Management of Blunt Renal Trauma: An Experience from Tertiary Hospital

Poudyal S*, Chapagain S, Luitel BR, Chalise PR, Sharma UK and Gyawali PR

Department of Urology and Renal Transplant Surgery, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Nepal

Submission: May 30, 2018; Published: June 21, 2018;

*Corresponding author: Poudyal Sujeet, Department of Urology and Renal Transplant Surgery, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Nepal, Email: poudyal.sujeet@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Poudyal S, Chapagain S, Luitel BR, Chalise PR, Sharma UK. et al. Management of Blunt Renal Trauma: An Experience from Tertiary Hospital. JOJ uro & nephron. 2018; 5(5): 555671. DOI: 10.19080/JOJUN.2018.05.555671

Abstract

Background:Majority of hemodynamically stable patients with blunt renal trauma are successfully managed non operatively. The development of validated renal injury scoring system, improved critical care and interventional radiology has led to proper staging of injury severity and increased conservative management of blunt renal trauma.

Objective:To review our experience in management of blunt renal trauma.

Methods:A retrospective study of 34 patients was carried out in Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital from June 2015 to March 2017. All blunt renal injuries were graded according to American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) organ injury severity scale. The following data were collected: demographics, mechanism of injury, associated injuries, admission hemoglobin, blood transfusion, CT findings, renal injury grade, presence of other organ injuries on CT scan, type of management, indication for operative intervention, operative procedures, operative findings, any other interventions required, hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality.

Results: 34 renal injuries were identified. Majority of them had fall injuries (62.5%) followed by Road Traffic Accidents and assault. Two cases in pediatric age group had concomitant renal arterial thrombosis. Grade 4 renal injury was seen in 18 cases followed by Grade 2-3 in nine cases, grade 1 in two cases and grade 5 in three cases. Two grade 5 injuries needed exploration for hemodynamic unstability and underwent emergency nephrectomy otherwise all cases were managed successful nonoperatively. Three cases needed angioembolisation. There was no mortality due to blunt renal trauma.

Conclusion: Most renal injuries in hemodynamically stable patients can be managed conservatively. Angioembolisation is an effective treatment option in selective cases. Advancements in imaging techniques and improved critical care have favoured the conservative approach for even the severe grade of injuries.

Keywords: Angioembolisation; Blunt renal trauma; Injury severity scale; Renal arterial thrombosis

Abbreviation and Acronyms: AAST: American Association for the Surgery of Trauma; RTA: Road traffic Accidents; CT: Computed Tomogram; DTPA: Diethylene Triamine Pentaacetic Acid; PCN: Percutaneous Nephrostomy

Introduction

Blunt renal trauma are usually caused by high-energy collisions such as road traffic accidents (RTA), fall from a height and contact sports. They occur in 5 to 10 % of all trauma [1,2]. With current management, the majority of hemodynamically stable patients with blunt renal trauma are successfully managed nonoperatively [1,2]. The development of validated renal injury scoring system has led to improved staging of injury severity that is relatively easy to monitor. Injury Severity Scale for the kidney developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) in 1989 has been validated for clinical use and also predicts clinical outcome [3,4]. In addition, the improvement in trauma critical care has also led to increased conservative management of severe grade injuries [2,5,6]. We describe our experience of 34 blunt renal trauma cases in past 22 months.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of 34 patients admitted in Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital from June 2015 to March 2017. All blunt renal injuries except one, which was hemodynamically unstable at presentation, underwent contrast enhanced CT scan and were graded according to AAST organ injury severity scale. The following data were collected: demographics, mechanism of injury (RTA, fall, or other), associated injuries, admission hemoglobin, blood transfusion, CT findings, renal injury grade, presence of other organ injuries on CT scan, type of management, indication for operative intervention, operative procedures, operative findings, any other interventions required, hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality.

