retirement. However, the same study also revealed health status and preretirement expectations to be even more significant predictors of retirement satisfaction than the effect of retirement transition type on satisfaction. Overall, the differences and diversity of findings from retirement studies reflected the multidimensional and dynamic process of retirement [9,15]. This study had chosen to focus on retirement adjustment and aimed to understand the retirement process of retirees, factors that facilitated their successful retirement transition, and the possible effects of voluntary and involuntary retirement transition types.

The transition from work to retirement is often regarded as a major life process which most adults have to undergo. This transition or retirement adjustment is defined [16] as “the process of getting used to life changes resulting from retirement”. As an operational construct [17], retirement adjustment was measured in terms of cognitive and self-evaluated life satisfaction [18], quality of life in terms of various personal domains such as control, autonomy, pleasure and fulfilment [19]; and retirement satisfaction. For Wang et al., retirement adjustment largely premised on resources availability. Wang’s dynamic resourcebased perspective, retirement adjustment was described as a process in which resource availability influence how retirees feel comfortable with retirement. This perspective posits that increasing resource leads to higher ability of adjustment, and decreasing resources leads to lower ability of adjustment. Stemming from this perspective and Wang et al.’s definition of retirement adjustment, this study aimed to understand the retirement transition process of retirees, compare the experiences of retirees who had undergone voluntary retirement with those who had undergone involuntary retirement and the resources that enabled retirees to adjust into retirement. For the purposes of this study retirement was considered as “voluntary” if the individual had made the choice to fully cease career employment or was ready and willing to fully withdraw from formal career employment even if the choice was absent. Conversely, retirement was considered “involuntary” if the choice for the individual to continue career employment in any form was absent.

Methods

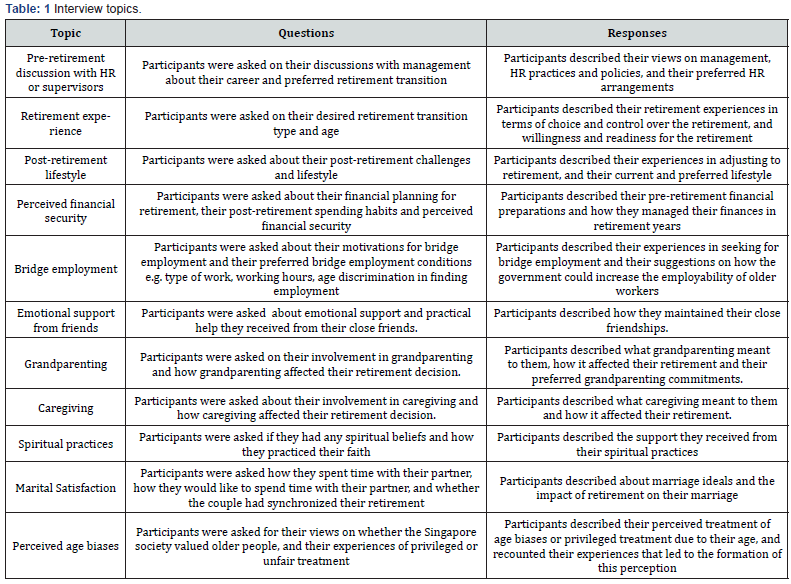

Qualitative interviews were conducted and insights from the myriad of retirement experiences were captured through the interviews. Coding and thematic analysis [20,21] were used to interpret the experiences shared through the interviews. Indepth interviews each lasting between an hour to 1 to 1.5 hours with guided questions were conducted. The topics of discussion in the guided interview are tabulated in (Table 1).

