Fundamental Causes in Illness and Health Behavior: A Cross-National Comparison of Young Adults in the US and Nepal

J Scott Brown1*, Janardan Subedi1, Sree Subedi1, Kelina Basnyat1 and Mark Tausig2

1Department of Sociology and Gerontology, Miami University, USA

2Department of Gerontology, University of Akron, USA

Submission: February 16, 2018; Published: February 23, 2018

*Corresponding author: J Scott Brown, Department of Sociology and Gerontology, Miami University, USA, Tel: (513) 529-8325, Email: sbrow@miamioh.edu

How to cite this article: J Scott Brown, Mark Tausig, Kelina Basnyat, Sree Subedi, Janardan Subedi et al. Fundamental Causes in Illness and Health Behavior: A Cross-National Comparison of Young Adults in the US and Nepal. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2018; 3(3): 555615. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2018.03.555615.

Abstract

Extensive research has examined the nature of stress and its relationship with social and health outcomes in industrialized nations. On the other hand, considerably less study has focused on the role of stress in the well-being of individuals living in developing nations, and almost no research has directly compared this relationship across developed and developing nations. Yet, fundamental sociological concepts, such as Durkheim's mechanical and organic solidarity, imply such an approach to fully understanding such social relationships. In this study, we compare the relationship between stress from the death of a parent and two indicators of well-being, substance use and mental health, in the United States and Nepal. Additionally, differences between urban and rural contexts are emphasized. US data come from the third wave of the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative survey of adolescents and young adults. Data from Nepal come from two sources, the Kathmandu Mental Health Survey and the Jiri Health Survey, which respectively represent urban and rural settings in this developing nation. Data from the US are consistent with most research in developed nations. Females have higher rates of depression whereas males have higher rates of substance use with stressors more strongly tied to these gendered outcomes. In Nepal, the relationship of gender and education on both being depressed and substance use is similar to that in the US. However, significant socioeconomic effects on substance use beyond education are noted in the US, whereas age plays a unique role across all outcomes in Nepal. Implications of these similarities/differences are discussed.

Introduction

More than two decades ago, Link and Phelan 1995 pointed out the emphasis on individualized health risk factors in epidemiological and social research and suggested that such focus was problematic for research and policy that aimed to equalize health disparities. Rather, they suggested that a focus on underlying social structural conditions, or "fundamental causes," of illness was necessary to ultimately understand and reduce inequality in health outcomes. Such fundamental causes, they argue, produce social and environmental contexts that lead to divergent health outcomes across a variety of diseases and disease mechanisms. Link and Phelan note that, if such underlying issues are ignored, individually-based interventions are likely to be ineffective [1]. To substantiate the veracity of the fundamental cause argument, it is necessary to demonstrate the consistency of a fundamental cause effect across a variety of social and/or temporal contexts that include a diversity of morbidity and mortality regimes and a variety of disease mechanisms behind that diversity. In Link and Phelan's 1995 original discussion, they propose socioeconomic status (SES) as a fundamental cause comparing diseases and disease mechanisms across historical contexts from the 19th through the 20th century in present-day developed nations (especially the U.S.).

The current study expands this literature in two ways. First, we explore the notion of fundamental causes comparatively by examining comparable health and health behavior measures in the U.S. and Nepal, thus exploring the fundamental cause argument across developed and developing contexts. To date, study of fundamental causes within a developing nation context has largely been ignored. Second, within Nepal, we similarly compare comparable health outcomes and health behaviors across very different urban and rural contexts, a comparison that is also scarce with the literature on fundamental causes of disease. Specifically, we compare the "fundamental" nature of SES as a causal factor associated with depression, smoking behavior, and alcohol consumption using data on young adults from the U.S., an urban (modernized) part of Nepal (Kathmandu), and a more traditional village (Jiri) in Nepal. If the fundamental cause argument holds, then the relationship between social structure (SES) and health risk should hold when comparing developed and developing societies and when comparing "modern" and traditional social life within developing countries. Indeed, given the substantial economic inequality found in the U.S. context compared to the more limited range of economic differences across statuses in the economically disadvantaged Nepali contexts (i.e., the "floor" effect of absolute poverty that affects the Nepali economic distribution across SES statuses), results consistent with fundamental cause arguments should be interpreted as significant evidence in support of this thesis.

Fundamental Causes of Disease

Since Link and Phelan's 1995 original work proposing the fundamental cause argument, a growing literature has emerged around this concept. This work has generally tested the fundamental cause argument in three ways: Further refinement of the theory itself (especially pertaining to clarifying how SES is a fundamental cause); Applying the theory across different illnesses; Applying the theory in cross-national comparisons. Much of the refinement of the fundamental cause argument has been conducted by Link, Phelan, and their colleagues [2]. This work predominantly expands on the original proposition published in the medical sociology literature and extends that argument into related fields such as public health and gerontology. Additionally, a debate regarding whether SES is truly a fundamental cause or merely part of a spurious relationship explained by intelligence as the true underlying fundamental factor in health disparities has begun [3]. Furthermore, recent work has begun to discuss the interconnections of SES with gender and race inequality within the framework of the fundamental cause thesis [4]. Notably, when this theory- building work has employed supporting empirical data analysis, such data have come almost exclusive from the U.S. context.

