- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Health Care Use in the Randomized Controlled Trial “Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People”

Katarina Wilhelmson1,2,3’, Kajsa Eklund1,3, Sten Landahl1,3, Synneve Dahlin Ivanoff1,3

1Department of Health and Rehabilitation, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, The Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

2Department of Geriatrics, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

3Centre of Aging and Health-AgeCap, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Submission: August 25, 2017; Published: August 31, 2017

*Corresponding author: Katarina Wilhelmson, Department of Health and Rehabilitation, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, Email: katarina.wilhelmson@gu.se

How to cite this article: Wilhelmson K, Eklund K, Landahl S, Dahlin Ivanoff S. Health Care Use in the Randomized Controlled Trial “Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People”. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2017; 2(3): 555587 DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2017.02.555587

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Abstract

Dependence in the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) is associated with increased health care consumption. This study aimed to determine if an intervention involving a continuum of care for frail elderly people reduced the use of in-hospital and outpatient care; and if healthcare use differed by subgroups based on ADL dependence.

This was a non-blinded randomized controlled trial. Participants (n=161) were aged 65-79 years with at least one chronic disease, and dependent in at least one activity of daily living (ADL); or aged 80+ years; and sought care at the emergency department. Exclusion criteria were immediate need of assessment and treatment by a physician, severe cognitive impairment, and palliative care. The intervention involved collaboration between a nurse with geriatric competence based in the emergency department, hospital wards, and a municipality-based multiprofessional team with a case manager that provided care for the elderly people, care planning in the home, and active follow-up. Participants were divided into subgroups based on ADL dependence during the analysis. In the intervention group, participants classified as independent in ADL had fewer visits to a physician compared with the control group. The intervention group received more home visits by occupational therapists/physiotherapists, probably attributed to the rehabilitation inherent to the intervention. Time to first readmission was almost twice as long for independent participants in the intervention group compared with the control group (not statistically significant). Further research with a larger sample size and longer follow-up is needed to confirm if the intervention also reduces in-hospital care.

Keywords: Frail elderly, intervention study, randomized controlled trial, healthcare consumption, activities of daily living

Abbreviations: RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial; ADL: Activities Of Daily Living; ED: Emergency Department

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Introduction

Frail elderly people are at high risk for developing chronic diseases, multi-morbidity, and functional impairments. In many cases, this leads to dependence in the activities of daily living (ADL) [1-3]. Dependence in ADL is associated with increased healthcare consumption, including in-hospital care and outpatient visits [4-9]. Deterioration in ADL is common before and during hospital stays, especially among older patients. This leads to many older patients being less able to perform ADL when discharged from hospital than they were before the onset of their acute illness [10]. The oldest patients are also less likely to recover this lost ADL ability, and are at risk of developing new functional deficits during their hospital stay [10]. Therefore, actions that lead to elderly people maintaining or improving their ADL ability have the potential to reduce the need for health and social care.

A review of outpatient case management by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found limited impact on patient-centered outcomes, quality of care, and resource use for patients with chronic illness. However, for frail elderly people they state that case management programs have potential to help avoid or reduce functional loss, improve quality of life, maintain independence, and may also forestall hospitalizations, Emergency Department (ED) visits, and skilled nursing facility use [11]. This may be accomplished through coordinating care for complex illnesses, and preventing adverse events and disease exacerbations. A recent systematic review of the effect of personal case managers for the frailest elderly people by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare found moderate evidence that the mean hospital stay was reduced by almost 2 days over a 1-year period, and low evidence for a reduced risk of being hospitalized over a 6-month period [12]. An integrated approach across hospital and community settings is needed to reduce unnecessary use of hospital beds by elderly people.

Reviews of randomized controlled trials on integrated and coordinated interventions targeting frail elderly people living in the community found that some studies reported reduced healthcare use, whereas others reported no effect [13,14]. Another review of clinical trials (randomized or controlled) that aimed to reduce readmissions in older patients showed that three of 17 in-hospital interventions and seven of 15 interventions with home follow-up had a positive effect on readmission. They concluded that interventions with home care components seemed more likely to reduce readmissions in elderly people [15]. Single-component interventions are unlikely to significantly reduce readmissions, and the effect on readmission rates is related to the number of components included in the intervention [16].

