Social Network and Support, Self-Rated Health, and Loneliness as Predictors of Risk for Depression Among pre-Frail and Frail Older People in Sweden

Faronbi J O.1,2,3*, Gustafsson S1,2, Berglund 2,4 Ottenvall-Hammar I1,2, Dahlin-Ivanoff, S1,2

1The Frail Elderly Research Support Group (FRESH), Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, the Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University,

2 The Gothenburg University Centre for Ageing and Health (Age Cap), Sweden

3Department of Nursing Science, College of Health Science, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

4Institute of Health and Care Sciences, the Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University, Sweden

Submission: September 19, 2017; Published: September 22, 2017

*Corresponding author: Joel O Faronbi, The Frail Elderly Research Support Group (FRESH), Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, The Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University, Sweden; Tel: +46734040420; Email: joel.faronbi@gu.se & jfaronbi@cartafrica.org

How to cite this article: Joel O F, Susanne G, Helene B, Isabelle O H, Dahlin-I, et al . Social Network and Support, Self-Rated Health, and Loneliness as Predictors of Risk for Depression Among pre-Frail and Frail Older People in Sweden. OAJ Gerontol& Geriatric Med. 2017; 2(5): 555597 DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2017.02.555597

Abstract

Introduction: Family and social network are indispensable to the well-being of the older people. However, little has been documented about benefits of the social network and support in reducing the risk for depression among older persons in Sweden. This study aims to examine the relationship between social network and social support, loneliness, and self-rated health among older Swedish people and to determine the ability of these variables (and personal characteristics) to predict the risk for depression among pre-frail and frail older people.

Methodology: This study analysed aggregated data from three randomised controlled studies, which included pre-frail and frail older Swedish adults age 65 years and above. Analyses were done using chi-square, ANOVA, and multiple regressions (in Stata v14).

Results: Findings from the analysis revealed that out of 737 respondents included in this study, 27.5% were at risk for depression (CI: 24.31, 30.78), 54.8% were living alone and 12.5% had no children. Furthermore, factors that statistically predicted the risk for depression include having a confidant (β=1.32, p;=0.006) loneliness (β=11.47,p=0.000, self-rated health (β=-2.60, p=0.000), changes in loneliness (β=-10.16, p=0.000), number of children (β=0.78, p=0.000), number of confidant (β=-0.19, p=0.068) and living alone (β=-0.61, p=0.005).

Conclusion: This study concluded that a large number of the older adults in this population is at risk for depression and factors that predict risk for depression include having a confident, living-alone, number of children, loneliness and poorer self-rated health. Therefore, health- promoting activities that encourage interaction and communication among the older adults should be implemented to promote their well-being.

Keywords: Confidant, community-dwelling, living alone, older adults, well-being

Abbreviations: EPRZ: Elderly People in the Risk Zone; PAMC: Promoting Aging Migrants' Capabilities; GDS: Global Depression Scale; ADL: Activity of Daily Living; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination

Introduction

Social network and support are indispensable to the wellbeing of the older people. O’Caoimh, Cornally [1] opined that caregiver networks are a central component in the management of frail and functionally impaired community-dwelling older adults. Social networks can be defined as the web of identified social relationships that surround an individual and the characteristics of those linkages [2,3]. It is the set of people with whom one maintains social contact or some form of social bond that may offer help or support in a variety of situations [2,3]. Social support refers to the perceived available resources from people who individuals trust and on whom they can rely [4]. It is related to individual's perceptions of the degree to which social relations offer different forms of resources (functions) such as material aid or emotional support [2] Benefits of social support and networks have been linked empirically to a number of positive social and psychological outcomes [5]. Results are consistent with the hypothesis that lower reported social support is an important reason for increases in depressive symptoms found among older adult populations [6]. Social support and social networks are also among the psychosocial influences of physical and mental well-being [7].

