Non-Pharmacologic VTE Prophylaxis in Elderly

Suka Aryana*

Internal Medicine Department of Medical Faculty, Udayana University, Indonesia

Submission: February 08, 2018; Published: February 15, 2018

*Corresponding author: Suka Aryana, Geriatric Division, Internal Medicine Department of Medical Faculty, Udayana University, Sanglah Teaching Hospital, Bali, Indonesia, Email: aryanasuka@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Suka Aryana. Non-Pharmacologic VTE Prophylaxis in Elderly. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2018; 3(3): 555612. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2017.03.555612

Abstract

Dry Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) and is a significant potential health complication for hospitalised patients. Serious adverse outcomes may occur, including an increased risk of recurrent thrombosis, morbidity from post- thrombotic syndrome or death. The risk of developing VTE depends on the patient's background risk factors and upon the condition or procedure for which the patient is admitted. Effective prophylaxis will be achieved through assessment of risk factors and existing medical conditions with application of appropriate drug therapy and/or mechanical devices. This Standard guides the assessment of risks and strategies to reduce the risk of VTE with provision of VTE prophylaxis.

Assessing the benefit-risk ratio of anticoagulation is one of the most challenging issues in the individual elderly patient, patients at highest hemorrhagic risk often being those who would have the greatest benefit from anticoagulants. Some specific considerations are of utmost importance when using anticoagulants in the elderly to maximize safety of these treatments, including decreased renal function, co-morbidities and risk of falls, altered pharmacodynamics of anticoagulants especially VKAs, association with anti-platelet agents, patient education. To reduce the side effects of pharmacological agents and to increase the effectiveness of prophylaxis and treatment of DVT and PE, non-invasive method was introduced. The goal of this method is to achieve an augmentation of venous blood flow in lower limbs via external mechanical devices.

Introduction

The benefits of VTE prophylaxis often outweigh its risks, such as symptomatic DVT and PE, Fatal PE, costs of investigating symptomatic patients, risks and costs of treating unprevented VTE, increased future risk of recurrent VTE, and chronic post-thrombotic syndrome. There are various approaches in prophylaxis and management of DVT and PE that includes both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods. Subcutaneous heparin (unfractionated or fractionated) may be the most effective means of prophylaxis. However, neurological injuries and major bleeding often preclude its use due to the increased risk of hemorrhagic complications. Non- pharmacological methods may be favorable for DVT and PE prophylaxis in such cases.

To assist in reducing risk of VTE, commence prophylaxis as early as possible during the patient's admission or commence as scheduled after immediate care and risk assessment is carried out. Emergency Department clinicians should commence risk assessment and prophylaxis when the patient will not be seen by the in-patient team/consultant until the next day. Risk assessment must be undertaken for both medical and surgical patients who have significantly reduced mobility for three days or longer or are expected to have ongoing reduced mobility relative to their normal state and have one or more risk factors. Patients must remain adequately hydrated and must be encouraged to mobilize as soon as possible and to continue being mobile post discharge [1].

Goal of VTE prophylaxis

The main goals of VTE prophylaxis are to stop a clot from forming or growing and to reduce the chance of another clot developing. VTE prophylaxistreatment focuses on the appropriate selection of pharmacological and non-pharmacological/ mechanical approaches, based on the individual patient's risk factors and type of surgery. One element of VTE prophylaxis is early ambulation following surgery. However, physician orders such as "ambulation as tolerated" generally do not result in sufficient activity and associated prophylaxis. Therefore, in addition to ambulation, VTE prophylaxis options, in most cases, need to include pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological/ mechanical options.

There are two types of prophylaxis, pharmacological and mechanical. The use for thromboprophylaxis has to consider several things, such as the height of VTE prevalence, adverse consequences of VTE, efficacy and effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis [2]. Some agents are contraindicated or require a reduction of dose in elderly patients or those with renal impairment. Prescribers should refer to current product information to select a safe dose for individual patients, taking care to select the dose recommended for prophylaxis and not the dose recommended for therapeutic anticoagulation. Many drugs, including anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin), anti-platelet agents, selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antithrombotic agents may interact with prophylactic agents to increase the risk of bleeding. Decisions about appropriate concomitant use of these medications for VTE prophylaxis should be made on an individual patient basis in consultation with the Attending Medical Officer.