The study "Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People” involved a complex intervention that aimed to create a continuum of care for elderly people from the ED to their own homes [17]. The intervention included home care components such as a community-based case manager supported by a multiprofessional team, and active follow-ups by the case manager. Earlier publications on the study have reported positive effects on ADL [18], satisfaction with care [19], and life satisfaction [20], but no effect on frailty status [18]. Frailty was in this study defined based on the frailty phenotype by Fried et al [21], with the addition of impaired cognition, balance and sight, with 3 or more criteria indicating frailty and 1-2 criteria pre-frailty. As dependence in ADL is known to have impact on health care utilization and the intervention had effect on ADL, we found it worthwhile to analyze if the health care use differed between intervention and control groups in the complex intervention "Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People”

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Material and Methods

The aim of this study was to determine if the intervention "Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People” could reduce the use of in-hospital and outpatient care, and if healthcare use differed by ADL dependence.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Study Design

The study was a randomized controlled trial, with one intervention group and one control group. Follow-ups were conducted at 3, 6, and 12 months. The study was not blinded, as most participants revealed their group allocation at the follow- ups, and to allow the same research assistant to be present at the different follow-ups to minimize attrition. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, ref no 413-08, and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01260493. All participants provided written informed consent.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Participants and Setting

The study population included 161 elderly people who received ED care at Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Molndal from October 2008 to June 2010, and who were discharged to their own homes in the municipality of Molndal, Sweden [17]. Inclusion criteria were people who were aged 65-79 years with at least one chronic disease, and dependent in at least one ADL; or people aged 80 years and older. Exclusion criteria were immediate need of assessment and treatment by a physician, severe cognitive impairment (i.e. dementia according to medical records or obvious severe cognitive impairment as judge by the nurse with geriatric competence), and palliative care [17].

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Intervention Group

The intervention involved collaboration between a nurse with geriatric competence based in the ED, the hospital wards, and a municipality-based multi-professional team with a case manager to provide care for participating elderly people. The multi-professional team included professionals with university degrees in nursing (the case manager), social work, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy. The intervention aimed to create a continuum of care from the ED, through the hospital ward, to the participants' own homes. In addition, support for relatives was initiated during the hospital stay.

The nurse assessed the elderly patients need for rehabilitation, nursing, geriatric, and social care. This assessment was transferred to the ward and to the municipality-based case manager. The case manager then contacted the ward and the patient to initiate discharge planning. Discharge planning involved collaboration between the case manager, a social worker, the patient, and the nurse and physician in charge on the ward. Patient care planning was conducted in the participant's home within a couple of days after discharge. Patient care planning was performed in the same way for patients that were discharged directly from the ED. The multi-professional team was responsible for the patient care planning, and involved the patient throughout the intervention. The patient care planning was based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment of the participants' needs of care, rehabilitation and follow up, and was performed by the team, followed-up after 1 week by the case manager, and then followed-up least every month. The elderly people were included in the intervention for at least 1 year.

With the participants' approval, the case manager contacted the participants' relatives/informal caregivers, to provide information, involve them in care planning, and offer support and advice. This was initiated as soon as possible, often as early as when the participant was in hospital.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Control Group

The control group received conventional care and follow- up. Access to a case manager or multi-professional team was not part of the present organization of municipal care for elderly people living in Molndal. Conventional patient care planning was performed at the hospital by a community team comprising different professional groups (social workers, nurses, and occupational therapists or physiotherapists), if needed. After discharge, another municipality elderly care team was responsible for the follow-up of the care planning. If the patient was discharged from the ED directly to their home, there was no routine information transfer from the hospital to the municipality. In the present study, in addition to conventional care for the control group, assessments were performed at the research follow-ups, as for the intervention group (see the procedure below). If unmet needs were identified at these research follow-ups, the participant was given advice on where and how to seek help.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Procedure

Participants were recruited by the nurse with geriatric competence based in the ED. Elderly patients were screened to determine if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. If so, the nurse provided verbal and written information about the study, including a description of the study, how it would be conducted, and what was expected of people who agreed to participate. Patients were given opportunities to ask questions if anything was unclear. The verbal and written information emphasized that participation was voluntarily. People who agreed to participate in the study were randomized to the intervention or control groups using a system of sealed opaque envelopes. All participants signed a written consent form.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

A baseline interview and assessment were performed within a week of discharge. In some cases, it was not possible to complete the baseline interview so soon, mostly because the participant did not have enough strength. Baseline interviews for the intervention group were conducted by the multi-professional team as part of their comprehensive geriatric assessment. The baseline interviews for the control group were conducted by a research assistant (occupational therapist, nurse, or social worker). The interviews were performed in the participants' homes. All interviewers were well trained in interviewing, assessing, and observation, according to the guidelines for the different outcome measurements. Meetings were held regularly with all personnel in the intervention, starting 1 month before starting the recruitment process and continuing throughout the intervention period [17].

