Amino Acids, Fatty Acids and Volatile Compounds of Yoghurt Supplemented with Probiotic, Royal Jelly and Pollen Grain

Atallah A*

Department of Dairy Science, Benha University, Egypt

Submission: March 20, 2018;Published: May 09, 2018

*Corresponding author: Atallah Abdel-Razek Atallah, Department of Dairy Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Benha University, Qaluobia, Egypt, Tel: +201225922632; Fax: +20132467786; Email: atallah.mabrouk@fagr.bu.edu.eg

How to cite this article: Atallah A. Amino Acids, Fatty Acids and Volatile Compounds of Yoghurt Supplemented with Probiotic, Royal Jelly and Pollen Grain. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2018; 6(4): 555692. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2018.06.555692.

Abstract

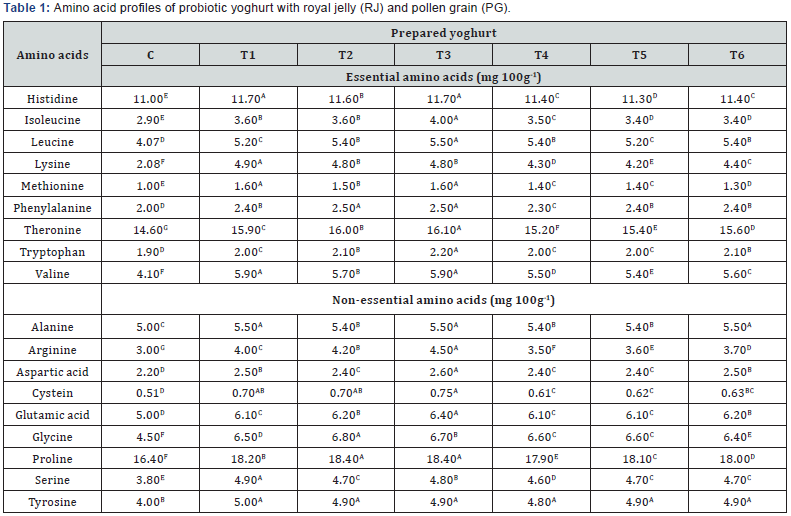

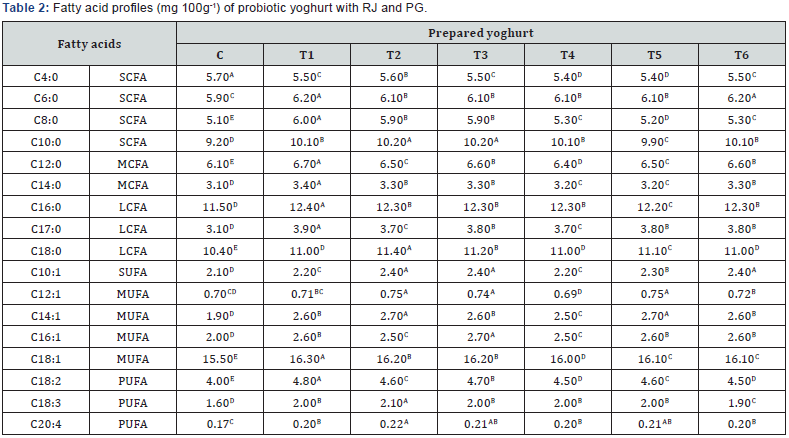

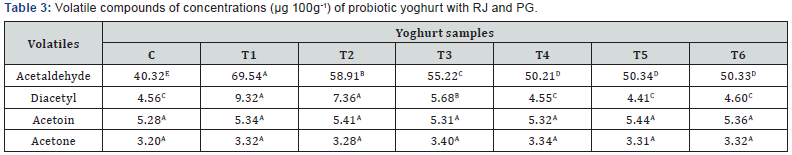

The effects of adding RJ and PG with probiotic strains (Bifidobacterium angulatum, Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus rhamnosus) on the AA; FA and volatile compounds of yoghurt were studied. Addition of RJ and PG increased significantly AA and FA contents of the prepared yoghurt. The yoghurt treatments (T1, T2,T3) were higher (P<0.05) in the content of histidine, isoleucine, lysine, methionine, theronine, valine, arginine, cysteine and proline. Also, the SCFA, MCFA, LCFA, USFA, MUFA and PUFA contents were significantly higher in T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 than in control sample, except C4:0, it was higher in the control sample. The highest concentrations of acetaldehyde (P<0.05) were obtained in T1 treatment (69.54μg 100g-1), while, the lowest concentrations of acetaldehyde (P<0.05) were recorded in control sample (40.32μg 100g-1).

