Occupational Participation and Quality of Life for Older Adults Residing in Assisted Living

Zilyte G, McIlwain L, Knecht-Sabres, L

1Midwestern University, USA

2Greta Zilyte, OTS, Lindsay McIlwain, OTD, and Lisa Knecht-Sabres, DHS, OTR/L Occupational Therapy Program , Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL. USA

Submission: May 12, 2020; Published: May 27, 2020

*Corresponding author: Lisa Knecht-Sabres, DHS, OTR/L, Midwestern University, USA

How to cite this article: Zilyte G, McIlwain L, Knecht-Sabres L. Occupational Participation and Quality of Life for Older Adults Residing in Assisted Living. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2020; 5(4): 555667. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2020.05.555667

Abstract

Introduction: Activities offered at assisted living facilities (ALFs) tend to be generic in nature, putting its residents at risk for occupational deprivation (Westberg, Gaspar, & Schein, 2017). The primary objectives of this study were to explore activity engagement in an ALF, as well as understand quality of life (QOL) related to occupational participation.

Methods: A concurrent mixed methods design was used to collect data from 13 older adults residing in an ALF via questionnaires and individual interviews. Results were compared to identify patterns, using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis.

Results: Fifty-six percent of the participants indicated a decrease in QOL after moving to the ALF, while 77% expressed that their interests were not gathered by the facility. Qualitative data revealed five themes: socialization is a motivating factor to engage in activities, engagement in activities influences QOL, other residents in the facility affect QOL, staff influence residents’ QOL, and a variety of barriers limit activity engagement.

Conclusion: Occupational therapy practitioners could play a valuable role in enhancing the engagement of meaningful activities through consultation regarding the activities offered and by adapting activities to maximize participation.

Keywords: Occupational therapy; Assisted Living Facilities; Meaningful Activities; Quality of Life

Introduction

Currently in the United States, the population of individuals 65 years and older is over 40 million and is estimated to reach 92 million by 2040 [1]. As a result, the number of people requiring out of home care will grow immensely over the next 20 years. Today, assisted living facilities (ALFs) are growing quicker than any other senior housing option [2]; roughly 40,000 ALFs exist, which is more than double that of nursing homes [3]. Although facility regulations differ by each state, most ALFs offer assistance with activities of daily life and various instrumental activities of daily life, as well as a plethora of recreational and social activities [2]. Older adults transitioning into an ALF often experience limitations related to participation in leisure activities and ability to remain engaged in meaningful occupations, affecting their overall quality of life (QOL) [4]. As a result, this study sought to further explore the residents’ perceptions of their QOL, as well as to better understand how activities at ALFs impact occupational engagement and QOL.

Quality of Life and Activity Engagement

Occupational roles are maintained through continued participation in valued occupations and are related to increased well-being [5]. Additionally, leisure participation has been found to be a major factor in maintaining one’s health and continuing to live a meaningful life [6,7]. When facilities offer opportunities for engagement in purposeful activities and relationships, residents have reported higher life satisfaction and morale, as well as better functional mobility and overall health [8-10]. Furthermore, subjective and observed levels of happiness have been found to be higher among residents of ALFs when they were involved in activities [11].

Social engagement is considered to be a vital factor affecting older adults’ health and psychological well-being [8]. Although residents in ALFs may maintain social contact and support from family members and friends in the community, positive social interactions with other residents and staff consistently indicate higher self-reported life satisfaction, enhanced QOL, and feelings of being at home [12]. Social engagement has also been connected to reduced rates of mortality, slowing of functional deterioration, fewer depressive symptoms, and a decreased risk of cognitive impairment [8].

Conversely, situations in which individuals lacked social roles and active involvement in meaningful activities, decreased health-related QOL as well as, cognitive and physical decline [13]. Furthermore, among people in ALFs, higher depressive symptoms have been observed in residents with lower social engagement, suggesting that disengagement is a contributing risk factor for mental health concerns in the population [14].

Supports for Activity Engagement

Throughout the literature, several supports for activity engagement in ALFs were identified. These included: staff support and activity adaptations, responsiveness to residents’ wants and needs, and residents’ continuation of roles. Researchers have discovered that staff who take the time to learn about residents are better able to support the efforts of these older adults, leading to meaningful social interactions and decreased feelings of isolation [15], as well as increased weekly activity attendance [16,17]. Researchers found that when residents’ input was considered by the facility, activities had higher participation rates [18,19]. ALFs with more channels to promote activity, including verbal reminders from staff, also had more active residents [20,21]. The most successful activities were well planned, clearly communicated, and encouraged participation [18]. Additionally, including individual adaptations ensured residents’ continued engagement in meaningful occupations [22].

Lastly, performing valued roles allowed residents to preserve former identities, gain enhanced feelings of independence [22], and maximize enjoyment [18]. Unfortunately, many residents in ALFs are not participating in activities that maintain treasured roles [2].