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

ADL was assessed at baseline. The degree of dependence in ADL was measured using the ADL staircase [22]. This measures independence of, or dependence on, another person in five personal ADL items (bathing, dressing, going to the toilet, transferring, and feeding). Katz et al. [23] extended the staircase with four instrumental items (cleaning, shopping, transportation, and cooking). Dependence was defined as a state in which another person was involved in the activity by giving personal or directive assistance. The validity and reliability of the ADL staircase are good for the age group in the present study [24,25]. A participant was considered to be dependent if they were dependent in at least one activity, otherwise they were considered to be independent.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Healthcare Use

Information on healthcare use for 1 year after enrollment in the study was retrieved from VEGA, the regional care database, and included in-hospital and outpatient care, visits to primary healthcare (physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses, and assistant nurses), and home visits by primary healthcare professionals. The number of readmissions, number of in hospital days, time to first readmission, and number of outpatient visits were calculated for 1 year after study enrollment. If a participant had been cared for in more than one ward during their hospital stay without discharge in between, this was considered to be one hospital stay.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Sample Size

A power calculation was done for the main study, based on the Berg balance scale (one of the frailty indicators, range 0-56), with an assumed mean for the intervention group of 32 and for the control group of 28 (15% difference), and a standard deviation of 8 in both groups. To be able to detect a difference between the intervention and control groups with a two-sided test and with a significance level of alpha= 0.05 and 80% power we would need at least 65 people in each group, see also the study protocol [17].

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Statistical Analyses

The outcomes were analyzed using chi-square or students t-tests for between-group comparisons. Two-sided significance tests were used throughout, and a p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with PASW Statistics, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Results

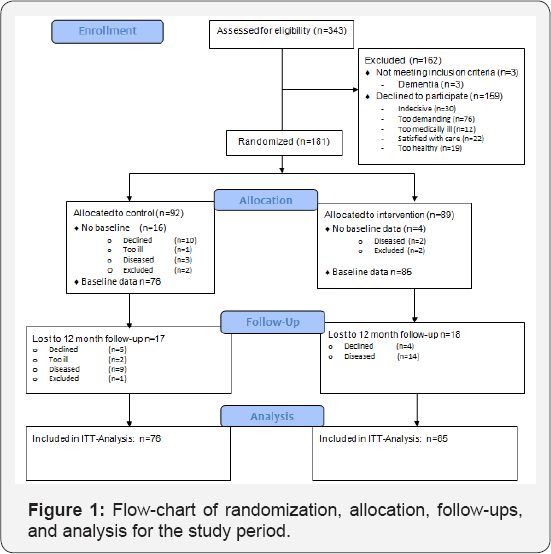

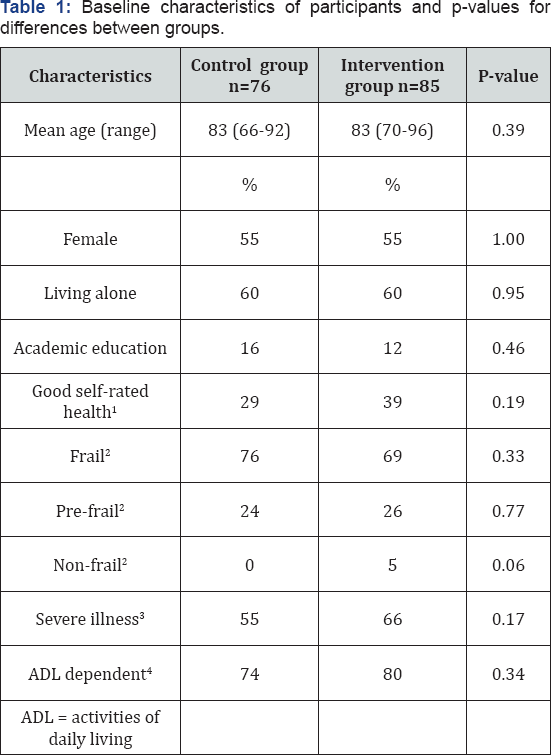

During the recruitment period, 343 elderly people met the inclusion criteria and were asked to participate. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants according to the CONSORT diagram. Of these, 159 declined to participate and an additional three people did not meet the inclusion criteria when further investigated. Therefore, 181 participants who consented to participate were randomized. Twenty people did not participate in the baseline assessment, leaving data for 76 participants in the control group and 85 in the intervention group for analysis. There were no statistically significant differences in the characteristics of participants in the two groups at baseline. There were more participants in the intervention group that died during the one year follow up, 14 compared to 5 in the control, see Figure 1, not statistically significant (p=0.052). Therefore, we also analyzed the health care consumption for survivors, with similar results as for the whole group (data not shown) (Figure 1), (Table 1).