On the other hand, the consequences of absence of social support has been associated with poorer mental health and reduced cognitive performance, and objective social isolation [8], poorer mental health performance [9], declining health, loneliness [10], and mortality [11]. It also includes the risk of institutionalization and mortality of older persons [12]. However, Chappell and Badger [13] observed that living alone or having no children, and many measures of social isolation are not related to well-being.

As a person increases in age, the ability of systems in the body to perform their basic functions deteriorate and frailty set in [14]. Frailty refers to a multi-system deterioration of the reserve capacity at older ages, resulting in increased vulnerability to stressors [15]. Similarly, pre-frailty is defined as having less than three of five physical frailty criteria (low grip strength, low energy, slowed walking speed, low physical activity, and/or unintentional weight loss) [16]. This often necessitates the need for support from a significant person who might be their children, relatives, friends or governmental and non-governmental agency.

The availability of a significant member of the family may not be a guarantee that there will be an improvement in the wellbeing of the elderly. There are possibilities for an older adult to be suffering in the midst of plenty. It has been argued that people must have connections with other people (network) in order to receive social support, but social connections do not guarantee access to social support. Similarly, the ability of social support and network to mitigate the impact of living alone, poor health and loneliness on the risk for depression has not been explored among the pre-frail and frail older persons in Sweden. Efforts geared towards investing social network and support will have a multiplying effect on the health promotion of the older people.

Among the Swedish population, the number of older persons without children is on the increase; similarly, many of these older adults are living alone. This may be associated with childlessness or those whose children have already left home. This phenomenon makes them at risk for social isolation and loneliness and its consequences such as poor psychosocial well-being including risk for depression. However, it has not been well-established if living alone automatically translates to loneliness and the risk for depression among this population. The effect of modifiers such as social networks and social support may be at play. Seeking to support the advancement of knowledge on this subject, this study examined the influence of social network and support, self-rated health, and loneliness on the risk for depression among pre-frail and frail older persons aged 65 and over in Sweden. We thereby hypothesised that social network and support, self-rated health, and loneliness will not predict the risk for depression among the older adults.

Methodology

In this secondary analysis, we used baseline data aggregated from three randomized controlled trials namely: the Elderly People in the Risk Zone EPRZ [17], Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People [18], and the Promoting Aging Migrants' CapabilitiesPAMC [19]. The three studies received ethical clearance from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg. The protocol numbers are as follows: EPRZ (# 65007) Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People (#413-08), and PAMC (# 821-11). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Participants and Setting

The settings for the three studies were selected urban districts in a large city in western Sweden. The urban districts represented regions with high, middle and low socioeconomic parameters (e.g. general income level, sickness rate), and contained a mix of self-owned houses and apartment blocks. The population for the study comprises a representative sample of pre-frail and frail community-dwelling older adults 65 years to 99 who lived in ordinary housing and are either independent or dependent in Activity of Daily Living (ADL). The selection for EPRZ and PAMC took a similar pattern [20,21]. Participants in EPRZ and PAMC were randomly selected from the official registers in the urban district and were invited to participate in the study either through a letter and a telephone call. During the call, selected individuals were informed verbally about the study and given the opportunity to ask questions if anything was unclear. They were also asked personally if they would like to participate in data collection. Likewise, participants of the Continuum of Care study were recruited from the emergency department at Molndal Hospital and were followed-up to their home for data collection [22] in order for the sample to represent different levels of frailty. In addition, the PAMC included persons who migrated from any of the selected European countries (Finland and the Western Balkan region) and were residents in Sweden before the period of data collection [17-19]. All participants were cognitively intact with a score over 80% of Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [23].

The original study population comprises EPRZ: 459 persons, Continuum of Care: 161 persons, and PAMC: 131 persons, which gave a total of 751 participants. However, only 737 participants who had complete data on selected variables were used in the analysis of this study.

