Spermatocytic Seminoma Managed by Orchidectomy Only: A Case Report with a Long Term Follow Up

Youness Jabbour*1,3, Yassir Himmi1,3, Fouad Zouidia2,3, Tarik Karmouni1,3, Khalid Elkhader1,2, Abdellatif Koutani1,2 and Ahmed Ibn Attya Andaloussi1,2

1Urologie B departement - Ibn sina teaching hospital Rabat, Morocco

2Anatomical pathology department, Ibn Sina teaching hospital, Rabat, Morocco

3Faculty of medicine and pharmacy of Rabat, Morocco

Submission: July 15, 2018;Published: October 24, 2017

*Corresponding author: Youness Jabbour, Resident at Urology B department, Ibn Sina teaching hospital, Rabat, Morocco, Postal address: Hay El Menzeh N 800 C.Y.M 10150, Rabat, Morocco,

How to cite this article: Youness Jabbour, Yassir Himmi, Fouad Zouidia, Tarik Karmouni, et al. Spermatocytic Seminoma Managed by Orchidectomy Only: A Case Report with a Long Term Follow Up. JOJ uro & nephron. 2018; 6(2): 555682. DOI: 10.19080/JOJUN.2018.05.555682

Abstract

Spermatocytic Seminoma (SS) is a distinct testicular germ cell tumor, representing less than 1% of testicular cancers. The clinical features that distinguish spermatocytic seminoma from Classical Seminoma (CS) are an older age at presentation and a reduced propensity to metastasize. Currently, the management SS has changed to the increased use of surveillance, provided that there are no risk factors which may predict recurrence. Here, we report an additional case of spermatocytic seminoma and present a comprehensive relevant literature review concerning current clinical, histopathological, and therapeutic features.

Keywords: Orchidectomy;Spermatocytic seminoma; Classical seminoma

Abbreviations: SS: Spermatocytic Seminoma; CS: Classical Seminoma

Introduction

Spermatocytic Seminoma (SS) is a rare neoplasm representing 1 to 2% of germ cell tumors and 4 to 7% of all seminomas. It was first described by Masson in 1946 and rarely occurs before the fifth decade [1].Unlike Classical Seminoma (CS) originated from undifferentiated germ cells, SS may derive from spermatogonia and represented a more differentiated type of germ cell neoplasm.It presents as a solid palpable and painless mass of the testis with a slow clinical presentation, without elevation in serum markers or metastasis, and bears an excellent prognosis [2].Immunohistochemical staining can be extremely helpful to assess the diagnosis based on the negativity of all tested classic markers [3]. SS rarely metastasizes and since there is no documented benefit of radiotherapy or preventive chemotherapy and no adjuvant treatment is required after orchidectomy [2-4].

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old man presented complaining of gradually increasing right testicular painless swelling for 7 months. There was no history of cryptorchidism neither of bilateral scrotal pain, voiding complaints, local trauma, weight loss or hereditary disease. Physical examination revealed right testis enlargement with a firm consistency on palpation. Inguinal lymph nodes were not palpable.Scrotal ultrasonography revealed a well-defined 70 × 37 × 30 mm right testicular solid mass with heterogeneous echogenicity associated with a small hydrocele.The tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, and serum lactate dehydrogenase) were within normal limits.The patient underwent a large right radical inguinal orchiectomy. The specimen was 13,5 × 7,2 × 3,1 cm and weighed 183g. The mass had fleshy, pale-grey cut surfaces with invasion of the tunica.

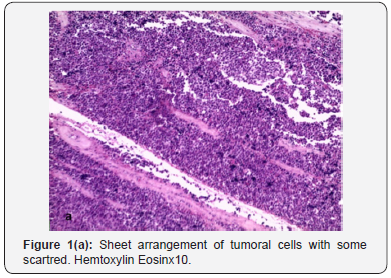

Microscopy finding was consistent with pure SS (Figures 1a & b) showing polymorphic cell proliferation, making sheets and scattered cells supported by fibrous stroma. We can distinguish within this germ component three types of tumor cells: small cells with dense and hyperchromatic nuclei surrounded by a thin cytoplasmic halo, intermediate-sized round cells with granular chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm and finally large cells with enlarged nuclei and filamentous chromatin.Post operatory was uneventful. Thoracic, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography performed 1 month after surgery was negative for lymphadenopathy or other metastases.The patient was followed-up closely without any adjuvant therapy and was in good condition with no evidence of metastasis 79 months after the operation.