Data Collection

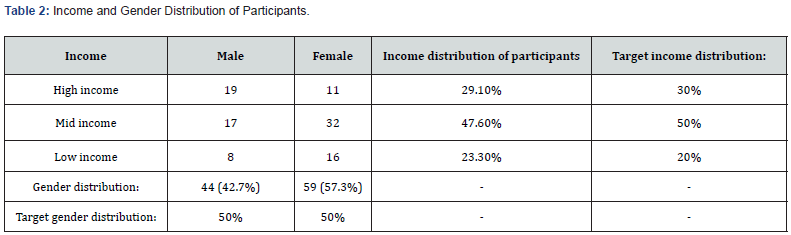

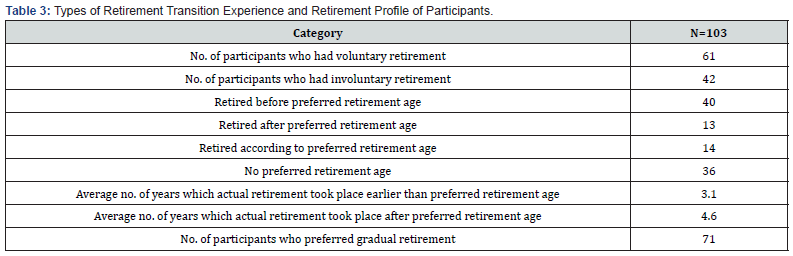

In this study “retirees” were defined as Singaporeans who were previously employed on a part-time or on a full-time basis. The age range of the subject was between 60 to 72 years, and who were previously employed on a part-time or on full-time basis. The initial participants were recruited with the support from Singapore’s grassroots associations; the Southeast Community Development Council (CDC) and Southwest CDC. Snowball sampling was then applied to ensure representativeness of the sample group. A total of 103 participants were recruited and completed the interviews (Tables 2 & 3).

Qualitative Data Analytic Strategy

Using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) [22], in-depth interviews each lasting between an hour to an hour and a half with guided questions were conducted. In applying the IPA, this study used a ground-up approach to uncover meanings and find themes [23] through the analysis of the language used by participants [24]. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Choice of words used, repeated core concepts and repeated themes were tracked. Beginning with priori coding, a list of preset codes, such as “stress”, “part-time”, “time for myself”, was drafted. At the open-coding stage, emergent codes were identified in the notes and combined with the earlier list of pre-set codes. Relationships were then identified among the open codes at the axial coding stage. Transcripts were further analysed to identify selective codes that related to the core variables of this study and identify themes. Qualitative data analysis software NVivo12 (QSR International Pte Ltd.) was used to tally analysis results with those from manual coding. Hierarchical coding trees were used to categorize the data for qualitative data analysis.

Ensuring Validity by using Bi-directional Coding Analytical Strategy

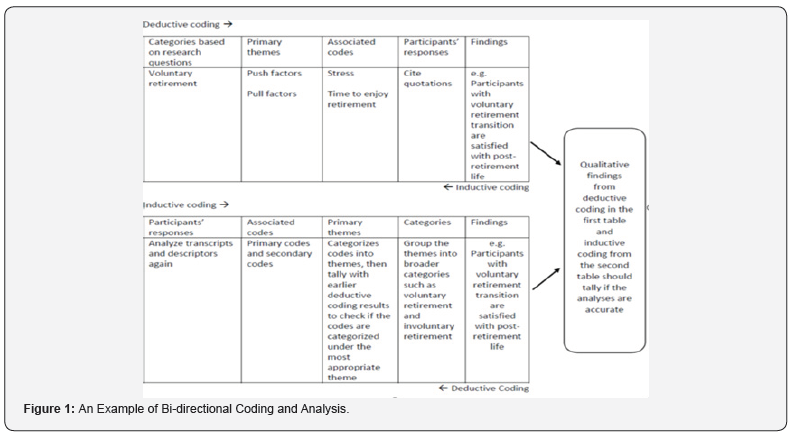

Deductive coding method [25] was first used on the qualitative data analysis of the interview transcripts. Based on the research questions, information was grouped into four main categories. Following which, the emerging themes were identified and clustered under the four categories. Words and phrases from the interview responses that support the themes were further grouped under the relevant themes. Deductive coding was first used. Thereafter, inductive coding was used to verify the analysis stemming from deductive coding. For inductive coding method, the transcripts were analyzed, and words or phrases were identified, grouped into relevant themes, and then further fitted into categories that answer the research questions. (Figure 1).

