Determinants of Healthy Ageing in European countries

Wim JA van den Heuvel1* and Marinela Olaroiu2

1 Share Research Institute, University Medical Centre, Netherlands

2Foundation Research and Advice in Care for Elderly (RACE), Heggerweg 2a, Netherlands

Submission: January 24, 2019; Published: February 26, 2019

*Corresponding author: Wim JA van den Heuvel, Share Research Institute, University Medical Centre, Netherlands

How to cite this article: Wim JA van den Heuvel, Marinela Olaroiu. Determinants of Healthy Ageing in European countries. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 002 2019; 4(5): 555649. DO 10.19080/OAJGGM.2019.04.555649

Abstract

Background and Objectives: The concept of healthy ageing is still at debate, although healthy ageing is recognized as an important policy objective internationally. Evidence of which determinants or policies at country level may affect healthy ageing is lacking. This study explores the relationship between vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience, and healthy ageing in 31 European countries. Vulnerability at national level indicates the proportion of citizens at risk for poverty and access to services. Social cohesion at national level describes the extent to which citizens are willing to accept each other. Resilience at national level includes national resources for citizens, which may support them to overcome adverse events.

Research Design and Methods: This comparative study includes data from 2013 or 2014, based on validated, comparable international data sets, i.e. Eurostat and European Social Survey. Healthy ageing describes how many years a person is expected to live in good perceived health. Healthy ageing combines life expectancy with self-perceived health. Vulnerability, social cohesion and resilience are assessed using 10 indicators, selected from the mentioned data sets. Principal Component Analysis confirms these three components.

Results: Mean healthy ageing in the 31 European countries is 72.9 years; the difference between lowest and highest is over 15 years. Multiple correlation between the 3 components and healthy ageing explains 71% of the variance. Regression analysis shows a significant contribution of resilience and vulnerability as determinants of healthy ageing.

Discussion and Implications: Vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience are interconnected and relevant determinants of healthy ageing, which indicates that an integrated approach is needed to realize healthy ageing. However, this finding question those policies, which are specifically targeted at older citizens. Resilience, assessed as investments in social security, education and health care by national governments, affects healthy ageing most. The conclusion is that a life span based, integrated policy, directed at resilience, vulnerability and social cohesion at national level, contributes to realize healthy ageing.

Keywords: Healthy ageing Vulnerability Social cohesion, Resilience.

Introduction

Healthy ageing has been recognized as a priority policy objective in various countries, stimulated by reports of the European Union (EU) and the World Health Organization (WHO), with the objective to promote healthy ageing [1-3].The concept ‘healthy ageing’ is however still a matter of debate [3-5]. It is evident that a long life itself, i.e. a high life expectancy, is an insufficient indicator for healthy ageing. Various authors notice that the concept of healthy ageing seems similar to successful or active ageing [5-8]. Basically, three methods to assess healthy ageing have been developed in the last decade all using life expectancy (at birth) as starting point: disability-free life expectancy, based on self-reported limitations in daily activities, self-related health life expectancy, based on self-perceived health, and disease-free life expectancy , based on the absence of specific diseases [9-12]. Assessment of healthy ageing, based on self-reports, is affected by social and cultural factors, whilelife expectancy itself is based on the estimation, i.e. the average number of years a person is expected to life based on the current mortality

Choosing for one method or another makes some differences. European data on life expectancy and ‘healthy ageing life expectancy’ show, that in 2014 ‘life expectancy at birth’ was 82 years, ‘self-rated healthy age life expectancy’ was 73 years, and ‘healthy life expectancy without disabilities’ was 62 years [11,13]. Besides the discussion about the concept, policy makers, researchers and health care workers look for determinants, which may influence ‘healthy ageing’ [2,3,14,15]. Determinants of healthy ageing are found at individual level (health status, activity, resilience, social contacts, involvement) as well as at environmental/societal level (provisions for accessibility, housing, age-friendly communities, social security).