Keywords: Yoghurt; Probiotic; Amino acids; Fatty acids; Volatile compounds; Minerals; Nutrition;

Abbreviations: Rj: Royal Ielly; Pg: Pollen Grain; Aa: Amino Acid; Fa: Fatty Acid; Scfa: Short-Chain Fatty Acids; Mcfa: Medium-Chain Fatty Acids; Lcfa: Long-Chain Fatty Acids; Usfa: Short-Unsaturated Fatty Acids; Mufa: Mono-Unsaturated Fatty Acids; Pufa: Poly-Unsaturated Fatty Acids

Practical Applications

Recently, yoghurt is a product that is consumed in large quantities and to increase the nutritional and functional value has been supported by the use of some additives, namely probiotics, pollen and royal jelly, because of the characteristic of these materials of therapeutic and functional value of high nutritional value. This work anticipated that would supplement yoghurt with common, healthful, agreeable and accessible honey bee products (RJ and PG) and probiotic; and to contemplate the impact of adding these materials on amino acids and fatty acids, volatile compounds and minerals of prepared yoghurt.

Introduction

Yoghurts are produced by milk fermentation with bacterial strains comprising of a blend of Str. thermophilus and Lb. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Probiotics are live microorganisms that offer preferences to the host when used in adequate amounts [1]. Most probiotics are microorganisms like those normally found in individuals' guts, particularly in breastfed infants who have characteristic protection against many diseases. The biggest group of probiotic strains in the intestine is lactic acid bacteria, of which Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. Probiotics are found to apply other health preferences for example enhancing lactose intolerance, increasing humoral immune responses, biotransformation of isoflavone phytoestrogen to enhance post-menopausal symptoms, bioconversion of bioactive peptides for antihypertension, and decreasing serum cholesterol level [2].

Pollens are the male gametophytes of flowers. Potential utilizations of pollen grain incorporate its utilization in apitherapy and as a functional food. Pollen grains contain of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, minerals, amino acids and vitamins (A, B, C, D, and E). The therapeutic activity has been ascribed to few phenolic components with antioxidant activity, display in these materials (Isla et al., 2001) [3].

Another important bee product is royal jelly. The utilization of RJ isn't limited to its high substance in respectable substances, yet in addition to its animating and functional values. Likewise, different kinds of RJ showed antimicrobial activity against sustenance borne pathogenic microorganisms [4]. The chief components of RJ are moisture (65%), protein (12%), carbohydrates (15%), lipids (5%), vitamins and mineral salts.

This work intended to supplement yoghurt with common, dietary, agreeable and accessible bee items (RJ and PG) and probiotic; and to contemplate the impact of including these materials on amino acids and fatty acids, volatile compounds and minerals of produced yoghurt.

Materials and Methods

Ingredients

Fresh cow and buffalo milks; PG and RJ were gotten from the apiary of the Faculty of Agriculture, Benha University, Egypt. The RJ was stuffed in misty plastic vials, and kept solidified until utilized.

Strains

Yoghurt cultures comprising of Lb. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Str. thermophilus (1:1) were gotten from Chr. Hansen's Laboratories, Copenhagen, Denmark. Probiotic strains including, Bifidobacterium angulatum DSM 20098, Lactobacillus gasseri ATCC 33323 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus DSM 20245 were gotten from Institute of Microbiology, Federal Research Center for Nutrition and Food, Kiel, Germany.