Data Collection

The studies were conducted as follows: EPRZ (2007 to 2011), Continuum of Care (2008 to 2011), and the PAMC (2012 to 2016). Baseline data from all three studies were used for the present study. All data were collected by trained research assistants (Occupational therapist, Physiotherapist, Registered nurse or Social worker) using a face-to-face approach in the participant's home or in another place if the participant wished. The items and the response alternatives were read to the participants and, if needed, shown on a paper. The research assistants were proficient in the languages spoken by the participants and were trained in interviewing, assessing and observing, according to the guidelines for the different outcome measurements. To ensure standardization of the assessments, study protocol meetings were held regularly throughout the periods of data collection.

Instruments for Data Collection

In all the studies, data were collected using a comprehensive interviewer administered questionnaire, which contained all the variables such as risk for depression, a number of children, confidants, and self-rated health. The instruments were written in participants' mother tongue.

Demographic Variables

Five demographic characteristics were used in this study. These include age, gender, level of education, profession before retirement, and living arrangement (living alone or not) (Figure 1).

Independent Variables

Social network: This is defined as a set of individual family members, relatives or friends who are present around an older person and there is an exchange of physical, financial or emotional resources between them. In this study, the social network was measured by the following variables: having children, number of children, distance to children, confidant (someone to trust), the number of confidants. Item on children was rated as yes or no, participants were asked on the number of children they have. Similarly, participants were asked to state the distance to their closest child. In addition, they were asked whether they have anyone to trust or confide in (confidant) and to state the number of those people (Figure 1).

Social support: Social support refers to the individual who an older person turns to for physical, financial or emotional help or assistance. This was assessed by asking participants a question on the source of help and it was assessed using an item questions asking who do they turn to when ill, when they need practical help, when they need advice or when they need to talk about personal troubles. Options range from (a) Husband / wife / partner (b) Non-cohabitant partner (c) child (d) Other relatives (e) Neighbours (f) Friends (g) Home care /nursing care, (h) Voluntary organization and others (i) and have no one to turn to. These were grouped into three categories representing how close they are to the old person. These categories are: Category One represents the closest source of help and it comprises (a) Husband/wife/partner (b) Non-cohabitant partner and (c)Children. Similarly, Category Two, representing a closer source of help. This includes other relatives (e) Neighbours (f) Friends. The third category represents the professional or paid assistance or non-governmental organization which includes (g). Home care / nursing / or Voluntary organization.

Self-rated health was measured by a single item asking respondents to rate their health on a 5-point scale. The options are Excellent, Very good, Good, Fairly and Bad [24]. Any individual with excellent, very good and good was categorised as good self-rated health while anyone who choose fairly and bad was categorised as poor self-rated health.

Loneliness is a subjective assessment and relates to individuals' perceived levels of isolation and satisfaction with existing relationships [25]. It was assessed using an item which asked the respondent to state whether they were lonely or not based on the following options: No, never, Yes, rarely, Yes sometimes, and Yes, often. The "no" option represents the absence of loneliness and the "yes" options were grouped together to signify the presence of loneliness. This was also followed by a question that asked if they were lonely more than ten years ago. Responses were Yes, more, No difference and No, less.

Dependent Variable

The risk for depression was measured with the aid of the Global Depression Scale (GDS)-20 [26]. The GDS is a 20-item selfreport scale measuring supposed manifestations of depression with yes or no option representing 1 and 0 respectively with a total score ranging from 0 to 20. The score for depression as measured by the GD20 ranges from 0 to 20 and a cut-off point for risk for depression was 5 [27]. Persons with a score above the cutoff point are regarded as having the risk for depression.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using frequency and percentage to understand the characteristics of the study sample. In addition, chi-square and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni adjustments for multiple comparisons was conducted to determine the association between each of the independent variables [social network (children, number of children, number of confidant, confidant), and social support (source of support), loneliness, changes in loneliness, and selfrated health] and all covariates (older people characteristics including age, gender, profession, education and living alone) to find significant indicators (used a level at 0.05) on the dependent variable (risk for depression). Furthermore, forward stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the predictive effect of the independent variables on the risk for depression. All the independent variables, as well as covariates, were included in the model. All analyses were performed using STATA14 statistical software (Stata Corp, USA)