Barriers to Occupational Participation

Several barriers for activity engagement in ALFs were also identified. These included: cognitive impairment, accessibility, inadequate assistance, and offered activities. As the literature supports, decreased participation in activities may be related to intentional avoidance of other residents. Pirhonen and Pietila [19] emphasized that some residents of ALFs viewed their peers with cognitive impairments as bothersome to interact with, resulting in residents choosing to stay within the confines of their rooms. Similarly, Park et al. [17] noted that those who perceived certain residential peers as having lower cognitive functioning led to avoidance and a decreased desire to create friendships with them.

Another barrier to occupational participation is overall accessibility, related to various personal and contextual factors. When residents move to an ALFs, means of transportation often dwindle, while distance from family and friends grows, resulting in reduced involvement in community activities [23]. and a feeling of separation from previous social partners [24]. Health decline was noted as a factor which inhibited visitors from interacting with older adults residing in ALFs [24], with physical impairments specifically preventing participation in certain treasured occupations within the facility [19]. The physical layout of the ALF presents as an additional factor for decreased participation in activities. For instance, Ball et al. [22] noted that ALFs lacking handrails in the hallways, wheelchair accessibility, and various issues related to the outdoor areas, prevented older adults from accessing activities and events offered at the facility. Unfortunately, even though the staff to resident ratio within facilities often met legal expectations, the time constraints placed upon staff did not allow them to offer residents the physical assistance needed to enable participation in numerous activities. Ball et al. [19,22] echoed these results, finding that inadequate staffing resources created barriers to residents’ independence and participation in activities; specifically noting that residents may not initiate asking for help when needed, because they are empathetic to the staffs’ busy workload.

Lastly, activity programming within AFLs presents as another prevalent barrier to meaningful activity participation for older adults. Programming is primarily based on generic assumed preferences [13], typically including things like exercise programs, religious services, puzzles, games, arts and crafts, and entertainment [25]. Many programs did not take residents’ individual differences and interests into account [10,17] and, in turn, residents did not consider the offered activities interesting or stimulating [26]. Although older adults expressed that they participated in activities at the facility, numerous of these activities were not considered meaningful or what they truly desired [17]. Similarly, Cummings [27] found that residents participated in four social activities on average per week; however, Westberg, Gaspar, and Schein (2017) discovered that participants were only engaged about half of the time during planned activities. It should be noted that residents reported recommending ideas for meaningful activities to staff members, but their suggestions were not implemented [17]. Egan et al. [31] echoed these concerns, asserting that having no mechanism to follow through with resident ideas was a barrier to activity engagement.

Purpose of the Study

Occupational deprivation is defined as the prevention of engagement in meaningful activities [13]. Occupational deprivation is considered a form of occupational injustice that can occur when residents of ALFs experience any of the above outlined social, environmental, or institutional barriers. Residents who are not offered the opportunity to engage in valued leisure occupations are being deprived of the associated physical and psychosocial benefits of meaningful engagement in activities, leading to negative cognitive, social, emotional, and physical outcomes [13]. By exploring the connections between residents in ALFs, activity participation, and QOL, occupational therapists will better be able to serve this vulnerable population. As Jenkins et al. [9] supports, improving the health and QOL of aging populations involves activity participation that is geared to an individual’s preferences.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to contribute to the literature by developing an understanding of specific factors that impact older adults’ ability to participate in meaningful occupations within the ALF setting. Although previous studies address activity engagement within ALFs, the researchers of this study desired to gain a deeper understanding through the opinions of residents and their lived experiences related to participation in meaningful activities. This study aimed to address the following research questions:

a. Do ALFs take the interests of their residents into account when planning activities?

b. What are the supports that allow older adults to maintain involvement in leisure activities?

c. What are the barriers that prevent older adults from maintaining involvement in leisure activities?

d. Does subjective perception of quality of life change after moving into an ALF?

e. Do residents perceive their lives as enjoyable and worthwhile?

Methods

Research design

This study utilized a convergent mixed methods approach, which allowed the researchers to bring together the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative methodology [28]. A mixed methods design was chosen for this study because it enabled the researchers to more comprehensively understand the researchers’ questions and because it is known to enhance credibility [28]. More specifically, a convergent mixed methods approach was used to determine if a change in activity engagement occurred after a move into an ALF and to explore the supports and barriers for occupational participation in ALFs.

Participants

Before participants were recruited, researchers obtained approval from the institutional review board at Midwestern University. Participants were recruited using convenience sampling and consisted of 13 residents living in three different assisted living units of an ALF in the Midwest of the United States of America. All participants were females. Three participants (23%) lived in the 100 unit, seven participants (54%) lived in the 200 unit, and three participants (23%) lived in the 300 unit. The median age of the participants was 85, with a range of 80 to 98 years old. The median time that the residents had resided in their respective unit was between three and four years, with a range of three months to over five years.