Manufacture of yoghurt

Fresh milk mixture (cow milk and buffalo milk, 1:1) was institutionalized to ~ 3% fat, heated to 85 °C for 30 min, instantly cooled to 42 °C and divided into seven parts as follows:

I. (C) Control inoculated with 3% yoghurt starter.

II. (T1) milk was supplemented with 0.6% RJ and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb.rhamnosus.

III. (T2) the same as T1, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus.

IV. (T3) the same as T1, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus.

V. (T4) milk was supplemented with 0.8% PG and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb.rhamnosus.

VI. (T5) the same as T4, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus.

VII. (T6) the same as T4, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus.

All samples were filled into plastic glasses (80ml) and incubated at 42 °C until the point when the pH came to ~4.6. The samples were cooled and put in a refrigerator at 4 ± 1 °C and investigated for its amino acids and fatty acids, volatile compounds and minerals.

Amino acids

The amino acid of yoghurt samples was resolved as portrayed by Spackman et al. [5] utilizing an amino acid analyzer (Technical TSM-1 model DWA 0209 Ireland). The samples were dried to consistent weight, defatted, hydrolyzed and evaporated in a rotary evaporator and in this manner set in a Technician Sequential Multisampling amino acid analyzer (TSM).

Fatty acids

The prepared yoghurt samples were taken for investigation of fatty acid substance. Extraction of the fat from the samples was performed utilizing the Rose-Gottlieb method. The fatty acid substance was resolved on a gas chromatograph “Pay- Unicom 304” with a flame-ionization detector and a capillary column ЕСТМ-WAX, 30m, ID 0,25mm, Film: 0,25μm. The extraction of fat was resolved utilizing the modified fatty acid methyl ester method as portrayed by Baydar et al. [6].

Volatile compounds (VC)

Volatile Compounds were resolved of the prepared yoghurt samples according to Güler [7]. VCs were examined utilizing an Agilent model 6890 gas chromatography (GC) and 5973 N mass selective detector (MS). Columns utilized for FFA separation HP-INNOWAX capillary column (30m ×0.32mm id ×0.25μm film thickness).The volatile compounds were isolated under the following conditions: injector temperature 200 °C; carrier gas helium at a flow rate of 1.4 ml min–1; oven temperature program initially held at 50 ˚C for 6 min and then programmed from 50 °C to 180 °C at 8 °C min–1 held at 180 °C for 5 min. The interface line to MS was set at 250 ˚C. Identification of the compounds was likewise directed by a computer matching. In view of the pinnacle determination, their zones were assessed from the combinations performed on selected ions. The resulting peak areas were communicated in the subjective area units. Evaluation of constituents was figured by outer standard method.

Minerals

Trace elements content had been estimated according to the method by James [8] in Analytical Chemistry of Foods. The dilutions were applied to the atomic absorption spectrophotometer to estimate the levels of investigated elements using atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AA- 630-02 Shimadzu-Japan).

Statistical analysis

The statistical examination was completed utilizing measurable program (MSTAT-C 1989) with multi-function utility in regards to the test plan under significance level of 0.05 for the entire outcomes. Different examinations applying LSD were completed by Snedecor & Cochran [9].

Results and Discussion

Amino acid profiles of produced yoghurt

The changes in levels of amino acid in yoghurt treatments were measured (Table 1). As can be seen from the table, all the yoghurt samples contained nine basic amino acids in particular histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, theronine, tryptophan and valine while the unimportant amino acids were alanine, arginine, aspartic acid, cystein, glutamic acid, glycine, proline, serine and tyrosine. In both probiotic yoghurt treatments with RJ (T1, T2, T3) and PG (T4, T5, T6), the total amino acids content was higher (P<0.05) contrasted with the C treatment. The probiotic yoghurt containing RJ (T1, T2, T3) were higher (P<0.05) in the histidine, isoleucine, lysine, methionine, theronine, valine, arginine, cysteine and proline contents. While, the control yoghurt was lower in the all amino acids.

C: Control inoculated with 3% yoghurt starter; T1: milk was supplemented with 0.6% RJ and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T2: the same as T1, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T3: the same as T1, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T4: milk was supplemented with 0.8% PG and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T5: the same as T4, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T6: the same as T4, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus A-G Different letters in the same row indicate significant statistical differences (Duncan's test P<0.05).