Results

The age of the respondents ranges from 65 to 97 with a mean of 81.34 years (±6.4). The median age was 82 years and 72.5% of participants were within the age 80-89 categories. There was a preponderance of female participants (59.7%) to male. It also revealed that 27.5% had elementary school level or lower and that 50.3% were white collar workers before retirement (Table 1).

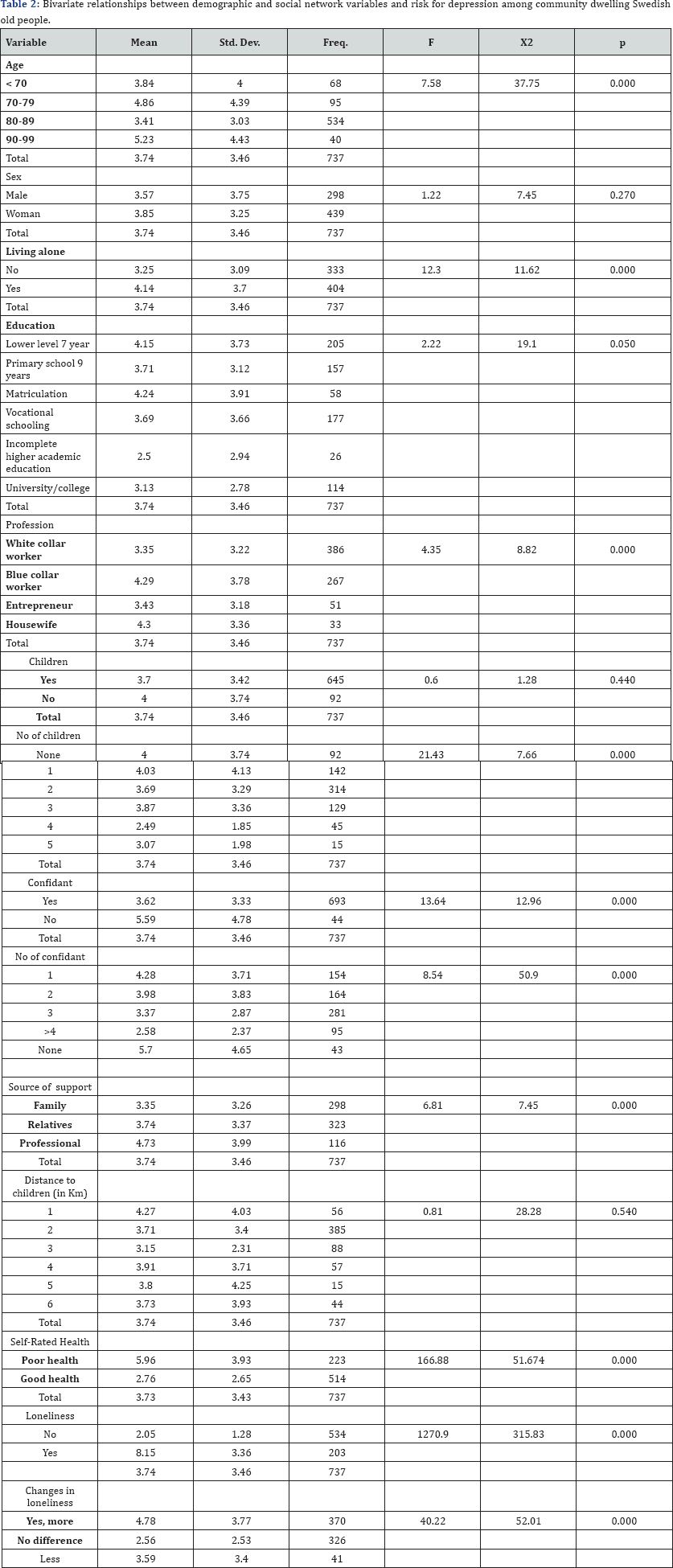

Findings from the analysis revealed that out of 737 respondents included in this study, the mean score for depression in this study was 3.79 and 27.54% (95% CI: 24.31, 30.78) were at risk for depression. A bivariate analysis was conducted and the following factors were significantly associated with risk for depression among the older people: Age (p = 0.000), living alone (p = 0.000), profession (p = 0.000), confidant (p = 0.000), the number of children (p = 0.000), source of support (p = 0.000), self-rated health and loneliness (p = 0.000). However, education, gender, and having children and were not significantly associated with risk for depression (Table 2).

A multiple regression was conducted to test the predictive effect of demographic and social network variables the following independent variables: Age, sex, living alone, number of children, distance to children, having a confidant or someone to trust, number of confidant, loneliness, and changes in loneliness over the years, and sources of support when ill. In the analysis, distance to children was omitted because on colinearity with children. Using a stepwise regression method, it was found that the independent variables explain a significant amount of the variance in the value of risk for depression, F (13, 723) = 40.18 p <.000, R2 = 0.42, R2Adjusted = 0.41)]. These variables: Confidant (β=1.32, p=0.006), loneliness (β=11.47, p=0.000), self-rated health (β=-2.60, p=0.000), changes in loneliness (β=- 10.16, p=0.000), number of children (β=0.78, p=0.000), number of confidant (β=-0.19, p=0.068), living alone (β=-0.61, p=0.005) significantly predicted the risk for depression (Table 3).

Discussion

Findings from this secondary analysis revealed that 27.5 % of the pre-frail and frail older adults above 65 years in Sweden are at risk for depression. In addition, variables that predict risk for depression include having a confidant, loneliness, self-rated health, changes in loneliness, number of children, number of confidants, and living alone.