Results

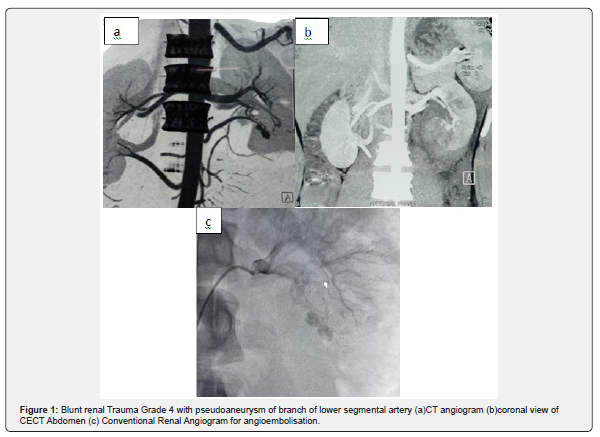

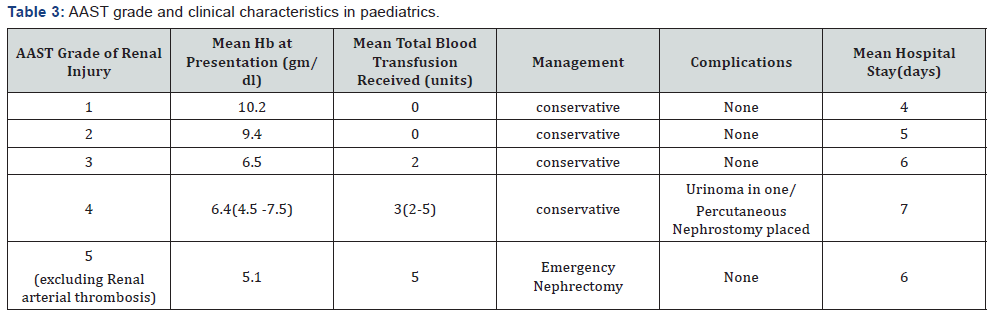

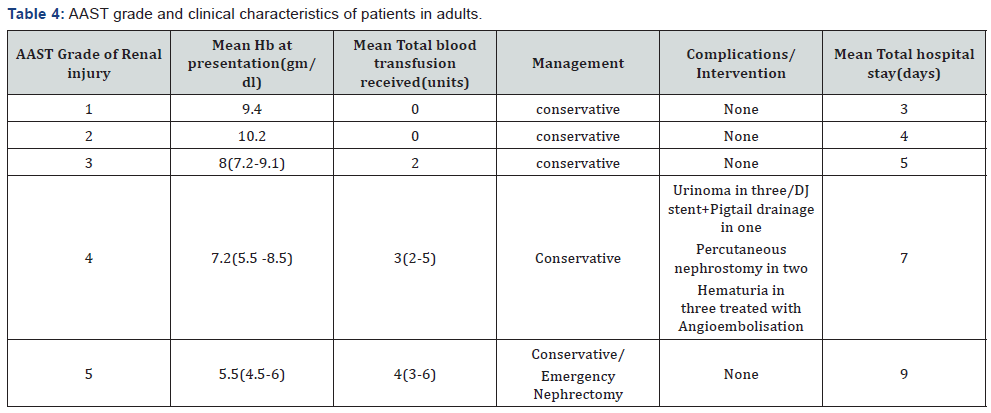

Thirty four renal injuries were identified. Demograhy of patients is depicted in Table 1. Majority of them had fall injuries (62.5%) followed by RTA and assault. Pediatric age group had more fall injuries (eight out of 13). Other injuries associated with renal injury were rib fractures in 13 cases, hemothorax in four, pulmonary contusions in two, splenic injuries in four cases, liver injuries in three cases and spine fractures in two cases. Rib fractures occurred in 11 cases mostly in adults. Two cases in pediatric age group had concomitant renal arterial thrombosis and managed conservatively. Table 2 shows the AAST grading of all the blunt renal trauma. Two grade 5 injuries needed exploration for hemodynamic unstability and underwent nephrectomy otherwise all cases were managed successful nonoperatively (Table 3 & 4). Three cases needed angioembolisation; one in acute stage for uncontrolled hematuria in 4th day and two others in 16th day and in 28th day for persistent hematuria due to pseudoaneurysm of lobar artery (Figure 1). Three cases needed percutaneous nephrostomy with one case needing pigtail drainage for urinoma and DJ stenting for concomitant renal pelvis injury. CT scan was repeated in 11 cases; most of them repeated for