Inclusion criteria for this study required participants to be 65 years of age or older and have resided in the ALF for at least 3 months. Additional requirements included that participants speak English, be able to provide written consent, and be identified by the life enrichment aide as cognitively able to participate in this research project. With the assistance of the ALF staff, recruitment flyers distributed to residents who met the inclusion criteria. All participants were provided with an opportunity to ask questions and to review the consent forms. The consent process also informed individuals of their right to withdraw from the study for any reason, at any time, without consequences.

Data Collection

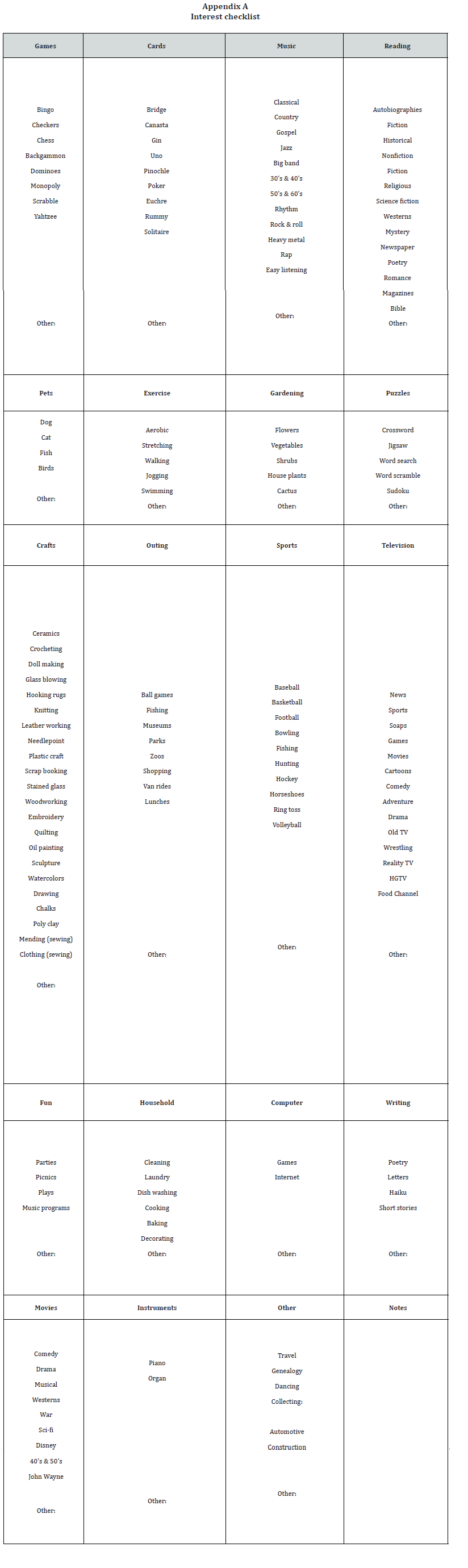

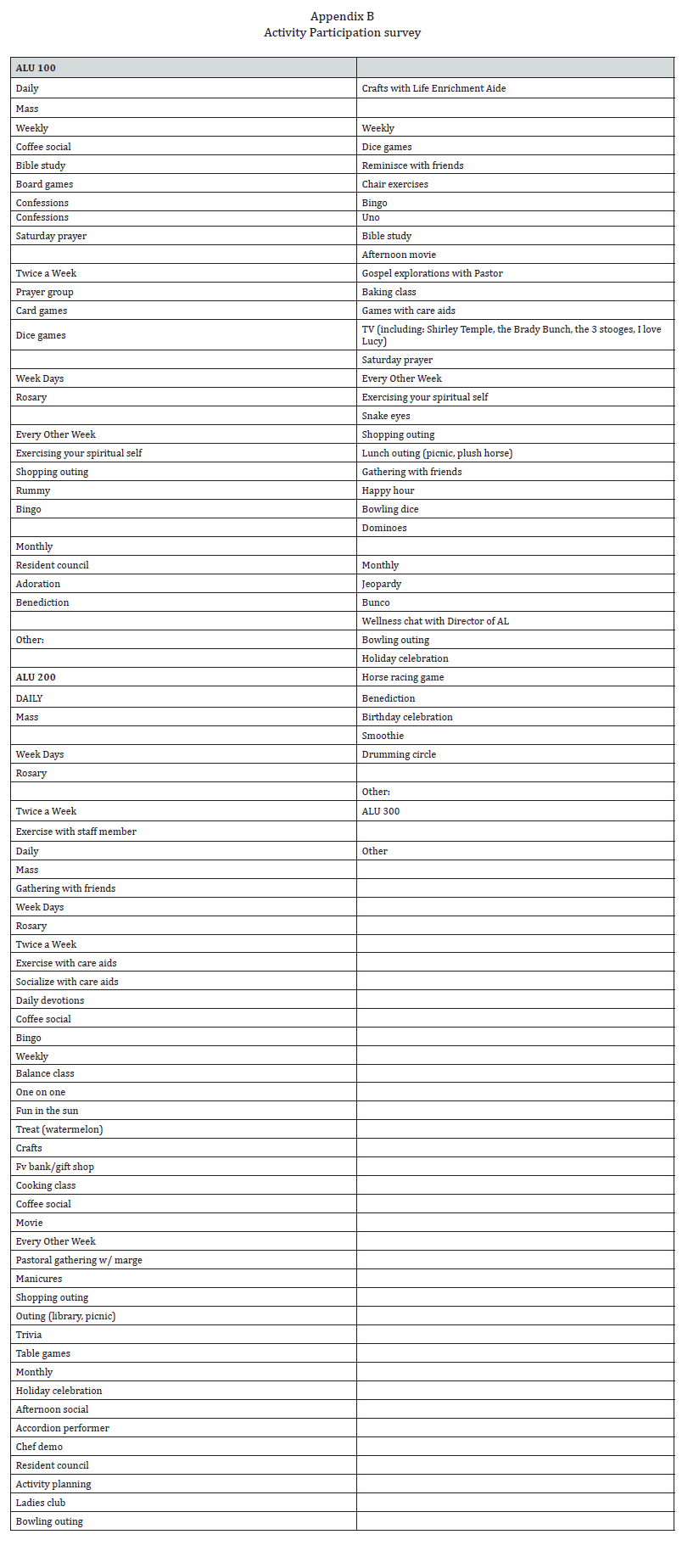

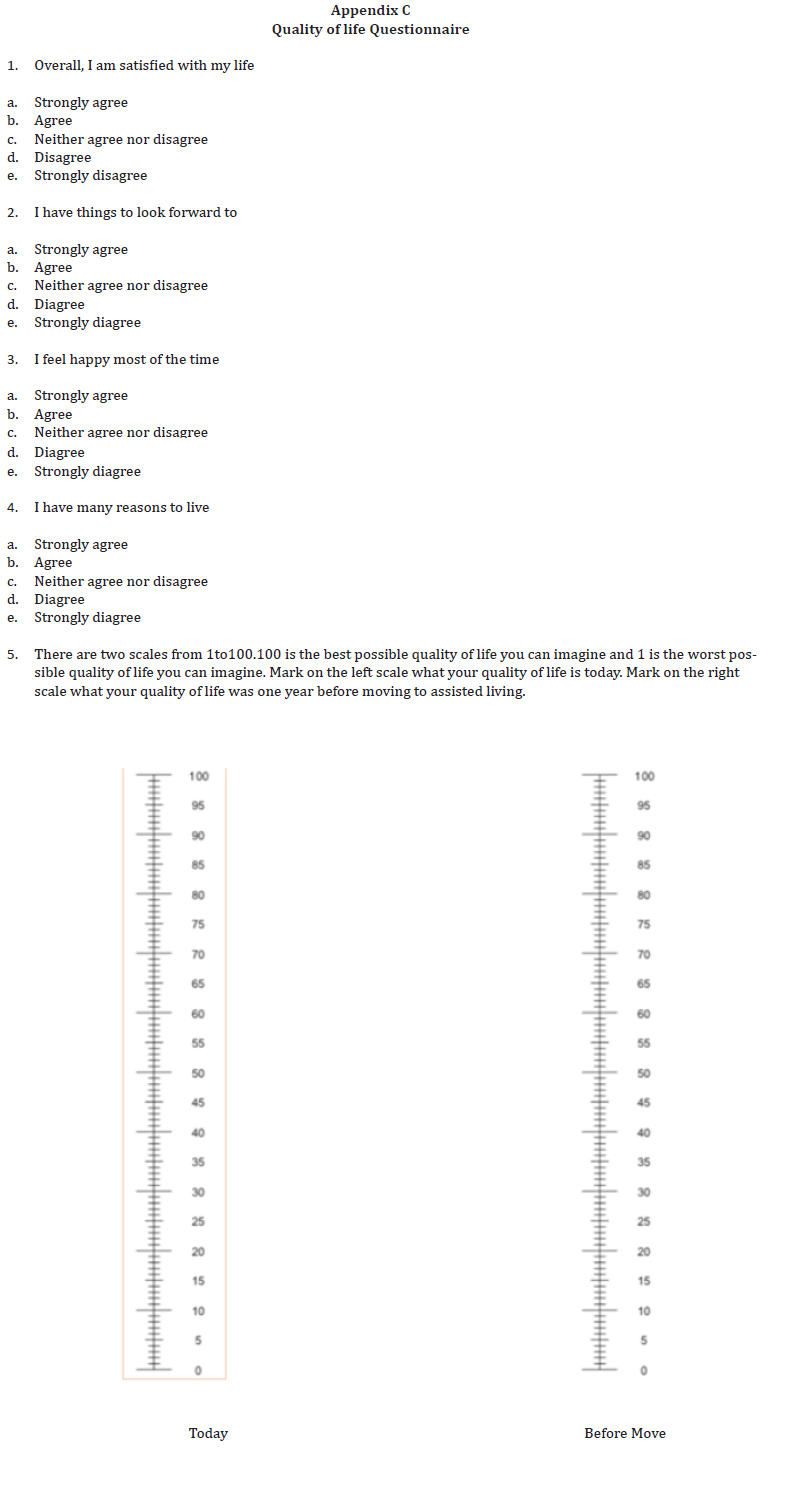

Several researcher-developed questionnaires were utilized to gather quantitative data regarding the participants’ interests, involvement in activities, and self-perceived QOL. The first questionnaire required participants to identify which activities they would be interested in participating in (Appendix A). A list of activities currently offered within their facility was also used to gather information regarding which activities they currently partake in and how often they participate in those activities (Appendix B). If participants indicated that they engaged in an offered activity, they were then asked whether they did so on a daily, weekly, monthly, or occasional basis. Another researcherdeveloped questionnaire consisting of four questions on a Likert scale (1 = strongly agree; 2 = agree; 3 = neither agree or disagree; 4 = disagree; 5 = strongly disagree) was used to gather additional quantitative information regarding the participants’ QOL (Appendix C); this also included a self-perceived rating of QOL today and one year before moving into the ALF on a scale from 0-100.