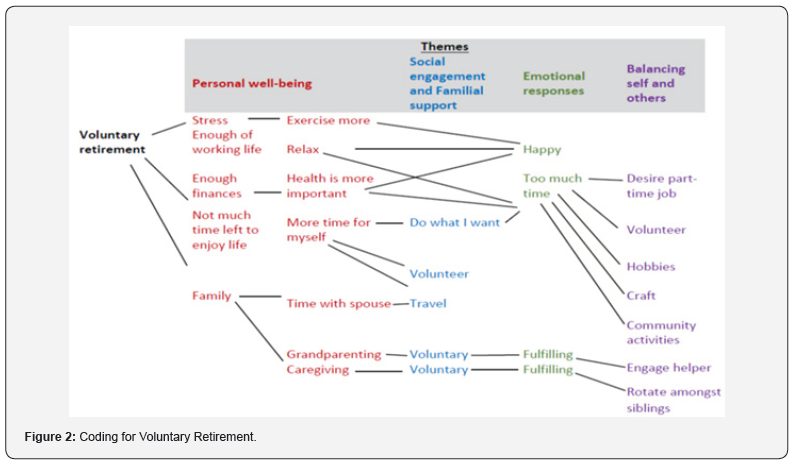

Following the critical analytical approach [26] for verification, the study sought concrete and detailed descriptions from participants. Phenomenological reduction was maintained throughout the analysis. Positive descriptors were clustered together and regrouped under themes – personal wellbeing, emotional responses, social engagement and familial support, and balancing self and others. The transcripts were then reviewed again, and the analysis was verified using backward analysis, from the core to the surface layer. Beginning by reviewing the codes under every theme to assess how well they fit into the themes. As life satisfaction and retirement satisfaction were measured with scores and analysed quantitatively, the third cluster of codes “successful transition into retirement” was to identify and understand the determinants for the successful transition. The strength of the determinants and the level of satisfaction were measured quantitatively. In (Figure 2), the codes uncovered the reasons behind voluntary retirement, which then reflected that participants with voluntary retirement, had prioritized self, prioritized family and a crucial balance between self and family as keys behind their motivation to retire and lead more fulfilling retirement lives. These codes signaled that participants had viewed retirement as an opportunity to rebalance their priorities, such as a shift from work as a priority to family as a higher priority. Coded words had also captured emotional responses which suggested that voluntary retirement had also resulted in neutral or negative emotions such as boredom and having “too much time”, hence a need to re-balance between self and other priorities again. Codes listed under “balancing self and others” uncovered coping mechanisms for the loss of work identity and “too much time” (Figure 3).

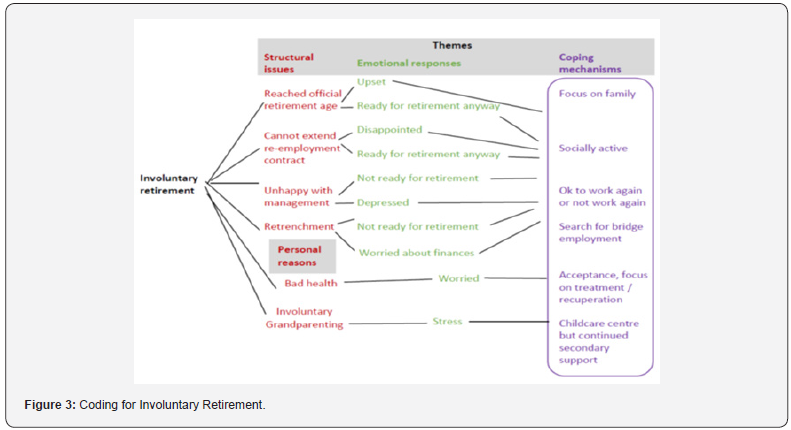

Coding for Involuntary Retirement

In (Figure 3), the codes uncovered factors that resulted in involuntary retirement, which were mainly driven by either organizational factors or personal reasons. Similarly, coded words suggested coping mechanisms for involuntary retirement. These coping mechanisms were then compared with the coping mechanisms for those who had retired voluntarily and discussed under findings. With reference to (Figure 3), the codes uncovered factors that resulted in involuntary retirement, which were mainly driven by either organizational factors or personal reasons. Similarly, coded words suggested coping mechanisms for involuntary retirement. These coping mechanisms were then compared with the coping mechanisms for those who had retired voluntarily and discussed under findings. In examining the coping mechanisms for both types of retirement, the study focused on how participants can successfully transit into retirement despite the differences in the starting point (voluntary or involuntary retirement). Coded words then reflected attitudes, perceptions, and preoccupations of participants.