While work refining the fundamental cause argument has been ongoing, other research has focused on demonstrating the validity of the thesis across various diseases and other health markers. Such work has shown support for the fundamental cause thesis when looking at cancer, HIV/AIDS, cholesterol levels, and mortality [5]. Similarly, work in this area has also used almost exclusively data from the United States, though some have noted the need for more testing of the thesis across contexts with different social and economic structures.

In response to this need, a handful of studies have begun to look at the fundamental cause argument comparatively. In such work, examined the fundamental cause thesis comparing the U.S. and Iceland, observing similar, though weaker, SES effects on health in Iceland compared to the U.S [6]. The effectiveness of the more progressive welfare state in Iceland is proposed as a possible explanation for this difference. Mc Donough et al.[7] show similar findings comparing the U.S. and U.K, and also suggest that the steeper SES-to-health gradient observed in the U.S. might be due to the effects of more comprehensive social policy in the U.K. Willsons et al. [8] findings when comparing the U.S. with Canada, however, are more problematic for the fundamental cause argument. Though low SES is associated with higher odds of preventable illness in the U.S. context, the Canadian results show no SES effect. Willson suggests that these results are still consistent with the fundamental cause thesis noting that less overall SES inequality in Canada than the U.S. coupled with more comprehensive social policies could explain the lack of SES results in the Canadian context. Why such findings are much more prominent in Canada compared to the results from studies in Iceland and the U.K., however, remains to be explained.

More importantly, perhaps, this limited set of comparative work has compared the U.S. to similarly industrialized nations that are among the wealthiest nations, even among developed nations. The lack of a comparison of the fundamental cause argument between developed nations and developing nations is notable. The universal claim of the fundamental cause argument should hold across societies that are organized in radically different ways even though the social and cultural meaning of status differences varies substantially. Since the core of the fundamental cause argument is differential access to resources based on differential location within a social structure and the major difference between developed and developing countries is the absolute level of resources, it is important to evaluate exactly how universal (fundamental) this social explanation for health inequality may be in light of such differences.

Indeed, Olafsdottir's et al. [9] results in comparing Iceland and the U.S. exemplify the strengths and weaknesses of the current research literature. The comparison of similarly wealthy nations with radically different welfare state mechanisms that address social status inequalities in very different manners and with substantially varying comprehensiveness allows for a particularly effective assessment of the fundamental cause thesis by focusing on the potential effects of the magnitude of inequality. Yet, research in such developed contexts offers little variety in the actual structure of different statuses and the relationships of those statuses to larger social institutions (e.g., both Iceland and the U.S. have similar occupational groupings oriented within relatively comparable post-industrial economies). By looking at developing contexts, such as Nepal, a more extensive assessment of fundamental causes is possible given that 1) such contexts offer similarly compressed economic inequality (i.e., the absolute poverty found in such contexts mimics in many ways the compressed inequality found in nations with more comprehensive welfare states such as Iceland-that is, even the relatively more economically well off in developing contexts are often not as disparate from their less fortunate peers compared to the heightened inequality found in liberal welfare state settings such as the U.S.) and 2) that the economic system and social statuses within that system are markedly different from those found in developed nations [10,11].

At the same time, non-developed countries are, in fact, developing. They are generally making a transition from traditional, relatively simple agro-pastoral economic and "mechanical" social relationships to more industrial/postindustrial economic and interdependent social relationships. This implies that the economic and social bases that create differential access to resources may also be undergoing changes within such nations. Perhaps the clearest way this can be observed in developing countries is through the differences between rural and urban settings that typically reflect the difference between traditional social relations and ones in the process of industrializing [12].

Developed vs. Developing Nations (U.S. vs. Nepal)

The magnitude of the difference in the wealth of Nepal and the U.S. is very easy to specify. The per capita Gross Domestic Product in 2000 for Nepal was $1,224 while in the U.S. it was $34, 677. The U.S., of course, is the quintessential example of a developed country while Nepal is one of the least economically developed countries in the world. The difference in wealth between these societies is also reflected in the quality of health and in the specifics of health risks. In comparison to the United States, the health of the Nepalese is very poor [13]. Life expectancy at birth in Nepal is about 65 years compared to nearly 80 years in the U.S. Until relatively recently, Nepal was one of the few countries in the world where males outlived females, due mainly to high rates of mortality in childbirth, and even now female life expectancy exceeds male life expectancy by less than 3 years. Infant mortality in Nepal ranges from 100115 per thousand births compared to 7-9 per thousand in the U.S. Despite these statistics, the annual population growth rate in Nepal is 2.4% compared to 1.1 % in the U.S., and the fertility rate in Nepal is 4.6 compared to 2.0 in the U.S WHO, 2001 [14].

