Awareness and Practices on Diet, Weight Management and Antenatal Care among Rural Pregnant Women

Protiva Rani Sarker1 and Md Monoarul Haque2,1*

District Manager, Health, Nutrition and Population Programme, CFPR-EHC, Bangladesh

Director, Research and Information, BSA, Bangladesh

Submission: September 27, 2015; Published:October 06, 2015

*Corresponding author: Md Monoarul Haque, Director, Research and Information, BSA, Bangladesh; Email: monoarmunna@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Sarker PR, Monoarul Haque MD. Awareness and Practices on Diet, Weight Management and Antenatal Care among Rural Pregnant Women. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2015;1(1): 555551. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2015.01.555551

Abstract

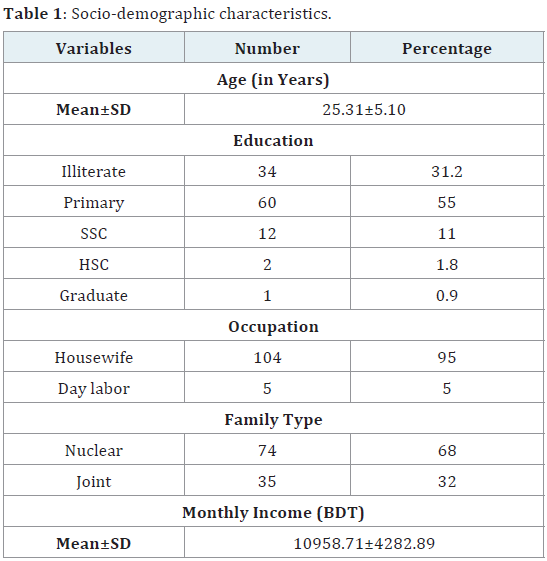

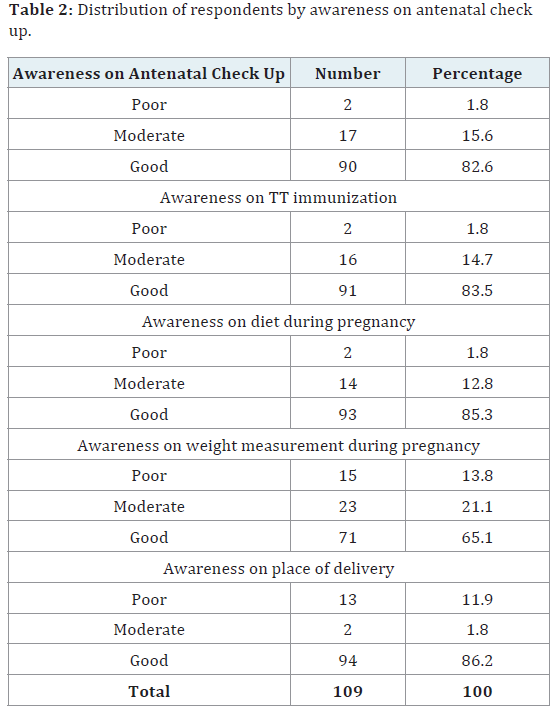

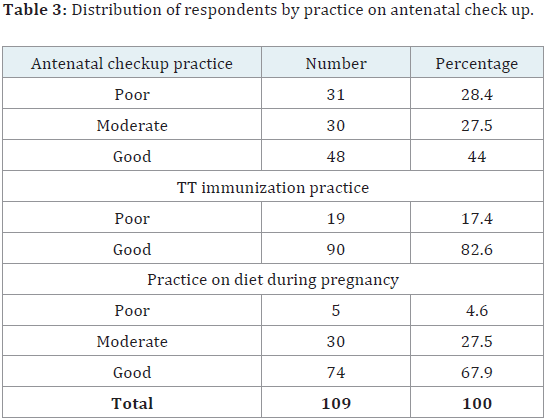

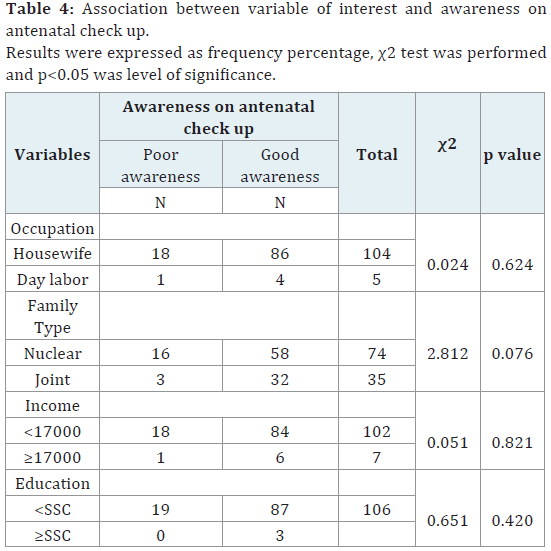

Neonatal morbidity and mortality remains very high in the developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America. An observational cross-sectional study was carried out at Sirajgonj district in Bangladesh to assess awareness and practice among rural pregnant women on diet, weight management as well as antenatal care. Face to face interview was carried out with structured questionnaire. Convenient sampling technique was used to collect data on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and written consent was taken prior to interview. Descriptive as well as inferential statistics were used to present data. Mean±SD age of respondents was 25.31±5.10 years. More than half (55%) of the respondents completed primary level education. Most of the respondents were housewife. Mean±SD income of respondents was 10958.71±4282.89 BDT. Distribution of nuclear and joint family were 68% and 32%. Most of the respondents (82.6%) had good awareness on antenatal checkup. Good awareness on TT immunization, diet during pregnancy, weight management and place of delivery was observed among respondents but half of the respondents practiced it. No statistical significant association was found between occupation, family type, education, income and awareness on antenatal checkup. It is concluded from the study that overall awareness level on different arena of diet and antenatal care among respondents was quite acceptable but in terms of practice it was unsatisfactory.