Findings from this study underscore the inestimable contributions of the social network and support to the wellbeing of the older adults. Social network and support have a direct correlation with risk for depression. Similar findings have been observed by Santiago and Mattos [28] and Litwin [29] who documented that social support provision was positively associated with subjective health among Arab-Israelis. The presence or absence of a significant person around an individual will subsequently positively influence the risk for depression among the older adults.

Findings from this study also revealed that having children is a protective factor against the risk for depression among the older people. This is in consonant with Herman-Stahl, Ashley [30] who concluded that those who remain childless are indeed faced with lower levels of psychological well-being, as compared to parents who live with children and people whose children have already left the parental home. This is also supported by Chou and Chi [31] submission that childlessness is a stronger and more consistent risk factor for psychological well-being such as loneliness and depression in Chinese older adults. Furthermore, Carayanni, Stylianopoulou [32] observed that being childless was associated with the prevalence of depressive symptoms among women. This is however contrary to the finding from a previous study Zhang and Hayward [33] who posited that childlessness per se did not significantly increase the prevalence of loneliness and depression at advanced ages, net of other factors. Having someone to talk to or confide in seems to be a protective factor against risk for depression among the older people in this study than having children. Findings from this study revealed that having a confidant or someone to talk to was significant in predicting the risk for depression. The implication of this is that ability to find someone to talk to or confide in is more important to the well-being of the older people who may not necessarily be their offspring. This may be related to the kind of family structure that exists in this study population whereby, older people are living alone without any of their children or relatives around them. This finding further stresses the need to promote communication and interaction through health-promoting intervention for the older adults.