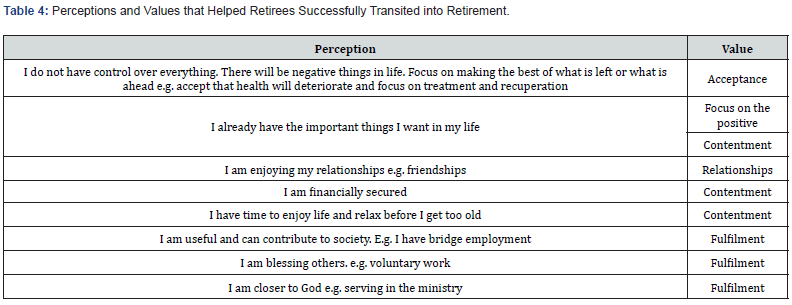

The study analyzed the attitudes, perceptions, and preoccupations of participants to understand how they helped participants transit into retirement. The varying degrees of effectiveness of these attitudes, perceptions and preoccupations were then assessed using quantitative measures. Using Pickens’ (2005) definition, “attitude is a mindset or a tendency to act in a particular way due to both an individual’s experience and temperament. Attitudes help us define how we see situations, as well as define how we behave toward the situation or object”. Perception on the other hand, refers to “the interpretation of a stimuli into something meaningful to him or her based on prior experiences. However, what an individual interprets or perceives may be substantially different from reality” [27]. With reference to (Figure 4), the codes uncovered the attitudes and perceptions behind the retirees’ preoccupations, which helps the study understand that it is not the preoccupation nor the activity itself that determines successful transition into retirement, but attitudes and perceptions are important in giving meaning and fulfilment to retirees’ preoccupations.

Findings and Discussion

Voluntary Retirement

With reference to (Figure 2), participants who had perceived retirement positively prior to retirement described retirement as a “time for myself, to do what I want to do”. They looked forward to retirement and viewed retirement as a time for “more rest”, for a “healthier lifestyle”, for “family”, “for enjoyment”, and “to relax”. Having these positive perceptions of retirement enabled retirees to look forward to retirement. Participants had different ways of using retirement as a time for themselves. Some became actively involved in community activities, such as morning exercises at the park, Zumba dancing, community karaoke, card games and board games at the residential community centers. Physical activities took on a group form or with at least one companion.

In cases which the participants were obliged to retire (e.g. due to mandatory retirement age), retirement was not viewed negatively if the participant also felt that it was time to retire. The sense of acceptance and the willingness to retire despite having a lack of control over the time and manner of retirement, had helped to negate the sense of undesirability for their lack of control over their retirement. A 62-year old female retiree said “I looked forward to retirement. Finally, can have time for myself and do what I want to do”. A 66-year old male retiree added that “I decided that I have worked enough. I spent two thirds of my life working. My children are all grown up now. There is no reason for me to keep working. It is time to enjoy retirement” However, even individuals who were well-prepared for retirement and had desired retirement may struggle with major adjustments as retirement.

A 69-year old male retiree shared that

“I suffered “withdrawal symptoms” after retirement because I need to feel that my life has value but I didn’t have any work identity nor can contribute after retirement, till I was given an advisory role at the union.……..After retirement, I felt like was “stepping off the cliff”, despite planning and preparing myself for it, for two years. I used to be sought after so I felt needed when I was working. I felt useless after retirement. We need to feel useful and have a sense of purpose in life” Following the acceptance of retirement, there was a re-prioritizing of life goals. Participants focused more on health and well-being by exercising more regularly, by setting aside more time for self or with spouse, and by providing instrumental help in grandparenting or caregiving.

Upon retirement, there was a stronger focus on personal wellbeing, social engagement and giving familial support.

Activity-substitution theory explained that older people will attempt to replace lost social roles with new social roles because of their desire to continue contributing to the well-being of others and maintain a purpose in life [28-31]. Activity-substitution theory also explained why retirees attempted to replace lost work roles with other social roles such as volunteering and community activities. While retirement may not increase contact and time with family and friends, (particularly if ample time was given to family and friends prior to retirement), the amount of instrumental support to family and friends may increase Lancee & Radl). Participants found it fulfilling and meaningful to help out with the grandchildren, ailing siblings or parents and to spend time with spouse. Participants also shared that they enjoyed social engagements in various forms – volunteering, meeting up with friends, making new friends and social interactions through community activities and socioemotional support from believers of the same faith. With the prioritization of relationships and in becoming a more holistic person, the theme of “balancing self and others” emerged. Participants desired to have a good balance of time and commitment on the activities and relationships that they enjoyed and activities that they deemed to be meaningful.

Involuntary Retirement

With reference to (Figure 4) common reasons for involuntary retirement were mandatory retirement age or re-employment age, retrenchment or when the retiree was obliged to meet a grandparenting request or caregiving demand. A 67-year old female retiree explained that “I didn’t have a choice. I reached 62 and they didn’t want to extend. A 69-year old male retiree also had the same predicament “When the HR didn’t offer to renew my contract, I also didn’t ask, so I just left when the contract expired. I could tell that they were not keen to keep me”. Another 70-year old female retiree said “the department closed down, so even if I wanted to carry on working, there are no other placements. They said that there is no other place for me and the other older colleagues retired together with me”.