_________________________________________________________________

1Answered excellent, very good, or good to the question “In general, would you say your health is?”

2Frail=Fullfilled at least three of the following indicators: weakness (grip strength of less than 13 kg for women and 21 kg for men for the dominant hand and 10 kg for women and 18 kg for men for the non-dominant hand, measured using a hand dynamometer) fatigue (answered yes to the question: “Have you suffered any general fatigue or tiredness over the last three months?”), weight loss (yes to the question: “Have you suffered from any weight loss over the last three months?), low physical activity (one to two walks per week or less), poor balance (a score of 47 or lower on the Berg balance scale), reduced gait speed (walking four meters in 6.7 seconds or slower), visual impairment (visual acuity of ≤0.5 in both eyes measured with the KM chart), and impaired cognition ( < 25 points in the Mini Mental State Examination). Pre-frail=fulfilling 1-2 indicators. Non-frail= not fulfilling any indicator (for details, see study protocol[17].

3At least one score of 3 or 4 on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics [17].

4Dependent in at least one ADL.

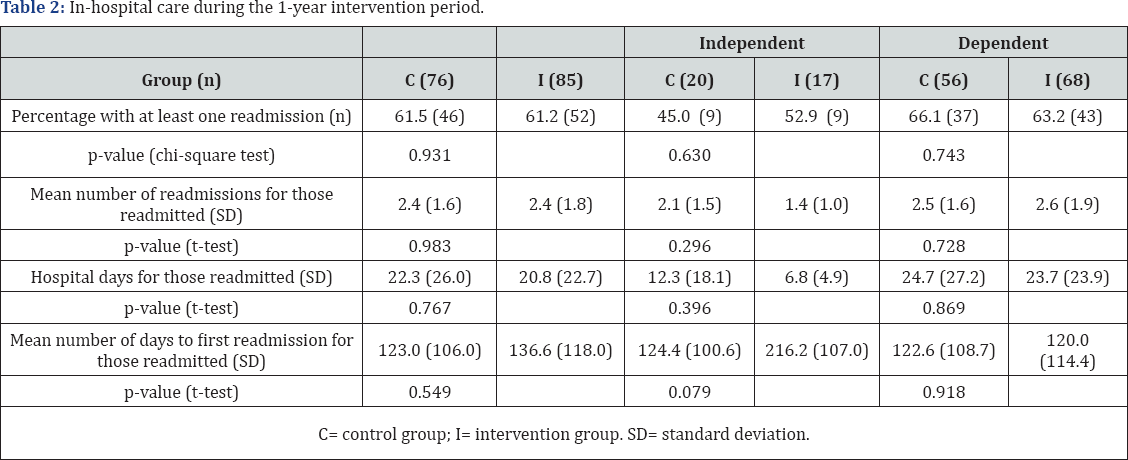

In-hospital care consumption in the 1 year following recruitment is shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups in the proportion of participants readmitted, mean number of readmissions, or number of hospital days for those readmitted. For participants in the intervention group who were independent in ADL, there was a trend toward fewer admissions (not statistically significant). In addition, independent participants in the intervention group had almost half the number of in-hospital days compared with independent participants in the control group (not statistically significant). The intervention group also had more days to the first readmission (not statistically significant). This difference was most pronounced for independent participants (124 vs. 216 days to readmission) (Table 2).

