How Does the Multi-Disciplinary Team Impact Chronic Kidney Disease Management?

Michael Fawzy1* and Baoying Huang2

1Faculty of urology, Renal consultant at Basildon University hospital, England

2Department of urology, Basildon University hospital, England

Submission: June 06, 2019; Published: July 11, 2019

*Corresponding author:Michael Fawzy, Faculty of urology, Renal consultant at Basildon University hospital, England

How to cite this article:Michael Fawzy, Baoying Huang. How Does the Multi-Disciplinary Team Impact Chronic Kidney Disease Management?. JOJ uro & nephron. 2019; 6(5): 555697. DOI : 10.19080/JOJUN.2019.06.555697

Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a condition where a gradual kidney function loss leads to a build-up of toxic waste products in the blood, increasing morbidity and premature deaths from enhanced risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke and mineral bone diseases. The most common causes of CKD include type II diabetes and hypertension, both accounting for two-thirds of all cases. CKD is asymptomatic in early stages and is only diagnosed via routine screening tests unless severe symptoms arise from advanced CKD. Management of CKD via multidisciplinary team (MDT) consisting of professionals from various disciplines has been hailed as the best modality in treating such a multi-faceted chronic disease, leading to positive impacts on patients’ experience and clinical outcomes.

Introduction

More than 1.8 million people are diagnosed with CKD in England [1] where the advancing age is commonly associated with the higher incidence of CKD stage 3-5. Figure 1 is an illustration that on average, whilst there is only an estimation of 1.9% of the population having moderate to severe CKD, that figure is increased to 32.7% for those aged 75 and over. The latest guideline established that NHS England spent £1.45 billion in 2009-10 attributing to £1 in every £77 spent by NHS in managing CKD and associated illnesses stemmed from the condition [1]. Progression patterns and risk factors of CKD into end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) can be established well before the need to initiate renal replacement therapy (RRT). Therefore, proactive intervention strategies to prevent its progression form a basis of management of CKD which is mainly delivered via a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) to address all the various aspects and risk factors of CKD. This paper aims to explore and describe how effective this MDT approach is in treating CKD.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

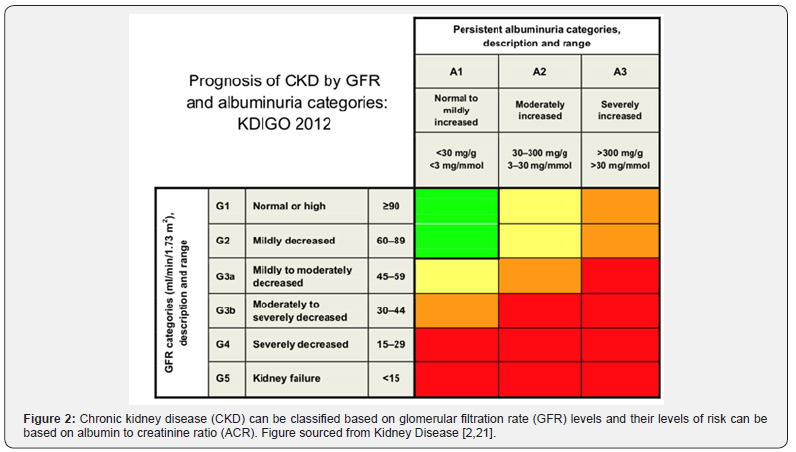

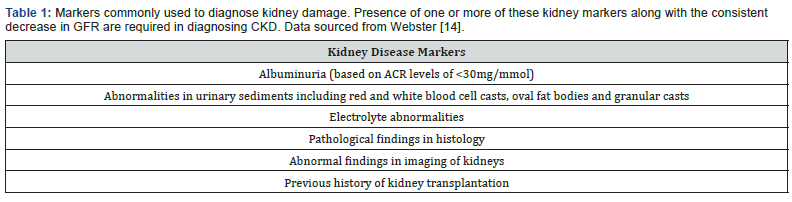

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a multi-factorial disease leading to progressive worsening of kidney functions. Kidney biopsies from most CKD patients will often show glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Moreover, at the end stage of kidney failure, they will feature a characteristic renal fibrosis where the kidney undergoes unsuccessful wound healing after chronic and sustained inflammation and injury to its tissues. CKD can be classified into 5 stages based on an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) which represents the amount of fluid each functioning unit (nephron) of kidneys filters through, per unit time. Figure 2 demonstrates the progression of CKD in stages using eGFR and albumin to creatinine (ACR) ratios [2]. A consistently high level of kidney disease markers (illustrated in Table 1) over a period of 3 months and a GFR at G3 stage are two criteria that need to be met in diagnosing CKD. G5 of GFR is termed as end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) where failure of kidney can only be managed with renal replacement therapy (RRT) including dialysis or kidney transplant unless the patient wishes to undergo conservative management.