Qualitative data was gathered from semi-structured interviews in order to better understand participants’ engagement in meaningful activities, the supports and barriers to participation, their social lives within the facility, and suggestions for improving current activity offerings (Appendix D). Semistructured interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Throughout the process of data collection, researchers performed member checks in order to verify and validate the participants’ responses to help improve the accuracy, credibility, and validity of the qualitative data.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data was entered into an excel spreadsheet and analyzed with descriptive statistics. Using thematic analysis, all interviews were coded line-by-line, in order to determine patterns that emerged within individual interviews. Researchers completed an open coding process, once separately and numerous times together, to ensure consensus. Using a process of constant comparison, codes were first determined by common categories and then condensed into more meaningful themes. Rigor was enhanced by utilizing constant comparison with multiple coders and expert examination, as well as triangulation [29].

Results

Quantitative data

Interest checklist Out of 31 items on the interest checklist, participants chose between 11 and 26 activities that they were currently interested in, with a median of 20 interests. Pets, music, exercise, and games/puzzles were reported most frequently as interests, with 13 people (100%) stating their interest in pets and/ or music, and 12 people (92%) stating their interest in exercise and/or games/puzzles. Collecting items, automotive, writing, genealogy, and instruments were reported least frequently as interests, with 3 people (23%) stating their interest in collecting and/or automotive, and 4 people (31%) stating their respective interests in writing, genealogy, and/or instruments.

Activities offered within the facility The 100 unit offered 17 activities for its residents; the participants on this unit (n=3) indicated that they engaged in 11 of the activities. Bingo and mass were the most commonly attended activities (100%). None of the participants on this unit reported participation in the following activities: coffee social, prayer group, bible study, Saturday prayer, exercising your spiritual self, and the shopping outing.

The 200 unit offered 34 activities for its residents; the participants on this unit (n=7) indicated that they attended 33 of the offered activities. Mass (86%), holiday and/or birthday celebrations (71%), and exercise with a staff member (71%) were reported as the most commonly participated in activities. Exercising your spiritual self was the single activity in which none of the residents on this unit participated in. The 300 unit offered 31 activities for its residents, the participants on this unit (n=3) indicated that they participated in 19 of the offered activities. Mass, bingo, gathering with friends, and fun in the sun were reported as the activities with the most engagement (100%). More than 10 activities had 0% participation in this unit.

It is noteworthy that several residents mentioned that they were unaware of certain activities being offered within the facility, while some also stated that they were unsure of how often they attended specific activities. Furthermore, a majority of participants (77%) indicated that their personal interests were either not gathered by the facility or that they did not recall this ever-taking place.

