A Long-Term Care Hospital-Based, Novel, Cost-Effective Strategy to Reduce Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections

Christina M Layman1, Roman A Jandarov2, Laura A Schuster1 and Madhuri M Sopirala3*

1Daniel Drake Center for Post-Acute Care, UC Health

2Division of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Department of Environmental Health, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, USA

Submission: February 27, 2018; Published: March 08, 2018

*Correspondence author: Madhuri M Sopirala, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, USA, Tel: 513-558-4707; Email: msopirala@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Christina M L, Roman A J, Laura A S, Madhuri M S. A Long-Term Care Hospital-Based, Novel, Cost-Effective Strategy to Reduce Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2018; 3(4): 555617. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2018.03.555617

Abstract

An innovative nurse-led initiative of central venous catheter (CVC) dressing maintenance in long-term acute care (LTAC) setting significantly reduced the organizational incidence of central line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI). The initiative included limiting scheduled CVC dressing changes to a trained staff nurse dedicated to that task. The project demonstrated that the initiative reduced patient harm by eliminating CLABSI in LTAC patients and was cost effective.

Keywords: Central line associated blood stream infections; Long-term acute care; LTAC; CLABSI; Line maintenance

Abbreviations: LTAC: Long-Term Acute Care Hospitals; LTCH: Long-Term Care Hospitals; CVCs: Central Venous Catheters; CLABSI: Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections; LOS: Length Of Stay; PICC : Peripherally Inserted Central Venous Catheters; CDC: Center for Diseases Control; NHSN: National Health Safety Network; DU: Device Utilization; CMI: Case Mix Index

Introduction

Long-term acute care hospitals (LTAC) serve clinically complex patients requiring extended medical and rehabilitative care [1]. LTAC hospitals also referred to as long-term care hospitals (LTCH), have patients with Central Venous Catheters (CVCs) akin to acute care patients for either long-term antibiotics or other chronic intravenous medications [2]. Therefore, they are at risk for Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI) resulting in significantly increased mortality, mean Length Of Stay (LOS), readmissions to acute care hospitals and mean attributable costs [3,4]. Maintenance of CVCs is ever more important in LTAC due to prolonged need for CVC to administer long term intravenous medications. However, literature is scarce in studies focusing on prevention of CLABSI in LTAC population [5-8].

Use of dedicated specialized intravenous teams has been successful in some acute care hospitals but may not be feasible or cost effective in smaller settings such as LTAC hospitals [9].9 While dressing changes are an important aspect of CVC maintenance, there are variations in technique among nurses with a potential lapse in maintenance of sterility during dressing changes [10,11]. We sought to find a feasible and cost-effective intervention customizable to LTAC hospitals that achieves desirable patient safety outcome by limiting scheduled dressing changes to dedicated personnel thereby limiting the variation in technique. To our knowledge, this is the first study to have evaluated the effect of limiting scheduled dressing changes to trained personnel other than specialized IV teams dedicated to that task in the LTAC hospitals. This is also the first study to evaluate the effect of dedicating a trained staff nurse other than specialized IV team nurses for dressing changes on CLABSI incidence in any clinical setting.

Methods

Clinical Setting and Study Design

This study performed a retrospective data analysis in an 82-bed LTAC hospital using before-and-after comparisons. Institutional Review Board has deemed this study a non-human subjects research.