grade 4 and 5 injuries and in cases with persistent hematuria or collection suggestive of urinoma seen in USG abdomen. Blood transfusions were needed in 25 cases. All grade 4-5 renal injuries required blood transfusion with one third of patients requiring transfusion in grade 2-3 renal injuries. Grade 1 renal injuries did not require any blood transfusion. There was no mortality due to blunt renal trauma during admission in the hospital.

Discussion

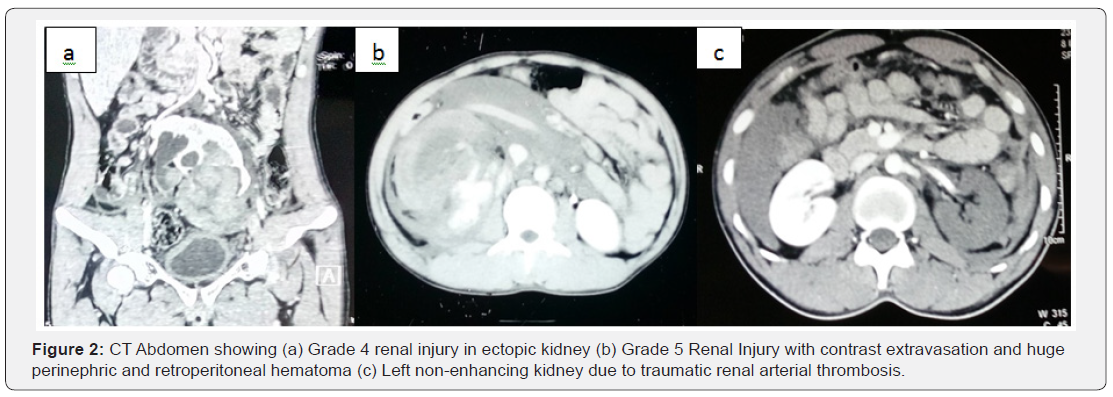

Majority of blunt renal trauma are managed conservatively [7,8]. The main focus in any renal trauma case is organ preservation while taking care of safety of the patient. As Nepal is an agricultural country, fall from cliff or tree while collecting fodder is a common cause of renal trauma in children as well as adults. Another cause of renal trauma is RTA, with majority being motorbike accidents and is mostly seen in young adults due to rash riding. Previous pathological kidney also makes the kidney susceptible to blunt trauma [9]. In this study, there were four hydronephrotic kidneys; the cause being congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction, ectopic pelvic kidney and the ureteropelvic junction stone (Figure 2). Three cases needed percutaneous nephrostomy drainage and all subsequently underwent elective nephrectomy after confirmation with DTPA renogram.