Keywords: Awareness; Practice; Antenatal Check Up

Abbreviations: WHO: World Health Organization; ANC: Antenatal Care; TT: Tetanus Toxoid

Introduction

Appropriate antenatal care is one of the pillars of Safe Motherhood Initiatives, a worldwide effort launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other collaborating agencies in 1987 aimed to reduce the number of deaths associated with pregnancy and childbirth (World Bank, 2007). It highlights the care of antenatal mothers as an important element in maternal healthcare as appropriate care will lead to successful pregnancy outcome and healthy babies. All pregnant ladies are recommended to go for their first antenatal check-up in the first trimester to identify and manage any medical complication as well as to screen them for any risk factors that may affect the progress and outcome of their pregnancy. Health knowledge is a vital element to enable women to be aware of their health status and the importance of appropriate antenatal care. Developing countries account for about 99% of an estimated half a million maternal deaths that occur each year [1]. A review of the Millennium Development Goals suggests that limited progress is being made to reduce maternal mortality especially across developing countries [2,3]. Ample evidence indicates that when women have greater knowledge through education, there is greater likelihood that they will have better pregnancy and delivery outcomes [4,5]. This is likely because acquiring knowledge through education equips women to make appropriate decisions about their health including during pregnancy and childbirth. A better informed woman is more likely to make appropriate decisions during obstetric emergencies [6], but many developing countries have women with poor education which is more prevalent in rural communities [7]. Proper ANC is one of the important ways in reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, many women in developing countries do not receive such care. Understanding maternal knowledge and practices of the community regarding care during pregnancy and delivery are required for program implementation. This study was conducted to determine awareness and practice related to antenatal care among these under privileged women in selected area in Sirajgonj District which can be used for further planning of health intervention programme.