Study Period

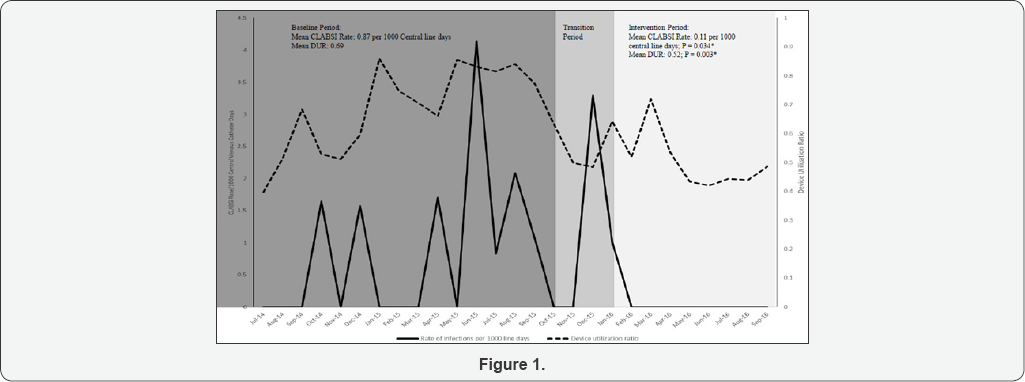

The baseline period was July 2014 to September 2015. Intervention period was January 2016 to September 2016. Transition period was October 2015 to December 2015 (when we rolled out the intervention).

Study Participants

All LTAC patients with a central catheter in place during the study period were included in the study.

Protocols During Baseline Period

Trained physicians inserted single, double or triple lumen CVCs, which are coated with chlorhexidine/silver sulfadiazine. Vascular access nurses placed peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC). All central catheter insertions used maximum sterile barrier precautions. LTAC used TegadermTM chlorhexidine gluconate dressings. Staff nurses routinely changed dressings once a week or when dressings are not occlusive, intact or dry with the exception of gauze dressings that were uncommonly used for oozing sites and were routinely changed every 48 hours. Nurses scrubbed the hub prior to any line access per CDC guidelines.9 Physicians discontinued the central lines when no longer needed. All staff nurses received catheter maintenance training at their new hire orientation and on skills days that occurred on a yearly basis.

Intervention

All baseline period protocols were also followed during intervention period. The nurse educator trained one staff nurse on dressing change technique for this intervention. The staff nurse (intervention nurse) changed dressings on a weekly basis. All staff nurses continued to be trained at their new hire orientation and on skills days. When an impromptu change was needed because of a soiled or non-occlusive dressing, the bedside nurse changed the dressing.

Outcome Measures

We used Center for Diseases Control (CDC)/National Health Safety Network (NHSN) definitions for CLABSI surveillance [3]. Outcome measures were CLABSI incidence rate per 1000 central line days and device utilization ratio. Device utilization (DU) was calculated as a ratio of device days (central line days) to patient days. The case mix index (CMI) is an economic surrogate marker used to describe the average morbidity of patients in hospitals [12]. We compared the CMI during the baseline period and intervention period to evaluate if there was a change in morbidity in the LTAC patient population during the two periods that might otherwise explain the changes in CLABSI incidence and DU.

Cost Estimates

CLABSI Costs: Costs for CLABSIs were obtained from previous research in LTAC hospital residents [4]. A mean attributable cost of $43,208 for a single CLABSI was used for cost analysis.

RN Wages/Benefits: We obtained data on RN wages from the Bureau of Labor and Statistics FY 2016. Since these wages are without benefits, we conducted additional analyses using a benefit estimate of 25.6% from previously published literature [13].

Statistical Analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.3.0.28. We used two-tailed t-tests to examine the difference in mean (± standard deviation) CLABSI rate, DU ratio and CMI between baseline and intervention groups. Statistical significance was determined at a P value of 0.05.

Results

We evaluated a total of 21,770 central line days and 35,732 patient days during the entire study period.

CLABSI Incidence Rate, Catheter Utilization and Case Mix Index

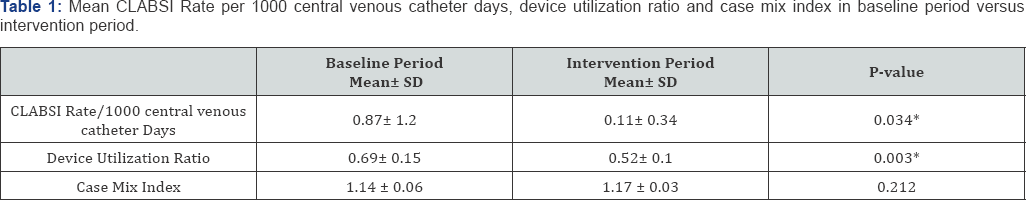

As shown in Table 1, mean CLABSI rate significantly decreased from 0.87 ± 1.2 per 1000 central line days in baseline period to 0.11 ± 0.34 per 1000 central line days (P = 0.034) in intervention period. Device (catheter) utilization ratio also decreased from 0.69 in baseline period to 0.52 in intervention period (P = 0.003) (Figure 1). There was no statistically significant difference in CMI in intervention period (1.17 ± 0.03) compared to baseline period (1.14 ± 0.06) (P = 0.21) (Table 1).