Researchers as well as policy documents formulate recommendations and proposals for (public health) interventions to promote healthy ageing [3,16,17]. The question is raised whether such recommendations are tailored to the needs of older adults [18]. Whatever policy or intervention is recommended, empirical evidence to show the effectiveness of such policy or intervention, is absent. This may not be surprising, because the discussion about concept and assessment of healthy ageing hinders ‘the creation of a comprehensive public health policy’ [8]. Policies and interventions to realize healthy ageing need a clear, operational definition of ‘healthy ageing’, when looking for its determinants. By analyzing the determinants per operational definition, it will be possible to identify the main determinants of healthy ageing and to recommend effective policy measures. Our study aims to identify determinants of healthy ageing in European countries at national (policy) level. To realize the objective of this study, it is necessary to define and assess healthy ageing and to choose determinants at national/societal level, which could be relevant for ‘healthy ageing’ and to ensure these determinants should be reliable and comparable internationally

The EU describes healthy ageing as “the process of optimizing opportunities for physical, social and mental health to enable older people to take an active part in society without discrimination and to enjoy an independent, good quality of life”[2]. The WHO defines healthy ageing as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age” [3]. Two components are important in these definitions: active participation respectively functional ability, and quality of life respectively wellbeing. Although significant correlations between the two components are found, the U-shape between age and wellbeing questions a causal relationship between functional ability and well-being [19,20]. The description in the EU and WHO definitions as ‘the process’ suggests change and continuity. Indeed, healthy ageing is primarily about accepting changes in life and (therefore) changing aspirations of life [19]. Healthy ageing is part of a life-long process of learning from and responding to challenges and adverse events [21]. This process of coping with challenges and adverse events is influenced by individual capacities as well as by environmental, societal possibilities and limitations. In this study healthy ageing describes how many years a person is expected to live in good perceived health, a measure used in European statistics which combines life expectancy with self-rated health [11].

Determinants, formulated in policy documents, include available/accessible proper (health and social security) services, sustainable pension system, healthy life style, and social participation/cohesion [3]. The EU documents mention determinants, which may influence healthy age directly or indirectly: access to health care, rural/urban/physical environment, transport and infra-structure, employment and working conditions, housing, education, social issues, pensions, poverty, justice, and violence and abuse [2]. Key steps to promotehealthy ageing are accordingly WHO [3]: active participation of older persons, no age discrimination, and access to public services for older persons. These steps are specifically focusing on the older population.

Only a few studies are analyzing empirically the relationships between determinants at national level and healthy ageing. These studies show various factors to be related with healthy age: well-being, material resources, socioeconomic status, life style, social involvement and participation, and (by definition) self-rated health [6,8,22-26]. Research looking for individual determinants of healthy ageing focuses on concepts as frailty, resilience, and social capital [15,16,25,27-30], which concepts need to be translated to societal/national indicators to answer our research question.

Sadana et al. [26] develop a framework in which contextual systems (i.e. health and social care, physical environment, and social, political and economic context) influence healthy ageing directly as well as indirectly through the vulnerability/strength of citizens (lifestyle, culture and environmental risk factors). Cosco et al. [15] state, that greater resilience can be possible fostered at a population level and that there is a great potential to increase social and environmental resources through public policy interventions. They suggest, that resilience should be used as a public health concept and interventions, directed at greater resilience, which might increase resources available to older people. Based on the above-mentioned formulated determinants and research [2,3,21,26,29,30] three concepts seem predominant determinants of healthy ageing, i.e. vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience. We explore the hypothesis - using comparative data from European countries - that healthy ageing is related to vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience at national level. Vulnerability at national level is defined as the proportion of citizens at risk for poverty and access to services. By social cohesion at national level we mean the extent to which citizens are willing to accept each other. Resilience at national level describes national resources for citizens, which support them to overcome adverse events.