Causes and Prevalence of CKD

Exact aetiology of CKD is not fully understood; however, older age, type II diabetes, and hypertension are associated with diabetic glomerulosclerosis and hypertensive nephrosclerosis both leading to CKD in Western world [3]. Main causes of CKD in developing countries include glomerular and tubulointerstitial diseases due to infections, drug and toxin exposure. A small percentage of CKDs also arises from congenital conditions such as polycystic kidney disease. Gender difference plays a role in CKD with males showing a more rapid and aggressive CKD progression, suggesting the potential roles of sex hormones in modulating synthesis of growth factors and chemical mediators leading to CKD progression [4]. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status are also key modifiers in CKD prevalence and progression. There is a 60% increased risk of worsening CKD in people of the lowest social quartile when compared with their richer counterparts. This progression is highest in people with ethnic minority backgrounds and can be attributed to having reduced medical awareness and access to specialist nephrologist care in both pre-dialysis and dialysis groups [5].

Clinical Presentation and Complications of CKD

CKD is non-symptomatic in the earlier stages and most diagnoses are made via routine tests unless patients present with severe symptoms from advanced CKD. As the kidney gradually loses its function from progressive disease, there is a rapid accumulation of uraemic retention solutes in the body which can then affect various parts of the body. Uraemic toxicity can lead to vascular damage increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases and bleeding episodes, impaired inflammatory and immune responses, and altered microflora in the digestive system [6]. Impairment to normal kidney functions can lead to proteinuria, oedema, hypertension, hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalaemia, anaemia and bleeding diathesis, renal osteodystrophy, congestive heart failure, gastrointestinal disturbances and generalised myopathy [7].

Multi-Disciplinary Team in Management of CKD

With medication compliance and adequate lifestyle changes including keeping a normal weight, taking up exercise and following a renal diet, CKD patients can remain as healthy as possible. Management plan is aimed to treat primary pathological diagnosis along with an intervention based on eGFR stages and albuminuria to control hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and anaemia to prevent episodes of acute kidney injury (AKI) and reduce its complications. A referral to nephrology is to be initiated when patients with poorly controlled hypertension even after treatment with at least 4 anti-hypertensive drugs, reach either G4 or G5 stage with decreasing GFR of less than 30ml/min/1.73m2 and an ACR of 10mg/mmol or higher [8].

A typical renal department provides inpatient and outpatient services covering general nephrology, pre- and post-dialysis review, low clearance clinics and transplant follow-up. The department is made up of a team of professionals from various disciplines including consultant nephrologists, clinical nurse specialists (CNS) and dieticians. Joint clinics are typically run in parallel with endocrinologists for diabetic patients with CKD, with cardiologists to manage their cardiovascular health and lastly with rheumatologists for patients with hyperuricemia to manage their gout and joint pain associated with CKD.

In addition, a team of MDT managing CKD also includes surgeons working together with interventional radiologists to get an intravenous line in or to form fistulae for good vascular access for dialysis. Interventional radiologists are valuable for the team since they can also perform other key procedures such as image-guided percutaneous renal biopsy allowing the clinicians to treat the underlying causes. In addition, the maintenance of fistulae and veins which allows good vascular access for future dialysis is relied upon the great effort of vascular access CNS who work alongside surgeons and radiologists to support the patients regarding fistulae care.

