Citizens in Resilient European Societies are Happy Old

Wim JA van den Heuvel* and Marinela Olaroiu

University of Groningen,Spaubeek , Netherlands

Submission: August 21, 2019; Published: September 6, 2019

*Corresponding author:Wim J A van den Heuvel, University of Groningen,Spaubeek , Netherlands

How to cite this article: Wim J v d H, Marinela O. Citizens in Resilient European Societies are Happy Old. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2019; 5(1): 555655. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2019.04.555655

Abstract

European citizens become happy old, when they live in resilient societies.

Objective: A happy old population may be seen as a major challenge worldwide. However, ageing of the population is often seen as a major problem. Besides, old people are not happy per se. The objective of this study is to test the hypothesis, that in resilient countries citizens have a higher life expectancy and a higher overall life satisfaction, when old, as compared to less resilient countries.

Methods: This cross-national study collected data from 25 European countries in 2016 using data set of Eurostat and the European Social Survey. Life expectancy at birth and overall satisfaction with life of citizens 65 years and over are used to assess ‘happy old’. Resilience is assessed by 20 national indicators, including shared values and feelings on equity, trust and social cohesion of citizens and governmental investments in social protection and health care.

Results: Principal Component Analysis shows four resilience components: ‘trust and secure’, ‘following rules’, ‘equity’ and ‘protection and care investment’. Citizens become older and are – when old – more satisfied with life, when living in countries where citizens indicate they have trust in institutions and fellow citizens and feel secure, where governments invest in social protection and health care, and where citizens state it is important to follow rules, to be equally treated, to help each other, and to understand different people.

Discussion: This study is one of the first, which uses the concept resilience to understand which national characteristics may explain successful ageing. The results show that happier and older citizens live in resilient countries. Assessing resilience is still a matter of scientific dispute. The way resilience components are assessed in this study is promising and theoretically based. Moreover, these components are in line with indicators used in international documents and may be used for future studies on resilient societies. The way resilience is assessed as well as the results may not only be applied to nations, but also to communities and institutions.

Keywords: Ageing; Life satisfaction; Life expectancy; Resilience; Vulnerability; Trust

Introduction

Most people want to be happy and to become old. In European countries citizens become older and older but are not always happy when they are old. On the contrary, in 2016 the citizens of 65 years and over in the European Union are less satisfied with life as compared to younger ones [1]. However, this does not apply to all EU countries. [1,2]. In Bulgaria, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and Slovakia life satisfaction of older people is lower as compared to younger people, while in Denmark, Sweden and in the non-EU countries Norway and Switzerland life satisfaction of people of 65 and over is higher than of other age groups [1,3]. Such differences raise the question: what makes some (European) countries more successful in creating happy ageing as compared to others?

All European countries are confronted with an ageing population, causing dispute about sustainability of pension and health care systems and the role of technology, and how to face this demographic challenge [4]. Overall in the EU, the total cost of ageing (public spending on pensions, health care, long-term care, education and unemployment benefits), is expected to increase by 1.7 percentage points to 26.7% of GDP between 2016 and 2070 [5]. Recently, the OECD in cooperation with the EU published the state of health in Europe and advices member-states to anticipate on the demographic and technological changes and calls on health systems to become more resilient [6]. The latter is defined as ‘the capacity of health systems to adapt efficiently to changing economic, technological and demographic environments’ [6].

For some time, demographic changes have been seen as a major challenge for developed nations [7-9]. Studies dealing with these challenges call for exploring the role of resilience in relation to ageing [10,11]. The concept resilience is considered important to understand how communities, biological entities, ecological systems, and institutions are able to avoid or overcome crises or disasters by anticipating and (re)acting effectively to expected changes, are able to ‘bounce back’. Resilience indicates which capacities and means are needed to do so. Resilience has been conceptualized and applied in a various way and has therefore various definitions [12].