A 60-year old male retiree grumbled

It is retrenchment The company closed but gave us compensation. After that, it is hard to find a job at my age. The younger ones forego the compensation package. They left and found new jobs. For the older ones like us, we know that it is difficult to find new jobs, so we stayed until the very last day, to get the compensation. I am one of the older ones, but still quite a number of years younger than the official retirement or re-employment age. I am stuck. I was retrenched at 59. The compensation cannot last me for long. I still have many years ahead before I am too old to work, yet at my age, no one wants to hire me” [32]. showed the economic vulnerability of individuals who involuntarily lost their jobs due to dismissal or firm closure in their late careers. They reported that the financial implications were severe, especially for those who lost their jobs in their early fifties. The disadvantage that they experienced will accumulate in terms of yearly income and continues for the next 10 years after involuntary job loss. This study noted that 20 out of a total of 103 participants had chosen “65” years old as their retirement age and explained that even if they were stressed and sick of working, they would have endured till 65 years old because 65 years old is the official age in which older adults can receive their monthly CPF pay outs. The choice of 65 years old as the desired retirement age indicated that financial security is important to participants. With the pay outs, they felt more assured to terminate their career employment, retire and use the pay outs to support their post-retirement living expenses.

Participants who had involuntary retirement were disappointed that they were unable to extend employment. Three participants described that they were depressed, especially for those who were retrenched or had left work under the impression that they were changing jobs rather than making a retirement decision. A 66-year old female retiree lamented “I was depressed you know, I lost at least 10kg. I was so angry with them for dismissing me. So unfair”

A 63-year old male retiree said

“I told my doctor that I am depressed. I didn’t think that it was retirement because I thought that I can find another job after I tender my resignation, but I haven’t been able to find anything suitable. I resigned because I was not happy with work. I feel happy whenever I can find a temporary job but I feel down and empty when the jobs end.”

A 61-year old male retiree said

“I feel so depressed because of my eye problem and cannot work. I want to work but I cannot find a job. Before I left, the competitors of my company told me to join them but none of them hired me after I left. I didn’t think that I was retiring. I thought that I was resigning from the company and moving on to other companies. My eye problem is affecting me too. I have to go for regular medical appointments. I hope to recover fast then I can get a job”. For those who still struggled accepting retirement or were adjusting to retirement, the common attitudes observed were that “it is not time for retirement yet”, “scary” and “boring”. They feared having too much time and not knowing how to occupy their time. They felt financially insecure especially if health fails later on. Participants with involuntary retirement felt unfairly treated because they felt the government and organization had no right to decide when they should stop work.

Apart from preoccupations and a shift of focus to social engagements and familial commitments, participants with involuntary retirement used training and job search as coping mechanisms. Participants who desired bridge employment attended courses for skills upgrading and to network with others to hopefully increase their chances of finding bridge employment.

Successful Transition into Retirement

Freund defined successful ageing as “a level of functioning that allows one to strive to fulfil personal goals and maintain personal standards and is, to a substantial degree, a result of one’s having successfully managed internal and external resources throughout one’s life span”. While this study found Freund’s definition to be meaningful in understanding what constitutes successful ageing, the data suggested that successful ageing is possible if retirees adapted well to life transitions and changes, even if they have not successfully managed internal and external resources throughout one’s life span. This adaptation required successful managing of internal and external resources at the point of transitioning rather than throughout one’s life span. For instance, retirees who were too busy with work and did not maintain strong friendships throughout their life span, compensated by actively participating in social and group activities in the community to make friends and be socially engaged.

This study observed that apart from the balance of self and others and the shift in priorities, participants who had successfully adjusted to retirement had the following perceptions and values (Table 4). If participants were not tied down by health issues, caregiving or grandparenting demands, this study observed that most participants followed two common courses of retirement transition in the first five years of their retirement. In the first kind of retirement transition, retirees were faced with the challenge of having too much time and not being sufficiently occupied, but gradually settled into the retirement mode with social and community activities, religious activities or voluntary work. Others prioritized engagement in bridge employment on a part-time or ad-hoc basis.