Role of MDT in Management of CKD

Anti-Hypertensive Therapy

There is a 57% increased mortality from cardiovascular causes when patients reach a GFR of less than 60mL/min per 1.73m2 [9]. In addition, CKD patients have 5-10-fold increased risks of dying from other complications than progress into ESKD [10]. Keith [11], also published results from a longitudinal study which concluded that CKD patients are twice likely to die from CVD complications than develop ESKD. Therefore, one of the roles of the consultant nephrologist is to prescribe anti-hypertensives accordingly, and to monitor patients’ blood pressure and other side effects arising from these therapies. Antagonists of reninangiotensin- aldosterone system such as angiotensin convertingenzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are first-line choice of agents in CKD patients to reduce proteinuria which is the main culprit for disease progression [12]. However, ARBs and ACEIs can also lead to hyperkalaemia in CKD patients and therefore should be continuously monitored for their blood potassium levels.

Management of Anaemia

One of the main functions of kidney is to produce erythropoietin (EPO) which is a hormone stimulating red blood cell production. CKD patients typically present with hypo proliferative, normocytic, and normochromic anaemia due to impaired EPO production by the kidneys. CKD patients often have chronic anaemia which reduces patients’ quality of life and puts them at higher risks of deaths. There is a 29% increased chance of hospitalisation in patients with haemoglobin (Hb) of <10 g/dl than those with Hb between 11-12 g/dl [13]. Therefore, iron and derivatives of recombinant erythropoietin are commonly used in treatment of anaemia, decreasing the need to transfuse blood [14]. Chronic anaemia is normally managed by anaemia CNS who monitor patients’ iron levels and administer intravenous iron and erythrocyte-stimulating agents (ESAs) to the patients, as prescribed by the nephrologists. They are also important in providing counselling sessions for pre-dialysis and dialysis patients informing them of local and national treatment guidelines to help decide their future treatment plan.

Management of CKD Mineral Bone Disease and Gout

The kidneys regulate how calcium and phosphate are absorbed in the intestine by regulating vitamin-D metabolism which converts vitamin-D to calcitriol (activated vitamin D). CKD patients can have abnormal serum concentrations of calcium, phosphates and reduced calcitriol levels, leading to pain in the bone or bone fragility due to increased osteoclast activity. Management of CKD mineral bone diseases include renal diets restricting phosphates and prescription of calcium or non-calcium phosphate-binders and activated vitamin D in those with low serum calcitriol levels (>30 ng/mL) and normal parathyroid hormone levels [2]. In addition, CKD patients often have high uric acid level (hyperuricemia) which can lead to acute or chronic gout attacks for which uric acid lowering agents such as allopurinol and febuxostat are used to manage hyperuricemia. Therefore, it is the role of the renal dieticians to offer guidance on which food to avoid and how to prepare an adequate meal for good renal health, along with offering support and help to lose weight, exercise more and quit smoking, if need be.

Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT)

There is no universal definition or endpoint of CKD at which ESKD can be diagnosed and renal replacement therapy (RRT) is to be established since patients can have differing levels of comorbidities. When the patients’ eGFRs start to approach 15%, they are consulted to discuss and make timely arrangement for further treatment plans including starting dialysis (either peritoneal or haemodialysis), kidney transplant or undertaking conservative treatment. However, a study supported by USA National Kidney Foundation concluded that an acceptable surrogate endpoint should be when a decrease of eGFR of 30- 40% within 2-3 years excluding causes of acute kidney injury (AKI) [15]. Generally, GFR of less than 15mL/min/1.73m2 along with presentation of uraemic symptoms can warrant a consultation of RRT which involves either dialysis or kidney transplantation.

RRT takes up a huge portion of NHS kidney budget and there was an estimated total annual cost for both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis of £505 million and a total annual cost for all transplants was reported to be £225 million in 2009-2010 [1]. Having a strong MDT team behind the patients makes an important difference to ESKD patients regarding making lifechanging decisions when considering RRT. There is a huge burden for patients to consider whether to enlist for RRT or undergo conservative management. A randomised control study carried out by Cooper et. al., in Australia and New Zealand in 2010 (IDEAL study) did not find any difference or improvement in survival outcomes and mortality rates when stage V CKD patients were started on early or late dialytic treatments. Therefore, it is paramount that a patient needs to be educated and consulted on optimal timing of initiating dialysis, which modality of dialysis to choose, extent of time waiting for the matched donor kidney for transplantation and how to cope with immunosuppressants and post-transplant complications.

Overall Impact of MDT in CKD

Incorporation of MDT in CKD care has been supported widely due to its positive outcomes from several studies published over the years. A study by Lin [16], published in PLoS, found that MDT increased quality of life adjusted years (QALYs) by 0.23 per person, when compared with non-MDT care. Cost-effectiveness of MDT has also been reported where MDT care leads to a reduction of $1931 annually per patient from reduced RRT and emergent need for dialysis since MDT was shown to slow eGFR decline and infection-specific hospitalisation [17].