The concept of resilience has been developed in biological and psychological research to explain why some living systems (plants, animals, humans) could overcome adverse events and others could not, followed by studies on societal reactions to ecological changes and economic developments [13]. Besides to individuals, resilience is also applied to communities and nations to understand how institutions, politics and social context may deal with major social changes to maintain quality of life of citizens. Resilience assesses how well a system (community, organization, or nation) is able to recover (‘bouncing back’) in case of adverse events or even to anticipate (‘bouncing forward’) in case of expected adverse events by investing in security, public welfare, skills, and culture [14]. Building resilient societies should be seen as an international challenge as stated by the United Nations in 2015 with the mission: ‘Build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations, and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters by 2030.’ [15]. It is supposed, that societies, which have created resilient capacities and means, would be able to maintain quality of life for their citizens, despite challenging changes (like ageing of the population, financial crisis, climate change or geopolitical conflicts). Social resilience contributes to response to and to recover from large-scale social changes [16]. Cosco et al. [17] conclude based on a systematic review that the concept of resilience has not sufficiently addressed in studying successful ageing. Therefore, the concept of resilience could be important to understand and to learn how to become happy old [1, 10, 11]. Or as Windle et al. [18] suggest ‘resilience could be the key to explaining resistance to risk across the lifespan….’ Studies indicate, that resilience is related to life expectancy as well as to life satisfaction [19-22]. Zeng and Shen [19] show that resilience is related to advance ageing and suggest that promotion of resilience may have a positive effect on well-being of older citizens. Also, it is suggested that older citizens in good health may contribute to a resilient society [23].

Although the concept resilience is promising in various scientific domains, as an individual or as a system characteristic, the assessment of resilience is still problematic, i.e. no standardized measurements are available yet [24]. Serfillip et al. [24] define resilience as the capacity of people, communities, or systems to prepare for and to react to stressors and shocks in ways that limit vulnerability and promote sustainability and survival. Various components are proposed to assess the resilience of societies (for example sustenance, health, security, education, culture, and relationships [12,18], which may be seen as functions of communities and countries to realize a ‘resilient society’ [25]. To reach these functions specific resources and instruments are needed (institutions, infrastructure, services) realized by national policies and informal human interactions. Sharing values and rules and accepting regulations and control are needed for constructive interactions, i.e. individuals, families, organizations are able and willing to cooperate and to do so over time (despite flashbacks). To identify the resilience of a society the following components should be considered: proper infrastructure and services, the presence of shared values and the extent to which citizens feel vulnerable [12,18,24,25]. Proper infrastructure and services may be assessed by indicators like investment of government to realize availability of social welfare institutions [14]. The presence of shared values should be related to how citizens think about social equity and citizenship, and vulnerability is based on feelings of financial security, safety and trust in institutions and fellow citizens [26].

The objective of this study is to investigate whether citizens in resilient societies, i.e. societies which have created institutions and means to secure education, health care, and social protection and whose citizens share values and feelings on social cohesion (equity, trust, safety and regulations), become older and when old are more satisfied with life as compared to citizens in less resilient societies. A happy old population may be seen as a major challenge worldwide. The hypothesis to be tested is citizens in resilient countries have a higher life expectancy and a higher overall life satisfaction, when old, as compared to citizens in less resilient countries.

Methods

Reagents

The hypothesis is tested based on a data set of 25, well defined European societies, i.e. European nations/countries. All data used in this study are collected in 2016 and available through the data set of Eurostat [27] and the European Social Survey [28]. Almost all indicators are available from 25 countries. The mean score of all countries is used in the few cases an indicator of a country is missing. SPSS 23 is used for analysis. To test the hypotheses, three methodological steps are needed.