Where pharmacological prophylaxis is contraindicated, mechanical prophylaxis remains an option and should be considered, as indicated, until the patient is mobile. Patients having a risk ofbleeding must not be treated with pharmacological VTE prophylaxis [3]. Additional contraindications beyond bleeding risk may include:

a) Known hypersensitivity to agents used in pharmacological prophylaxis

b) History of, or current, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

c) Creatinine clearance <30mL/minute

The following are non-pharmacological or mechanical options for VTE prophylaxis:

a) Graduated Compression Stockings (GCS) for ambulant patients or Thrombo Embolic

b) Deterrent Stockings (TEDS) for immobile patients.

c) Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) or foot impulse devices (FID)

d) Intravascular filtration

Graduated Compression Stockings and Compression Devices

For surgical patients, thromboembolic deterrent stockings (TEDs) with appropriate pharmacological prophylaxis are usually provided until the patient is fully mobile. If pharmacological prophylaxis is contraindicated, the most appropriate mechanical device available (e.g. intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) or foot impulse devices (FID) should be used until the patient is mobile. All stockings must be fitted and worn correctly according to the manufacturer's recommendations. It should be noted that graduated compression stockings may increase the risk of falls in mobilizing patients. Patients should be instructed to wear appropriate non-slip footwear [4]. Stockings must be removed daily to assess skin condition and perfusion and to provide skin care. Active compression stocking gives higher pressure than passive compression stocking (16-22mmHg).

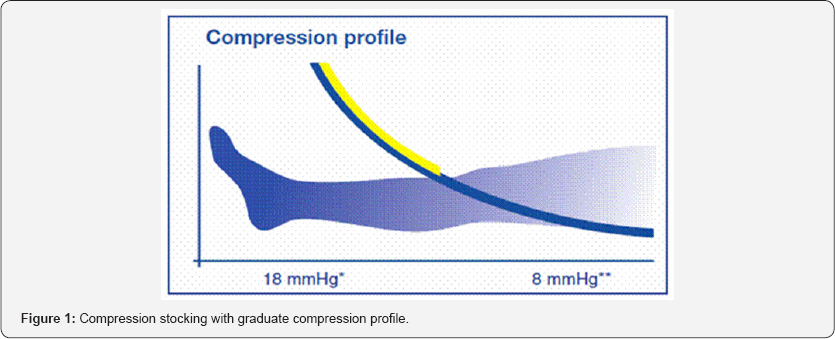

There are three different pressure level of compression stockings: moderate pressure (15-20 mmHg), strong compression (20-30 mmHg), and extra strong pressure (30-40 mmHg). Compression stocking can prevent thromboembolism in immobilized patients, repair lower limb vein blood flow, control the progressivity of vein and lymph disorders, and reduce the swelling. The compression level continuously decreasing from distal to proximal within the medically approved level of compression [5,6]. As conclusion, compression effectively prevents VTE due to the ability to increase the velocity of blood flow and reduced the static of vein (Figure 1).

Compression stockings may be contraindicated in patients with:

a) morbid obesity where correct fitting cannot be achieved

b) inflammatory conditions of the lower leg

c) severe peripheral arterial disease

d) Diabetic neuropathy (there is a risk of injury due to decreased sensation and discomfort if there is a problem with the fitting).

e) severe oedema of the legs

f) unusual leg deformity

g) allergy to stocking material

h) cardiac failure

IPC or FID can exacerbate lower limb ischemic disease and are contraindicated in patients with peripheral arterial disease or arterial ulcers.16 IPC is contraindicated in acute lower limb DVT [7].

Complications of Mechanical Prophylaxis

Incorrect fitting may result in bunching of the stockings resulting in leg ulceration, pressure ulcers, slipping and falling on mobilization.

References

- Robert-Ebadi H, Le Gal G, Righini M (2009) Use of anticoagulants in elderly patients: practical recommendations. Clinical Interventions in Aging 4: 165-177.

- Eikelboom JW, Weitz JI (2010) Update on Antithrombotic Therapy New Anticoagulants. Circulation 121: 1523-1532.

- Albert B Lowenfels (2010) Venous Thromboembolism & Prophylaxis in surgical patients.

- Kouka N, Len Nass, Feist W Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Management Methods of DVT and Pulmonary Embolism.

- NSW (2010) Prevention of VTE Policy. Sydney, USA.

- Menaka Pai, James D Douketis, Fa CP, FCCP (2010) Preventing venous thromboembolism in long-term care residents: Cautious advice based on limited data. Cleveland Clinic Journal Of Medicine 77(2): 123-130.

- Enrico Tincani, Mark A Crowther, Fabrizio Turrini, Domenico Prisco (2007) Prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in the elderly patient. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2(2): 237-246.