In the second kind of retirement transition, these retirees relished the newfound freedom and time for themselves. They embarked on a retirement journey defined by what they wanted to have and not merely by occupying themselves with activities for the sake of occupying themselves. A 71-year old female retiree said “actually, there isn’t enough time. Many people think that retirement means that there is a lot of time to spare but I am occupied every day and I enjoy my life”. These retirees rekindled their passion for past hobbies (such as photography and baking), took up new skills, formed new passion (such as knitting, investment and gardening) and also redefined life with activities that they considered to be meaningful (such as voluntary work and church ministry work). They did not experience the challenge of having too much time but stepped into the next phase of life with zest. A 65-year old female retiree said “I am involved in a recycling project with the national library and I am very happy that the minister is interested in it. They want us to share it with others so I will be quite busy advancing this project for them”.

A 60-year old female retiree said

“I adjusted quite fast. I didn’t feel like I didn’t know what to do after retirement. I took at least a few weeks to plan for each overseas trip and then travelled with my husband to places. We went for a few holidays in the first year, then we think that this is not sustainable, so we took on part-time jobs. I work as a parttime receptionist and he drives the taxi now, on a part-time basis” (Figure 5). However, if the activities were not group-based or lacking in the social element (e.g. gardening and knitting), then the passion was less sustainable. A 71-year old male retiree said “I was very happy at first because I finally get to do gardening. I spent a lot of time on gardening then it loses its appeal after a year. Now I think about getting a job again”. Regardless of whether participants’ retirement transition followed the first or second course, the key element was the social connectedness in these activities. The interest was more sustainable when there was companionship and interactions with others.

A 68-year old male retiree said

“In the first one to two years after retirement, I was more satisfied with my retirement because I enjoy spending a lot of time learning about photography and travelling to places to take pictures. I also get to make like-minded friends when I do nature photography at the parks and join photography groups in Facebook. I still enjoy photography now, but the level of excitement is not as high and sometimes I feel like finding something else to do”. The socio-emotional support derived from social connectedness through friendships and social interactions with others was crucial in helping participants adjust to retirement challenges and then find fulfilment in post-retirement years. Social emotional support is a coping mechanism and an important resource for successful ageing.

Post-retirement Lifestyle – Need to be Occupied but Not Necessarily Structured

While participants had routine activities, they did not seem to like a fixed schedule and preferred having a semi-structured lifestyle. Participants who were actively involved in group activities had fixed timings for these activities e.g. morning exercises from 8 am to 10 am every Monday to Friday, Zumba dancing every Tuesday night and Karaoke at the residential committee center every Wednesday afternoon. However, the other non-group activities were more fluid in nature. For example, most participants did household chores, took naps and met their friends over meals a few times a week. These activities had no fixed schedule. Participants explained that they did not need a structured lifestyle because they liked to have control over their time and do what they want to do, whenever they felt like it. In fact, they welcomed the flexibility as compared to the structured lifestyle they had when they were working. A 67-year old male retiree said, “I just need to have things to do, I don’t need to have fixed schedules”.

Participants also explained that it was not the structure in life that helped them cope with the loss of work life. More importantly, they needed to be occupied every day and exert control over how much involvement they would like to have in the activities. In this manner, they had activities to look forward to, and struck a good balance between social engagements and personal time. A 64- year old male retiree said Its ok, I think that it is a good break from the structured life when working. I don’t feel very free, but I feel freedom”.

Not all participants were occupied with social activities or family commitments, some spent a substantial amount of time with their spouse, some were actively involved in church activities and some were actively involved in voluntary work. There was not a fixed or ideal retiree lifestyle that was identified through the interviews, but what stood out was the importance of being balanced, engaged or occupied and having the freedom to enjoy what they wanted to do. These principles were common amongst all the ideal retiree lifestyles described by the participants.