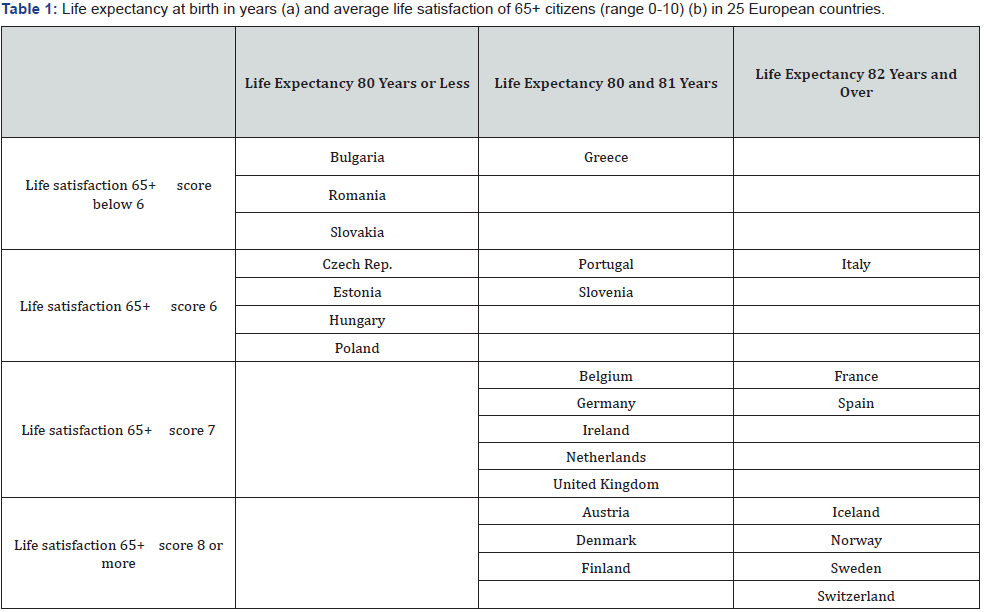

Firstly, societies/countries are classified to the extent their citizens become more or less old and are more or less satisfied with life when old. Life expectancy at birth (LE) and overall satisfaction with life (SwL) are used as indicators to assess in which countries people reach old age and high satisfaction with life, when old. LE is assessed using Eurostat data [29]. LE is defined as the mean number of years a person will live given the current mortality conditions. SwL is based on data of Eurostat, which assess satisfaction with life as a whole on a scale of 1=very dissatisfied at all to 10=very satisfied [30]. Overall satisfaction with life of citizens 65 years and over (SwL 65+) is chosen instead of SwL for all ages, because the objective is to investigate how satisfied old citizens are with life overall. As mentioned, in some country’s citizens become older than in other countries and in some countries old citizens are more satisfied with life as compared to younger citizens, but in other countries it is reverse. An overview is presented which classifies each country on overall satisfaction with life of citizens 65 years and over and on life expectancy of all citizens (Table 1). For testing the hypothesis by linear regression analysis, the scores on satisfaction with life and on life expectancy are combined in one score, assessing ‘happy old’. (Table 1)

