Perception of Physical Capacity and IADL Performance in Older Men

Kathye E Light* and Mary T Thigpen

Department of Physical Therapy, Brenau University

Submission: June 06, 2017; Published: August 24, 2017

*Corresponding author: Kathye E Light, Brenau University, 301 Main Street SW, Gainesville GA 30501, USA, Fax: 678-971-1834; Email: klight@brenau.edu

How to cite this article: Light KE, Thigpen MT. Perception of Physical Capacity and IADL Performance in Older Men. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2017; 2(2): 555583 DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2017.02.555583

Abstract

Background/Objective: What is the relationship of what we do and what we think we can do? The perception of illness has been linked to decreased activity participation, but what is the relationship of what we actually do during the day and our perception of physical limitations.In years past, men tended to build self-perception of capability more connected to work outside the home. Once retired, some older men lose this work definition and do not participate in household activities because of gender role perception of tasks. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship of physical limitation perception to the types of everyday activities performed at home.

Design: Correlation and Forward Step-wise Regression Analysis.

Setting: Geriatric Gait and Balance Clinic.

Participants: 120 older males (mean age = 78+ 8), referred by physicians to a Balance Clinic because of a history of falling (>2 in past year) and complaint of walking instability.

Intervention: None.

Measurements: MOS-36 and Frenchay IADLs.

Results: Five instrumental activities of daily living (Frenchay IADLs) had the strongest linear relationship with the physical capability perception (MOS-36). Those five were: Washing clothes, heavy housework, social outings, household/car maintenance, and walking outside >15 minutes.

Conclusion: These results indicate a strong relationship between perception of physical capacity and performing what has been considered traditionally female tasks, i.e., washing clothes, heavy housework, social outings as well as the more typical male tasks of household /car maintenance and the neutral gender task of walking outside.

Keywords: Successful aging; IADL; Physical capacity

Abbreviations: IADL: Instrumental Activities Of Daily Living; MOS: Medical Outcomes Study; PF: Physical Functioning; FAI: Frenchay Activity Index; SPSS: Statistical Package For The Social Sciences

Introduction

As individuals move into the last decades of their lives, declines in physical abilities are inevitable. The relationship of physical changes to an older person's function and self-efficacy levels is relevant to promoting successful aging. Particularly, selfefficacy has been associated with a buffering effect on functional decline of older adults with diminishing physical capacity levels [1]. Longitudinal studies also reveal that an older person's self-efficacy beliefs are related to decline in reported functional status [2]. Physical function in community-dwelling adults has been associated with several physical and psychosocial variables including general health, quality of life [3], activity levels and participation [4-5], pain, and depression [6]. In addition, one's perception of their physical abilities and actual physical fitness levels have been found to impact the performance of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) [7-8].

Our aim in this study was to examine perceptions in a cohort of elderly men referred to a Geriatric Gait and Balance Clinic. When considering successful aging unique to older men, the most frequent themes reported for successful aging were: good health; physical, mental, and social activity; functional independence; family and friends; and ability to make one's own decisions [9]. Studies of the relationships between older adults' physical abilities, functional levels, and perceptions of efficacy are only as valid as the measurement tools used. ADL and IADL measurement tools can include items that are considered gender-specific. When examining a cohort of men, items such as cooking, washing clothes, or vacuuming are traditionally considered housework performed by women and consequently may be considered invalid measures when examining the IADL performance level of a cohort of men.

Recent evidence examining gender roles in the household indicate that little has changed in the past thirty years in gender stereotypes in spite of women’s increased participation in the workforce, athletics, and professional education [10]. Milla n-Calenti [11] and colleagues also found IADL task self-efficacy differences between older Spanish men and women. Tasks related to money administration, medication schedules, and transportation favored men, while women scored higher in domestic activities such as laundry, housekeeping and cooking. Fuwa [12] argues that in spite of the fact that men are spending more time on household tasks, gender segregation of household tasks between couples persists with women continuing to perform the "core" household tasks while men’s tasks are more episodic or discretionary. In contrast, some older men do assume household responsibilities after retirement that they did not previously perform [13].

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships of physical capacity perception as measured by the PF SF-36 and the actual participation in home activities as measured by the Frenchay IADLs in a cohort of elderly men with balance and fall difficulty. Specifically, we are interested in the relationship between the physical capacity perception and the participation in the home environment of activities that have been traditionally classified as female tasks.

Methods

After IRB approval, a retrospective chart review was conducted on a consecutive sample of men who were referred to the Geriatric Gait and Balance Clinic. Patient criteria for referral to the clinic included: a complaint of gait instability, concern of falling by the patient, more than 2 falls in the past year, ability to follow instructions and a willingness to exercise to get better. Data were reviewed for 175 patients; however, due to missing values on the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form 36 (SF-36), or a request for nonparticipation in any research study, only 120 charts (69%) were included in the review. Primary diagnoses and co-morbidities varied greatly, as is typical of a frail elderly group seeking physical therapy for gait and balance intervention. Common diagnoses were osteoarthritis, Parkinson Disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, and previous hip fractures.

