Care at the End of Life - Conscientious Practice

Riquelme-Heras Hector* and Gomez-Celina

Family Medicine Department, Academic Board of Medical School, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, USA

Submission: February 06, 2018; Published: February 12, 2018

*Corresponding author: Riquelme-HerasHector, Family Medicine Department, Academic Board of Medical School, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Mexico, USA, Email: riquelme@doctor.com

How to cite this article: Gomez-Celina, Riquelme-Heras Hector. Care at the End of Life - Conscientious Practice. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2018; 3(3): 555611. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2017.03.555611

Short Communication

Terminal diseases require specialized treatments that in some cases can be challenging, the clarity of the ethical and legal aspects include the ability of patients or their surrogates to refuse treatments that prolong life, including hydration and artificial nutrition; the ethical acceptability of suspending or not initiating treatments that maintain life; and the right of patients to receive high doses of pain medication, even when those doses represent the risk of shortening their lives [1].

Ethical concerns often emerge in end-of-life care. Through much discussion, debate and cases brought to the court, a consensus has been reached regarding professional standards of ethical practice in many aspects of end-of-life care. On the other hand, the debate on the ethics of physician-assisted suicide continues, which is illegal in most countries. In each of these aspects of medical practice, such as the rejection of treatments that sustain life, the failure to administer or suspend life support, the use of high doses of pain medication at the end of life, continues to be loaded with emotions and challenges for doctors, patients, and families [2].

Sometimes, despite the legal clarity of ethical standards and patients' rights, and their values and choices, they may come into conflict with the doctors who treat them [3]. Some of the conflicts that may emerge in the context of decision-making in end-of-life care are due to confusion in the language. The terms used in decision-making discussions at the end- of- life carry strong emotional situations. Similar situations occur with different terms; each has a certain connotation. For example, "doctor-assisting suicides" and "doctor helping to die", each describes a similar act, but suggest particular points of view in relation to the act. Conscious practice is defined as "taking of professional actions that are consistent with one's ethical and moral beliefs, and avoiding actions that are contrary to one's beliefs" [4].

The patient's rights to refuse treatment or seek a given treatment do not require a clinician to participate in the provision of treatment when the patient's choices conflict with the physician's values. The right of the doctor to a conscious practice allows him to withdraw from the treatment of a patient once he has ensured that he will receive care by a colleague. The right of patients or their surrogates to reject treatments that sustain life has been well established by law in the courts. The Quinlan decision in 1975 established the right to discontinue mechanical ventilation and, by inference, other maintenance life treatments [5]. When patients have lost the ability to make decisions, some states have set high standards for suspending hydration and artificial nutrition.

The ethical standards for physicians specify that there are no differences between not administering and withdrawing the same treatment once it has been initiated. The act of discontinuing hydration and nutrition in a young and stable patient causes a greater emotional response than choosing not to perform CPR in an elderly patient with multi organ failure. However, the emotional reaction generated by this case does not alter the fundamental ethical principle that patients and their surrogates can choose the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments, including hydration and artificial nutrition, once they have already been initiated. The right to withdraw or suspend treatment protects patients and their surrogates from the pressure of urgent decision-making.

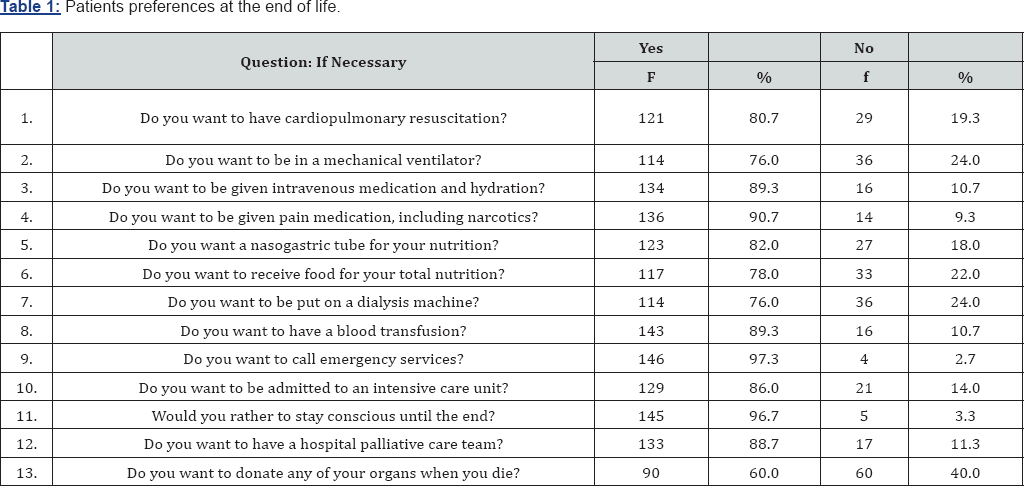

Regarding the quality of life if you ask: Do you want to live many years or less, but with quality? Seventeen percent want to live for many years and 83% prefer to live less, but with quality. Elderly patients have preferences if hospitalized [6,7] (Table 1). Such pressures can accelerate choices that limit treatment in some who would choose a treatment trial and which might benefit them. When starting a treatment, two things can be obtained. First, doctors, patients, and surrogates can obtain greater certainty in the diagnosis. Second, time may allow more clarity and consensus to know the wishes and preferences of the patient [8].

n=150

The right to a conscious practice allows the physician to withdraw from a patient's treatment without penalty, while respecting the patient's right to refuse treatment. For physicians with strong moral opposition to patient decisions and surrogates in relation to treatment, providing assistance in this also can means in some cases a violation of their personal morality [8]. Ethical standards of professional practice do not require that the doctor identifies another doctor to take over patient care. However, the doctor is obligated to provide all appropriate comfort measures until the moment of transfer of the patient and have the file available to the doctor who will continue with the patient’s care.