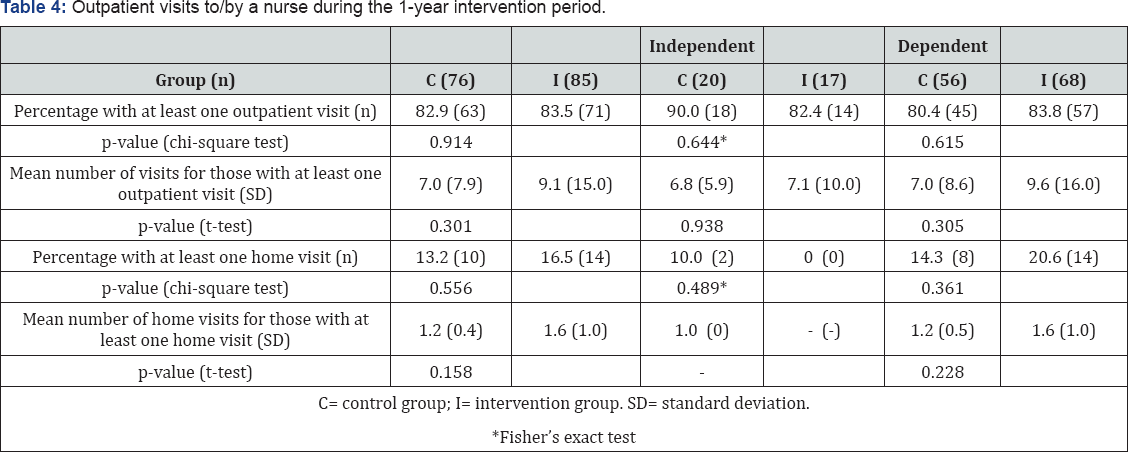

We found few statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups for outpatient care. In total, 98.7% participants in the control group and 91.8% in the intervention group had at least one visit to a physician, with no statistically significant difference between the groups. Among those with at least one outpatient visit to a physician, independent participants in the control group had a mean number of three more visits to a physician compared with the intervention group (p=0.050). Home visits by a physician were less common, with the proportion of participants receiving at least one visit ranging from 10% to 33.8% (Table 3).

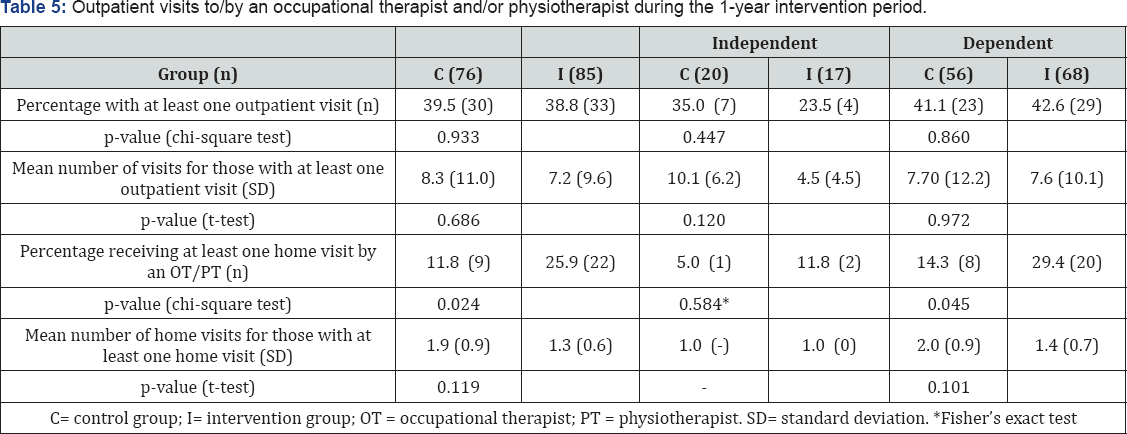

There was a trend toward more visits to/by a nurse in the intervention group, but this was not statistically significant. There was a statistically significant higher proportion receiving at least one home visit by occupational therapists and/or physiotherapists in the intervention group, particularly for those dependent in ADL. There was an opposite trend for independent participants, although this was not statistically significant (Tables 4 & 5).

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial involved a complex intervention that included a nurse with geriatric competence based in the ED, and active follow-up by a case manager with support from a multi-professional team in the municipality. The intervention did not show a significant reduction in the use of in-hospital care. There was a significant difference in outpatient care consumption, with fewer visits to a physician for those in the intervention group who were independent in ADL compared with the control group. There were also more home visits by occupational therapists/physiotherapists in the intervention group, most pronounced for participants who were dependent in ADL. In addition, there were differences in healthcare use between the groups in favor of the intervention group that are worth noting, even if they were not statistically significant. For example, the time to first readmission was almost twice as long for independent participants in the intervention group compared with the control group.