Methods

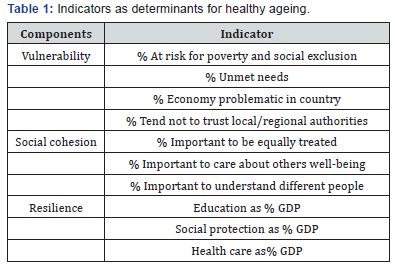

We inventoried which indicators are assessing (aspects of) vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience in international, comparative data sets, i.e. Eurostat [11] and European Social Survey [31], given the description of the three concepts above. For example, an indicator for vulnerability could be to which extent is the population in a country is at risk for poverty; or in de case of resilience: to which extent do people have excess to social security and health care provisions. The inventory for indicators resulted in 10 indicators (Table 1). The indicators are calculated as the % of expenditures of GDP on specific provisions or as % of people, which report on specific problems or believes per country.

Assessment of healthy ageing and the indicators includes 31 European countries. If data are derived from ESS, design weights are applied as required. In case of missing data of an indicator in a country, which occurred once or twice in two countries, the mean score of the remaining countries is used. Vulnerability indicators include: % people per country, who are at risk for poverty and social exclusion, who report unmet (health care) needs, who consider the economic development in the country problematic, and who tend to have no trust in local/regional authorities. Social cohesion indicators are: % of people who consider it to be (very) important to be equally treated, to care for each other’s wellbeing, and to understand different people. Indicators for resilience are: governmental expenditures oneducation, on social protection, and on health care as% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Table 1).

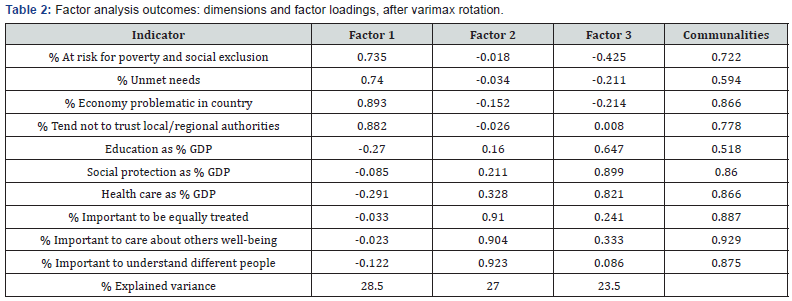

The coherence between the indicators is explored by principal component analysis (PCA) with the criteria eigenvalue 1.0, communalities >50, and varimax rotation. Factor scores are calculated for each component per country. Linear regression analysis between healthy age and the three components is executed to analyze the statistically significant contribution of these components to healthy ageing, tested for collinearity. Factor scores are tripartite divided (high, medium, low), and based on this division, clusters of countries are presented showing the connection between the assessed components and healthy ageing per country.

results

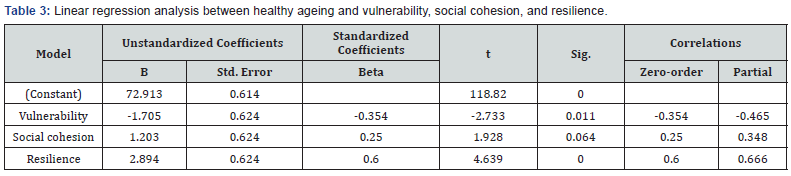

Healthy ageing between the 31 European countries vary from 64.7 years (Lithuania, number 31) to 80.3 years (Switzerland, number 1). The mean healthy ageing is 72.9 years. Three components are identified as supposed by PCA: vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience, explaining 79% of the variance. Communalities of each indicator are above > 500 and factor loadings above > 600 (Table 2). The indicators fit well in the supposed components. Regression analysis between healthy ageing and the three components (using factor scores) explains 50% of the variance (adjusted score). Vulnerability and resilience are statistically significant (p= .011 respectively p=.000), social cohesion has a p-value of .064 (Table 3).

If in a country many citizens are vulnerable, i.e. they have a high risk for poverty and social exclusion, report frequently unmet needs, consider the economic situation in their country as problematic, and they tend not to trust local/regional authorities, citizens in these countries have a low healthy ageing score. Citizens in countries, which governments spend a relatively high % of their GDP to education, social protection, and health care show a relatively high healthy ageing score. The multiple correlation between ‘healthy age’ and the 3 concepts explains 71 % of the variance.