The health problems in Nepal also differ from those in developed countries. Vitamin deficiencies and micronutrient- related disorders are widespread in Nepal [15]. Groundwater and well water contamination are significant problems. Food- borne illness is also a substantial source of illness in Nepal. Meat, in particular, is a prime source of food poisoning and the acquisition of parasites.

Urban vs. Rural (Kathmandu vs. Jiri in Nepal)

Within Nepal the illness burden differs between the urbanized area of Kathmandu and rural areas such as Jiri, which retains a largely traditional social structure. In part, the difference stems from the fact that fresh water and modern medical practice are scarce in rural areas like Jiri so that many easily controlled disorders such as parasitic and bacterial infections and respiratory ailments are common in Jiri but less prevalent in Kathmandu. Urban life exposes residents to different health risks. Smith reports, for example, that Sherpas living in Kathmandu have higher blood pressure than Sherpas living in the mountains. Urban dwelling Sherpas had higher BMIs and consumed more alcohol, which accounted for the differences in blood pressure and the elevated risk of chronic illness. There is also some evidence that psychological resources vary across the urban-rural divide, but mostly for women rather than for men [16].

Social Status and Access to Resources

The relationships between social status characteristics and exposure to risk or vulnerability to experienced risk appear to hold across urban and rural settings, but there is also reason to believe that the relationships are not identical across status groups. In traditional Nepal, for example, it is extremely rare for women to become educated and/or to generate independent economic assets (i.e., hold jobs). By contrast, in urban settings it is much more likely that a woman will become educated and that she will become economically self-sufficient or at least employed for pay. Economic development, as it is manifest in many urban areas, gives previously less-advantaged groups (such as women) better access to resources and, by the fundamental cause argument, may lead to comparatively better health. Thus, while differences in access to social resources between developed and less developed countries should be reflected in health differentials, one should also expect that differences in access to social resources between urban and rural areas of Nepal will be reflected in additional health differentials [17].

Although health risks differ as a function of the relative wealth of the U.S. and Nepal, there is reason to believe that social status differences operate similarly. Socio-economic status and gender affect illness rates in Nepal. Rous, Hotchkiss [18] reported that income has a direct effect on the likelihood of becoming ill in Nepal. Low social class is also associated with early marriage, complications in childbirth and maternal mortality, and women are generally at substantial risk of birth complications because 90% of births occur without skilled medical personnel present. In the United States, health inequality is often indexed in terms of class (education and income) and race. Americans who are poor, who have low education, and who belong to African American and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups have worse health. They have higher rates of both morbidity and mortality. However, health differences by gender are also observed, particularly with regard to psychological disorders. Women report more affective disorders while men report more substance abuse disorders. Although the U.S. and Nepal differ substantially in terms of the composition of the illness burden, that burden is distributed unequally in each society based on social status (particularly gender and class).

In the following analysis we make use of three data sets with common measures across U.S. and Nepalese societies and within Nepal to test the fundamental cause argument. We expect that health risk will vary by social status characteristics in both the U.S. and Nepal. We also expect health risk to differ between the urban and non-urban communities in Nepal. Unlike the developed contexts of Canada, Iceland, and the U.K. that have been compared to the U.S. in previous work, Nepalese social welfare policies are much less comprehensive than even those of the U.S. Thus, we do not expect to find weaker SES-to-health associations previously noted, although such a finding might not be surprising given the compression of most Nepali citizens into the lower portions of that nation's economic strata.

Data and Methods

Our data come from three sources. Data from the United States are taken from the public use files for the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health is a school-based survey of health and health-related behaviors of adolescents in grades 7 through 12. The sampling frame included all high schools in the United States. A stratified, random sample from 80 clusters of schools was selected from this group. Over 90,000 students completed the in-school survey in 1994. Of those, a baseline sample of adolescents was interviewed at home between April and December 1995, between April and August 1996, and again between August 2001 and April 2002. The overall sample is representative of United States schools with respect to region of the country, urbanity, school type (e.g., public, parochial, private non-religious, military, etc.), ethnicity, and school size [19].

The Add Health data used here come from the third wave of in-home data collection in 2001-2002. Specifically, we examine the public use data which are a random sample of 50 percent of the Add Health Wave I core sample and 50 percent of the Add Health Wave I high education black sample. We restrict the analytic sample (n = 4,882) to the third data collection wave of Add Health (respondent ages 18 to 28 years) to achieve age comparability with the Nepali samples (described below). Data from Nepal come from two surveys. Urban data are taken from the Kathmandu Mental Health Survey; rural data come from the Jiri Health Survey. The target population for the Kathmandu Mental Health Survey is adults living in households in the Kathmandu, Nepal metropolitan area (this includes the municipalities of Kathmandu and Lalitpur). A preliminary list of households from the 2001 national census tabulated by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) of Nepal was obtained in June, 2001. Although a simple random sample of households could have been drawn from the list, a two stage cluster sampling procedure was adopted. Kathmandu and Lalitpur are divided into administrative units called 'Wards'. Kathmandu has 35 wards and Lalitpur has 22 wards. Considering these 57 administrative wards as 57 clusters, 20 clusters were randomly selected with replacement using a probability proportional to household numbers in the clusters. A simple random sample of 250 households were taken from each cluster (i.e., ward) selected at the first stage. This resulted in 5000 households in the sample from 16 wards.