The number of numbers of connections and networks (children and friends) is also important to the well-being of the older adults. This suggests that there may be strength in the quantity of the network. This is supported by Rosenquist, Fowler [30] who reported that people who have a significantly worse score on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale also have fewer friends. Similarly, a study by Ross and Mirowsky [31] also showed that social connection decreased depression among the participants in their study. Further scrutiny of the source of support revealed that friends and other relatives contribute significantly to the well-being of the older people. This finding emphasises the importance of social connection and support for the older people which may not necessarily come from the children or immediate family, but from those whom they are interacting with. This may also explain the difference in the family structure and support system for the older people in Europe and in some developing nations such as Africa and Asia.

Among the African and Asian communities, the care and support for older people are hinged upon the family members. Children play a significant role in the care of the older adults. This situation is different in this study population. Having children was not significantly related to the outcome variable (risk for depression). Compared to the African or Asian where older adults live within the extended traditional family system, in this study population, older adults live on their own. The risk of living alone would even be more among those who have lost their partners.

Furthermore, the number of children is important in the model. Having up to four children was associated with the outcome variable. It was protective for the risk of depression. It is important to point out that the sample population comprised a mixed group. The immigrant's Swedish residents are generally different from the indigenous one in regard to family size. Unlike the native who typically have one or two and quite a good number did not have any child. The immigrants tend to have more, although, most of these migrants have lived in Sweden for more than 20 years, they have a higher tendency to have more children compare to the native. The proportions of migrants with more than four children almost double the original native (6.8%: 11.2%) [19].

Therefore, efforts to improve health and well-being among the older adults not only must address the consequences of illness and disease but must also attend to older adults' social connections. This may be inevitable owing to the unprecedented reduction in the fertility rate facing most European nations. In addition, interventions to increase participation in social activity among the older people, such as health-promoting initiatives, should be given a priority.

This study indicated that a substantial number of the prefrail and frail older adults in Sweden are at risk for depression. Although, the prevalence of depression in this population is lower than what was obtained from other studies conducted among institutionalised older adults [28,32,33], it is however, higher than the estimates expected from community studies which is put at between 11.5% and 13.5% [34,35]. This high prevalence may be related to the presence of risk factors such as loneliness, poor self-rated health, living alone and others that have been shown to be statically correlated with depression. Considering the high rate of risk for depression in this population together with its associated risk factors, it must, therefore, be considered a major problem that warrants urgent attention. Furthermore, Goosby, Bellatorre [36] declared that depressive symptoms were a conduit through which loneliness influenced certain health outcomes. These authors further stressed that there is a strong connection between depressive symptoms, poor self-rated health, and loneliness.

Self-rated health is also a strong predictor of overall wellbeing and mortality, and it is highly correlated with depression [36]. One possible reason for this is that the advanced age may be associated with decreased functional capacity, a decrease in social activities and illness symptoms and hence, the older adults may perceive and rate their health as being poor, and this might place them at a risk for depression. Besides, all the participants in the continuum of care project were individuals with at least one chronic illness, which suggests poor health. Results from this research suggest that much work is needed to reduce illness and promote the health of older people.

Findings from this study have also shown the predictive effect of living alone on the risk for depression among the older persons. This supports Lim and Kua [37] who reported that the depression score was associated with living alone among the older persons in Singapore. Similarly, studies by Cheng, Fung [38], Chou and Chi [39] also reported that older persons living alone were more likely to be depressed. Living alone may engender social isolation especially among those with limited social contacts thereby predisposing to more depression [40]. However, this is contrary to some authors who reported that living alone was not associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms [41,42]. This contrary opinion may be related to the fact that although a person may be living alone, but may not benecessarily isolated. The person may be remotely engaged in social interaction and other activities that mitigate the effect of social isolation.

In view of the ability of social connection and support to mitigate the negative consequences of the major health problems in this study, the effort geared towards promoting interaction, as well as provision and receipt of support from friends and relatives of the older adults will go a long way in improving the well-being of our older people.

The main limitation of the study is related to the self-report nature of the information provided during data collection and these were not objectively and clinically validated, and there might have possibly led to some bias. However, findings from this study provide significant insights into the interplay of invaluable contribution of the social support and network to the well-being of the older adults in Sweden and other countries with similar settings.