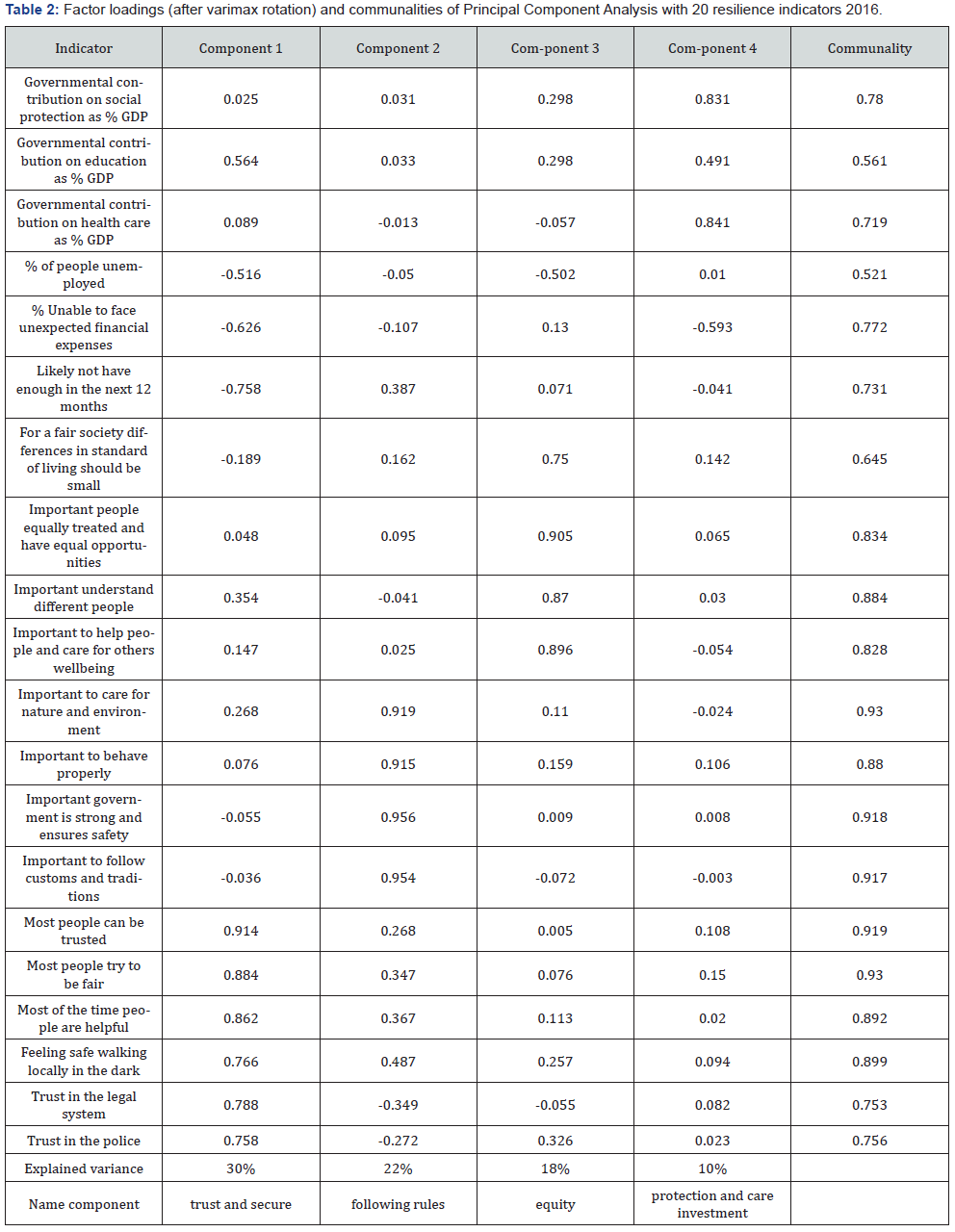

Secondly, indicators have to be identified to assess the resilience of countries, which indicators have to be checked on their coherence. Based on the mentioned literature on resilience, its definition and components, mentioned in the introduction, 20 indicators are selected from data sets of Eurostat [27] and the European Social Survey [28]. Indicators to assess the investments of the state in social security, education and health care are the % of the Gross Domestic Product which a country spend on education, health care, and social security. These indicators - also used for assessment of institutional provisions - are based on the Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG) as used in EU statistics. They present the expenditure of the general government devoted to social protection, education and health care. Shared values as indication for social cohesion are assessed by questions about equity and social helpfulness on the one hand and by questions about trust and following social rules on the other hand. The extent to which citizens may feel vulnerability or not protected is also based on feelings of trust as well as on feelings of safety and financial concerns. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) is used to test the coherence of the selected indicators to assess its components. Criteria to determine the coherence of the indicators by PCA are explained variance > 60%, communality > .50, and varimax rotated factor loadings >.50.

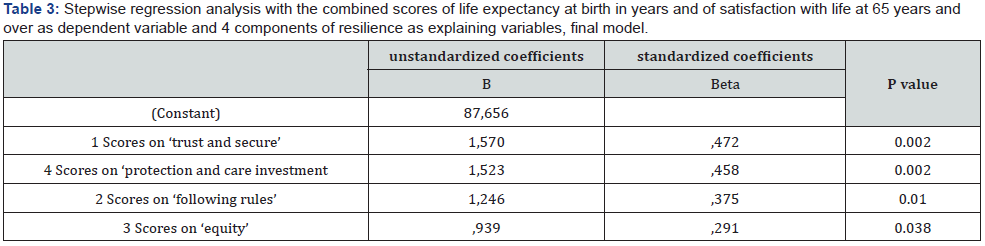

Thirdly, the relationship between ‘happy old’ (the combined SwL65+ and LE scores) and the resilience components, constructed through PCA, has to be determined. Factor scores of each PCA component are calculated for each country, which together assess the degree of resilience in each country/society. Stepwise, linear regression analysis, checking for multicollinearity, determines the relationship between the components of resilience and ‘happy old’ (LE and SwL65+). Statistically significance is defined at p<.05.

Results

In 2016 the difference in LE of citizens between the 25 European countries varies from 83.7 years in Switzerland to 74.9 years in Bulgaria. In the same year SwL65+ in the 25 countries varies between 8.4 (Denmark) and 4.9 (Greece). Both outcome variables are statistically significant correlated (Pearson’s r=.658; p<.001) (Table 1). PCA identifies 4 components with an explained variance of 80%, which meet the set criteria (Table 2). Component 1 assesses the extent of trust in fellow citizens as well as in legal institutions. Citizens scoring high on this component do not (need to) worry about financial problems and feel safe. The component is called ‘trust and secure’. (Table 2)

Component 2 indicates how important specific rules and values are (like to behave properly and to follow traditions and habits), which are also related to the importance of a strong government. This component is called ‘following rules. Component 3 identifies citizens, who state it is important to take care for each other, being equally treated, having equal opportunities and to understand different people. Also, these citizens believe that small differences in standards of living are needed for a fair society. This component is called ‘equity’. The fourth component indicates, which investments (as % of GDP) governments do in health care, social protection and education. This component is called ‘social protection and care investment’.