As the study was in progress, it was discovered that the sampling frame was faulty. It listed either more households or fewer households in certain wards than were actually present. In addition, about 10,000 households were missed by the CBS in its initial listing. This resulted in fewer households available for interview in certain wards reducing the total sample size obtained. Adjustments to data collection were made by repeating the process of randomly selecting wards but only using those ward numbers that were not selected with the faulty frame. Six new clusters (wards) from the new frame were chosen, and 250 households were chosen randomly from each drawing of a cluster. This process restored the sample to 5000 households. To reach age comparability with Wave III of the Add Health sample, data were reduced to only persons aged 18 to 29 years, resulting in an analytic sample of 1,052 respondents [20].

Data for the Jiri Health Survey were collected during a larger study of genetic risk factors for helminthic infection among the population of the Jiri Valley, in Eastern Nepal. The Jiri valley consists of a total of nine villages in the Dolakha District of Nepal. The region is 190 kilometers east of the capital city of Kathmandu. In general, the Jirels are subsistence farmers whose domestic economy is based on agro-pastoral production. The villages of Jiri have access to electricity and tap water, and a few houses have radios and television sets as well. All households in the area are listed in the project registry for the genetic risk factors health study. A simple random sample of 221 households (one in three) with approximately 1500 residents was drawn from the registry for this study. All individuals 18 years of age and above in these households were then enumerated and interviews were collected (n=426). To reach age comparability with Wave III of the Add Health sample, data were reduced to only persons aged 18 to 29 years, resulting in an analytic sample of about one-fifth of respondents (n=86) [21].

Measures

As in any comparative study, obtaining comparable measures across surveys and across national contexts is a difficult issue. When comparative work includes developing context, this task becomes even more problematic, and when rural contexts within a developing nation are examined, as in the current study, comparability of measures is nearly impossible. For the data used here, however, some comparable measures are available. Nevertheless, in order to examine the question of fundamental causes across these very diverse contexts, it has been necessary to adopt two compromising strategies. First, when possible, highly detailed measures in one or two of the datasets have been re-coded to match the lowest common component of that measure across all three surveys. Second, rather than focusing on a single health outcome with multiple SES predictors and control measures, the current study examines multiple health- related outcomes with a more limited set of predictors [22].

Depression

In the Jiri sample, only a dichotomous measure of whether a respondent has ever been depressed was collected. While the Kathmandu sample has somewhat more extensive measurement of depressive symptoms, we limit our measure here to a dichotomous measure of whether the respondent felt depressed 'most' or 'all' of the time over the last 30 days to maintain comparability with the Jiri data. Wave III of Add Health includes a balanced 10-item variant of the CES-D that has been shown to be consistent across gender. However, consistency across different ethnic groups for this scale is not well established which imply problematic application for cross-cultural comparisons. Such inconsistencies in the full scale across racial/ethnic groups have also been noted, but this research has shown that the depressed affect subscale within the CES-D is invariant across different ethnic groups within the US. We therefore use the four depressed affect scale items that are included in Wave III of Add health by summing them to create a 4-item scale (Individual items are coded on a three-point scale, from never or rarely (1) to most or all of the time (3) and refer to feelings the respondent had in the past week; scale values range from 0 to 16) and use a cutoff of 4 or more symptoms to create a dichotomous measure of being depressed to maintain a rough equivalence with the simpler measure available in the Jiri sample [23,24].

Smoking

Smoking in both the Jiri and Kathmandu samples is measured using a question that asks the respondent to identify themselves as 'never smoked', 'ex-smoker', or 'current smoker'. A dichotomous measure is created from these categories to indicate if the respondent ever smoked in order to achieve comparability with the U.S. data. In Add Health, respondents are asked whether they have ever smoked regularly at any point in their life for a period of at least 30 days [25].

Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption is measured using an almost identical question across all three surveys that ask how frequently the respondent drank over the last 12 months. Responses are recoded into heavy drinkers (those who drank 3 days a week or more) with non-drinkers and those who drank on fewer than 3 days per week being the reference group [26].

SES

Education is measured as a dichotomous indicator of whether or not an individual has 12 or more years of education. Income status is measured as a dichotomous measure for high versus low income. An advantage in using the Nepali data for the purposes of the current study comes from the fact that income data have been adapted to U.S. dollar equivalents. That is equivalent currency is calculated in terms of value and not as a direct conversion of dollar to rupees in the survey documentation. For the U.S. data, we define low income as less than $12,000 per year to ensure that this category represents an income level at or near the poverty line. The equivalence data provided in the Kathmandu data documentation shows this to be equivalent to less than 60,000 rupees per year (i.e., 60,000 rupees per year is equivalent to about $12,000 a year in the context of Kathmandu, though the actual conversion rate would give a value of just under $900 U.S.). Because the rural areas of Nepal, like the Jiri area examined in the current study, are subject to substantially lower economic standards of living compared to the urban capital of Kathmandu, we use a suitably lower income threshold to indicate a near poverty level of less than 12,000 rupees per year.