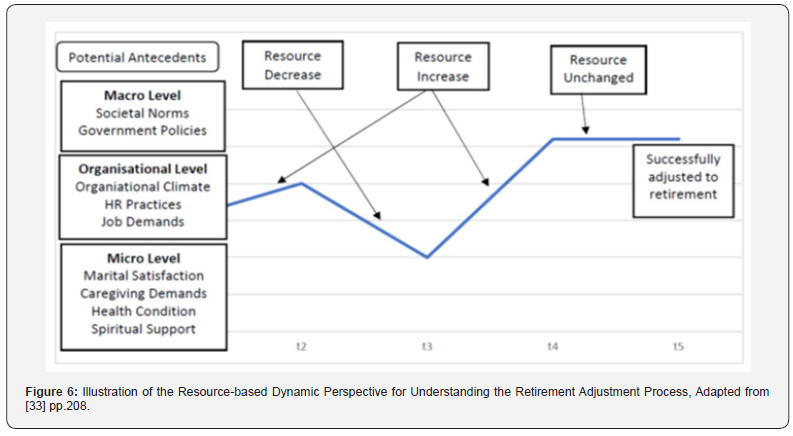

Retirement Adjustment

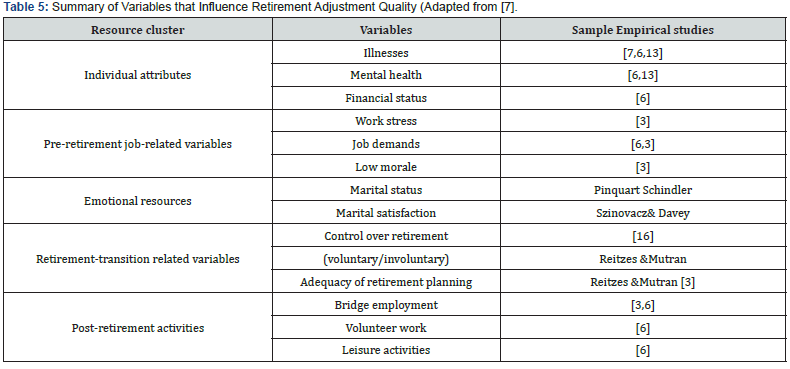

This study had identified the importance of social connectedness as a coping mechanism in assisting older adults through retirement. In applying the findings from this study into the resource-based dynamic perspective for understanding the retirement adjustment process [33] social connectedness can be deemed as a socio-emotional resource. Even though studies on the impact of resources on retirement adjustment vary in terms of the types of resources studied and the resultant impact, the findings and discussion in this study largely tallies with the resource-based dynamic perspective. This study supports the perspective that resources are significant determinants of retirement adjustment. Based on this study’s findings that social connectedness is an important coping mechanism, it is assumed that social connectedness is likened to socio-emotional resources in retirement adjustment (Table 5).

Wang et al. used the resource-based dynamic perspective to understand and explain the retirement adjustment process. Studies on retirement adjustment and resource-based perspective Wang assumed that adjustment is reached when the retirees are no longer preoccupied with the retirement transition but are able to integrate retirement into their lives [34] (Figure 6). The central premise of this perspective is that retirement adjustment is influenced by the individual’s access to resources. Resources are defined as “entities that either are centrally valued in their own right, or act as means to obtain centrally valued ends” [35]. Availability and access to resources are identified to be key factors in influencing retirement adjustment and the resulting life satisfaction. It is assumed that more resources will lead to fewer adjustment issues and greater well-being [36-38].

Conclusion

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first study to create and use the bi-directional coding analytical method to improve the validity of the findings. Going forward, bi-directional coding method needs to be tested on large scale qualitative studies in order to assess the reliability of this method. Using such a qualitative analytical strategy, social connectedness was identified to be a key coping mechanism for successful retirement transition. It is recommended that governments support community groups to promote opportunities for social connectedness to ease the transition of older adults into retirement and reduce possible isolationism and loneliness of older adults.

References

- Heybroek L, Haynes M, Baxter J (2015) Life Satisfaction and Retirement in Australia: A Longitudinal Approach. Work, Aging and Retirement 1(2): 166-180.

- Muratore AM, Earl JK, Collins CG (2014) Understanding Heterogeneity in Adaptation to Retirement: A Growth Mixture Modeling Approach. Int J Aging Hum Dev 79(2): 131-156.

- Wang M (2007) Profiling Retirees in the Retirement Transition and Adjustment Process: Examining the Longitudinal Change Patterns of Retirees’ Psychological Well-being. J Appl Psychol 92(2): 455-474.

- Earl JK, Gerrans P, Halim VA (2015) Active and Adjusted: Investigating the Contribution of Leisure, Health and Psychosocial Factors to Retirement Adjustment. Leisure Sciences 37(4): 354-372.

- Muratore AM, Earl JK (2015) Improving Retirement Outcomes: The Role of Resources-retirement Planning and Transition Characteristics. Ageing & Society35(10): 2100-2140.

- Kim JE, Moen P (2002) Retirement Experiences, Gender, and Psychological Well-being: A Life-course, Ecological Model. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 57(3): 212-222.