The three expanded chain amino acid isoleucine, leucine and valine support numerous metabolic procedures extending from the central part as substrates for protein synthesis to metabolic parts as energy substrates [10], antecedents for synthesis of alanine and glutamine and as modulators of muscle protein synthesis [11]. Sulfur amino acids and their metabolites are of major significance in health and infection. Methionine is named nutritiously fundamental. Cysteine is delegated semi fundamental because of the variable limit of body for its creation from methionine [12].

Methionine and cysteine substances were higher in T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 treatments contrasted with C sample, with the increase being the biggest (P<0.05) in the T1, T2 and T3, individually. Methionine varied from 1.00mg 100g-1 in C sample up to 1.6mg 100g-1 in T1 and T3 samples. The nonessential amino acids had increased (P<0.05) in the T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6, contrasted with C. T1, T2 and T3 samples demonstrated higher (P<0.05) content of arginine, cysteine and proline amino acids than those of yoghurt samples (T4, T5 and T6) or C (Table 1).

Proline, glutamic and aspartic acids, lysine and leucine are the transcendent amino acids, constituting roughly 55% of total amino acids in pollen grain [13].

Fatty acid profiles of produced yoghurt

Data on the FA contents of produced yoghurt are displayed in Table 2. A sum of 15 fatty acids were identified, involved both saturated (SFA) and unsaturated fatty acids (USFA). The level of oleic acid (C18:1) in produced yoghurt were the most elevated among every single fatty acids. In yoghurts, SFA was the predominant fatty acid and includes capric acid, C10:0; palmitic acid, C16:0 and stearic acid, C18:0.

C: Control inoculated with 3% yoghurt starter; T1: milk was supplemented with 0.6% RJ and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starters and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T2: the same as T1, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T3: the same as T1, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T4: milk was supplemented with 0.8% PG and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T5: the same as T4, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T6: the same as T4, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus SCFA=Short-chain fatty acids, MCFA= Medium-chain fatty acids, LCFA= Long-chain fatty acids, SUFA= Short-unsaturated fatty acids, MUFA= Medium- unsaturated fatty acids, PUFA= Poly- unsaturated fatty acids A-E Different letters in the same row indicate significant statistical differences (Duncan's test P<0.05)

The proportion of LCFA in produced yoghurts was the highest, followed MUFA, MCFA and PUFA. The proportion of different groups of fatty acids in T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 samples were consistently higher (P<0.05) than that in C, except C4:0 it was higher in the C sample. The principal LCFA in all yoghurt was palmitic acid (C16:0), MCFA was lauric acid (C12:0), and SCFA was capric acid (C10:0), and MUFA was oleic acid (C18:1), and PUFA was linoleic acid (C18:2). The fatty acids of T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 treatments were high in USFA.

This finding is like other investigated conventional Greek yogurt, that the dominating SFA in the sample were myristic acid (C14:0), palmitic acid (C16:0), and stearic acid (C18:0), while the predominant MUFA was oleic acid (C18:1) [14]. Unsaturated fatty acids assume an imperative part in human nutrition and health, adds to cholesterol lowering and thus coronary illness chance diminishment by increasing the high density lipoprotein (HDL) in blood [15].

The contents of most vital fatty acids -C18:1, C18:2, C18:3 and C20:4- were significantly (P<0.05) higher in T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 than in C. The SCFA contents (from C4:0 to C10:0) in T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 were higher (P<0.05) when contrasted with C sample (Table 2). The content of C4:0 in C sample was higher (P<0.05) contrasted with different treatments. The amount of MCFA (from C12:0 to C14:0) decreased (P<0.05) in C, contrasted with different treatments. Yet, the amount of MCFA and LCFA increased (P<0.05) in T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6, contrasted with C.

Szczesna & Rybak-Chmielewska [13] demonstrated that, the lipids of Honey bee dust in the concentrate comprise for the most part of: linolenic, palmitic, linoleic and oleic acids from GC investigation. Unsaturated fats constitute all things considered around 70% of the aggregate.