Control Measures

Control measures include age, gender, and an indicator of the death of each parent. Age is measured in years. Gender is measured as a dichotomous indicator for being female. Death of each parent is asked separately in all three datasets and is included here as two separate indicator variables for the death of one's mother or father at any time. For the Add Health data, a parent is identified as the last person with whom the respondent co-resided that they identified as a parental figure. Death of a parent has been used as a standard predictor in stress events indices for adolescents and young adults, and in particular has been used successfully as a stress event predicting depressive symptoms with the Add Health Data [27,28].

Results

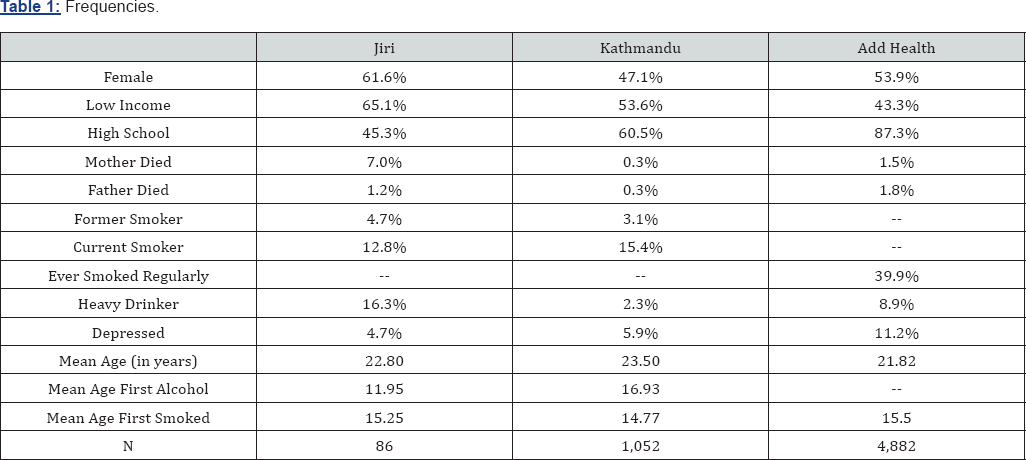

Table 1 shows the distribution of measures within each of the three datasets examined. Both the rural Nepal sample from the Jiri district and the nationally representative U.S. sample in Add Health are majority female, about 62% and 54% respectively. In the Kathmandu sample, however, men outnumber women by a small margin. Socioeconomic variables trend as one would expect with the poorest and least educated sample being from Jiri, the highest SES group being the Add Health sample, with Kathmandu falling in the middle. Indeed, in Jiri almost two-thirds of the sample can be considered low income with less than one-half obtaining 12 years of education. In the U.S. Add Health sample, on the other hand, less than half have low incomes and nearly nine in ten respondents have 12 or more years of education [29].

The prevalence of parental death across the three samples is similarly low with less than 2% experiencing the death of a father across all three samples. This low prevalence rate is mirrored for mothers' deaths in both Kathmandu and Add Health. However, the frequency of experiencing the death of a mother in the Jiri sample (7%) is more than three times higher than the rates in Kathmandu (0.3%) or Add Health (1.5%). This may reflect higher maternal birth-related mortality found more commonly in rural developing contexts. Because questions regarding smoking are asked somewhat differently in the Nepali and US datasets, descriptive frequencies are shown differently for the two countries. However, combining the percentages for 'current' and 'former' smokers in the Nepali data is relatively equivalent to the 'ever smoked regularly' question from Add Health. Doing so yields an ever smoked rate in Jiri of 17.5% and an ever smoked rate in Kathmandu of 18.5%. This is considerably lower than the Add Health ever smoked rate of almost 40%. Though one might expect age of onset differences to be important in explaining the lower Nepali percentages given the young adult nature of the data, the average age of first smoking is around 15 years across all three samples [30].

p<.10, *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

“Father's death excluded from Jiri models due to small sample size.