Discussion

SS has been regarded as a malignancy along the lines of CS, but although the same clinical behavior, it exhibits different pathology and natural history. It is an uncommon tumor and, at our institution, represents less than 1% of all CS patients.SS is found exclusively in the testis and is not associated with any known risk factors for germ cell tumors including cryptorchidism, subfertility, or gonadal dysgenesis [4]. These tumors originate from a post-natal germ cell [1]. The detection of proteins SCP1 and XPA, which are normally expressed in the primary and pachytene spermatocyte stages, provide a clue that the origin of SS is in a more differentiated cell than in CS [5].Clinically, the main difference between spermatocytic and classical seminoma is the age of occurrence. SS tends to occur more commonly, in men aged over 50, while in CS, the age at diagnosis is between 25 and 40 years. The duration of symptoms was on the whole longer compared with CS, indicating a slower evolution and less malignant biological behavior.The size of the tumor was ranged from 10 to 16 cm with an average of 6.6 cm [6], usually replacing the whole testis.The spermatocytic variant is distinct from CS in its morphological characteristics with three different cell types (small, medium, large), spherical nuclei, eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm, lack of cytoplasmic glycogen, and sparse to absent lymphocytic infiltrate [7]. Other studies reporting different histogenesis of SS in comparison with CS are based on analysis of DNA ploidy and immunohistochemical profiles. While SS contains diploid to polyploidy cells as the principal finding, CS is predominantly aneuploid [8].

Differential features between SS and CS are presented in (Table 1).The malignant potential of SS is very low and only few cases of metastatic SS have been reported. The presence of an anaplastic component does not seem to impact the excellent prognosis of SS. Whereas the sarcomatous dedifferentiation was associated in the most reported cases with aggressive behavior and poor outcome. The sarcomatous component is usually rhabdomyosarcoma or undifferentiated, high-grade sarcoma and it appears that the metastatic disease develops usually from the sarcomatous elements [1].

The choice of therapy for an individual patient requires a consideration of the patient’s ability to comply with a surveillance regimen as well as acute and delayed complications of adjuvant chemotherapy or adjuvant radiotherapy. We generally suggest active surveillance for patients able to comply with an intensive follow-up schedule, because of the decreased risk of late complications and because of the ability to achieve the same overall cure rate when patients who relapse are treated appropriately.Primary tumor size greater than 4 cm and invasion of the rete testis have been identified as independent factors associated with an increased risk of relapse in multivariate analysis [9]. However, surveillance is not contraindicated in men with these features, provided the patient understands that the risk of relapse may exceed 30 percent and that they must adhere rigorously to the surveillance protocol. For patients with clinical stage I seminoma for which active surveillance is not appropriate and for those who want to minimize any risk of relapse, adjuvant chemotherapy with single agent carboplatin is suggested rather than radiotherapy. In all cases, there is no unanimity in the therapeutic procedure of SS. It was stated that SS is a radiosensitive tumor [10], but no direct evidence for this sensitivity was presented and the usefulness of postoperative radiotherapy was doubted. However, most reported patients in the literature with SS have received post-orchidectomy radiotherapy to the draining lymph node area.The main benefit of surveillance is that it avoids unnecessary treatment and the associated treatment related adverse effects.

Conclusion

Men with high risk for prostate cancer benefit from a diagnostic MRI. Prostate MRI decides which men to biopsy, defines the size and location of the suspicious nodule(s) to biopsy, predicts the grade of malignancy and locally stages the cancers. For prostate MRI to be accurate the exam has to be high quality imaging and interpreted by an experienced radiologist. Prostate MRIs are 90% accurate in diagnosing prostate cancer. Prostate cancers when diagnosed in their early stages with PSA and MRI can be treated and cured.

References

- Stueck AE, Grantmyre JE, Wood LA, Wang C, Merrimen J (2017) Spermatocytic Tumor with Sarcoma: A Rare Testicular Neoplasm. Int J Surg Pathol 25(6): 559-562.

- Chelly I, Mekni A, Gargouri MM, Bellil K, Zitouna M, et al. (2006) Spermatocytic seminoma with rhabdomyosarcomatous contigent. Prog Urol 16(2) : 218-220.

- Baldet P (2001) Tumeurs germinales du testicule, conceptions actuelles. Ann Pathol 21(5): 399-410.

- Hel Fellah, Tijami F, Jalil A (2008) Séminome spermatocytaire (à propos de deux cas). J Maroc Urol 11: 25-28.

- Rosai J, Silber I, Khodadoust K, Khodadou K (1969) Spermatocytic seminoma. Clinicopathologic study of six cases and review of the literature. Cancer 24(1): 92-102.

- Oosterhuis JW, Looijenga LH (2005) Testicular germ-cell tumours in a broader perspective. Nat Rev Cancer 5(3): 210-222.

- Burke AP, Mostofi FK (1993) Spermatocytic seminoma: a clinicopathololgic study of 79 cases. J Urol Pathol 1(6): 21-32.

- Eble JN (1994) Spermatocytic seminoma. Hum Pathol 25(10): 1035- 1042.

- Warde P, Specht L, Horwich A, Oliver T, Panzarella T, et al (2002) Prognostic factors for relapse in stage I seminoma managed by surveillance: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 20(22): 4448.

- Talerman A (1980) Spermatocytic seminoma. Clinicopathological study of 22 cases. Cancer 45(8): 2169-2176.