Conclusion

This study concluded that risk for depression is highly prevalent among pre-frail and frail older adults above 65 years in Sweden. It also concluded that having a confidant rather than having children is important to mitigating the consequences of risk for depression among the older adults. In addition, loneliness, poorer self-rated health, and living alone are some of the factors that predict risk for depression. Therefore, activities that promote interaction and communication among the older adults should be encouraged. This could also be useful for early identification and treatment of older people with the risk for depression, which is highly prevalent in this population.

Key Points

a) The risk for depression is highly prevalent in pre-frail and frail older adults above 65 years in Sweden.

b) Having a confidant (social connection) rather than having children is important to the well-being of the older adults.

c) Loneliness, living alone, a small number of children, and poor self-rated health are predictors for risk for depression.

d) Having a large number of networks and connections are important to the well-being of the older adults.

Acknowledgement

"This research was supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Center and the University of the Witwatersrand and funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK) (Grant No: 087547/Z/08/Z), the Department for International Development (DfID) under the Development Partnerships in Higher Education (DelPHE), the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No: B 8606), the Ford Foundation (Grant No: 1100-0399), Google.Org (Grant No: 191994), Sida (Grant No: 54100029) and MacArthur Foundation Grant No: 10-95915-000-INP".

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- O'Caoimh R, Cornally N, Svendrovski A, Weathers E, Fitz Gerald C, et al. (2015) Measuring the Effect of Carers on Patients' Risk of Adverse Healthcare Outcomes Using the Caregiver Network Score. J Frailty Aging 5(2): 104-110.

- Fontanini H, Z Marshman, M Vettore (2015) Social support and social network as intermediary social determinants of dental caries in adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 43(2): 172-182.

- Caetano SC, CM Silva, MV Vettore (2013) Gender differences in the association of perceived social support and social network with selfrated health status among older adults: a population-based study in Brazil. BMC geriatrics 13(1): 122.

- Kawachi I, L Berkman (2000) Social cohesion, social capital, and health. Social epidemiology. Pp. 174-190.

- Ashida S, CA Heaney (2008) Differential associations of social support and social connectedness with structural features of social networks and the health status of older adults. J Aging Health 20(7): 872-893.

- NewsomJT, R Schulz (1996) Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychol Aging 11(1): 34-44.

- Israel BA (1982) Social networks and health status: Linking theory, research, and practice. Patient counselling and health education 4(2): 65-79.

- Casey ANS, Lee-Fay Low, Yun-Hee Jeon, Henry Brodaty (2016) Residents Perceptions of Friendship and Positive Social Networks Within a Nursing Home. The Gerontologist 5(1): 855-867.

- Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cacioppo JT (2014) Toward a neurology of loneliness. Psychological bulletin 140(6): 1464-1504.

- Luanaigh CO, BA Lawlor (2008) Loneliness and the health of older people. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 23(12): 12131221.

- Cohen S (2004) Social relationships and health. American psychologist 59(8): 676-684.

- Baron Epel O, N Garty, MS Green (2007) Inequalities in use of health services among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Health Serv Res 42(3 pt 1): 1008-1019.

- Chappell NL, M Badger (1989) Social isolation and well-being. Journal of Gerontology 44(5): S169-S176.

- Avlund K (2004) Disability in old age. Longitudinal population-based studies of the disablement process. Dan Med Bull 51(4): 315-349.

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G, et al. (2004) Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(3): M255-M263.

- Fried LP1, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, et al., (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56(3): p. M146-M157.

- Dahlin-Ivanoff S (2010) Elderly persons in the risk zone. Design of a multidimensional, health-promoting, randomised three-armed controlled trial for "prefrail" people of 80+ years living at home. BMC Geriatrics 110: 27.

