Effect of Medical Student Perception of Older Adults: A Two Year Experience

Gerard Kerins*1, Jack Contessa2 and Chandrika Kumar3

1Yale School of Medicine, Program Director, Geriatric Fellowship, Yale New Haven Hospital, USA

2Yale New Haven Hospital, USA

3Yale School of Medicine, USA

Submission: September 09, 2017; Published: September 12, 2017

*Corresponding author: Gerard Kerins, Yale School of Medicine, Program Director, Geriatric Fellowship, Yale New Haven Hospital, USA; Email: Gerard.kerins@ynhh.org

How to cite this article: Gerard K, Jack C, Chandrika K. Effect of Medical Student Perception of Older Adults: A Two Year Experience. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2017; 2(3): 555588 DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2017.02.555588

Introduction

The model of creating a nursing home-medical school affiliation to teach medical students was a unique and new concept in the 1980's. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Institute on Aging provided support and impetus to several of these innovative teaching nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities to partner with medical schools. The idea began to gain momentum in the 1980-1990's and this model of teaching continues to be sustained today by many medical schools and academic medical centers despite the scarcity of outcome data about students' experiences.

Sustaining this model so that medical students develop a good understanding about caring for older adults is imperative since according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services the population of older adults - 65 years or older represent 14.1% of the U.S. population, or about one in every seven Americans. By 2040 this number is expected to grow to approximately 80 million or 21.7% of the population.2,3 Additionally, care for this population will continue to be provided by Primary Care and family medicine physicians, many of which are non-geriatricians.4As such, long term care facilities are potentially effective venues for teaching and learning since patients display a wide spectrum of syndromes including a high prevalence of dementia, delirium, and depression in the cognitive domains and falls/mobility issues in the functional domains. Polypharmacy, multiple co morbidities, goals of care, and nutrition are the other common geriatric issues found in the long term care settings.

Keywords: Medical Students; Functional Assessment; Activities of Daily Living; Cognitive Assessment; Geriatrics; Perceptions

Curricular Design

Our geriatric curriculum was designed to incorporate learning experiences in long term care facilities for the same cohort of medical students at the Yale School of Medicine during their first and second years as a prelude to their clerkship years. Curricular activities comprised a one half-day session in each of the two years. Given the limited time available, the geriatric clinician educator faculty members decided to focus on teaching functional assessment skills the initial year to first year medical students and cognitive assessment skills the second year. Next, the faculty decided on the most appropriate type of facility to teach each of these skill sets. Feedback was obtained from geriatric faculty who served as medical directors in several different types of facilities. The facility that was best suited for teaching functional skills was a continuing care retirement community where many of the older adults lived in their own apartments requiring some help in Activities of Daily Living ( ADL's) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL's). A long term care facility was best suited to teaching second year medical students’ cognitive assessment skills [1].

Logistics, Planning and Implementation

Medical Directors of these two types of facilities were contacted to solicit their support and to select residents she/he thought would be ideal candidates for having their function and cognition assessed by medical students once a group of potential candidates was identified, each candidate was contacted by the facility's Medical Director or a staff member to determine if she/ he would be willing to volunteer and have medical students interview and examine them. When the requisite number of residents was reached and consent obtained, the facility was contacted to arrange dates and times for the medical students' visits. Several days prior to the date of the visit geriatric faculty/ geriatric medicine fellows, who were previously chosen as preceptors for this study, were emailed printouts of the cognitive and functional tests. Preceptors were directed to teach students how to implement the function assessment test and observe students as they administered them. On the day of the visit, students were transported to the facilities and given a 15 minute overview about the organization along with details regarding the assessments they would be using. The students were then divided into groups of 4-5 each with one preceptor.

Each student team and preceptor visited two patients in their home environment (apartment) in either the continuing care retirement community or long term care facility. Students assessed [2-5] patients so that each would have ample time to observe and carry out the assigned tasks. After the preceptor introduced the student team to the residents, students took turns conducting the functional assessments. Each resident visit took approximately 30-45 minutes, and provided a sufficient amount of time for students to complete their assessments. Gait assessment and timed up-and-go were the two physical examinations done on the residents by the first year students and questions were asked on ADL's and IADL's. A similar process was used the following year with the second year medical students administering SLUMS (St. Louis mental status examination) [5] to assess cognition.

Each year after the small groups completed both visits, preceptors discussed with them interpretation of their findings on the physical and cognitive exams and provided feedback. Preceptors also asked them to describe their most meaningful experience and their most memorable observation. All sessions ended in a debriefing activity where students shared their observations with the entire group.