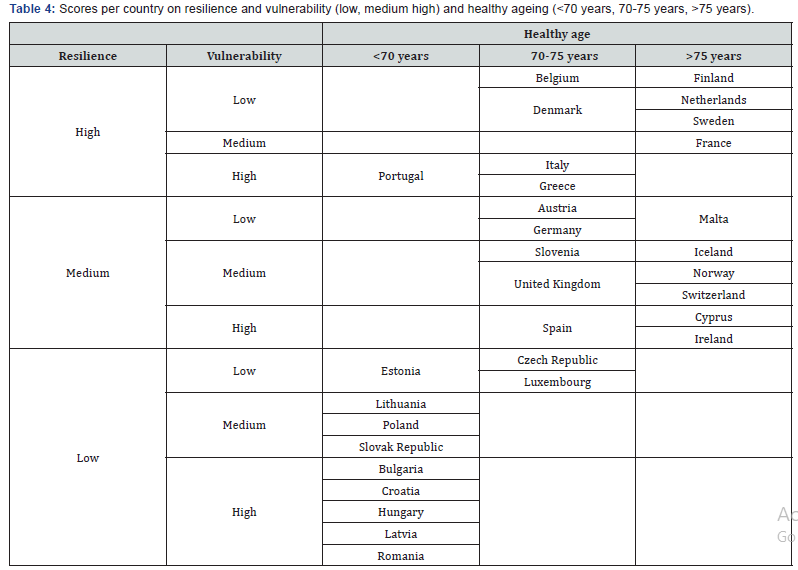

Based on these findings, the 31 European countries are clustered by resilience and vulnerability scores (Table 4). A cluster of ‘high healthy ageing’ countries, includes the countries with a preponderant positive score on resilience and vulnerability. These countries are Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, and Sweden. On the other site are countries with a low scoreon resilience and a high one on vulnerability: Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia, and Romania, which countries score on healthy ageing is below 70 years. Globally, three clusters of countries may be distinguished. A ‘north-west European’ cluster with high healthy aging countries to which besides Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, and Sweden also belong Austria, Germany, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. Citizens in these countries are ‘ageing healthy’ and these countries have national resilience provisions and their citizens have a low to medium vulnerability score. Another cluster of countries with a ‘moderate healthy ageing’ looks like a Mediterranean one with Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain. A third cluster with ‘low healthy ageing’ is concentrated in Eastern Europe with Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovak Republic, and Romania. These countries have low scores on resilience and a medium to high vulnerability

Discussion and Implications

Despite recommendations in international policy documents [2,3], it is not evident how to reach healthy ageing in societies. Therefore, we explore which determinants are related to ‘healthy ageing’ societies, by using vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience, assessed at country level, as determinants of healthy ageing. Principal Components Analysis shows, that the 3 components are reliable and comparative determinants at national level - at least in European countries - related to healthy ageing. It means, that using these determinants for policy measures and interventions are effective to promote healthy ageing. The relationship between the three determinantsindicates that an integrated approach is needed to realize healthy ageing. The outcome of this study supports our hypothesis. The determinants vulnerability, social cohesion, and resilience may easily be formulated as policy objectives. Resilience for example is realized by investments in education, social protection and health care together by governments, which are governmental functions.

These investments present total governmental expenditure devoted to three different socio-economic functions (according to the Classification of the Functions of Government - COFOG), expressed as a ratio to GDP. The COFOG divisions covered are ‘health’, ‘education’ and ‘social protection’. Such investments create a ‘enabling environment’, i.e. opportunities for resilience for citizens, which stimulate healthy ageing. These investments are not about the absolute amount of money invested, but about the percentage of GDP. It means, that if lower income countries would invest a same percentage of their GDP in these determinants as higher income countries do, they could get a same outcome: a healthy ageing population. Or as the OECD states: it is about investment in human and social capital [32]. So, it is not the amount of money itself, which counts, but the processes, which are stimulated through the investments in education, social protection and health care. These investments ensure human and social communities, in which citizens a reach high, healthy age as the final award of all investments. In that way our results support some conclusions of the OECD [32] and the WHO [3] indirectly, i.e. an integral approach is essential and ageing of a population does not necessarily mean exorbitant increases in national (curative) health budgets [13].