*Significant at P<0.05

SD = Standard Deviation

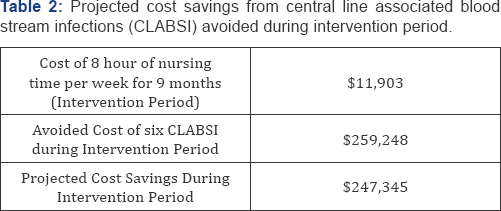

CLABSI Attributed Costs

Using the mean attributable cost for CLABSI ($43,208 per case) published in 2014 and methods previously used, we calculated the cost avoidance achieved by the intervention during the study period [13-15]. There were 15 CLABSI in baseline period of 15 months and there was one CLABSI in the intervention period. The expected number for intervention period was projected as seven CLABSI cases applying the rate from baseline period and actual central line days in intervention period. Therefore, we calculated that the number of CLABSI avoided over the intervention period as six cases with an avoided cost of $259,248. Based on data from Bureau of Labor Statistics and previously published studies, we calculated the cost of RN time involved during the intervention period as $41.33 per hour including the base wage and benefits. Calculating for 8 hours a week for the 9-month intervention period, the cost of RN time devoted to the intervention was $11,903. Therefore, we calculated the cost savings as $247,345 (Table 2).

Limitations

This study was conducted in a single LTAC hospital but we believe our findings are generalizable since our hospital is similar to most LTAC hospitals in the country. The intervention nurse did not perform impromptu dressing changes (unscheduled, as needed) and had to rely on staff nurses for those. Even though we do not have data on how many impromptu dressing changes were performed, the significant decrease in CLABSI rate during the intervention period indicates that the collective intervention was effective. The training of nursing staff has not changed between baseline and intervention periods. However, it is possible that there was increased awareness among educators (trainers) during the intervention period and that could have affected nursing performance which we are not able to measure.However, one could argue that this effect, if it occurred, was desirable though unintended. Simultaneous decrease in DUR may also have played a role in reduced CLABSI. However, we believe this decrease was also the result of increased awareness due to this intervention. We did not assess patient level data such as age and length of stay. However, we showed that there was no difference in CMI between the baseline and intervention periods.

Discussion

Literature addressing CLABSI reduction with strategies specifically applicable to LTAC hospitals is scarce. Attention to dressing maintenance is even more important in LTAC hospital setting where patients have long stays with CVC in place for prolonged durations. However, ensuring adherence can be a challenge especially with increasing patient care demands on nursing. Utilization of intravenous therapy teams dedicated to dressing maintenance has been described in acute care literature [11,16,17]. We created and validated an effective strategy that specifically addressed the challenge of limiting variability in dressing maintenance in LTAC hospitals while avoiding the burden of increased costs related to specialized IV care teams which is neither feasible nor practical in these settings.

Our study has shown that limiting scheduled dressing changes to trained staff nurse/s dedicated to that task is associated with decreased CLABSI incidence in LTAC setting. Even though our CLABSI rate during baseline period was low, we had opportunity to improve our CLABSI rate even further with this intervention. This thought process is consistent with the culture of safety which asserts that one preventable complication is one too many. We could show a clear decrease in our CLABSI incidence to near-zero in intervention period. No other processes have changed between baseline period and intervention period. It is interesting that the device utilization ratio has also decreased during the intervention period despite not having any other simultaneous intervention to reduce device utilization. We believe this was due to an increased awareness towards CLABSI prevention due to mere introduction of the study intervention.