Instruments

Data from two outcome measures were analyzed, the physical functioning (PF) subsection of the SF-36 and the Frenchay Activity Index (FAI). Both are self-report measures obtained via interview. These data were collected by one of two evaluating physical therapists on the patient’s first visit prior to the initiation of a treatment regimen.

The PF subsection of the SF-36 is a reliable and valid 10-item scale that measures one's self-perception of physical functioning [14]. The subscale is scored from 0 to 30; higher scores are associated with better physical function perceptions. The FAI is a 15 item assessment initially developed to assess social and lifestyle activities beyond those required for personal care. The reliability and validity of the scale has since been established for many populations beyond stroke, including elderly populations [15]. A 4 item Like rt scale is used for each question, with 1 indicating no participation, and 4 indicating frequent participation. Higher scores indicate frequent participation in activities.

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Pearson correlation coefficients were used to identify the strength of the relationships between the PF SF-36 score and the individual FAI scores. Forward stepwise linear regression was calculated to identify which FAI items account for most of the variance of the PF SF-36 score.

Results

Descriptive

The score on the PF SF-36 ranges from 0 to 30 with 30 indicating high perception of physical health. The mean of PF SF-36 score is 16.8 with a standard deviation of 5.38, indicating relatively low perceptions of physical functional capability. The score on FAI ranges from 0 to 60, with 60 indicating high levels of activity. The mean FAI score was 31.6, with a standard deviation of 9.93, indicating that this sample was overall not very physically active.

Correlations

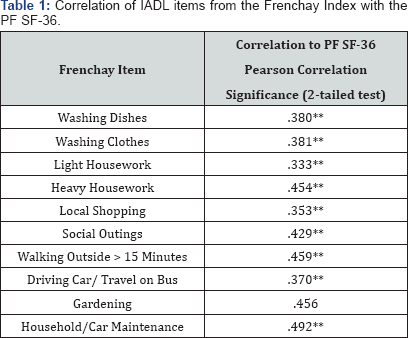

A Pearson correlation coefficient was used to calculate the relationship between each item on the FAI with the total PF SF-36 score. The ten FAI items that demonstrated significant correlation at .001 levels were: washing dishes, washing clothes, light housework, heavy housework, local shopping, and social outings, walking outside > 15 minutes, driving car/travel on bus, gardening, and household and/or car maintenance. The items which did not correlate were: preparing main meals, actively pursuing a hobby, travel outings/car rides, reading books, and gainful work. See Table 1.

**Significant at the 0.01 level

Model 1: Predictors: (Constant), F13 (household/car maintenance)

Model 2: Predictors: (Constant), F13, F5 (household/carmaintenance, heavyhouseworkrespectively)

Model 3: Predictors: (Constant), F13, F5, F8 (household/ carmaintenance, heavyhousework, walk outside>15 minutes respectively)

Model 4: Predictors: (Constant), F13, F5, F8, F7 (household/ car maintenance, heavy house work, walk outside>15minutes, socialoutingsrespectively)

Model 5: Predictors: (Constant), F13, F5, F8, F7, F3 (household/ car maintenance, heavy housework, walk outside>15minutes, social outings, washing clothes respectively)

The Best-fit model of factors accounting for the greatest variance was analyzed with forward step wise linear regression. This method identified the variables that account for the greatest variance in the PFSF- 36 score. The best-fit model included house hold maintenance, social outings, walking outside>15minutes, heavy house work and washing clothes; together these factors account for 49% of the variance in the PFSF-36 scores. See Table 2.

Discussion

What is the relationship of what we do and what we think we can do? In this study we examined the relationship between self-perceptions of physical capability and IADLs in older men. The regression model explained 49% of the variance in physical health perceptions cores by identifying that the ability to perform specific IADLs and social activities predict the reporting of physical capability. Strong linear relationships were found between perceptions of physical capability and the following items: washing clothes, heavy housework, social outings, walking outside > 15 minutes, household and/or car maintenance. Interestingly, the strongest correlations were primarily with traditional female tasks (washing clothes, heavy house work and social outings).

Many factors can be considered that could possibly contribute to these results. Coltrane [16] identified several predictors of how household labor will be divided as well as when men take on more or less of the housework. Education plays a definite role with more educated women doing less housework, and more educated men doing more [17]. Spouses with similar ideologies regarding equal division of the workload also see men performing more of the traditional female roles [18]. Some studies have shown that men increase their contributions to household labor after retirement, while others suggest that retirement does not change the gender division of labor significantly [19]. Marital satisfaction appears to play a role, with increased marital satisfaction leading to more shared household responsibilities [20].