Furthermore, a prospective study led by Chen [18] in Taiwan, also reported that patients under MDT care had a 51% reduced mortality than patients under usual non-MDT care. Moreover, a holistic approach provided via MDT care ensures that one will be guaranteed with an individualised and targeted management plan including health education and awareness of nephrotoxic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) which are contraindicated in CKD patients since they can lead to severe renal injury and progression of CKD [19].

Summary

To conclude, CKD is a chronic disease associated with multiple co-morbidities. To manage such a multi-faceted disease accordingly, only a multi-disciplinary team with professionals working towards the same goals and acting in the best interests of patients, will be able to improve patients’ quality of life and bring positive clinical outcomes. As CKD progresses, there is a need for a more collaborative effort between members of the MDT to address the increasing needs of the patients as they present with more complications. However, integration of such collaborative works may also need enhanced communication between colleagues to provide optimal care for the patients. Although effectiveness of providing a more integrated care via MDT has been established, determination of one optimal professional in an MDT has not been elucidated yet, requiring more randomised studies to follow [20-22].

References

- NHS England, Chronic kidney disease in England: the human and financial cost NHS England [pdf] (2017) London: NHS England Available.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice.

- Levey A S, Coresh J (2012) Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 379: 165-80.

- Neugarten J, Golestaneh L (2013) Gender and the prevalence and progression of renal disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 20(5): 390-395.

- Morton R L, Schlackow I, Mihaylova B, Staplin N D, Gray A, et al. (2016) The impact of social disadvantage in moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease: an equity-focused systemic review. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 31(1): 46-56.

- Vanholder R, Baurmeister U, Brunet P, Cohen G, Glorieux G, et al. (2008) A bench to bedside view of uremic toxins. J Am Soc Nephrol 19(5): 863-870.

- Kumar V, Abbas A K, Aster J C (2015) Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. In Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 9th ed, Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier Inc.

- (2014) National institute of health and care excellence (NICE), Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management [pdf] London: National institute of health and care excellence (NICE) Available.

- Di Angelantonio E, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, Gudnason V (2007) Renal function and risk of coronary heart disease in general populations: new prospective study and systematic review. PLoS Med 4(9): e270.

- Collins A J, Foley R N, Gilbertson D T, Chen S C (2015) United States renal data system public health surveillance of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl 5(1): 2-7.

- Keith D S, Nichols G A, Gullion C M, Brown J B, Smith D H (2004) Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organisation. Arch Intern Med 164(6): 659-663.

- Tomson C, Taylor D (2015) Management of chronic kidney disease Medicine 43(8): 454-461.

- Locatelli F, Pisoni R L, Combe C, Bommer J, Andreucci V E, et al. (2004) Anaemia in haemodialysis patients of five European countries: association with morbidity and mortality in the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns of study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 19(6): 1666.

- Webster A C, Nagler E V, Morton R L, Masson P (2017) Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 389: 1238-1252.

- Levey A S, Inker L A, Matsushita K, Greene T, Willis K, et al. (2014) GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 64(6): 821-835.

- Lin E, Chertow G M, Yan B, Malcolm E, Goldhaber Fiebert J D (2018) Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary care in mild to moderate chronic kidney disease in the United States: a modelling study. PLoS Med 15(3): e1002532.

- Chen P M, Lai T S, Chen P Y, Lai C F, Yang S Y, et al. (2015) Multidisciplinary care program for advanced chronic kidney disease: reduces renal replacement and medical costs. Am J Med 128(1): 68-76.

- Chen Y R, Yang Y, Wang S C, Chiu P F, Chou W Y, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for chronic kidney disease in Taiwan: a 3-year prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28(3): 671-682.

- Pazhayattil G S, Shirali A C (2014) Drug-induced impairment of renal function. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 7: 457-468.

- Cooper B A, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins J F, Craig J C, et al. (2010) A randomised, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 363: 609-619.

- Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) Kidney Int Suppl 7: 1-59.

- Public Health England, Department of Health, 2014 Chronic kidney disease prevalence model [pdf] London: Public Health England Available