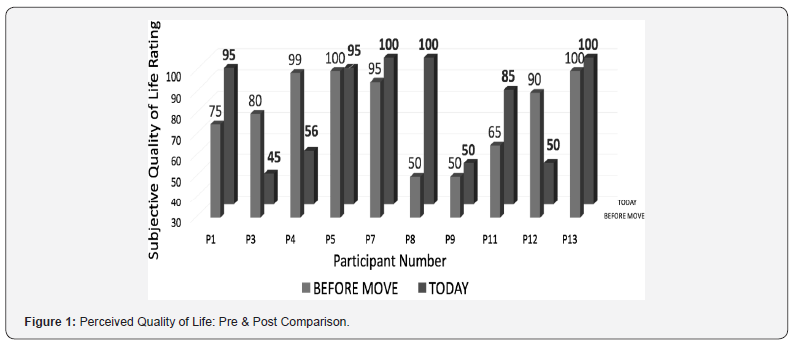

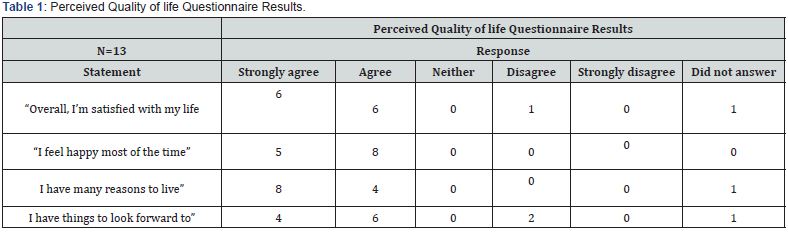

Quality of life When asked to rate their QOL, on a scale from 1-100, one year prior to moving into the ALF and on the date of the interview, 4 participants (31%) felt that their QOL had increased after moving to the ALF, 2 people (16%) felt that their QOL was the same, and 5 people (30%) felt that their QOL had decreased after a move to the ALF (Figure 1). One person (8%) was unsure of how to answer the question and another (8%) felt as though he/ she could not accurately answer this question. (Table 1) describes the residents’ perceived QOL on the QOL Questionnaire

Qualitative data

Analysis of the qualitative data revealed five themes related to how residents of an ALF experience their lives: (1) engagement in activities influences quality of life; (2) other residents affect life in the facility; (3) staff affect overall life in the facility life in the facility; (4) socialization is a benefit of engagement in activities; and (5) a variety of barriers limit engagement in activities.

Engagement in activities influences quality of life: The participants in this study indicated that participation in activities within the ALF positively affects their QOL. For instance, one resident expressed her opinion of when she felt the happiest at the facility:

I went to the ... (activity) and I was really happy and I felt bad that I didn’t go the other times… So, I’m gonna go more now for sure, because I know it’s… really makes me happier to go and be with people and if I’m… feeling down it’s because I’m mostly not doing that.

Other residents also mentioned that attending activities had an effect on their emotions. Residents frequently reported that activities made them “feel good” or “feel better”. Similarly, another resident claimed that the positive effects of engagement in activities are a motivating factor for attending the offered activities and claimed that she attends them “because it’s best for (her)”.

Other residents affect overall life in the facility: Participants often commented on how fellow residents in the ALF can impact their overall QOL. For instance, numerous residents within the facility reported that some residents had cognitive impairments and that these deficits impacted socialization opportunities and quality of time spent with peers, as well as led to frustrating interactions. For example, one resident stated, “not all the (residents) can think, you know? They can’t remember. So, that’s the problem. Like, you come to the table, you sit, and nobody talks”. This was a common thread when residents spoke of relationships with others within the ALF. Another participant similarly stated, “I mean there aren’t many that are talkative. I look for ones that are able to answer me back”. Although these challenges exist for individuals within the facility, residents also shared worthwhile encounters and relationships with one another that positively impacted their lives. For instance, one participant stated, “the people we live with are lovely people. I enjoy them and seeing them” and another individual confirmed, “everybody is so friendly”.

Staff affect overall life in the facility: Another theme that emerged from the qualitative data related to the concept that staff at the ALF can have a significant impact on one’s QOL within the facility. Some participants spoke highly of the staff and acknowledged how they encouraged engagement in activities. One participant stated, “I mean that girl that does them... she’s excellent. She’s one if you’re sittin’ in your room, I get up and go with her”.

However, various participants also expressed their concern and sadness associated with the behavior of some of the staff members, making statements such as, “it makes me unhappy when I see some of the people, the way they treat ... older people”. When speaking of disappointment in how employees are trained at the facility, one participant said, “they should be trained; at least one session in serving… how to serve, you know? ... They take care of people, but they don’t know… and some people are not cut out for this kind of work”. Likewise, a participant conveyed concerns with staff supervision and the ways staff perform services:

People in responsible positions should be checked on occasionally, because it seems like … nobody follows up to see that they are doing what they’re supposed to. And for example, sometimes all that the people are doing is filling in time and calling all their friends ... instead of doing their jobs. So, it’s very frustrating that you can’t get some results and ... service, because they’re doing their own thing.

Socialization is a benefit of engaging in activities: Another theme that emerged from the qualitative data had to do with socialization being a benefit of engaging in the activities offered at the ALF. For instance, one participant said “They keep me involved with people and [I] socialize”. Another participant spoke passionately about why she enjoys her current activities; she stated, “it brings 2 or 3 of us together, that’s the companionship. That’s all beautiful. And second is the comradery that exists between us… Maybe we’re all old… so you know that you can relate to them”.

Variety of barriers limit engagement in activities: The majority of residents verbalized several barriers that limited their ability and/or willingness to participate in meaningful leisure activities. Among the most frequently mentioned barriers for participation in meaningful activities were: physical limitations, other responsibilities, and the inability to drive.