Patients should be offered the opportunity to benefit from a range of treatments that can help them in pain management, although they may also choose not to use these treatments. Patients and families who choose aggressive control for symptoms should be informed of the risks of sedation and accelerated death that may result from their decision [3]. Physicians should be careful and remind patients and families that, in relation to the results of treatment, the cause of death is the underlying disease, not the treatment for the pain itself. Also assure them that they know that relief of symptoms with high doses rarely causes death but that it can be an inevitable result. If this happens, it is both ethical and legal.

There are doctors who are not comfortable with aggressive control of symptoms. In these cases, doctors may believe that hospitalization and treatment may serve the best interests of the patient and may not accept treating symptoms at home in an aggressive manner [9]. Regarding to challenges that involve cases related to treatment at the end- of- life, it requires great sensitivity to all involved and respect for the values and beliefs of all of them. Clarity in the ethical and legal aspects about which patients would choose for themselves does not require that all those involved in patient care agree with their choice. In a pluralist society, there must be respect not only for individual autonomy but also for the ability of others to differ in their values and even respect their refusal to participate in the care of these patients.

Evidence indicates that terminally ill patients continue to experience uncontrollable pain, and that improving pain management is an important priority [1]. However, improvement in pain management practices will not eliminate all requests for assisted suicide. For many patients, hopelessness and loss of independence are the most important factors in their request. Depression can be an important factor in patients with terminal illnesses. Diagnosing depression in those with terminal illnesses can be a challenge. The physical signs of depression such as fatigue, changes in sleep, energy, libido, and weight loss-are often present as a result of advances in the disease. Most terminal patients will have periods of depressive changes or sadness. However, it is usually an inappropriate emotional response to illness, imminent death and is best described as mourning rather than depression [2].

The diagnosis of depression in terminal patients is more reliable when it is made based on the cognitive signs of depression. Depressed patients often present with anhedonia, guilt and remorse about the past, or loss of self-esteem. Social factors may also play a role in the desire of some patients to request assisted suicide. Many patients do not want to be a burden to their families or loved ones. Others have very limited social support. Patients should be assured that their families will face the nuisance of their care with affection and love. The resource of hospital care must also be available [10]. A study shows that most patients in case of presenting a terminal illness prefer to die at home [6]. Doctors must decide to what extent they are willing to help the patient to assist him/her in the terminal stage. This intense personal decision will be a challenge for each doctor to carefully examine his/her own ethical beliefs.

Those who wish to help patients at first may later change their views according to the patients and their circumstances. The right to a conscious practice supports the right of the physician to withdraw from the care of a patient who chooses a treatment opposed to his/her values, judgment and professional knowledge. The Institutions also have the right to a conscious practice and therefore to the right to reject their employees participating in practices contrary to the fundamental values of the institution. The ethical standards of end-of-life care originated in large part from the fundamentals of respect for patient autonomy-principally the right to reject unwanted treatments [3]. At the end of life, patients have the ethical and legal right to refuse treatments that prolong life. Do we as a society support the right to comfort in the final months of life?

References

- Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J (1997) what is wrong with end-of-life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc 45(11): 1339-1344.

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, Neilly M, McIntyre L, et al. (2000) Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. Jama 284(19): 2476-2482.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, et al. (2008) Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. Jama 300(14): 1665-1673.

- Haley K, Lee M (1998) The Oregon Death with Dignity Act: A guidebook for health care providers. Center for Ethics in Health Care, Oregon Health Sciences University.

- Beresford HR (1977) The Quinlan decision: problems and legislative alternatives. Ann Neurol 2(1): 74-81.

- Riquelme Heras H, Barron Garza F, Gutierrez Herrera R, Farfan Trevino N (2016) Actitudes del adulto mayor ante las ultimas voluntades en la consulta de Medicina familiar. Rev Mex Med Fam 3(1): 4-6.

- Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, et al. (2008) Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 148(2): 147-159.

- Hinkka H, Kosunen E, Lammi UK, Metsanoja R, Puustelli A, et al.(2002) Decision-making in terminal care: a survey of Finnish doctors' treatment decisions in end-of-life scenarios involving a terminal cancer and a terminal dementia patient. Palliat Med 16(3): 195-204.

- Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AG, et al.(2003) Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers?. J Pain Symptom Manage 25(2): 150-168.

- Gott M, Seymour J, Bellamy G, Clark D, Ahmedzai S (2004) Older people's views about home as a place of care at the end of life. Palliat Med 18(5): 460-467.