The statement of Cosco et al. [15], that greater resilience can be possible fostered by interventions at a population and may have beneficial effects, is supported by our outcomes. Empirically, resilience is the most important determinant related to healthy ageing at national level. Resilience also affects feelings of vulnerability of citizens, and vulnerability itself also affect healthy ageing. Social cohesion does not independently contribute to healthy ageing. But social cohesion is often seen as a prerequisite or a result of a ‘resilience policy’. Social cohesion is part of a process of integrated policy: if people believe it is important to be treated equally and to take care for each other’s wellbeing, they will support policies which ensure social security and access to social and health care facilities on the one hand and will feel less vulnerable on the other hand.

Our research outcomes question mark, whether governments should design policies specifically targeted to older persons to promote ‘healthy age’, as WHO suggests [3]. The outcomes indicate, that policies should be directed at the total population, i.e. education, social protection, safety, and accessibility. Besides, focusing on older citizens does not look as an integral approach and it may affect intergenerational solidarity, so generate societal tensions or conflicts and so inequity [33]. Healthy ageing starts at birth and needs a ‘safe environment’ life-long. A problem in research on healthy ageing - and so in this study - is the stillongoing debate on what ‘healthy age’ means. We have chosen for a concept of healthy ageing, which starts with ‘do people themselves feel healthy?’. Starting with the health perception of people themselves does not exclude at forehand people with (long-term) chronic conditions or people with disabilities, which - we believe - would be unjustified. Our definition fits in what is called a ‘new definition of health’, which describes health as the ability to adapt to physical limitations and to adjust aspirations [19,34]. Nevertheless, research in determinants of other operationalized concepts of healthy ageing is needed to confirm the significance of various determinants

Another problem when executing international, comparative research concerns methodological problems. Some of these have to be mentioned as possible shortcomings in this study. One is the absence of internationally accepted standards on how to assess concepts like vulnerability, societal risks, social cohesion, social capital, or resilience [32]. So, some concepts are not all well-defined and/or validated yet. It would be preferable if internationally validated, accepted and applied instruments are available, i.e. a validated set of ‘human development indicators’ [35]. At the same time, a strength of this study includes the data we could use. They are based on international, comparable data and collected with standardized instruments and in representative populations [10,11,31]. This ensures the reliability and comparability of our outcomes. The coherence of the indicators as tested by Principal Component Analysis indicates, that the constructs of the concepts are valid.

Conclusion

Two determinants are strongly related to healthy ageing societies: resilience and vulnerability. Based on the data of 31 European countries we conclude, that healthy ageing may be reached by governmental investments in ‘resilience’ (provisions for education, health care, and social security) and in preventing vulnerability in populations. If policy measures are implemented to do so, in such societies people may become old and also feel healthy. The interconnectedness between healthy ageing and the used concepts underlines the need for an integral policy. It is not money itself, but the way money is invested which makes healthy ageing societies.

Conflict of Interest

There was no conflict of interest that might influence the results or interpretation of the results.

References

- Healthy Ageing (2012) A Challenge for Europe. Report of the Swedish National Institute of Public Health, Stockholm, 2007,

- EuroHealthNet, Healthy and active ageing, Report, Brussels.

- WHO (2015) World report on ageing and health, Geneva, 2015, WHO? WHO Geneva, Switzerland.

- Fuchs J, Schiedt-Nave C, Hinrichs T, Mergenthaler A, Stein J, et al. (2013) Indicators for Healthy Ageing - a debate. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10(12): 6630-6644.

- Lu W, Pikhart H, Sacker A (2018) Domains and measurement of healthy aging in epidemiological studies: a review. The Gerontologist.

- Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan B, Brayne C (2014) Operational definitions of successful aging: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics 26(3): 373-381.

- Manasatchakun P, Chotiga P, Hochwälder J, Rozberg A, Sandborgh M, et al. (2016) Factors Associated with Healthy Aging among Older Persons in Northeastern Thailand. J Cross Cult Gerontol 31(4): 369-384.