Volatile compounds profiles of produced yoghurt

The volatile compounds found in yogurt samples are showed in Table 3. There were significant differences (P<0.05) in acetaldehyde concentration of prepared yoghurts. The highest concentrations of acetaldehyde (P<0.05) were obtained in T1 treatment (69.54μg 100g-1), while, the lowest concentrations of acetaldehyde (P<0.05) were recorded in C treatment (40.32μg 100g-1). Ketones are normal constituents of produced yoghurt as other volatile compounds. Despite the fact that diketone diacetyl (2, 3 butanedione) was varied (P<0.05), it was distinguished in yoghurt treatments. The maximum content of diacetyl was recorded in T1 treatment followed by T2 and T3 treatments. The other volatile compound such as ethanol was not detected in all yoghurt samples.

C: Control inoculated with 3% yoghurt starter; T1: milk was supplemented with 0.6% RJ and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T2: the same as T1, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T3: the same as T1, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T4: milk was supplemented with 0.8% PG and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T5: the same as T4, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T6: the same as T4, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. Rhamnosus A-E Different letters in the same row indicate significant statistical differences (Duncan's test P<0.05)

Monnet & Corrieu [15] demonstrated that dike tones in yoghurt come just from pyruvate, since thermophilic starter cultures can process citrate. There were non-significant differences (P>0.05) in acetoin and acetone concentration in yoghurt samples. This methyl ketone is gotten from β-oxidation of saturated free fatty acids relying upon the lipolytic action of yoghurt bacteria [16]. Stelios et al. [17] found that these ketones expanded in yoghurts relying upon the increase in content of fat and storage period.

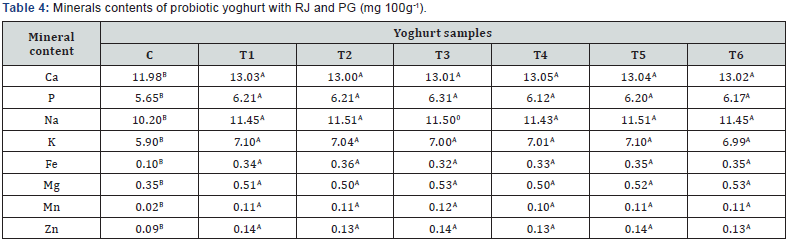

Minerals content of produced yoghurt

The impact of RJ, PG and probiotic bacteria on the mineral of prepared yoghurt samples is shown in Table 4. Expansion of RJ treatments (T1, T2 and T3) and PG treatments (T4, T5 and T6) to yoghurt prompts an increase in its minerals content (P<0.05). Calcium was high concentration (between 11.98 to 13.11mg 100g-1), while Mn was low concentration f (between 0.02 to 0.11 mg 100g-1) of yoghurt samples.

C: Control inoculated with 3% yoghurt starter; T1: milk was supplemented with 0.6% RJ and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T2: the same as T1, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T3: the same as T1, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T4: milk was supplemented with 0.8% PG and inoculated with 1.5% yoghurt starter and 1.5% Lb. rhamnosus; T5: the same as T4, but with the use of Lb. gasseri lustead of Lb. rhamnosus; T6: the same as T4, but with the use of Bif. angulatum lustead of Lb. Rhamnosus A-B Different letters in the same row indicate significant statistical differences (Duncan's test P<0.05)

These results agree with those reported by Stocker et al. [18], who identified different trace and mineral components in royal jelly that could be ascribed to an outside factor, for example, environment; different botanical and geological origins and to some degree inside variables, for example, biological factors related to the bees [19].

Conclusion

Yoghurt made using probiotic, RJ and PG with a decent nutritional quality. The AA and FA contents were significantly different (P<0.05) between the yoghurt T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 than in C sample. Addition of RJ and PG increased significantly AA and FA contents of the prepared yoghurt. Also, the SCFA, MCFA, LCFA, SUFA, MUFA and PUFA contents were significantly higher in the yoghurts (T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6) than in C sample, except C4:0, it was higher in C sample. Calcium was the high concentration element, while, Mn was the low concentration of produced yoghurt treatments. Finally the treatments contain RJ, PG and probiotic was chosen as the most attractive treatments as far as AA and FA, and was suggested for the preparation of high quality yoghurt, it's supplemented with characteristic, dietary, acceptable and accessible honey bee products and probiotic strains.