It is hard to know if the lack of significant results is due to the intervention being insufficient or if the major limitation is lack of power. The power calculation was performed on physical function using the Berg balance scale [17] and not on healthcare use, and the analysis in this study is on secondary outcomes. In addition, the heterogeneity of the sample and the high standard deviation for healthcare use probably require a larger sample. There were indications of lower use of hospital care in independent participants in the intervention group, especially a longer time to readmission, but these were not statistically significant. With a larger sample, it might have been possible to show significant effects.

A review of randomized controlled trials with integrated and coordinated interventions targeting frail elderly people living in the community found that two of nine studies had a statistically significant effect on hospital/ED use in favor of the intervention, one study was in favor of control, and four studies showed a statistically significant effect on hospital days in favor of the intervention. Therefore, as with our study, several other studies have had difficulty showing significant effects on healthcare use.

The randomized controlled trial "Continuum of care” is a complex, community-based intervention, as were the studies included in the review and meta-analysis by Beswick et al. [14] . That review found a reduction in the risk of hospital admission, especially for interventions including geriatric assessment in frail elderly people and community-based care after hospital discharge. It is contradictory that our study did not find a reduced risk of hospital admissions. Beswick et al. noted that the benefits were most evident in studies started before 1993, and stated that the care had probably improved since 1990 [14]. Therefore, a reason why our study showed few statistically significant effects on healthcare consumption might be that the control group received good enough care, and thereby the improvement achieved by the intervention was not enough to show a difference [26]. In addition, the nurse with geriatric competence, the multi-professional team, and the follow-ups by the case manager might have led to the discovery of unmet needs requiring healthcare, resulting in a higher demand for healthcare in the intervention group.

As almost always in complex interventions - which are needed to meet the complex and heterogenetic needs of frail elderly people - it is difficult to know what parts of the intervention might have been successful in meeting the needs. There are indications that models with established and integrated teams in the older people's home are most effective in preventing older adults' hospital admission when they include geriatric assessments, care planning, and continuity in care transitions, disease management, and health promotion [27]. Our study included many of these aspects, but lacked a clear focus on disease management and health promotion, which might explain why our study showed few statistically significant differences between the groups on the use of hospital care. However, those independent in ADL had a longer mean time to first readmission with over 90 days for the intervention group compared with the control group.

Case management, a central part of the intervention in this study, has been found to reduce healthcare consumption in some studies but has failed to do so in other studies [28,29]. Studies showing positive effects on healthcare consumption such as those by Bird et al. [30,31] were not randomized controlled trials; instead they compared healthcare use before and after an intervention. A recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials of effect on unplanned hospital admission for older people concluded that nine of 11 trials showed no reduction, and stated that the review provided evidence that case management did not reduce unplanned hospital admissions for elderly people [26]. In our study, we did not differentiate between planned and unplanned readmissions. However, a manual review of the readmissions in the participants' hospital records showed that few readmissions were planned (less than 15%); therefore, our results are comparable with those reported in the review by Huntley et al. [26]. The randomized controlled trial with the most pronounced effect on healthcare consumption in that review was a study reported by Naylor et al. in 1999 [28] which found fewer readmissions, fewer hospital days, and longer time to first readmission. Compared with our study, that study had a larger sample size, lower median age, a shorter and more intense intervention, and a shorter follow-up period. Therefore, there are several discrepancies between the studies that might influence the outcomes.

Early discharge planning, another central part of the intervention in this study, has previously been shown to be associated with fewer hospital readmissions and a lower readmission length of hospital stay in a meta-analysis of randomized control and quasi-experimental trails with parallel controls by Fox et al. [32]. Again, lack of power might be the reason why our study failed to show a statistically significant impact on hospital use. On the other hand, our intervention had a positive impact on the participants' satisfaction with discharge planning [19], which is contrary to the results of the metaanalysis by Fox et al. [32].

A limitation of our study is that the baseline data for the intervention group was measured by the municipality-based team, while the control group was interviewed and measured by project assistants. This might have led to different ratings on, for example, ADL and frailty status in the two groups. However, we had regular meetings with all interviewers throughout the project to discuss assessments and ratings, in order to minimize differences between interviewers. In addition, all variables concerning ADL and frailty has carefully been reviewed by at least two of the authors (KE and SDI for ADL; and KE and KW for frailty), in order to minimize any differences in assessment leading to bias. One might also criticize that we did not have at least one dependence in ADL or one chronic disease as inclusion criteria for all age groups, leading to inclusion of people with no ADL dependence and no chronic diseases. However, the fact that they were aged >80 years, and in need of care at the ED, indicates that they were a vulnerable group, and only four people were non-frail at baseline. Many of those not fulfilling three or more frailty criteria or who were independent in ADL at baseline developed frailty or dependence during the 1-year follow up [18].