- Sowa A, Tobiasz AB, Topor-Madry R, Poscia A, Ignazio MD (2016) Predictors of healthy ageing: public health policy targets. BMC Health Services Research 16(Suppl 5): 289.

- Jagger C (2007) Interpreting Health Expectancies Report. EHEMU Technical report Montpellier.

- OECD/EU (2016) Health at a Glance: Europe 2018 - State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD, Paris.

- http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics -explained

- Rappange DR, Exel J van, Brouwer WBF (2017) A short note on measuring subjective life expectancy: survival probabilities versus point estimates. Eur J Health Econ 18(1): 7-12.

- Heuvel WJA van den, Olaroiu M (2017) How important are health care expenditures for life expectancy? A comparative, European analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18: 276.e9-276.e12.

- Windle G (2012) The contribution of resilience to healthy ageing. Perspectives in Public Health 132(4): 159-160.

- Cosco TD, Howse K, Brayne C (2017) Healthy ageing, resilience and wellbeing. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 26(6): 579-583.

- Zaidi A (2014) Changing the way we age: Reducing vulnerability and promoting resilience in old age. Human development Reports.

- Acosta JD, Shih RA, Chen EK, Xenakis L, Carbone EG, et al. (2018) Building Older Adults' Resilience by Bridging Public Health and Aging-in-Place Efforts. Rand Corporation.

- Shih R, Acosta J, Chen E, Carbone EG, Xenakis L, et al. (2018) Improving disaster resilience among older adults: insights from public health. Rand Corporation.

- Schwandt H (2013) Unmet aspirations as an explanation for the age U-Shape in human wellbeing. SOEPpaper No. 580, Berlin.

- Olaroiu M, Dana Alexa I, Heuvel WJA van den (2017) Do changes in welfare and health policy affect life satisfaction of older citizens in Europe? Current Gerontology and Geriatrics research.

- Wister A, Lear S, Schuumans N, MacKey D, Mitchell B, et al. (2018) Development and validation of a multi domain multi morbidity resilience index for an older population: results from the baseline Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. BMC Geriatrics 18: 170-183.

- Haveman NA, Groot LCPGM de, Staveren WIJA van (2003) Dietary quality, lifestyle factors and healthy ageing in Europe: the SENECA study. Age and Ageing 32(4): 427-434.

- Peel NA, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP (2005) Behavioral Determinants of Healthy Aging. Am J Prev Med 28(3): 298 -304.

- Waldman-LA, Haim Erez BA, Katz N (2015) Healthy aging is reflected in well-being, participation, playfulness, and cognitive-emotional functioning. Healthy Aging Research 4: 8.

- McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, et al. (2016) Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 17: 567-580.

- Sadana R, Blas E, Budhwani S, Koller T, Paraje G (2016) Healthy Ageing: raising awareness of inequalities, determinants, and what could be done to improve health equity. Gerontologist 56(S2): S178-S193.

- Coll-PL, Del Valle Gómez G, Bonilla P, Masat T, et al. Promoting social capital to alleviate loneliness and improve health among older people in Spain. Health Soc Care Community 25(1): 145-157.

- Fontes AP, Neri AL (2015) Resilience in aging: literature review. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 20(5): 1475-1495.

- Kuh D (2007) NDA preparaty network. A life course approach to healthy aging, frailty, and capability. Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences 62(7): 717-721.

- Nyqvist F, Forsman AK (Eds.) (2015) Social capital as a health resource in later life: the relevance of context. Springer.

- ESS Round 7: European Social Survey Round 7 Data (2014). Data file edition 2.1. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway - Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC.

- OECD (2001) The well-being of nations. The role of human and social capital OECD, Paris.

- (2015) 33 Heuvel WJA van den. Value reorientation and intergenerational conflicts in ageing societies. J of Med Philos 40(2): 201-220.

- Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, Horst H van der, Jadad AR, et al. (2011) How should we define health? BMJ 343: d4163.

- Human Development Report (2016) Human Development for Everyone. Report United Nations, New York.