- Hansson I, Buratti S, Thorvaldsson V, Johansson B, Berg AI (2018) Changes in Life Satisfaction in the Retirement Transition: Interaction Effects of Transition Type and Individual Resources. Work Aging and Retirement 4(4): 352-366.

- Cahill KE, Giandrea MD, Quinn JF (2012) Bridge employment. Oxford Handbooks Online, 293-310.

- Shultz KS, Wang M (2011) Psychological Perspectives on the Changing Nature of Retirement. American Psychologist 66(4): 170-179.

- Wang M, Henkens K, van Solinge H (2011) A Review of Theoretical and Empirical Advancements. Am Psychol 66(3): 204-213.

- Wang M, Shultz KS (2010) Employee Retirement: A Review and Recommendations for Future Investigation. Journal of Management 36(1): 172-206.

- Zhan Y, Wang M (2015) Bridge Employment: Conceptualizations and New Directions for Future Research. Aging Workers and the Employee-Employer Relationship, 203-220.

- Wang M, Shi J (2014) Psychological Research on Retirement. Annual Review of Psychology 65: 209-233.

- Kimmel DC, Price KF, Walker (1978) Retirement choice and retirement satisfaction. J Gerontol 33(4): 575-585.

- Van Solinge H (2013) Adjustment to Retirement. In M. Wang (Edn), The Oxford handbook of retirement Oxford University Press 311-324.

- Van Solinge H, Henkens K (2008) Adjustment to and Satisfaction with Retirement: Two of a Kind? Psychology and Aging 23(2): 422-434.

- Barbosa LM, Monteiro B, Murta SG (2016) Retirement Adjustment Predictors-A Systematic Review. Work Aging and Retirement 2(2): 262-280.

- Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (2009) Oxford handbook of positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, pp. 752.

- Sim J, Bartlam B, Bernard M (2011) The CASP-19 as a measure of quality of life in old age: Evaluation of its use in a retirement community. Qual Life Res 20(7): 997-1004.

- Schoonenboom J, Johnson RB, Köln Z Soziol (2017) 69(Suppl 2): 107.

- Boyatzis RE (1998) Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic analysis and Code development, SAGE pp.200.

- Smith JA, Flower P, Larkin M (2009) Interpretative Phenemenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. Qualitative Research in Psychology. Br J Pain 9(1):41-42.

- Van Manen M (1997) From Meaning to Method. Qualitative Health Research 7(3): 345-369.

- Landridge D (2018) Phenomenological Psychology, Open Research Online.

- Christians CG, Carey JW (1989) The Logic and Aims of Qualitative Research. Research Methods in Mass Communication 7(3): 354-374.

- Kleiman S (2004) Phenomenology: To Wonder and Search for Meanings. Nurse Res 11(4): 7-19.

- Pickens J (2005) Attitudes and Perceptions. Organizational Behavior in Health Care. Jones and Bartlett Publishers pp.45.

- Chambre SM (1984) Is Volunteering a Substitute for Role Loss in Old age? An Empirical Test of Activity Theory. Gerontologist 24(3): 292-298.

- Lancee B, Radl J (2012) Social Connectedness and the Transition from Work to Retirement. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 67(4): 481-490.

- Mutchler JE, Burr JA, Caro FG (2003) From Paid Worker to Volunteer: Leaving the Paid Workforce and Volunteering in Later Life. Social Forces 81(4): 1267-1293.

- Van den Bogaard L (2017) Leaving quietly? A Quantitative Study of Retirement Rituals and How They Affect Life Satisfaction. Work, Aging and Retirement. 3(1): 55-65.

- DammanM, Henkens K (2017) Constrained Agency in Later Working Lives: Introduction to the Special Issue. Work, Aging and Retirement3(3): 225-230.

- Wang M, Henkens K, van Solinge H (2011) A Review of Theoretical and Empirical Advancements. American Psychologist 66(3): 204-213.

- Schlossberg NK (1981) A Model for Analyzing Human Adaptation to Transition. The Counseling Psychologist 9(2): 2-18.

- Hobfoll SE (2002) Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Review of General Psychology 6(4): 307-324.

- Earl C, Taylor P (2015) Is Workplace Flexibility a Good Policy? Evaluating the Efficacy of Age Management Strategies for Older Women Workers. 1(2): 214-226.

- Freund AM (2008) Successful Aging as Management of Resources: The Role of Selection, Optimization, and Compensation. Research in Human Development5(2): 94-106.

- Schoonenboom J, Johnson RB, Köln Z Soziol (2017) 69(Suppl 2): 107.