Methodology

This was an observational cross-sectional study. This study was designed to grab more data in a short time, so that it can be used for assessing awareness and practice among the rural pregnant women and their practices on diet, weight management and antenatal care. Data were collected from Sirajgonj district. This study was conducted for a period of six month started from December 2014 to May 2015. Study was conducted among the rural pregnant women residing in selected area of Sirajgonj district. All pregnant women and willing to participate and also signed the informed consent were included. Convenient sampling method was used to select the sample. Data were collected from the respondents through face-to-face interview. First of all socioeconomic information was gathered. Then various questions were asked on antenatal care to see awareness level of respondents. At last I tried to know their practice level on antenatal care. The questionnaire was used after verbal consent of the respondents and their voluntary participation was sought. The bangle questionnaire was used during interview. Unstructured questionnaire was used to collect data. After data collection, data were sent to the researcher, which was sorted, scrutinized by the researcher herself by the selection criteria and then data were analyzed by personal computer by SPSS version 12.0 program. The open ended questions were grouped and categorized. Data were analyzed by descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The result of the study was presented in tabular and graphical form there by interpretation of the result in the chapter under the following headings. Three categories were defined on the basis of the score obtained by each participant: poor (<50% of the total score); moderate (50%-70% of the total score) and good (>70% of the total score) and it was pre-defined awareness scoring.

Results

Mean±SD of the respondents was 25.31±5.10 years. More than half of the respondents completed primary education. Almost all of them were housewife. More than two third respondents lived in nuclear family. Mean±SD income was 10958.71±4282.89 BDT (Table 1). Most of the respondents (82.6%) had good awareness on antenatal checkup. As like antenatal checkup awareness on TT vaccination was also good among 83.5% respondents. Regarding awareness on diet during pregnancy 85.3% of respondents showed good awareness. Good, moderate and poor awareness on weight management during pregnancy among respondents were 65.1%, 21.1% and 13.8%. About 86.2 and 11.9% respondents had awareness on place of delivery (Table 2). About 44%, 27.5% and 28.4% respondents practiced antenatal checkup. About 82.6% respondents took TT vaccine. Nearly two-third of respondents (67.9%) practiced diet during pregnancy (Table 3). No statistical significant association was found between occupation, family type, education, income and awareness on antenatal checkup (Table 4).