There were more participants in the intervention group that died during the follow-up period (n=14) compared with the control group (n=5), but this was not statistically significant. Healthcare consumption is highest the last year before death [33]. Therefore, a difference in the number of deceased participants might give a higher healthcare use in the intervention group, and make it more difficult to detect a possible decrease in the intervention group. However, we also analyzed the healthcare consumption only for survivors (data not shown) and found similar and not statistically significant results.

The increased use of home visits by occupational therapists/ physiotherapists is expected, as early identification of rehabilitation needs was a core element of the intervention. Therefore, this finding may show the intervention performed as intended. That the intervention was successful in providing rehabilitation to participants is also supported by the finding that the intervention reduced dependence in ADL, as reported earlier [18]. In the study by Naylor et al., there was no difference between intervention and control groups in home visits by occupational therapists or physical therapists, and the intervention had no effect on mean functional status [28]. On the other hand, in our study, there was no difference in home visits by a nurse, which contrasted with the study by Naylor et al. where the intervention group had fewer home visits by a nurse. In our study, the independent participants in the intervention group had statistically fewer visits to a physician compared with the control group. This is consistent with another Swedish study involving case management, which found a lower number of outpatient visits to physicians in the intervention group as well as a lower number and proportion of ED visits not leading to hospitalization. However, these three results were the only significant findings from over 50 analyses and must be interpreted with caution because there was no adjustment for multiple analyses as must our finding of fewer visits to a physician that just reached statistical significance.

We found a trend towards a longer time to first readmission and fewer in-hospital days, as well as statistically significantly fewer visits to a physician for independent participants in the intervention group compared with the control group. This might indicate that the intervention involving a case manager and active follow-ups had an effect on healthcare use among participants who were independent in ADL but not those who were dependent. The fact that the intervention had a positive impact on ADL [18] may indicate a positive effect on healthcare use over a longer time period, as ADL is associated with healthcare use [4-8]. In addition, our intervention included a home-based assessment by the multi-professional team, which enhanced the possibility of acknowledging rehabilitation needs to support participants' independence in ADL and remaining in their home. We believe that this assessment was one reason why more participants in the intervention group received visits by occupational therapists/physiotherapists which possibly led to the positive effects on ADL in this group [18], with the potential to reduce future healthcare use. The association between functional impairment and increased risk of readmission was recently reported by Greysen et al., who concluded that functional impairment may be an important factor in preventing readmissions.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Conclusion

To summarize, significant differences in healthcare use between intervention and control group were few, and none for in-hospital care. Subgroup analyses showed that independent participants who received the intervention "Continuum of Care for Frail Elderly People” had fewer outpatient visits to a physician compared with the control group. There was a trend, not statistically significant, toward a longer time to first readmission for the intervention group. The intervention group received significantly more home visits by occupational therapists/physiotherapists, which might have been due to the rehabilitation inherent in the intervention. Further research with a larger sample size and longer follow-up period is needed to confirm if this kind of intervention reduces healthcare use.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Acknowledgement

The authors especially thank Ann-Charlotte Larsson for her engagement in the implementation of the continuum of care chain, and the elderly study participants. The study is financed by external grants from The Vardal Institute, The Vardal Institute, the Swedish Institute for Health Sciences the Vardal Institute, the Swedish Institute for Health Sciences Vinnvard and Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (AGECAP 2013-2300).

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Material and Methods

- Study Design

- Participants and Setting

- Intervention Group

- Control Group

- Procedure

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Activities Of Daily Living (ADL)

- Healthcare Use

- Sample Size

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References

References

- Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, Fried LP, et al. (2004) Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(4): 625-634.

- Gill TM (2005) Education, prevention, and the translation of research into practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4): 724-726.

- Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, Peduzzi PN, et al. (2002) A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med 347(14): 1068-1074.

- Chan L, Beaver S, Maclehose RF, Jha A, et al. (2002) Disability and health care costs in the Medicare population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 83(9): 1196-1201.

- Landi F, Onder G, Cesari M, Barillaro C, et al. (2004) Comorbidity and social factors predicted hospitalization in frail elderly patients. J Clin Epidemiol 57(8):832-836.