Physical limitations. The majority of participants (77%), stated that their physical condition served as a barrier to attending meaningful activities. Participants claimed that engagement in certain meaningful activities was “too much”, or that they were “not feeling up to it” that day. To expand, one resident stated, “I know what keeps me from being involved is my ill health... And my body, because it’s an old body and can’t go into meaningful activities. I could do some, but very limited”. Another resident also verbalized the impact that her physical condition has had on her psychosocially through the use of a metaphor, “sometimes I feel like I’m in jail, I never thought I would be so confined (by my body)”. Issues with accessibility of vehicles, family homes, and the activities themselves due to physical limitations were also a cause for decreased or lacking attendance for study participants.

Other responsibilities: About a third of the participants claimed that other activities, events, or visitors often got in the way of their attendance in both personal activities and those hosted by the ALF. For instance, one participant spoke about feeling unable to leave her room, “I would love to be downstairs with (activity aide), but you know I’m sort of in a bind, because, I’m sort of waiting for the therapist, or this, or that... and sometimes my daughter will come up…”. Other residents of this facility echoed these concerns, stating that they would attend activities, “if (they) have time”, “as long as it’s not conflicting with other (activities)”, and “if (they) don’t have to go see a doctor”.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to contribute to the literature by developing an understanding of specific factors that impact participation in meaningful occupations at ALFs. This study provides additional insight into the occupational lives of individuals within ALFs, supporting previous findings that indicate engagement in meaningful activities is related to overall QOL (Jenkins et al., 2002), and that individual and personal interests are not being taken into account when planning activities for residents of ALFs (Milte et. al., 2016). Further findings from this study also align with previous research related to barriers that affect activity engagement in those residing in ALFs, including health decline (Bennett et al., 2015), physical impairment, and the cognitive state of peer residents (Pirhonen & Pietila, 2016). Additionally, in some instances, staff members were found to positively impact residents’ QOL, which is substantiated by their vital role in supporting weekly activity attendance (Winstead et al., 2013; Park et al., 2009) and providing opportunities for valued social interactions (Polenick and Flora, 2011). On the other hand, at times, staff members were found to not display appropriate, professional behaviors or service performance, which supports research conclusions that staff also do not always offer adequate assistance for residents in ALFs (Pirhonen & Pietila, 2016; Ball et al., 2004). These unfavourable staff factors can limit activity engagement in ALFs (Ball et al., 2004) and negatively impact residents’ QOL.

Occupational justice, or the belief that individuals have a right to engage in diverse and meaningful occupations to meet one’s individual needs and to sustain QOL (Durocher, Gibson, & Rappolt, 2014), is commonly recognized and endorsed by occupational therapists. Occupational therapy practitioners are charged with addressing the needs of those who are experiencing occupational injustice and occupational deprivation. Occupational therapy practitioners could play a valuable role in enhancing older adults’ ability to engage in meaningful activities for those residing in an ALF, as meaningful and personalized activities are positively associated with QOL (Causey-Upton, 2015). Because occupational therapy practitioners are skilled at analyzing components of the person, occupation, and environment, an occupational therapist would be able to enhance occupational performance for residents in ALFs by modifying and adapting activities to provide “the just right” challenge. In other words, occupational therapy practitioners could use their expertise to modify activities so that residents can engage in meaningful activities, despite physical limitations. Furthermore, the literature and the results of this study imply that occupational therapy practitioners could consult with ALFs and provide education to staff members. These services would ensure that activities offered at the ALFs reflected the individual needs and preferences of its residents, thereby facilitating the engagement in meaningful occupations, helping to ease the transition into ALFs as well as promoting increased QOL.

Implications for future research

Although saturation of data was achieved, this study consisted of a small homogeneous sample of 13 participants who were all female and lived within the same ALF in the Midwest of the Unitred States. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be generalizable. However, the researchers are hopeful that the utilization of a mixed methods design increased the rigor and trustworthiness of the results. Recommendations for future studies include utilizing a larger sample size with increased diversity, as well as broadening the number and location of ALFs used for data collection.

A limited amount of recent research exists that examines the engagement in meaningful activities for individuals residing in ALFs. Further research is recommended to explore older adults’ QOL and their perception related to remaining engaged in valued occupations after transitioning into an ALF. It is suggested that future studies are intervention based and assess the perceived QOL before and after individualized, meaningful activities are implemented in the ALF. Similarly, future researchers are advised to assess the self-perceived QOL of residents in ALFs before and after occupational therapy consultation, in order to provide further evidence of the vital role that occupational therapy can play in enhancing meaningful, happy, and satisfying lives for older adults.

Conclusion

It is important to keep in mind that when an older adult transitions into an ALF, it can markedly change the individual’s daily routines and require major life adjustments, significantly impacting one’s self-efficacy and ability to engage in meaningful occupations. Likewise, health care providers and ALF staff must be aware of the vast physical changes that older adults moving into an ALF may be experiencing, which can also impact their ability to engage in meaningful occupations. Occupational therapy practitioners can provide consultation and direct services for older adults, in order to ease the transition into an ALF, enabling older adults to live life to the fullest.