Significance Statements

The yoghurt made using probiotic, RJ and PG with a decent dietary quality. The AA and FA contents were significantly different (P<0.05) between the yoghurt containing RJ (T1, T2, T3) and PG (T4, T5, T6) than in C sample. Addition of RJ and PG increased significantly AA and FA contents of the prepared yoghurt.

The yogurt made utilizing probiotic, RJ and PG with a decent dietary quality. The AA and FA substance were essentially extraordinary (P<0.05) between the yogurt containing RJ (T1, T2, T3) and PG (T4, T5, T6) than in C test. Expansion of RJ and PG expanded essentially AA and FA substance of the readied yogurt.

References

- Lourens-Hattingh A, Viljoen BC (2001) Review: Yogurt as a probiotic carrier. Int Dairy J 11: 1-17.

- Liong MT (2007) Probiotics: a critical review of their potential role as antihypertensives, immune modulators, hypocholesterolemics, and perimenopausal treatments. Nutr Rev 65(7): 316-328.

- Isla MI, Moreno MIN, Sampietro AR, Vattuone MA (2001) Antioxidant activity of Argrntine propolis extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol 76(2): 165- 170.

- Attalla KM, Owayss AA, Mohanny KM (2007) Antibacterial activities of bee venom, propolis and royal jelly produce by three honey bee, Apis mellifera L hybrids reared in the same environmental conditions. Annals of Agric Sci Moshtohor 45(2): 895-902.

- Spackman MR, Stein WH, Moore S (1958) Automatic recording apparatus for use in the chromatography of amino acids. Anal Chem 30(7): 1190-1206.

- Baydar H, Marquard R, Turgut I (1999) Pure line selection for improved yield, oil content and different fatty acid composition of sesame, Sesamum indicum. Plant Breeding 118(5): 462-464.

- Güler Z (2007) Changes in salted yoghurt during storage. Int J Food Sci and Techn 42(2): 235-245.

- James CS (1995) Analytical Chemistry of Foods. Blackie Academic & Professional, London, UK.

- Snedecor GA, Cochran WG (1994) Statistical method. Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames, USA.

- Harper AE, Miller RH, Block KP (1984) Branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Ann Rev Nutr 4: 409-454.

- Anthony JC, Anthony TG, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS (2001) Signaling pathways involved in translational control of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle by leucine. J Nutr 131(3): 856S-860S.

- Grimble RF (2006) The effects of sulfur amino acid intake on immune function in humans. J Nutr. 136(6 Suppl): 1660S-1665S.

- Szczesna T, Rybak-Chmielewska H (1998) Some properties of honey bee collected pollen in Polnisch-Deutsches Symposium Salus Apis Mellifera, new demands for honey bee breeding in the 21st century. Pszczelnicze Zeszyty Naukowe 42(2): 79-80.

- Serafeimidou A, Zlatanos S, Laskaridis K, Sagredos A (2012) Chemical characteristics, fatty acid composition and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) content of traditional Greek yogurts. Food Chem 134(4): 1839- 1846.

- Monnet C, Corrieu G (2007) Selection and properties of alphaacetolactate decarboxylase-deficient spontaneous mutants of Streptococcus thermophilus. Food Microbiol 24(6): 601-606.

- Tsau JL, Guffanti AA, Montville TJ (1992) Conversion of pyruvate to acetoin helps to maintain pH homeostasis in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 58(3): 891-894.

- Stelios K, Stamou P, Massouras T (2007) Comparison of the characteristics of set type yoghurt made from ovine milk of different fat content. Int J Food Sci and Technol 42(9): 1019-1028.

- Stocker A, Schramel P, Kettrup A, Bengsch E (2005) Trace and mineral elements in royal jelly and homeostatic effects. J Trace Elem Med Biol 19(2-3): 183-189.

- Garcia-Amoedo LH, De Almaida-Muradian LB (2007) Physicochemical composition of pure and adulterated royal jelly. Química Nova 30(2): 257-259.