- Philp I, Mills KA, Thanvi B, Ghosh K, et al. (2013) Reducing hospital bed use by frail older people: results from a systematic review of the literature. Int J Integr Care 13: e048.

- Preyde M, Brassard K (2011) Evidence-based risk factors for adverse health outcomes in older patients after discharge home and assessment tools: a systematic review. J Evid Based Soc Work 8(5): 445-468.

- Robinson S, Howie-Esquivel J, Vlahov D (2012) Readmission risk factors after hospital discharge among the elderly. Popul Health Manag 15(6): 338-351.

- Sandberg M, Kristensson J, Midlov P, Jakobsson U (2015) Effects on healthcare utilization of case management for frail older people: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 60(1): 71-81.

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, et. al. (2003) Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(4): 451-458.

- Hickam DH, Weiss JW, Guise JM, Buckley D, Motu'apuaka M et al. (2013) Outpatient Case Management for Adults With Medical Illness and Complex Care Needs [Internet].

- The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (2013) The effects of personal case managers for the frailest elderly people - a systematic review.

- Eklund K, Wilhelmson K (2009) Outcomes of coordinated and integrated interventions targeting frail elderly people: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Health Soc Care Community 17(5):447-458.

- Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, Ayis S, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. (2008) Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Lancet 371(9614): 725-735.

- Linertova R, Garcia-Perez L, Vazquez-Diaz JR, Lorenzo-Riera A, et al. (2011) Interventions to reduce hospital readmissions in the elderly: in-hospital or home care. A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 17(6): 1167-1175.

- Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE (2014) Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med 65: 471-485.

- Wilhelmson K, Duner A, Eklund K, Gosman-Hedström G, Blomberg S et al. (2011) Design of a randomized controlled study of a multiprofessional and multidimensional intervention targeting frail elderly people. BMC Geriatr 11: 24.

- Eklund K, Wilhelmson K, Gustafsson H, Landahl S, et al. (2013) One- year outcome of frailty indicators and activities of daily living following the randomised controlled trial: Continuum of care for frail older people. BMC Geriatr 13:76.

- Berglund H, Wilhelmson K, Blomberg S, Duner A, et al. (2013) Older people's views of quality of care: a randomised controlled study of continuum of care. J Clin Nurs 22(19-20): 2934-2944.

- Berglund H, Hasson H, Kjellgren K, Wilhelmson K (2015) Effects of a continuum of care intervention on frail older persons' life satisfaction: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Nurs 24(7-8): 1079-1090.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, et al. (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56(3): M146-156.

- Jakobsson U (2008) The ADL-staircase: further validation. Int J Rehabil Res 31(1): 85-88.

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW (1963) Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185(12): 914-919.

- Sonn U (1996) Longitudinal studies of dependence in daily life activities among elderly persons. Scand J Rehabil Med Suppl 34:1-35.

- Sonn U, Asberg KH (1990) Assessment of activities of daily living in the elderly. A study of a population of 76-year-olds in Gothenburg, Sweden. Scand J Rehabil Med 23(4):193-202.

- Huntley AL, Thomas R, Mann M, Huws D, Elwyn G, et al. (2013) Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract 30(3): 266-275.

- Batty C (2010) Systematic review: interventions intended to reduce admission to hospital of older people. Intern J Ther Rehab 17(6): 310322.

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, et al. (1999) Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 281(7): 613-620.

- Newcomer R, Maravilla V, Faculjak P, Graves MT (2004) Outcomes of preventive case management among high-risk elderly in three medical groups: a randomized clinical trial. Eval Health Prof 27(4): 323-348.

- Bird SR, Kurowski W, Dickman GK, Kronborg I (2007) Integrated care facilitation for older patients with complex health care needs reduces hospital demand. Aust Health Rev 31(3): 451-461.

- Landi F, Onder G, Russo A, Tabaccanti S, Rollo R et al. (2001) A new model of integrated home care for the elderly: impact on hospital use. J Clin Epidemiol 54(9): 968-970.

- Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, Brooks D, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of early discharge planning in acutely ill or injured hospitalized older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 13:70.

- Himsworth RL, Goldacre MJ (1999) Does time spent in hospital in the final 15 years of life increase with age at death? A population based study. BMJ 319(7221): 1338-1339.

- Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE (2015) Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med 175(4): 559-565.

- Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, et al. (1992) Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 41(3): 237-248.