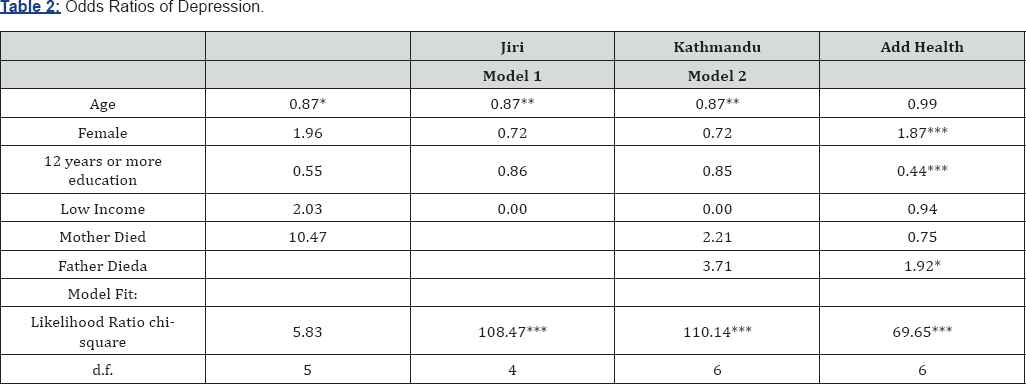

Alcohol consumption varies considerably across the three samples. Heavy drinking is most common in Jiri (16.3%) where the prevalence is almost twice that found in Add Health and is more than seven times the rate found in Kathmandu. A possible explanation for higher drinking rates in rural Nepal compared to Kathmandu may lie in the level of religiosity of these areas. Rural areas in Nepal tend to be more religiously active, and since for some Nepali religious groups ceremonies frequently include the use of alcoholic beverages, rates of regular alcohol consumption as measured here may reflect these common practices. Table 2 through 4 shows the results of binary logistic modeling for all three samples on each of the three measures of interest: being depressed, smoking, and heavy drinking. For all measures, models with and without the effects of parental death are examined in Kathmandu due to limited experience of these events within this population (0.3%). For the same reason, father’s death is excluded from all models using the Jiri data (of the 86 respondents, only one reported the death of a father) [31]. Table 2 shows odds ratios for predictors of being depressed in each of the three samples. In both the Nepali samples, the likelihood of being depressed declines with age. While the results do not reflect this finding in the Add Health sample, a declining age trend during adolescence rather than young adulthood has been observed using Add Health. For both Nepali samples, age is the only statistically significant predictor.

In Add Health, however, gender, education, and father's death are significant predictors of being depressed. Consistent with the large literature on depression in the U.S. context, young women are considerably more likely to report being depressed than young men. Also consistent with U.S. literature on depression, having more education appears to be a protective factor against becoming depressed, and experiencing a significantly stressful event such as a father's death is associated with greater likelihood of reporting depressive feelings. Though not statistically significant, the odds ratios for education and parental deaths in the Nepali samples are in the same direction as those in the Add Health sample and are, therefore, suggestive of similar causal patterns across urban/rural and developing/ developed contexts consistent with the fundamental cause thesis. However, the pattern for gender is not consistent. While the non-significant odds ratio for women in the Jiri sample is very similar in direction and magnitude to that found in Add Health, the same odds ratios for the Kathmandu data are in the opposite direction suggesting that men may be more likely to report being depressed than women. Given the strength and persistence of gender findings in previous research on depression, the Kathmandu results (even if considered only as indicating no gender difference) deviate significantly from expected findings and require further explanation. We speculate that this may be because urban Kathmandu actually affords women greater opportunities for attainment than are true in rural areas and traditional Nepali culture. It may also be the case that men are under greater stress in Kathmandu because, while they retain a dominant gender position, they are also obligated to be successful in non-traditional economic activities that characterize the urban economy [32].

Table 3 shows the results for models predicting having ever smoked across the three samples. Results across both Nepali samples are remarkably consistent. In both Jiri and Kathmandu, being older is associated with greater likelihood of smoking, and being female is strongly associated with significantly lower likelihood of smoking compared to men. Higher education is also significantly associated with lower odds of smoking in Kathmandu, and although not statistically significant, the odds ratio in the Jiri results is consistent with this finding. Low income status and parental death do not appear to be associated with smoking in either Nepali sample.

p<.10, *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

aFather's death excluded from Jiri models due to small sample size.

For the Add Health sample, reduced odds of smoking are similarly seen for women and persons with higher education level, which is consistent with the fundamental cause thesis. However, unlike in the Nepali data, age has no effect on the likelihood of smoking. Furthermore, having a low income appears to reduce the odds of smoking in the U.S. sample, a result opposite of that expected under a fundamental cause argument. However, this result may reflect the considerably higher costs of tobacco products in the U.S. context resulting from public health initiatives that create substantial taxes on tobacco products. In addition, the parental death stress events seem to be associated with elevated risk of smoking in the Add Health sample [33].