Hiring or allotting FTE to dedicated tasks such as this may be considered a hindrance from the standpoint of cost. However, we showed that having dedicated staff for central line dressing changes is very cost effective with avoided cost of CLABSI being much higher than the RN time required to perform the intervention. A detailed business plan explaining the cost effectiveness of this approach to hospital administration may be effective in getting the needed support for such an intervention. This approach could be an alternative to having a dedicated IV team for central line maintenance when having such a team is not feasible either due to financial constraints or due to small size of the healthcare setting.

Our study has much strength. First, to our knowledge, this is the only study to have assessed the strategy of dedicating a trained staff nurse that is not part of intravenous therapy team for CVC dressing maintenance especially in LTAC hospital setting. Second, we were able to demonstrate that this approach is feasible and cost-effective. Third, this simple intervention can be easily adapted at any LTAC hospital.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated the feasibility and cost- effectiveness of limiting scheduled CVC dressing changes to trained staff nurse/s dedicated to that task in LTAC hospital setting. We showed that this approach was successful in reducing CLABSI to near-zero. This strategy should be considered in LTAC settings to reduce CLABSI.

References

- Liu K, Baseggio C, Wissoker D, Maxwell S, Haley J, et al. (2001) Longterm care hospitals under Medicare: facility-level characteristics. Health Care Financ Rev 23(2): 1-18.

- Long-term Care Hospital (LTCH), Quality Reporting Program (QRP) (2015) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site.

- Wolfenden LL, Anderson G, Veledar E, Srinivasan A (2007) Catheter- associated bloodstream infections in 2 long-term acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28(1): 105-106.

- Munoz-Price LS, Hota B, Stemer A, Weinstein RA (2009) Prevention of bloodstream infections by use of daily chlorhexidine baths for patients at a long-term acute care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 30(11): 1031-1035.

- Edwards M, Purpura J, Kochvar G (2014) Quality improvement intervention reduces episodes of long-term acute care hospital central line-associated infections. Am J Infect Control 42(7): 735-738.

- Grigonis AM, Dawson AM, Burkett M, Dylag A, Sears M, et al. (2016) Use of a Central Catheter Maintenance Bundle in Long-Term Acute Care Hospitals. Am J Crit Care 25(2): 165-172.

- Bloodstream Infection Event (Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection and non-central line-associated Bloodstream Infection) (2017) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site.

- Kaye KS, Marchaim D, Chen TY, Baures T, Anderson DJ, et al. (2014) Effect of nosocomial bloodstream infections on mortality, length of stay, and hospital costs in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(2): 306311.

- Timsit JF, Bouadma L, Ruckly S, Schwebel C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, et al. (2012) Dressing disruption is a major risk factor for catheter-related infections. Crit Care Med 40(6): 1707-1714.

- Brunelle D (2003) Impact of a dedicated infusion therapy team on the reduction of catheter-related nosocomial infections. J Infus Nurs 26(6): 362-366.

- O Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, et al. (2011) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control 39: S1-S34.

- Kuster SP, Ruef C, Bollinger AK, Ledergerber B, Hintermann A, et al. (2008) Correlation between case mix index and antibiotic use in hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 62(4): 837-842.

- Dorr DA, Horn SD, Smout RJ (2005) Cost analysis of nursing home registered nurse staffing times. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(5): 840-845.

- Cromer AL, Hutsell SO, Latham SC, Bryant KG, Wacker BB, et al. (2004) Impact of implementing a method of feedback and accountability related to contact precautions compliance. Am J Infect Control 32(8): 451-455.

- Sopirala MM, Yahle Dunbar L, Smyer J, Wellington L, Dickman J, et al. (2014) Infection control link nurse program: an interdisciplinary approach in targeting health care-acquired infection. Am J Infect Control 42(4): 353-359.

- Meier PA, Fredrickson M, Catney M, Nettleman MD (1998) Impact of a dedicated intravenous therapy team on nosocomial bloodstream infection rates. Am J Infect Control 26(4): 388-392.

- Miller JM, Goetz AM, Squier C, Muder RR (1996) Reduction in nosocomial intravenous device-related bacteremias after institution of an intravenous therapy team. J Intraven Nurs 19(2): 103-106.