Discussion

Women usually considered pregnancy as a normal event unless complications arose, and most of them refrained from seeking antenatal care (ANC) except for confirmation of pregnancy, and no prior preparation for childbirth was taken. Financial constraints, coupled with traditional beliefs and rituals, delayed care-seeking in cases where complications arose. Delivery usually took place on the floor in the squatting posture and the attendants did not always follow antiseptic measures such as washing hands before conducting delivery. Following the birth of the baby, attention was mainly focused on the expulsion of the placenta and various maneuvres were adapted to hasten the process, which were sometimes harmful. There were multiple food-related taboos and restrictions, which decreased the consumption of protein during pregnancy and post-partum period. Women usually failed to go to the healthcare providers for illnesses in the post-partum period [8]. The present study found that most of the respondents (82.6%) had good awareness on antenatal checkup. Good awareness on TT vaccination, diet during pregnancy, weight management and place of delivery was observed among respondents but half of the respondents practiced it. No statistical significant association was found between occupation, family type and awareness on antenatal checkup. It may be due to numerous NGOs were working there regarding this issue. Antenatal care is one of the “four pillars” of safe motherhood, as formulated by the Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme, Division of Family Health of the World Health Organization [9]. Literature suggests that home visits by community-based health workers can help to reduce neonatal mortality by ensuring identification of pregnant women, and by ensuring optimal maternal health through both antenatal and postnatal care visits to their homes [10]. In South Asia and even in some of the African countries, only a small proportion of women perform deliveries in healthcare facilities [11]. Birth preparedness in this region is also low. Financial constraints coupled with traditional beliefs and rituals have been seen to delay and sometimes stop them altogether from taking any prior preparation for childbirth. This clearly means that there is a dire need to ensure a high level of awareness among pregnant women to address the importance of planned delivery. Beliefs and rituals also have an effect on maternal nutrition. The ultra poor households’ per capita mean food consumption is low compared to national average intake. Half of the ultra poor women are suffering from malnutrition [12], which often becomes worse because of food taboos during pregnancy and post-partum period. Pattern of prenatal and postnatal care indicate that 46% respondents did not take any antenatal cheek up during pregnancy. Iron tablet and T.T dose also avoided for different false thinking. The consciousness level of the pregnant women was also very low. They were affected different kind of postnatal complications. Most of the respondents possessed ill health. 38% respondents took help from untrained T.B.A and 32% respondent took help from relative to delivery. 64 per cent respondents did not get any service from N.G.O. Only 16% respondents got assists from the doctor during delivery. From the all findings, it is clear that economic and social causes are influential in this respect. A study was done in Abu Dhabi and they showed that 79.1% mother had heard of folic acid and 46.6% had accurate knowledge about the role of folate in preventing neural tube defects. There were good practices regarding folate supplementation in the current pregnancy; most of the interviewed mothers took it daily and in the recommended dose. However, only a minority took it prior to pregnancy. Education, irrespective of age or parity, was the major factor determining better knowledge of folic acid in pregnancy [13]. Another study revealed that 44.2% (95% CI, 34.7 – 53.7%) of the women have good knowledge regarding antenatal care while 53.8% (95% CI, 44.3 – 63.1%) of them noted to have positive attitude regarding antenatal care. However, result showed that the level of knowledge regarding the importance of early antenatal care, screening test and complications of diabetes and hypertension in pregnancy were poor [14].

Conclusion

It is concluded from the study that overall awareness level on different arena of antenatal care like TT vaccination, diet during pregnancy, weight management, place of delivery among respondents was quite acceptable but in terms of practice it was observed that they were well behind and not satisfactory. Association between occupation, family type and awareness on antenatal care found not significant.

References

- Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M, Ahn SY, Wang M, et al. (2010) Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millenium Development Goal 5. Lancet 375: 1609–1623.

- World Health Organization (2007) Maternal Mortality in 2005: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, p: 1-40.

- UNICEF (2008) Tracking progress in maternal, newborn & child survival. The 2008 Report.

- Harrison KA (1985) Childbearing, health and social priorities: a survey of 22,774 consecutive births in Zaria, Northern Nigeria. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 92(suppl 5): 1–119.

- Harrison KA (1997) The importance of the educated healthy woman in Africa. Lancet 349: 644-647.

- Jammeh A, Sundby J, Vangen S (2011) Barriers to emergency obstetric care services in perinatal deaths in rural gambia: a qualitative indepth interview study. ISRN Obstet Gynecol 2011: 981096.

- Sharma M, Sharma S (2012) Knowledge, attitude and belief of pregnant women towards safe motherhood in a rural Indian setting. Social Sciences Directory 1(1): 13.

- Choudhury N, Ahmed SM (2011) Maternal care practices among the ultra poor households in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative exploratory study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 11: 15.

- WHO (1994) Mother-Baby Package: Implementing safe motherhood in countries. Practical Guide: Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme Division, Geneva, Switzerland.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training and Save the Children-USA (2003) Newborn care practices in rural Bangladesh Dhaka.

- Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007.

- BRAC (2006) Towards a profile of the ultra poor in Bangladesh: Findings from CFPR/TUP baseline survey Dhaka.

- Al-Hossani H, Abouzeid H, Salah MM, Farag HM, Fawzy E (2010) Knowledge and practices of pregnant women about folic acid in pregnancy in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J 16(4): 402-407.

- Rosliza AM, Muhamad JJ (2011) Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Antenatal Care among Orang Asli Women in Jempol, Negeri Sembilan. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 11(2): 13-21.