Stepwise regression analysis, analyzing the relationship of the four components of resilience and ‘happy old’ (LE and SwL65+ combined), shows, that all 4 components have a statistically significant contribution in explaining ‘happy old’ (Table 3). The explained variance is 59%. Scores on ‘trust and secure’ and ‘social protection and care investment’ contribute most to explain ‘happy old’, followed by scores on ‘following rules’ and ‘equity’. (Table 3)

In countries, where citizens indicate they have trust in institutions and fellow citizens and feel secure, where governments invest in social protection and health care, where citizens state it is important to follow rules, and where citizens believe in equity, in these countries citizens become older and are - when old - more satisfied with life. Citizens become less old and are less satisfied with life, when old, if they live in countries where there is less trust in institutions and fellow citizens, less governmental investment in social security and health care, where citizens believe it is not so important to follow rules, neither to help each other nor to be equally treated.

Discussion

This study shows, that citizens living in resilient societies become more often happy old as compared to citizens living in less resilient societies, at least in Europe. For example, satisfaction with life among old people in Bulgaria, Romania and Slovakia is relatively low as compared to other countries and lower than satisfaction with life among younger citizens in these countries, while also life expectancy in these countries is relatively low. Old citizens in Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland are more satisfied with life than younger people, and their life expectancy is high. The hypothesis that social resilience is related to ‘happy old’, is evidently confirmed in this study. Resilience may be seen as an important concept for policy measures to protect communities against major changes as well as citizens against risks through life span, as has been recognized by various international organizations in the last decade [15,18]. The outcomes indicate what type of policy measures will contribute to a ‘happy old society’. These outcomes and the used indicators may not only be applied to nations/countries, but also to regional and local communities as well to institutions like homes for the aged.

Nevertheless, it has to be noticed that assessing resilience is still a matter of scientific dispute, because it is applied in various disciplines, so it has various definitions and it is supposed to contain various components. Therefore, the reliability and coherence of assessing resilience through the 20 selected indicators had to be tested. A strong finding in this study is that PCA identified four, clearly distinguished components with a high explained variance, which confirm the theoretical background of the concept. These components are in line with indicators used by OECD/EU [6] and may be helpful for future studies to assess resilience in societies.

This study is one of the first, which uses resilience in studying successful ageing as was advised [10,11,17], and the assessment of resilience is operationalized based on systematic reviews [12,18,24,25]. The study shows, that becoming old and being happy old is possible and actually happening in societies characterized by trust in institutions and fellow citizens, by feelings of security and beliefs that equity, helping each other and following rules are important, and by governments investing in social protection, education and health care. The role of health care expenses may however be questioned. There is no causal link – as suggested in some studies [31,32] - between health care expenditures and life expectancy or healthy ageing. Indeed, longevity is found to be statistically related to wealth at individual and national level and life satisfaction maybe constrained by financial resources at individual level as well as national level. However, research shows, that not money in itself, but the way in which money is spent determines the relationship with longevity and satisfaction with life [33,34]. To realize high life expectancy of citizens, policy measures have to be directed on investment in social protection, on improving infrastructure, and on promot ing healthy lifestyles [35]. Such measures not only contribute to life expectancy, but also to quality of life of citizens, especially of older citizens.

This study opens new perspectives. Rather than worrying about costs of ageing, about pensions, growing medical needs and dependency, policy should focus on measures which strengthen community life, which ‘resonates a wide array of stakeholders’ [16]. And in such communities, older people are not ‘the problem’, but a ‘valuable resource’ [23]. Policy measures to realize resilient societies require reliable public sector institutions, which enables resilient components like welfare, security, social cohesion and justice. And realizing these components needs an integrated approach [11,14]. The findings of this study do not only apply to national policy measures, but also may be effective in local communities.

References

- European Quality of Life Survey (2016) Eurofound.

- Angelini V, Cavapozzi D, Corazzini L, Paccagnella O (2012) Age, Health and Life Satisfaction Among Older Europeans. Soc Indic Res 105(2): 293-308.

- Olaroiu M, Alexa ID, Heuvel WJA van den (2017) Do Changes in Welfare and Health Policy Affect Life Satisfaction of Older Citizens in Europe? Current Gerontol Geriatr Res pp. 9.