References

- S. Department of Health and Human Services: Administration on Aging. (2012). A profile of older Americans: 2012.

- Horowitz B, Vanner E (2010) Relationships among active engagement in life activities and quality of life for assisted-living residents. Journal of Housing for The Elderly 24(2): 130-150.

- Assisted Living Federation of America. (2009) What is assisted living?

- Mulry CM (2012) Transitions to Assisted Living: A pilot study of residents’ occupational perspectives. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics 30(4): 328-343.

- Laliberte-Rudman D (2002) Linking occupation and identity: Lessons learned through qualitative exploration. Journal of Occupational Science 9(1): 12-19.

- Hutchinson SL, Nimrod G (2012) Leisure as a resource for successful aging by older adults with chronic health conditions. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 74(1): 41-65.

- Lampinen P, Heikkinen R, Kauppinen M, Heikkinen E (2006) Activity as a predictor of mental well-being among older adults. Aging & Mental Health 10(5): 454-466.

- Park NS (2009) The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology 28(4): 461-481.

- Jenkins KR, Pienta AM, Horgas AL (2002) Activity and health-related quality of life in continuing care retirement communities. Research on Aging 24(1): 124-149.

- Milte R, Shulver W, Killington M, Bradley C, Ratcliffe J, Crotty M (2016) Quality in residential care from the perspective of people living with dementia: The importance of personhood. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 63: 9-17.

- Watkins EE, Walmsley C, Poling A (2017) Self-reported happiness of older adults in an assisted living facility: Effects of being in activities. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 41(1): 87-97.

- Street D, Burge S, Quadagno J, Barrett A (2007) The salience of social relationships for resident well-being in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62(2): S129-S134.

- Causey-Upton R (2015) A model for quality of life: Occupational justice and leisure continuity for nursing home residents. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics 33(3): 175.

- Jang Y, Park NS, Dominguez DD, Molinari V (2014) Social engagement in older residents of assisted living facilities. Aging & Mental Health, 18(5): 642-647.

- Polenick CA, Flora SR (2011) Increasing social activity attendance in assisted living residents using personalized prompts and positive social attention. J Appl Gerontol (5)515-539.

- Winstead V, Anderson WA, Yost EA, Cotten SR, Warr A, et al. (2013) You Can Teach an Old Dog New Tricks: A Qualitative analysis of how residents of senior living communities may use the web to overcome spatial and social barriers. Journal of Applied Gerontology 32(5): 540-560.

- Park NS, Knapp MA, Shin HJ, Kinslow KM (2009) Mixed methods study of social engagement in assisted living communities: Challenges and implications for serving older men. J Gerontol Soc Work 52(8): 767-783.

- Koehn SD, Mahmood AN, Stott-Eveneshen S (2016) Quality of life for diverse older adults in assisted living: The centrality of control. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 59(7-8): 512-536.

- Pirhonen J, Pietilä I (2016) Perceived resident-facility fit and sense of control in assisted living. J Aging Stud 38: 47-56.

- Harris-Kojetin L, Kiefer K, Joseph A, Zimring C (2005) Encouraging physical activity among retirement community residents: the role of campus commitment, programming, staffing, promotion, financing and accreditation. Seniors Housing and Care Journal. 13(1): 3-20.

- Westberg K, Gaspar PM, Schein C (2017) Engagement of residents of assisted living and skilled nursing facility memory care units. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 41(4): 330-346.

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV (2004) Independence in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 18(4): 467-483.

- Cutchin MP, Chang PJ, Owen SV (2005) Expanding our understanding of the Assisted Living experience. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 19(1): 5-22.

- Bennett CR, Frankowski AC, Rubinstein RL, Peeples AD, Perez R (2015) Visitors and resident autonomy: Spoken and unspoken rules in assisted living.

- Muehlbauer P (2014) How do you keep older adults active in assisted living facilities? ONS Connect 29(3): 29.

- Goss RC, Beamish JO (2007) Assisted living facilities: best practices in design and management. Seniors Housing and Care Journal 15(1): 91-104.

- Cummings SM (2002) Predictors of psychological well-being among assisted-living residents. Health & Social Work 27(4): 293-302.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Brigitte C (2017) Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: Perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 36(4): 253-263.

- Durocher E, Gibson BE, Rappolt S (2014) Occupational justice: A conceptual review. Journal of Occupational Science, 21(4), 418-430.

- Egan MY, Dubouloz C, Leonard C, Paquet N, Carter M (2014) Engagement in personally valued occupations following stroke and a move to Assisted Living. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 32(1): 25-41.

- Gaugler JE, Kane R A (2005) Activity outcomes for assisted living residents compared to nursing home residents. Activities Adaptation & Aging 29(3): 33-58.