CT scan findings and AAST renal injury grading have changed the management paradigm of blunt renal trauma [3,4]. Higher grade determines the severity of injury and also predicts the type of management. These cases should undergo critical care monitoring for few days as they may need surgical exploration at any point of time. There are other CT findings like size of perirenal hematoma, intravascular contrast extravasation and medial renal laceration predicting early urgent intervention [10,11]. The increased number of Grade 4 injury in our series was due to the fact that only admitted cases were included. As our centre is a referral centre, less severe injuries are managed in other hospitals and only higher grade injuries are referred. In our cases, there was no contrast extravasation from main renal artery but many Grade 4 injuries had contrast extravasation from branches of segmental arteries. Of them, only one needed early angioembolisation for persistent hematuria. Size of perirenal hematoma was associated with number of blood transfusions but not with radiological or surgical intervention. The only parameter determining surgical exploration was hemodynamic unstability which was seen in two cases. Both were shattered kidneys with one had 5 mm rent in the junction between renal vein and IVC in addition. In cases of active extravasation of IV contrast, the decision of whether to undergo surgical exploration or angioembolization must be based on the presence of concomitant injuries, hemodynamic status of the patient and the experience of the surgical team and radiologists. The role of angiography and selective renal embolization in renal trauma is increasing and is an alternative treatment to laparotomy in patients who do not require immediate surgery [12,13]. Management of renal injuries did not differ in pediatric and adult age group [14,15]. All Grade 4 renal injuries, including one grade 5 shattered kidney were managed conservatively. With improved critical care, even Grade V injuries are managed nonoperatively in case of hemodynamic stability [16].

According to the study by Buckley and McAninch, the AAST renal injury grading system needed revision. Grade 4 should include all collecting system injuries, including ureteropelvic junction injury , segmental arterial and venous injuries and similarly, Grade 5 injuries, which before had included “shattered kidneys”, should also include renal hilar injuries (including thrombotic events) [17,18]. In this study, two children had traumatic renal arterial thrombosis (Figure 2). AAST grading has no special grade for such injury, so were not included in AAST grading system. According to Buckley and McAninch, this falls in Grade 5 renal injury. Similarly, one case had renal pelvis injury which was included in Grade 4 renal injury.

Repeat abdominal CT imaging with a delayed phase is recommended between 36 and 72 hours after initial injury for Grades 3 through 5 blunt renal injury [19]. In our study, not all Grade III-IV underwent repeat CT scan and CT was not repeated if patient’s condition is stable and there is no persistent or new onset hematuria or collection in USG abdomen. Malcolm et al reported that even Grade IV renovascular injuries can be followed clinically without routine follow-up imaging unless complicated by urine extravasation or persistent hematuria [20]. Urinoma occurs in 1% to 7% of all patients with renal trauma and resolves spontaneously in most cases [1]. Persistent urinoma requires intervention in the form of retrograde DJ stenting or Percutaneous Nephrostomy (PCN) [21,22]. In this study, urinoma occurred in four patients. One resolved with pigtail drainage only whereas three needed urinary diversion in the form of DJ stent or Percutaneous Nephrostomy (PCN) tube. Urinoma was more common with previous pathological kidney like hydronephrotic kidney with ureteropelvic obstruction. Delayed hemorrhage occurs in 13% to 25% of Grade 3 or 4 renal injuries that are managed expectantly and are mostly managed by embolization as done in two of our cases [23].

The retrospective design of this study may impart inherent limitations and biases. Long term follow up data of all the patients was not present. Therefore, long-term sequella of blunt renal trauma on renal function and hypertension could not be studied.

Conclusion

Most renal injuries in hemodynamically stable patients can be managed conservatively. Pathological kidneys should always be ruled out. Delayed complication like pseudoaneurysm and urinoma may necessitate stringent short term follow-up. Angioembolisation is an effective treatment option in selective cases. Advancements in imaging techniques and improved critical care have favoured the conservative approach for even the severe grade of injuries.

References

- Santucci RA, Wessells H, Bartsch G, Descotes J, Heyns CF, et al. (2004) Evaluation and management of renal injuries: consensus statement of the renal trauma subcommittee. BJU Int 93(7): 937-954.

- Broghammer JA, Fisher MB, Santucci RA (2007) Conservative management of renal trauma: a review. Urology 70(4): 623-629.

- Santucci RA, McAninch JW, Safir M, Mario LA, Service S, et al. (2001) Validation of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma organ injury severity scale for the kidney. J Trauma 50(2): 195-200.

- Shariat SF, Roehrborn CG, Karakiewics PI, Dhami G, Stage KH (2007) Evidence-based validation of the predictive value of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma kidney injury scale. J Trauma 62(4):933-939.