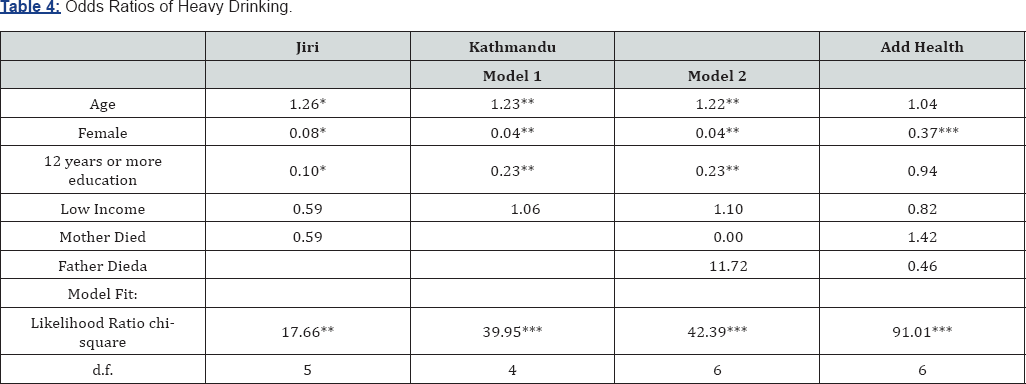

Table 4 shows models predicting heavy drinking across the Nepali and U.S. contexts. Results here are very similar to those in the models predicting ever smoking. Age is positively associated with heavy drinking in both Nepali locations, but has no effect in the Add Health sample. Across all three contexts, women are much less likely to be heavy drinkers than men. Greater education also appears as a protective factor against heavy drinking in both Nepali contexts, and although not statistically significant, the odds ratio for the U.S. results is in the same direction-a result consistent with the fundamental cause thesis. Although generally having low income does not appear to be associated with increased or reduced odds of heavy drinking, there is some suggestion that lower income results in slightly reduced odds of heavy drinking in the U.S.-again, perhaps reflecting elevated economic costs of alcohol in the U.S. versus Nepal due to taxation.

p<.10, *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

aFather's death excluded from Jiri models due to small sample size.

Discussion and Conclusion

Over twenty years ago, Link and Phelan put forth the idea that social factors could be the fundamental causes of illness resulting in consistent findings of health disparities across historical and social contexts. Since then, additional research has supported the fundamental cause thesis across multiple health outcomes and in a handful of cross-national studies. In the current study, we have sought to extend this literature by investigating the fundamental cause argument in the context of one of the least developed nations, Nepal. Moreover, we were able to examine the contrast between the effects of status on health in urban and rural Nepal, which represents the contrast between modernizing and traditional forms of social organization frequently found within developing contexts.

Our findings generally support the fundamental cause thesis in the U.S. as well as in both the rural and urban Nepalese data. In particular, despite the fact that the types of common illnesses and disease mechanisms across these three contexts as well as the nature of social statuses vary considerably, evidence suggests that lower educated people in all three contexts are at greater risk of depression and may be more likely to engage in the risky health-related behaviors of smoking and frequent alcohol consumption. In other words, even in one of the least developed regions of the world, rural Nepal, less education is associated with poorer health. The consistent importance of gender in our analyses is also consistent with some recent work in the fundamental cause area.

On the other hand, the association of low income with poorer health and health behavior is not consistent across these three contexts, which does not support the notion of fundamental causes. However, this lack of effect may due to the nature of this type of SES measure. Income, in general, is a more volatile measure of SES than others such as education or wealth given its short-term orientation (e.g., annual salaries in developed nations), and it may have less predictive value given the potential for compressed income variation in poorer, agrarian contexts like Jiri. Furthermore, the erratic behavior of the income measure may be more pronounced in agrarian versus industrialized settings. For example, in an industrialized society, wages tend to be relatively similar across adjacent years given the incremental process of raises and promotions, with periods of unemployment causing some fluctuations. In an agrarian economy, however, year-to-year fluctuations in income can be caused by relatively common environmental issues (e.g., drought, cold weather, heat waves, etc.) resulting in considerably more volatility in any income measure. As such, wealth, or other similarly long-term SES measures such as education, are likely more reliable in the context of least developed nations. Thus, our income results should be viewed with some skepticism.

There are several important limitations of the current study. First, it would be ideal to have identical measures across all three contexts, especially more detailed measures of health outcomes than the simplified ones used here (e.g., full depressive symptoms scales). Additionally, a more extensive set of comparable covariates would be desirable. Unfortunately, the availability of comparably measured data that allow for quantitative comparisons of a developed nation and the rural and urban sectors of a developing nation are quite limited. Future data collection is needed for a fuller assessment of the fundamental cause argument across such contexts. Second, the current study is also limited in that longitudinal data are simply not available for the Nepalese contexts. A more complete test of the fundamental cause thesis should utilize longitudinal data (as others have done in developed nations), and future data collection in Nepal should build on previous work in order to allow for longitudinal analyses. Third, the sample size in the rural Jiri area of Nepal is quite small as might be expected for a relatively sparsely populated area, resulting in a pronounced lack of statistical power. While it is easy to suggest collecting a larger sample to solve such an issue, the migratory realities of developing nations where rapid urbanizing is ongoing probably mean that adequate sample sizes from rural areas of these nations will become ever increasingly difficult to obtain.

Despite these limitations, the contribution of the current findings lies in the diversity of contexts included. It is difficult to imagine social and economic contexts more different than the United States and rural Nepal. The former is among the wealthiest industrialized settings with widely available advanced medical treatment, exceptional variability in individual economic resources, and a health profile dominated by chronic disorders. The latter is among the least developed settings with an agro-pastorial economy and widespread communicable disease, but with little medical treatment available. That SES appears to be related to health and health behavior similarly across these contexts evinces clear support for the fundamental cause argument.

References

- Baral N, Lamsal M, Koner BC, S Koirala (2002) Thyroid dysfunction in eastern Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 33: 638-641.