When looking more closely at the specific items identified in this study, each plays a role in successful aging. Regardless of gender or age, housekeeping and laundry activities have been related to higher perceptions of health [21,22]. Walking >15 minutes outdoors has also been associated with higher perceptions of health and as an indicator of successful again [4]. Finally, levels and types of social support, such as the FAI item 'maintaining social outings' are positively related to perceptions of health and negatively linked to depression and perceptions of disability [23-24].

Limitations of this study include the use of only two measures. While these measures succinctly address the areas of interest, the addition of other psychosocial measures may increase the explanation of the results. Further, this was a cross- sectional sample which does not explain how the patient’s abilities and activity participation may change overtime. In that our purpose was specific to older men, these results can only apply to the male population. By examining the relationship between the perception of physical capability and daily, home-activity participation, we were able to identify specific activities which indicate better physical capability perceptions. There appears to be a benefit to older men to embrace responsibility within the home. Rehabilitation therapists can use this information to assist interventions directed at increasing functional participation of older males.

References

- De Leon CFM, Seeman TE, Baker DI, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME, et al. (1996) Self-efficacy, physical decline, and change in functioning in community-living elders: a prospective study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 51(4): S183-S190.

- Seeman TE, Unger JB, McAvay G (1999) Self-efficacy and perceived declines in functional ability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 54B(4): P214-P222.

- Gayman MD, Turner RJ, Cui M (2008) Physical limitations and depressive symptoms: exploring the nature of the association. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 63B(4): S219-S228.

- Garber CE, Greaney ML, Riebe D, Nigg CR, Burbank PA, et al. (2010) Physical and mental health-related correlates of physical function in community dwelling older adults: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr.

- Brach JS, Van Swearingen JM, FitzGerald SJ, Storti KL, Kriska AM, et al. (2004) The relationship among physical activity, obesity, and physical function in community-dwelling older women. Prev Med 39(1): 74-80.

- Rejeski WJ and Mihalko SL (2001) Physical activity and quality of life in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2: 23-35.

- Lin PS, Scieh CC, Tseng TJ, Su SC (2016) Association between physical fitness and successful aging in Taiwanese older adults. PLoS One 11(3): e0150389.

- Cho CY, Alessi CA, Cho M, et al. (1998) The association between chronic illness and functional change among participants in a comprehensive geriatric assessment program. J Am Geriatr Soc 46(6): 677-682.

- Tate RB, Lah L, Cuddy TE (2003) Definition of successful aging by elderly Canadian males: the Manitoba Follow-up Study. Gerontologist 43(5): 735-44.

- Haines EL, Deaux K, Lofaro N (2016) The times they are a-changing . . . or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983-2014. [Psychol Women Q 40(3): 353-363.

- Millan-Calenti JC, Tubi'o J, Pita-Fernandez S, et al. (2010) Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 50(3): 306-310.

- Fuwa M (2004) Macro-level gender inequality and the division of household labor in 22 countries. Am Socio Rev 69(6): 751-767.

- Szinovacz ME (2000) Changes in housework after retirement: a panel analysis. J Marriage Fam 62(1): 78-92.

- Ware JE (1976) Scales for measuring general health perceptions. Health Serv Res 11: 396-415.

- Turnbull JC, Kersten P, Habib M (2000) Validation of the Frenchay Activities Index in a general population aged 16 years and older. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81(8): 1034-1038.

- Coltrane S (2000) Research on household labor: modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. J Marriage Fam 62(4): 1208-1233.

- Orbuch TL, Eyster SL (1999) Division of household labor among black couples and white couples. Soc Forces 76: 301-332.

- Greenstein TN (1996) Gender ideology and perceptions of fairness of the division of household labor: effects on marital quality. Soc Forces 74: 1029-1042.

- Pina DL, Bengtson VL (1995) Division of household labor and the wellbeing of retirement-aged wives. Gerontologist 35: 308-317.

- Ward RA (1993) Marital happiness and household equity in later life. J Marriage Fam 55: 427-438.

- Gama EV, Damian JE, Perez de Molino J et al. (2000) Association of individual activities of daily living we self-rated health in older people. Age Ageing 29(3): 267-270.

- Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ et al. (1996) Successful aging: Predictors and associated activities. Am J Epidemiol 144: 135-141.

- Glass TA, de Leon CM, Marottoli RA, Berkman LF (1999) Population based study of social and productive activities as predictors of survival among elderly Americans. BMJ 319(7208): 478-83.

- Hardy SE, Concato J, Gill TM (2004) Resilience of community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(2): 257-262.