Results

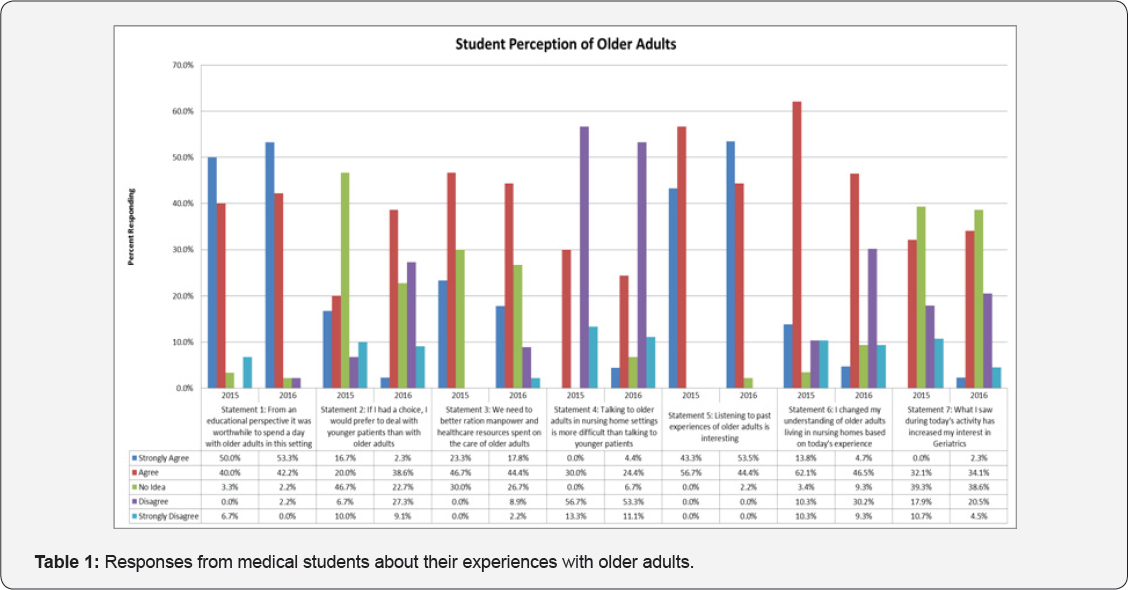

The same seven question survey was administered each year (2015, 2016) to the same group of medical school students in their first and second academic years after they participated in the curricular activities. Students responded to these statements on a five point Likert Scale, which ranged from "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree". (See Table 1) Answers were compared between these two groups to determine if there were differences or congruence in how the same students responded to the same statements from one year to the next (Table 1).

Data in Table 1 indicate significantly more students the second year (36% vs. 17%) "Disagreed" or "Strongly disagreed" that they would prefer to deal with younger patients than with older adults (Statement 2). It seems that having additional exposure to working with older adults gave students more confidence and comfort to have them as patients [3].

Additionally, student understanding of older adults (Statement 6) changed significantly based on their encounters during the initial visit in 2015. 76% of students that year responded they "Strongly Agreed" or 'Agreed" with this statement. Interestingly, in 2016 over 50% of this same group "Strongly Agreed" or "Agreed" with this statement. It's likely that over the intervening year between visits a number of students lost sight of their perceptions from the previous year. This seems to indicate more frequent encounters, encounters of longer duration, or both should be scheduled for students to better retain what they observed and learned.

During both years approximately one-third of students "Agreed" that their interest in Geriatrics was enhanced (Statement 7) while about 40% weren't sure. Similar to the recommendation above, more experiences with older adults or experiences of longer duration could help crystallize interest for those students who were not sure [4].

Discussion

The educational value of having medical students interacting and spending time with older patients early in their training has been documented. Specifically, our efforts resulted in, among other outcomes, better understanding of the practical application of functional and cognitive screening tools in older adults and increased interest in the field of geriatrics. The value of knowing and practicing these screening tools helps students recognize the difference between what many expected based on prior conceptions of the older adults and what they ultimately came to realize is older adults' actual cognitive and functional capability. As a result, this underscores the importance of medical students interacting with older adults and learning how to administer cognitive and functional screening skills early in their medical school experience.

As their training progresses, and as they come to experience a wider variety of clinical settings, students will demonstrate an even greater appreciation of such assessments Even in these introductory sessions, students became more comfortable interacting with older adults and demonstrating the ability to ask "the right questions."

In addition to the educational outcomes derived in these sessions, the value students expressed from listening to older adults' life experiences cannot be overstated. This was clearly evident at the debriefing sessions held at the end of each workshop. Many students commented that they previously had little opportunity to interact with older adults at this stage of their training. Among the numerous positive comments that were generated were statements about how this experience, even at this level and for this short amount of time, helped to make them better listeners. Lastly, students commented that after completing these sessions with older adults, they would be more receptive to considering careers in geriatrics and geriatrics-related fields.

There are some limitations to the study. It is a two year single institution study and the facilities chosen were where geriatricians served as medical directors. Although there was a change in attitude immediately after these sessions, whether this is sustained through their clerkship years and residency training will require a more prolonged observation and different measurement tools.

Appreciating the unique position that older adults play in our healthcare delivery system can only be further enhanced when students begin to learn the art and science of caring for such a special population early in their training. More research is needed to assess the long-term effect of such workshops on students' interactions with older adults in a variety of clinical settings and career choices.

Conflict of Interest

There is no economic interest or conflict of interest for any of the three authors: Gerard Kerins, MD Jack Contessa PhD, Chandrika Kumar MD.

References

- Weiler PG (1987) The teaching nursing home as an academic program. Edu Gerontol 13: 1-13.

- https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf- accessed online May 2017

- US Census Bureau (2009) Age Data of the United States 2008 & State and County Quick Facts, 2008” Washington, DC, 2009 GPO.

- Raji MA (2008) Geriatrics in Primary Care Residency Training. 10(6): 375-378.

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, Morley JE, et al. (2006) Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder-- a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(11): 900-910.