- Wilhelmson k (2011) Design of a randomized controlled study of a multi-professional and multidimensional intervention targeting frail elderly people. BMC geriatrics 11(1): 24.

- Gustafsson S (2015) A person-centred approach to health promotion for persons 70+ who have migrated to Sweden: Promoting aging migrants' capabilities implementation and RCT study protocol. BMC Geriatrics 15(1).

- Synneve Dahlin-IvanoffEmail author, Gunilla Gosman Hedstrom, Anna Karin Edberg, Katarina Wilhelmson, Kajsa Eklund, et al. (2010) Elderly persons in the risk zone. Design of a multidimensional, health-promoting, randomised three-armed controlled trial for "prefrail" people of 80+ years living at home. BMC geriatrics 10(1):

- Gustafsson S, Lood Q, Wilhelmson K, Haggblom-Kronlof G, Landahl S, et al., A person-centred approach to health promotion for persons 70+ who have migrated to Sweden: promoting aging migrants' capabilities implementation and RCT study protocol. BMC geriatrics 15(1): 10.

- Wilhelmson, Katarina, Duner, Anna, Eklund, et al. (2011) Continuum of care for frail elderly people: Design of a randomized controlled study of a multi-professional and multidimensional intervention targeting frail elderly people.

- Folstein MF, SE Folstein, PR McHugh (1975) "Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3): 189-198.

- Ware J (1993) SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide (The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts). Google Scholar.

- Shankar A, SB Rafnsson, A Steptoe (2015) Longitudinal associations between social connections and subjective wellbeing in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychology & health 30(6): 686-698.

- Biggs JT, LT Wylie, VE Ziegler (1978) Validity of the Zung self-rating depression scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry 132(4): 381-385.

- Gottfries G, S Noltorp, N Norgaard (1997) Experience with a Swedish version of the Geriatric Depression Scale in primary care centres. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 12(10): 1029-1034.

- Santiago LM, IE Mattos (2014) Depressive symptoms in institutionalized older adults. Revista de saude publica 48(2): 216224.

- Litwin H (2006) Social Networks and Self-Rated Health A Cross- Cultural Examination Among Older Israelis. J Aging Health 18(3): 335-358.

- Rosenquist JN, JH Fowler, NA Christakis (2011) Social network determinants of depression. Mol Psychiatry 16(3).

- Ross CE, J Mirowsky (1989) Explaining the social patterns of depression: control and problem solving--or support and talking? J Health Soc Behav 30(2): 206-119.

- R Khairudin, R Nasir, AZ Zainah, Y Fatimah, O Fatimah, et al., Depression, anxiety and locus of control among elderly with Dementia. 19: 27.

- Tsai YF (2005) Comparison of the prevalence and risk factors for depressive symptoms among elderly nursing home residents in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20(4): 315-321.

- Depression is not a normal part of growing older. Healthy Aging.

- Hooyman NR, HA Kiyak (2008) Social gerontology: A multidisciplinary perspective. Pearson Education.

- Goosby BJ (2013) Adolescent loneliness and health in early adulthood. Sociological inquiry, 2013. 83(4): 505-536.

- Lim LL, EH Kua (2011) Living alone, loneliness, and psychological well-being of older persons in Singapore. Current gerontology and geriatrics research.

- Cheng ST, HH Fung, A Chan (2009) Self-perception and psychological well-being: the benefits of foreseeing a worse future. Psychol Aging 24(3): 623-633.

- Chou KL, I Chi (2000) Comparison between elderly Chinese living alone and those living with others. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 33(4): 51-66.

- Mui AC (1996) Depression among elderly Chinese immigrants: An exploratory study. Social Work 41(6): 633-645.

- Chou KL, A Ho, I Chi (2006) Living alone and depression in Chinese older adults. Aging and Mental Health 10(6): 583-591.

- Mellor D (2008) Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and individual differences 45(3): 213-218.