- Greer SE, Rhynhart KK, Gupta R, Corwin HL (2010) New development in massive transfusion in trauma. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 23(2): 246- 250.

- Van der Wilden GM, Velmahos GC, Joseph DK, Jacobs L, Debusk MG, et al. (2013) Successful Nonoperative Management of the Most Severe Blunt Renal Injuries. A Multicenter Study of the Research Consortium of New England Centers for Trauma. JAMA Surg 148(10): 924-931.

- Santucci RA, Fisher MB (2005) The literature increasingly supports expectant (conservative) management of renal trauma-a systematic review. J Trauma 59(2): 493-503.

- Moudouni SM, HadjSlimen M, Manunta A, Patard JJ, Guiraud PH, et al. (2001) Management of major blunt renal lacerations: is a nonoperative approach indicated? Eur Urol 40(4): 409-414.

- Schmidlin FR, Iselin CE, Naimi A, Rohner S, Borst F, et al. (1998) The higher injury risk of abnormal kidneys in blunt renal trauma. Scand J Urol Nephrol 32(6): 388-392.

- McGuire J, Bultitude MF, Davis P, Koukounaras J, Royce PL, et al. (2011) Predictors of outcome for blunt high grade renal injury treated with conservative intent. J Urol 185(1): 187-191.

- Dugi DD, Morey AF, Gupta A, Nuss GR, Sheu GL, et al. (2010) American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grade 4 renal injury substratification into grades 4a (low risk) and 4b (high risk). J Urol 183(2): 592-597.

- Mavili E, D¨onmez H, Ozcan N, Sipahioǧlu M, Demirtas A (2009) Transarterial embolization for renal arterial bleeding. Diagn Interv Radiol 15(2): 143-147.

- Hagiwara A, Sakaki S, Goto H, Takenega K, Fukushima H, et al. (2001) The role of interventional radiology in the management of blunt renal injury: a practical protocol. J Trauma 51(3): 526-531.

- Rogers CG, Knight V, MacUra KJ, Ziegfeld S, Paidas CN, et al. (2004) High-grade renal injuries in children--is conservative management possible? Urology 64(3): 574-579.

- Henderson CG, Sedberry-Ross S, Pickard R, Bulas DI, Duffy BJ, et al. (2007) Management of high grade renal trauma: 20-year experience at a pediatric level I trauma center. J Urol 178(1): 246-250.

- Altman AL, Haas C, Dinchman KH, Spirnak JP (2000) Selective nonoperative management of blunt grade 5 renal injury. J Urol 164(1): 27-30.

- Buckley JC, McAninch JW (2011) Revision of current American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Renal Injury grading system. J Trauma 70(1): 35-37.

- Chiron P, Hornez E, Boddaert G, Dusaud M, Bayoud Y, et al. (2016) Grade IV renal trauma management. A revision of the AAST renal injury grading scale is mandatory. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 42(2): 237-241.

- Davis P, Bultitude MF, Koukounaras K, Royce PL, Corcoran NM (2010) Assessing the usefulness of delayed imaging in routine follow up for renal trauma. J Urol 184(3): 973-977.

- Malcolm JB, Derweesh IH, Mehrazin R, DiBlasio CJ, Vance DD, et al. (2008) Nonoperative management of blunt renal trauma: is routine early follow-up imaging necessary? BMC Urol 8: 11.

- Titton RL, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Harisinghani MG, Arellano RS, et al. (2003) Urine leaks and urinomas: diagnosis and imaging guided intervention. Radiographics 23(5): 1133-1147

- Matthews LA, Smith EM, Spirnak JP (1997) Nonoperative treatment of major blunt renal lacerations with urinary extravasation. J Urol 157(6): 2056-2058.

- Lee DG, Lee SJ (2005) Delayed hemorrhage from a pseudoaneurysm after blunt renal trauma. Int J Uro 12(10): 909-911.