- Sander M, Oxlund B, Jespersen A, Krasnik A, Mortensen EL, et al. (2015) The challenges of human population ageing. Age Ageing 44(2): 185-187.

- Implications-ageing-examined-new-European commission.

- OECD/EU (2018) Health at a Glance: Europe. State of health in the EU cycle OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Hodder Arnold, Sander M, Oxlund B, Jespersen et al. (2015) Harper S. Ageing societies: myths, challenges and opportunities. 2006 London: The challenges of human population ageing. Age and Ageing 44(2): 185-187.

- Bloom DE, Chatterji, Kowal P, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Mc Kee M et al. (2015) Macroeconomic implications of population ageing and selected policy responses. Lancet 385(9968): 649-657.

- Graycar A (2018) Policy design for an ageing population, Policy Design and Practice 1(1): 63-78.

- Cosco TD, Howse K, Brayne C (2017) Healthy ageing, resilience and wellbeing. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 26(6): 579-583.

- Heuvel WJA van den, Olaroiu M (2019) Determinants of healthy ageing in European countries. Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine 4(5): pp. 1-6.

- Quinlan AE, Berbes-Blazquez M, Haider LJ, Peterson GD (2016) Measuring and assessing resilience: broadening understanding through multiple disciplinary perspectives. Journal of Applied Ecology 53(3): 677-687.

- UNDRR in the UN System

- Cho A, Willis S, Stewart-Weeks (2011) The Resilient Society Innovation, Productivity, and the Art and Practice of Connectedness. White Paper CISCO San Jose CA USA 8-11.

- Revilla JC, Martin P, Castro C (2017) The reconstruction of resilience as a social and collective phenomenon: poverty and coping capacity during the economic crisis European Societies20(1): 89-110.

- Wulff K, Donato D, Lurie N (2015) What is health resilience and how can we build it? Annu Rev Public Health 36: 361-374.

- Cosco TD, Kaushal A, Cooper R, Richards M, Hardy R, et al. (2015) The operationalisation of resilience in ageing: a systematic review. The Lancet 386: S32.

- Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J (2011) A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 9: 8.

- Zeng Y, Shen K (2010) Resilience significantly contributes to exceptional longevity. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res pp. 9.

- Cohen O, Geva D, Lahad M, Bolotin A, Leykin D, et al. (2016) Community Resilience throughout the Lifespan – The Potential Contribution of Healthy Elders. PLoS One.

- Resilience in older age (2014) Centre for Policy on Ageing pp. 1-40.

- MacLeod S, Musich S, Hawkins K, Alsgaard K (2016) The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing 37(4): 266-272.

- Cohen O, Geva D, Lahad M, Bolotin A, Leykin D, et al. (2016) Community Resilience throughout the Lifespan – The Potential Contribution of Healthy Elders. PLoS One 11(2): e0148125.

- Serfilipp E, Raminath G (2018) Resilience measurement and conceptual frameworks: a review of the literature. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 89(4): 645-664.

- Kwasinski A, Frainor J, Wolshon B, Lavelle FM (2016) A Conceptual Framework for Assessing Resilience at the Community Scale. S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology pp. 1-53.

- Revilla JC, Martin P, Castro C (2018) The reconstruction of resilience as a social and collective phenomenon: poverty and coping capacity during the economic crisis. European Societies 20(1): 89-110.

- Aggregate for European Union without UK. Eurostat.

- Health-status-determinants data/database.

- Quality of life indicators - overall experience of life.

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Quality of life indicators –overall experience of life.

- Budhdeo S, Watkins J, Atun R, Williams C, Zeltner T, et al. (2015) Changes in government spending on healthcare and population mortality in the European union, 1995–2010: a cross-sectional ecological study. J R Soc Med 108(12): 490-498.

- Heijink R, Koolman X, Westert GP (2013) Spending more money, saving more lives? The relationship between avoidable mortality and healthcare spending in 14 countries. Eur J Health Econ 14(3): 527-538.

- Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, Shah A, Doty MD. Mirror, mirror 2017: International comparison reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health care. The Commonwealth Fund 2017, commonwealthfund.org.

- Quality_of_life_indicators Eurostat European Commission.

- Heuvel WJA van den, Olaroiu M (2017) How important are health care expenditures for life expectancy? A comparative, European analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18(3): 276e9-276.e12.