- Chang VW, Lauderdale DS (2009) Fundamental cause theory technological innovation, and health disparities: The case of cholesterol in the era of statins. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50(3): 245260.

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL (1994) Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology 30(4): 467-483.

- Gorstein J, Shreshtra RK, Pandey S, Adhikari RK, A Pradhan (2003) Current status of vitamin A deficiency and the national vitamin A control program in Nepal: Results of the 1998 national micronutrient status survey. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 12(1): 96-103.

- Kessler RC, Mc Gonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen, H-U and KS Kendler et al. (1994) Lifetime and 12-month Prevalence of DSM-III-R Psychiatric Disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51(1): 8-19.

- Khatlwada NR, Takizawa S, Tran TVN, M Inoue (2002) Groundwater contamination for sustainable water supply in Kathmandu valley, Nepal. Water Sci Technol 46(9): 147-154.

- Kim S, Dolecek TA, Davis FG (2010) Racial differences in stage of diagnosis and survival from epithelial ovarian cancer: A fundamental cause of disease approach. Social Science & Medicine 71(2): 274-281.

- Link BG, Northridge ME, Phelan JC, Ganz ML (1998) Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: On the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. The Milbank Quarterly 76(3): 375-402.

- Link BG, Phelan JC (2002) Mc Keown and the idea that social conditions are fundamental causes of disease. Am J Public Health 92(5): 730-732.

- Link BG, Phelan JC (1995) Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior pp. 80-94.

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Miech R, Westin EL (2008) The resources that matter: Fundamental social causes of health disparities and the challenge of intelligence. J Health and Soc Behav 49(1): 72-91.

- Mc Donough P, Worts D, Sacker A (2010) Socioeconomic inequalities in health dynamics: A comparison of Britain and the United States. Soc Sci Med 70(2): 251-260.

- Meadows SO, Brown JS, Elder GH (2006) Depressive symptoms, stress, and support: Gendered trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood. The Journal of Youth and Adolescence 35(1): 89-99.

- Murdoch DR, Harding EG, JT Dunn (1999) Persistence of iodine deficiency 25 years after initial correction efforts in the Khumbu region of Nepal. N Z Med J 112: 266-268.

- Olafsdottir S (2007) Fundamental causes of health disparities: Stratification, the welfare state, and health in the United States and Iceland. J Health Soc Behav 48(3): 239-253.

- Osrin D, Tumbahangphe KM, Shrestha D (2002) Cross sectional, community based study of care of newborn infants in Nepal. BMJ 325: 1063.

- Phelan JC, Link BG (2005) Controlling disease and creating dispartities: A fundamental cause perspective. J Gerontol B Psychol Soc Sci 2: 27-33.

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, B Lewin (2004) "Fundamental Causes" of Social Inequalities in Mortality: A Test of the Theory. J Health Soc Beh 45(3): 265-285.

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P (2010) Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 51(S): S28-S40.

- Rai SK, Hirai K, Ohno Y, T Matsumura (1997) Village health and sanitary profile from eastern hilly region, Nepal. The Kobe Journal of Medical Sciences 43: 121-133.

- Reeve CL, Basalik D (2010) Average state IQ, state wealth and racial composition as predictors of state health statistics: Partial support for 'g' as a fundamental cause of health disparities. Intelligence 38: 282289.

- Rous JJ, DR Hotchkiss (2003) Estimation of the determinants of household health care expenditures in Nepal with controls for endogenous illness and provider choice. Health Economics 12: 431-451.

- Roxburgh S (2009) Untangling inequalities: Gender, race, and socioeconomic differences in depression. Sociological Forum 24(2): 357-381.

- Rubin MS, Colen CG, Link BG (2009) Examination of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States from a fundamental cause perspective. American Journal of Public Health 100(6): 1053-1059.

- Shrestha RR, Shrestha MP, Upadhyat N (2003) Groundwater arsenic contamination, its health impact and mitigation program in Nepal. J Environ Sci Health Part A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng 38(1): 185200.

- Shrestha S (2002) Socio-cultural factors influencing adolescent pregnancy in rural Nepal. Inter J Adolescent Med Health 14(2): 101109.

- Smith C (1999) Blood Pressure of Sherpa Men in Modernizing Nepal. American Journal of Human Biology 11(4): 469-479.

- Swearingen EM, Cohen LH (1985) Measurement of adolescents' life events: The Junior High Life Experiences Survey. Am J Com Psychol 13(1): 69-85.

- Udry JR (2003) The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Waves I & II, 1994- 1996; Wave III, 2001- 2002. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA.

- Watkins D (1996) Within-Culture and Gender Differences in SelfConcept. J Cross-Cultural Psychology 27: 692-699.

- World Health Organization (2001) Selected health indicators.

- Williams-Blangero S, Subedi J, Upadhayay RP, Manral DB, Rai DR, et al. (1998) Genetic analysis of susceptibility to infection with Ascaris Lumbrioides. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 60(6): 921-926.

- Willson AE (2009) 'Fundamental causes' of health disparities: A comparative analysis of Canada and the United States. International Sociology 24(1): 93-113.